THE LEGENDARY SCREENWRITER’S INCONCEIVABLE ESTATE INCLUDES SCRIPTS, AWARDS AND A ‘PRINCESS BRIDE’ SIGN WORTH A TRIP THROUGH THE FIRE SWAMP

By Robert Wilonsky

Screenwriting Star and Hollywood Skeptic.”

EVENT

RARE BOOKS SIGNATURE® AUCTION 6241

Dec. 9-10, 2021

Online: HA.com/6241

INQUIRIES

James Gannon

214.409.1609

JamesG@HA.com

That was how The New York Times headlined its obituary for William Goldman upon the two-time Oscar-winner’s death in November 2018 at the age of 87. Which seemed a rather gentle way of saying he adored and abhorred in equal measure the very thing that made him famous: the movie business, or, as he called it, “the screen trade.” He was revered, adored and acclaimed not only for his novels and screenplays, which were plentiful and popular, but for his disdain for the industry that treats writers more like annoyances than indispensables.

“Nobody knows anything,” Goldman famously wrote in 1983’s Adventures in the Screen Trade. Except William Goldman.

“He always had a love-hate relationship with the movie business,” says his daughter Jenny, a writer herself. “To the point where he never wanted to move to Los Angeles or live in L.A., and he didn’t. That’s pretty unusual, too, to have the career that he had in screenwriting and not had to make the move to L.A. to make that happen. Everybody does the ‘I’m going to want to be a screenwriter. I’m moving to Hollywood.’ He never did that.”

Goldman did, however, become among the most famous screenwriters of the latter half of the 20th century, and certainly one of its most celebrated. He collected two Academy Awards for his screenplays – one for Best Original Screenplay for 1969’s Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid; another for Best Adapted Screenplay for 1976’s retelling of Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein’s All the President’s Men. And he counted among his filmography such works as The Princess Bride, Marathon Man and Magic – each based on a novel he’d written.

Goldman’s screenplays and novels and essays were as readable as a dear old friend’s handwritten note; you could easily devour his work as swiftly as he produced it. “The world’s greatest and most famous living screenwriter,” critic Joe Queenan called Goldman in a 2009 profile – self-effacing, too, and never “a show-off,” Queenan wrote.

Perhaps that’s because he had awards and rewards enough to let others do the heavy lifting for him. But of this, there is no doubt: There was no writer more fearless, reliable, tenacious and talented working in the business of show during the 1960s and ’70s than Bill Goldman.

“My father … was a combination of egocentric and humble,” Jenny says, essentially summarizing the split personalities of most writers. “There was a part of him that was very proud of what he achieved, and there was another part of him that always thought it was shaky ground. He was a successful writer who earned his living writing, which is still a fairly exceptional thing.”

Heritage Auctions is proud to offer on Dec. 10 more than 40 items from the estate of William Goldman, including typescript copies of screenplays and novels housed in custom clamshells kept on the shelves of his Manhattan home – among them, his copies of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid’s final script, a revised final draft for The Princess Bride and the first draft of his beloved A Bridge Too Far adaptation.

Heritage’s Dec. 9-10 Books Signature® Auction also features the infamous “pre-rehearsal version” of the All the President’s Men screenplay dated March 1975 – the so-called “ROSS MACDONALD VERSION,” Goldman wrote in the script’s introduction, “Watergate looked at primarily as a mystery.” This, perhaps, is the version of the screenplay studied and debated – and, by the acolytes, adored – more than any other, as it came amidst so much unwelcome tinkering and interference by Woodward, Bernstein and Robert Redford.

Here, too, are posters from several of his stage and screen productions, as well as an enlarged and framed copy of The Princess Bride’s 1977 paperback cover; a signed and hilariously inscribed There’s Something About Mary poster from filmmaking brothers Bobby and Peter Farrelly after he complimented the comedy in The Los Angeles Times; and two books, Dreamcatcher and Hearts in Atlantis, signed and inscribed by Goldman’s self-proclaimed No. 1 fan Stephen King to his buddy Bill.

