PHOTO-MATCHED TO GAME 3 OF THE 1932 WORLD SERIES, THE JERSEY COULD SET THE RECORD FOR MOST VALUABLE SPORTS COLLECTIBLE

By Robert Wilonsky

Babe Ruth’s fifth-inning home run against the Chicago Cubs during Game 3 of the 1932 World Series “has been argued about and debunked and reconsidered and investigated for almost a century,” Joe Posnanski wrote in 2023’s bestselling Why We Love Baseball. The Called Shot, as it’s been known ever since Babe’s swing met Cubs pitcher Charlie Root’s pitch that first day of October in Chicago – three little words about which endless stories have been told ever since.

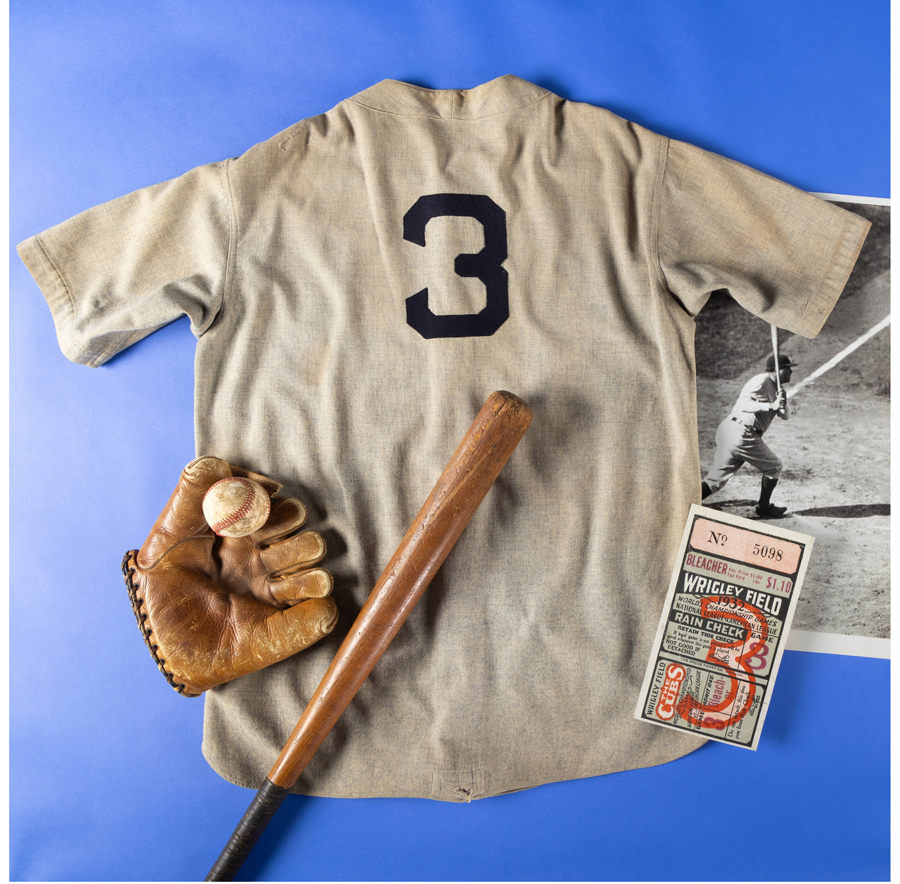

To that legend, Heritage Auctions offers another chapter: The New York Yankees road gray jersey Ruth wore that brilliantly bright Saturday in Chicago will be a centerpiece of the Summer Platinum Night Sports Auction from August 23-25. The jersey, bearing Ruth’s No. 3, has been photo-matched to Game 3 of the 1932 World Series.

The jersey Babe Ruth was wearing when he made his infamous ‘Called Shot’ during Game 3 of the 1932 World Series will be the centerpiece offering in Heritage’s August 23-25 Summer Platinum Night Sports Auction.

The jersey is twice authenticated, including by MeiGray Authenticated, which says the jersey was matched using two photos from Getty Images and a third from The Chicago Daily News showing Ruth, Lou Gehrig and manager Joe McCarthy in the dugout. Ruth gifted the jersey to a Florida man following a round of golf, where it remained until the man’s daughter auctioned it nearly two decades ago. It has only recently been photo-matched.

“Ruth’s World Series jersey is the most significant piece of American sports memorabilia to be offered at auction in decades,” says Chris Ivy, Director of Sports Auctions at Heritage. “Given its history, its mythology, we expect that when the final bid is placed, it will hold the record as the most expensive sports collectible ever to cross the auction block.”

For now, at least, that record belongs to another Yankees legend, Mickey Mantle, whose 1952 Topps card graded Mint+ 9.5 by Sportscard Guaranty Corporation sold for $12.6 million at Heritage in August 2022.

Ruth’s World Series jersey is the most significant piece of American sports memorabilia to be offered at auction in decades. Given its history, its mythology, we expect that when the final bid is placed, it will hold the record as the most expensive sports collectible ever to cross the auction block.”

–Chris Ivy, Director of Sports Auctions

History doesn’t often talk about the fact Ruth hit two home runs in that World Series skirmish, the first coming in the initial frame – after Ruth, with a two-ball count, taunted Root by demanding he throw him strikes. Cubs fans and players were already giving Ruth hell as lemons flew from the stands and insults streamed from the dugout. Ruth homered to right center with the next pitch.

“The boos for Ruth as he rounded the bases were loud and even ominous,” Posnanski writes. “Ruth luxuriated in them. That’s not the Called Shot. Not yet.”

