NOT EVEN LEGENDARY COMIC BOOK ARTIST FRANK MILLER COULD SAVE THE PINT-SIZE HERO AND HIS SHORT-LIVED SERIES, BUT HE SURE HAD FUN TRYING

By Robert Wilonsky

I’ve been trying to reach Bob Rozakis since, give or take, the summer of 1977. We finally spoke two weeks ago when I called his Long Island, New York, home.

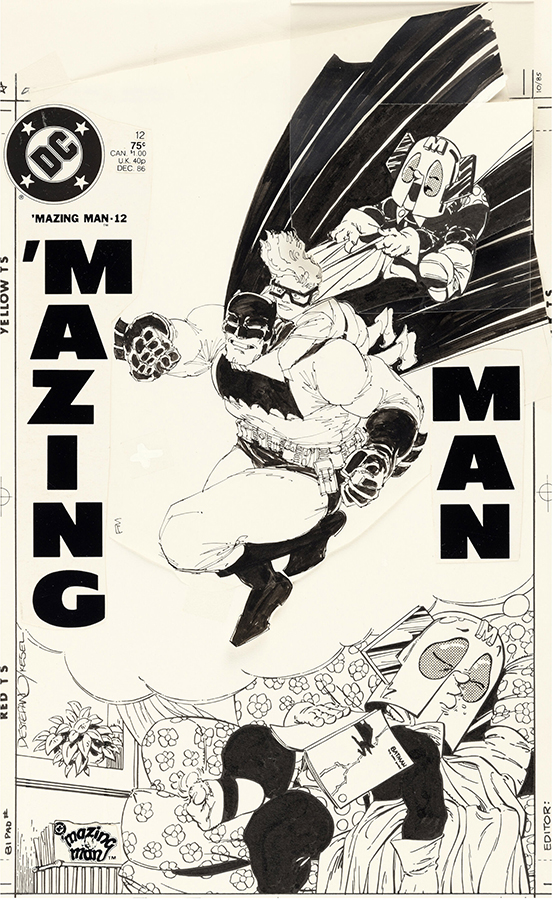

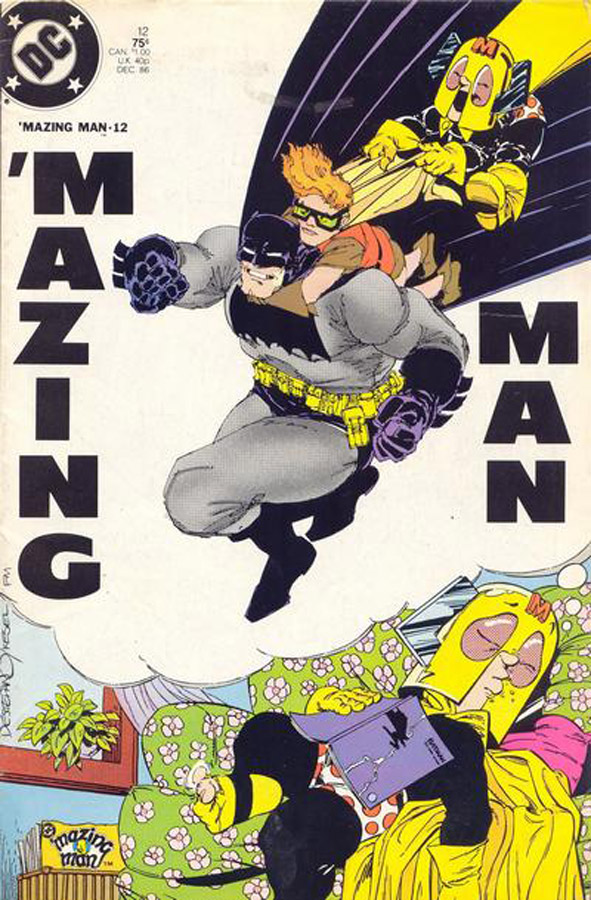

I rang Rozakis to discuss his creation ’Mazing Man, a 3-foot-tall hero (sort of) who had a 12-issue run at DC Comics in the mid-1980s. The book culminated in a finale whose cover was partially drawn by Frank Miller and heads to auction this month for the first time. There’s a pretty good backstory behind that famous, beloved 1986 cover featuring Miller’s bulked-up Dark Knight and his Robin, Carrie Kelley, which appeared only a few months following Batman: The Dark Knight Returns’ industry-redefining run.

