IN THE EARLY 1970S, ANDY WARHOL MARKED HIS RETURN TO PAINTING WITH ONE OF HIS MOST RECOGNIZABLE SERIES OF IMAGES

By Blake Gopnik

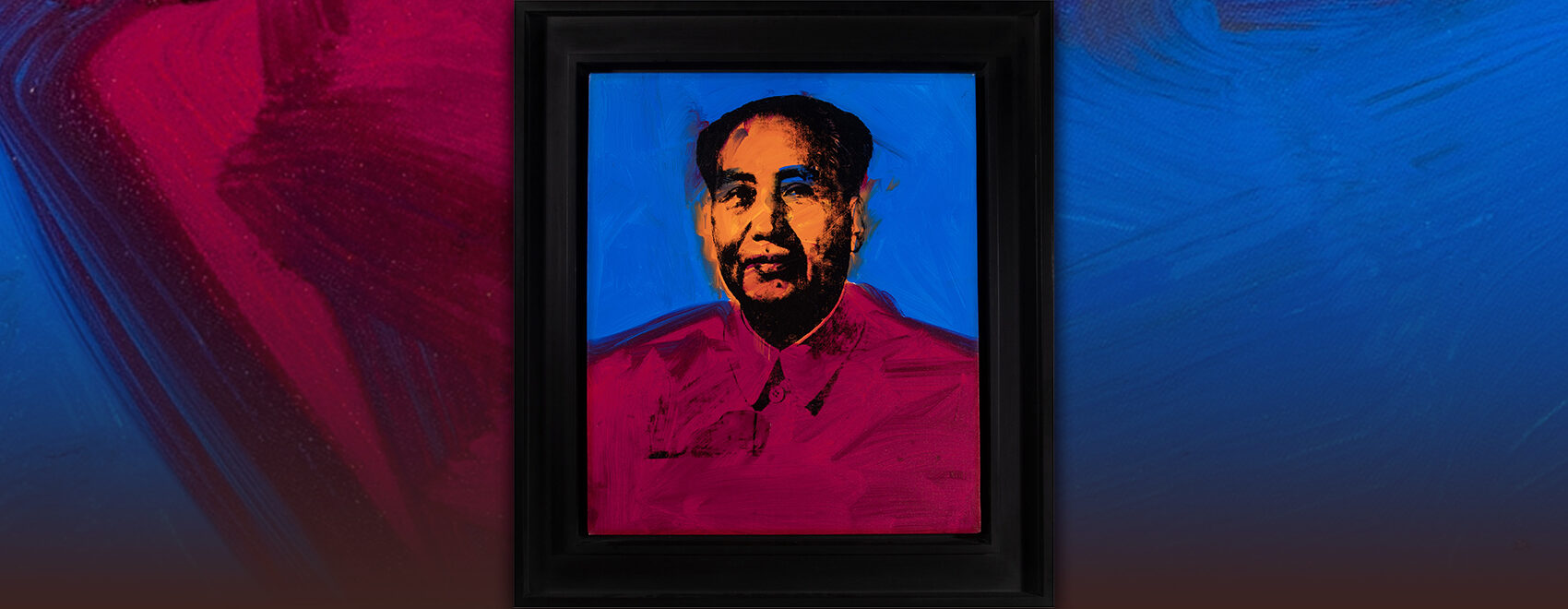

Editor’s note: On December 10, during its Modern & Contemporary Art Signature® Auction, Heritage will present Andy Warhol’s iconic 1973 painting ‘Mao.’ This example of Warhol’s portrait of Mao Tse-tung is one of the most desirable from the late artist’s portrait series of China’s Chairman. The painting also comes with outstanding provenance, having once belonged to acclaimed interior designer and longtime Warhol partner Jed Johnson. In advance of the auction, we asked art critic and Warhol historian Blake Gopnik to share his thoughts on the masterwork and Warhol’s iconic ‘Mao’ series.

When Andy Warhol began his Chairman Mao project, early in 1972, it represented his first notable body of images in almost a decade. His last major series had come into view back in November of 1964, when he’d shown his Flowers with Leo Castelli and then announced that he’d given up painting for film.