That moment in the fifth inning when Ruth gestured toward something or someone – perhaps the Chicago Cubs’ dugout or Root or the center field flagpole – has been endlessly celebrated, imitated and replicated over the past 92 years. That home run, which came on a two-strike count, has been depicted in paintings, exaggerated in movies and parroted by anyone who’s ever played beer-league ball on a rec-league field. Those three little words will live so long as there’s someone left to tell stories about the day Ruth smashed a baseball farther than anyone had ever before hit a baseball at Wrigley Field.

As Posnanski points out, Ruth had called a few shots before, including once as a promise to a young man in a hospital and once as a response to jeering Cubs fans in the 1918 World Series, when Ruth was still throwing baseballs for Boston. The man hit 714 home runs during his 22 seasons in the sun. Most would inevitably wind up as footnotes in a historic career. Some have great stories. But only one is the final World Series home run of his career and the stuff of which myth was made.

In his 1948 book ‘The Babe Ruth Story,’ Ruth recounts that fateful fifth-inning home run: ‘That ball just went on and on and on and hit far up in the center-field bleachers in exactly the spot I had pointed to.”

Some significant witnesses were sitting in the Wrigley Field stands on October 1, 1932, among them Franklin Delano Roosevelt, the New York governor days away from winning the White House, and future Supreme Court Justice John Paul Stevens, then just a boy of 12. But they were just spectators. Others would step forward over the coming days and decades to tell a story that grew into folklore.

By all accounts, it took but a few hours before a journalist began crafting the myth. Joe Williams, then a sports editor for Scripps-Howard, recapped the moment for the evening papers: “In the fifth,” he wrote, “with the Cubs riding him unmercifully from the bench, Ruth pointed to center field and punched a screaming liner to a spot where no ball had been hit before.” As the National Baseball Hall of Fame notes, Williams added to his wire story a headline invoking a billiards reference: “Ruth Calls Shot As He Puts Home Run No. 2 In Side Pocket,” which is how the story appeared in the New York World-Telegram.

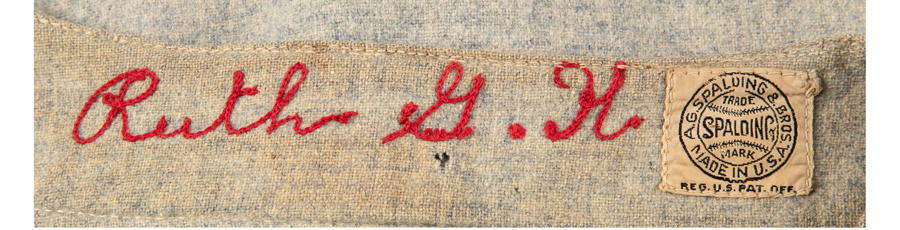

Ruth’s name is stitched in red inside the jersey’s collar.

“Interestingly, in the ensuing days, other writers began following his lead and started reporting that the Babe had called his shot,’’ Michael Gibbons, director emeritus and historian of the Babe Ruth Birthplace & Museum in Baltimore, once told the Hall of Fame. “It kind of spread like wildfire after that.”

At first, Ruth didn’t have much to say on the subject, except that it must be true if it’s in the newspapers. But five days later, Gehrig went on a national radio show to talk about his “favorite topic, a gent named George Herman Ruth.” Gehrig got to the story when it was still fresh and encased it in amber.

“He stands up there and tells the world he’s going to sock that next one – and not only that, but he tells the world right where he’s gonna sock it, into the center field stands,” Gehrig said. “He called his shot and then made it. I ask you, what can you do with a guy like that?”

MeiGray Authenticated photo-matched the jersey to two photos from Getty Images and a third from ‘The Chicago Daily News.’

It also didn’t take long for Ruth to embrace the tale, no matter how tall it might have grown. By 1948’s The Babe Ruth Story (a collaboration with journalist Bob Considine), the legend had become fact, as far as Ruth was concerned. He wrote that he was so irked by the razzing that he’d pointed toward the center field bleachers even before Root had thrown his first pitch, much less his ill-fated third.

“I guess the smart thing for Charlie to have done on his third pitch would have been to waste one,” Ruth said in his book. “But he didn’t, and for that I’ve sometimes thanked God. While he was making up his mind to pitch to me I stepped back again and pointed my finger at those bleachers, which only caused the mob to howl that much more at me. Root threw me a fast ball. If I had let it go, it would have been called a strike. But this was it. I swung from the ground with everything I had and as I hit the ball every muscle in my system, every sense I had, told me that I had never hit a better one, that as long as I lived nothing would ever feel as good as this.

SUMMER PLATINUM NIGHT SPORTS AUCTION 50072

August 23-25, 2024

Online: HA.com/50072

INQUIRIES

Chris Ivy

214.409.1319

CIvy@HA.com

“I didn’t have to look. But I did. That ball just went on and on and on and hit far up in the center-field bleachers in exactly the spot I had pointed to.”

On the next page, Ruth would call that home run “the most famous one I ever hit.”

The Yankees won that game 7-5 and swept the Cubs out of the Series the next day.

For decades, the only “proof” anyone could offer that Ruth called his shot were some radio re-creations, big-screen fictions and painted fantasies. It took decades for film to surface showing the home run, by which point the story had taken root as the sequoia of baseball legends: Either you believed Ruth was gesturing toward the Cubs’ dugout (said Mantle, years later, “Well, I think he called it”) or motioning toward the bleachers (“I don’t see a called shot here,” said Yankees great Reggie Jackson). There was no in-between.

But this is certain: This was Ruth’s jersey that day in that place during that at-bat. And it calls its shot at the auction block in August only at Heritage.

ROBERT WILONSKY is a staff writer at Intelligent Collector.

ROBERT WILONSKY is a staff writer at Intelligent Collector.