Frank Miller, Stephen DeStefano and Karl Kesel’s ‘’Mazing Man’ No. 12 cover original art (DC, 1986). Available in Heritage’s January 9-12 Comics & Comic Art Signature® Auction.

But first, because he’s a kind and patient man, Rozakis wanted to know what I wanted to ask him 47 years ago.

Because, you see, in the late 1970s, Rozakis was as much the public face of DC Comics as Superman and Batman. He ran the letters page for its official “fanzine,” The Amazing World of DC Comics, which debuted in the summer of 1974 and now sells for small fortunes. Two years later, in May 1976, Rozakis was proofing pages in the production department when he told then-president Sol Harrison that “it would be nice to have a page telling readers what was coming out next week.”

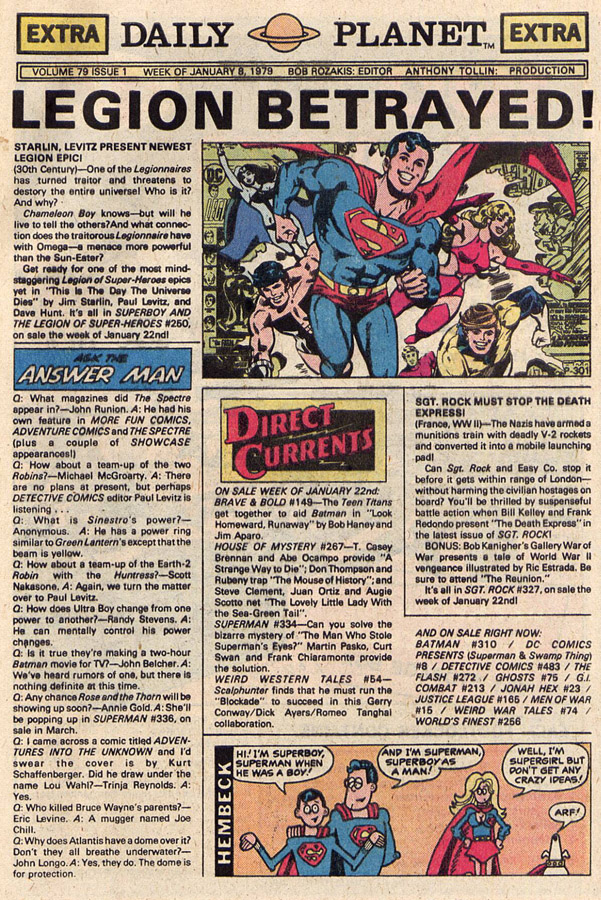

As a result, Rozakis created the Daily Planet page, which ran in the back of every DC comic. Soon after that, he began responding to inquiries from readers, which is how Rozakis became known as DC’s Answer Man.

“Once I started printing the names of the letter-writers, the piles of mail I got was more than anyone else at DC was getting,” says Rozakis, who teaches a comic book history course at Farmingdale State College. “So that just grew into the whole thing where everyone just wanted to get their name in the comic books.”

I remember this well. When I was 9 or 10, I sent maybe a dozen letters to The Answer Man, which I relayed to Rozakis during our interview in early December. He wanted to know if he’d ever answered my myriad queries. When I told him no, he asked if I could remember one. Sadly, sort of: When did Green Arrow grow a goatee, and why didn’t everyone recognize him as Oliver Queen?

“He grew it when Neal Adams took him over in 1969’s The Brave and the Bold No. 85,” Rozakis said. To which he didn’t need to add the obvious at this late date: No one recognized him because, you know, it’s a comic book and not real life.