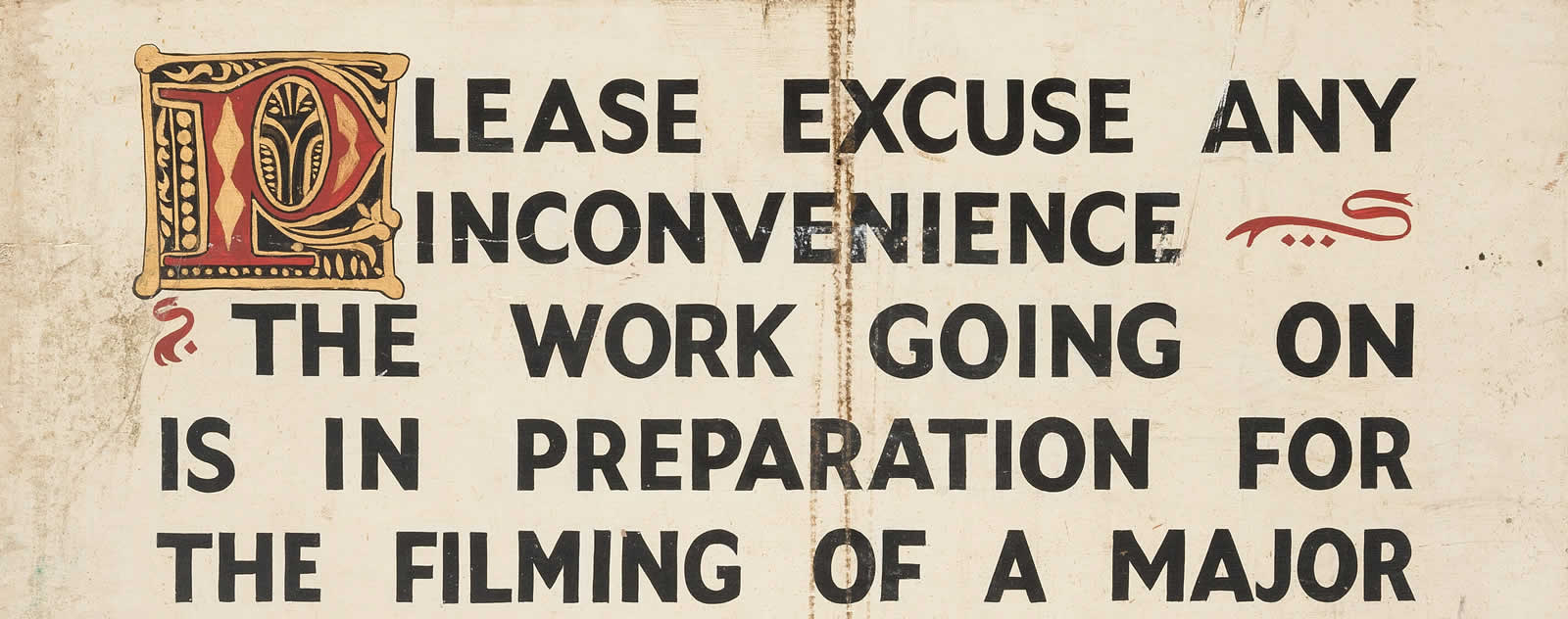

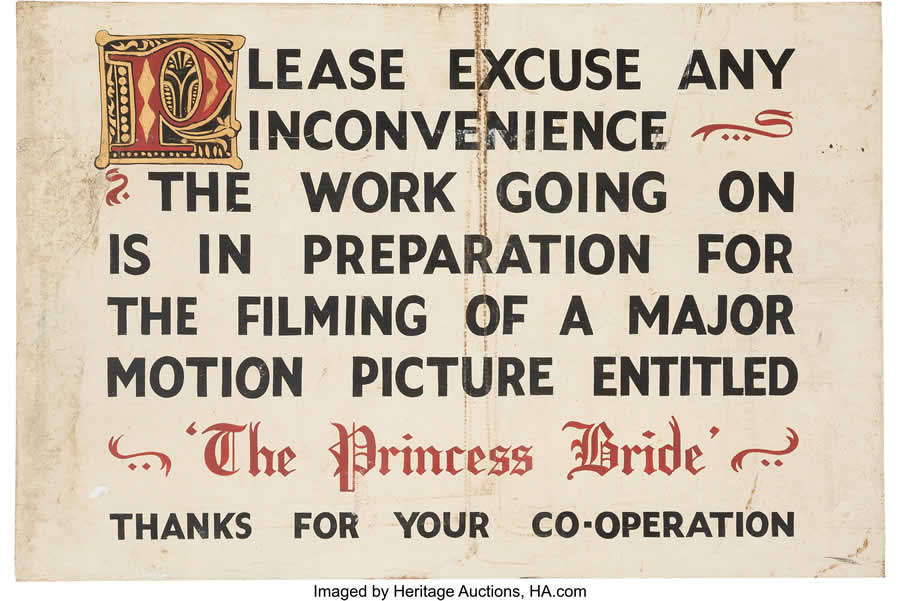

An oversized wooden, hand-painted sign from the set of The Princess Bride may well prove the most coveted item from the Goldman collection, as it hints at the magic to come: “Please excuse any inconvenience,” it reads. “The work going on is in preparation for the filming of a Major Motion Picture entitled The Princess Bride. Thanks for your co-operation.” To imagine the making of The Princess Bride was an inconvenience is, well, inconceivable.

“There was a group of people when I went to Oberlin College who were reading Princess Bride aloud – and this was before the movie, well before the movie,” Jenny says. “They were Princess Bride nerds and they found out that I was William Goldman’s daughter, and every day when I would walk into the south hall to go get my salami sandwich for lunch, they would say, ‘Oh, we’re up to the Fire Swamp.’ They would always tell me where they were in the reading of the book, and it was very sweet.”

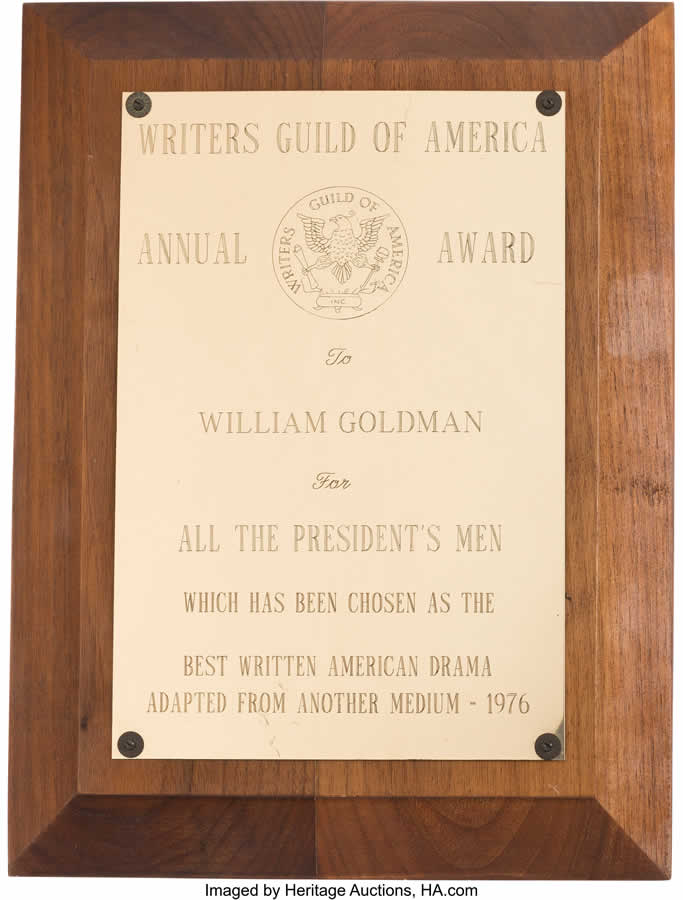

Here, too, are his brass plaques from the Writers Guild of America – one for Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, chosen in 1969 as the Best Written American Drama written directly for the screen; another for All the President’s Men, honored as the Best Written American Drama adapted from another medium. This auction also includes the Laurel Award for Screen Writing Achievement given to Goldman in 1985 by the WGA.