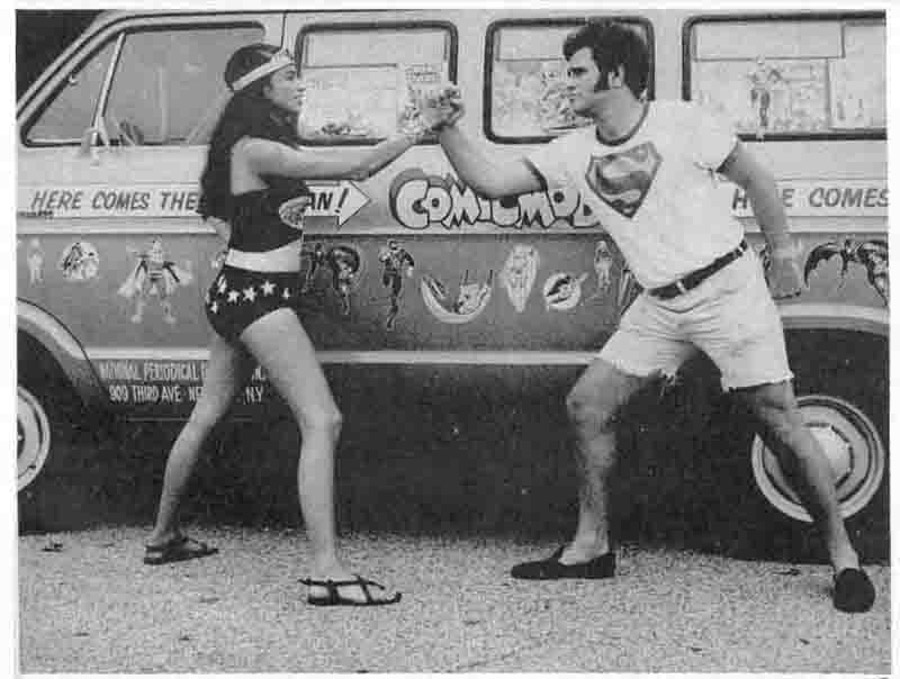

In addition to creating ’Mazing Man, Bob Rozakis created DC Comics’ ‘Daily Planet’ page, where he responded to reader questions as The Answer Man.

This brings us back to ’Mazing Man’s origin story and, later, how he teamed up with The Dark Knight, at least for the cover of his final issue.

In addition to his tenure as The Answer Man and, later, DC’s production manager, Rozakis was among the company’s most prolific writers, beginning with a backup story in Detective Comics No. 445 in the spring of 1975. That’s where most of his stories wound up, behind the centerpiece tales in issues of Action Comics, The Flash and Batman Family, including a well-regarded Marshall Rogers and Michael Golden-drawn storyline that recast Man-Bat as a “doting husband with a pregnant wife who turned to bounty hunting to pay the bills,” as Keith Dallas and John Wells wrote in Comic Book Implosion: An Oral History of DC Comics Circa 1978.

During his tenure at DC, Rozakis wrote Teen Titans (during which he created Duela Dent, the Joker’s daughter), Freedom Fighters, The Secret Society of Super Villains, DC Comics Presents, Superman: The Secret Years (for which Frank Miller provided the covers), Weird War Tales and other titles that flew off the spinner racks. He even wrote some of the Hostess ads illustrated by DC’s finest. Rozakis was both superstar and utility player, and by the time his tenure at DC wrapped, he’d written something for nearly every super-somebody and nobody the company had ever published.

“The only thing I never got to write was Justice League of America, and that was the one I always wanted to do. The closest I got was the DC Super-Stars baseball game,” he says. “And I loved doing it. I always looked at these characters as hopeful. I always looked at Superman as: ‘I have these powers, and it’s my job to help these people.’ Occasionally I find myself as part of the Superman vs. Batman debate. People ask, ‘Well, why do you like Superman better?’ Because he’s the hero. Batman is angry. He wants to beat up people. Superman says, ‘I want to help you.’”