It was one thing to be honored by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, as Goldman was twice – though he only showed up to pick up his Oscar once, for All the President’s Men. But he’d been a member of the Writers Guild since 1965, and though he often quoted Groucho Marx’s line about not wanting to belong to any club that would have him as a member, being feted by others who toiled on the blank page meant something more to him than just another nod.

“I think as a writer, you have total control when you’re actually writing it, whatever it is, even if it’s a short story or a novel,” Jenny says. “You have total control until you give it to your editor or you give it to the director. And if you’re a control freak, which I think most writers actually probably are deep down, then maybe you’re not going to like what they say or like the edits they want to make or the cuts or the casting changes. … I think that’s the tightrope you walk between being willing to collaborate, being brave enough to collaborate and then accepting what the outcome of that might be.”

This auction also features the writer’s tools: five typewriters used throughout Goldman’s career, from the circa-1960s Hermes Baby Typewriter to an Olympia International SM9 Model dating from the 1970s. One doesn’t buy Goldman’s typewriter expecting to write like the master, just as one does not pick up Miles Davis’ trumpet expecting to suddenly play “So What.” But there is inspiration in those keys – not to mention years’ worth of great writing from a man who made one of the hardest tasks in the world look so easy. Each typewriter still bears a tag from the repair shop to which it was once sent: “For William Goldman,” a few of them read, which might intimidate even the heartiest soul.

“He had several going because they would break,” Jenny says. “You’d have to have one in the shop, because they weren’t reliable. My father was a very fast typist. In fact, that’s what he did in the military. He worked at the Pentagon when he was in the Army as a typist. So, he was a good typist, and he didn’t even really want to switch over to electric because electric typewriters are much more sensitive than manual, so, kicking and screaming, he was brought into the late 20th century into the 21st century. What he did actually was go straight from typewriter to a Mac.”

A late addition to this auction might be the most personal item in it: a well-worn Italian leather chair and matching ottoman in which visitors to Goldman’s home would often find themselves on the receiving end of writing lessons. Jenny recalls this was the chair occupied by famous names just escaping their anonymity – the likes of Tony Gilroy, Scott Frank, David Koepp, collaborator Mike Lupica and Aaron Sorkin, who told Nobody Knows Anything (except William Goldman) director Caroline Case that he “taught me everything I know and about a 10th of what he knows.”

The chair is certainly not much to look at; it’s even a little tacky to the touch. But it’s like any pile of bricks eventually declared a landmark: The significance isn’t the chair itself, but who owned it and who sat there and what happened there and why.

“I was not aware until after my dad’s service that Scott and Tony called that ‘The Supplicant’s Chair,’ which I found out much later,” Jenny says. “I just called it the chair I sat in in the living room. But, that’s what it was jokingly known as by some of the people who worked with him. He loved mentoring writers. It was actually one of his fondest things.

“When we had his memorial service, we had it at the Ziegfeld Theater in New York, and we had a marquee [that] had his picture on it, and a lot of people showed up and a lot of people flew in from California and other places. And I said when I gave my speech that he would have been amazed at the people who turned out, and I believe that’s true. There are many people who were huge fans of his, and on some level he knew that, but there was a part of him that always pushed that aside, that didn’t want to let that interfere or take away from whatever his drive was. But I believe he did not know how many lives he touched. I really believe that.”

ROBERT WILONSKY is a staff writer at Intelligent Collector.

ROBERT WILONSKY is a staff writer at Intelligent Collector.

![William Goldman. Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. [Los Angeles] Twentieth Century-Fox Film Co., July 15, 1968](https://intelligentcollector.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/William-Goldman.-Butch-Cassidy-and-the-Sundance-Kid.-Los-Angeles-Twentieth-Century-Fox-Film-Co.-July-15-1968.jpg)

![[William Goldman]. Hermes Baby Typewriter. Circa 1960s](https://intelligentcollector.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/William-Goldman.-Hermes-Baby-Typewriter.-Circa-1960s.jpg)