The cover of ‘’Mazing Man’ No. 12 as it appeared on spinner racks in 1986

But by the mid-1980s, things began to change: The Dark Knight Returns and Alan Moore’s Watchmen transformed how comics were written, drawn, read and interpreted, for better or worse. Watchmen was hailed as the moment comic books “grew up” and “became literature”; The Dark Knight Returns provided Batman (if not the entire comics industry) with what critic Elvis Mitchell called “a savage rebirth.”

“That’s when the Bronze Age ended and the Dark Age, as I call it, began,” Rozakis says. “By which I mean bad things started to happen to characters. We kill Superman and break Batman’s back and have Green Lantern go crazy and kill the entire Green Lantern Corps and kill Barry Allen’s Flash and Supergirl.”

Rozakis had a front seat to the revolution: He was DC’s production manager in 1986, and his name appears – listed fifth! – among DC Comics Inc.’s higher-ups inside The Dark Knight Returns.

But as comics turned darker, Rozakis and colleague Stephen DeStefano sought something brighter. And so their ’Mazing Man was born, starring a pint-size character named Siegfried Horatio Hunch III, who “always dressed in a homemade superhero costume complete with a yellow cape, metal helmet that covered his entire head, and polka-dot boxers worn over his black tights,” as writer Alan Irvine described him in 2022.

“He lived in Queens with his best friend Denton Fixx, who happens to have a head like a dog, Denton’s half-sister K.P., and a collection of eccentric friends and neighbors,” Irvine wrote in his lengthy appreciation of “’Mazing Man: The Hero You Never Knew.” “If you think all this sounds like an unlikely set-up for a superhero comic, you’re right. DeStephano [sic] and Rozakis were always clear that ’Mazing Man existed in our universe, not in the DC Universe of Batman and Superman.”

Says his creator now, ’Mazing Man was intended “as something lighthearted but at the same time aimed at a more mature audience. There were adult themes, like one character considering having an affair with the guy in the office, but it was always intended as something hopeful and kind – a situation comic meant to be bright and based in reality. This happens in people’s lives: They get married, have jobs and things happen. But at the same time, there’s also funny stuff that happens in people’s lives, and we poked fun at the comics, too.”

’Mazing Man didn’t look or read like a mainstream comic book, which is probably why it didn’t sell well – and why it’s not remembered or appreciated today, to the point where my favorite comic shop doesn’t stock a single back issue. It was funny, smart, wry, meta, snarky and charming. As Irvine wrote two years ago, 1986 “was just not the time for a sweet, whimsical comedy to find an audience.”

Rozakis (right) in his DC Comics days

By the summer of ’86, it was clear the diminutive Maze, as he was called, was on his last legs. So Rozakis called his old pal Frank Miller to see if his Dark Knight could lend a hand to save a fellow hero from cancelation.

“I told Frank we would bill it as the missing piece of his Dark Knight collection,” Rozakis says. Which is how Miller and DeStefano wound up collaborating on this cover, which features Maze fast asleep with a copy of The Dark Knight Returns No. 1 in his hand while his head is filled with a grinning, gargantuan Batman, Carrie with her arms around his neck and Maze clinging to Robin’s cape.

In the end, ’Mazing Man No. 12 was the final issue, though the character returned in a few specials and an episode of The Brave and the Bold. Years later, Comic Book Resources would refer to the series as “a refreshing change of pace.”

“Frank thought it was a fun idea,” Rozakis says. “I don’t remember whether it was Stephen who came up with the idea of ’Mazing Man dreaming the image or if Frank came up with it. But somewhere along the way, Frank did his Batman and Robin, and Stephen and Karl Kesel did the rest. It was just so much fun seeing these two worlds collide, even for a moment.”

ROBERT WILONSKY is a staff writer at Intelligent Collector.

ROBERT WILONSKY is a staff writer at Intelligent Collector.