In 1972, Warhol was still hurting from the assassin’s bullet that had (briefly) killed him in June of 1968. Since he still had a studio to fund, it’s tempting to see his Maos as taking an easy, marketable step back toward the Pop Art that had first made him famous. His Mao works might be just more riffs on cultural superstars, taking off from the Marilyns and Jackies and Elvises of the early 1960s. The Maos are that, of course – the Chairman was certainly an international celebrity, with a face at least as well-known as any actor’s – but they also bear important witness to Warhol’s deep engagement with the particular artistic moment he was in.

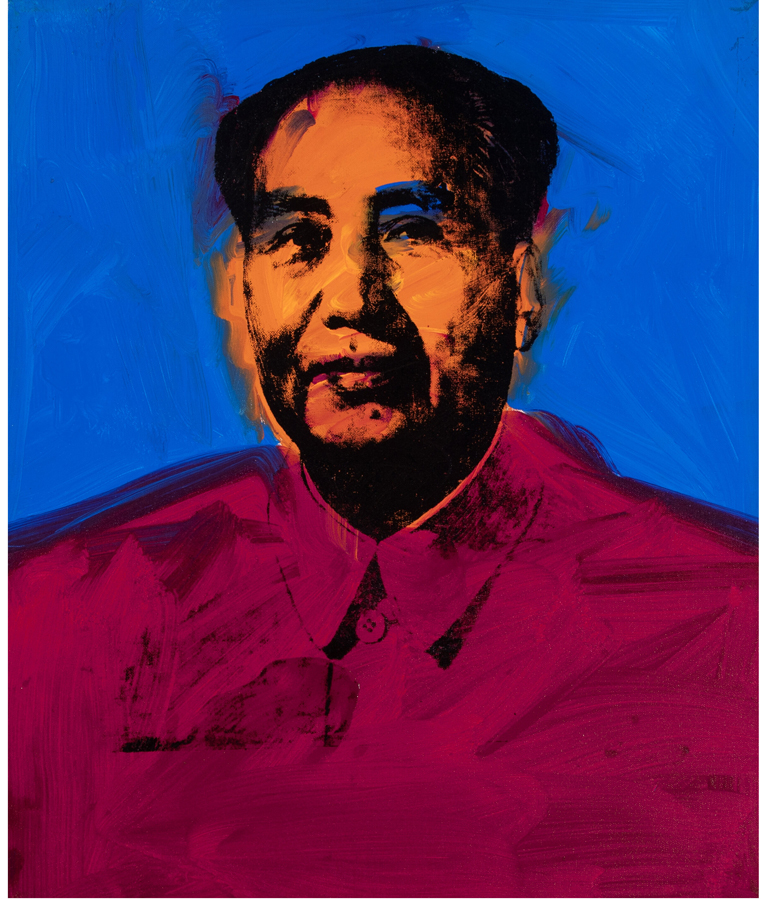

The ‘Mao’ painting available at Heritage is awash in Warhol’s canny use of blue, burgundy, ochre and black, and it is arguably the most visually enticing of the entire series of 16 original paintings of Mao he created at this size.

A quarter century earlier, in art school, Warhol’s teachers had taught him to have an invested belief in that classic modernist mantra, “Make it new.” He never abandoned that ideal. In 1972, his Maos represented his latest attempt at living it.

The Maos came at a moment when the Color Field abstraction of Kenneth Noland and Helen Frankenthaler still held sway among most supporters of what passed for “advanced” art, as we have now mostly forgotten. Warhol’s new series clearly engaged with that tradition. The Mao in this auction plays with the tensions between “fields” of brilliant blue, orange and red, while in other works in the series Warhol limits himself to intense complementary contrasts (yellow with purple; red with green) or goes for pastel shades instead. In their thick brushwork, the paintings also echo the surface effects that were so important to Jules Olitski and Larry Poons, the latest art stars of that era who used the new acrylic medium, also there in Warhol’s Maos, to turn their canvases into relief maps of paint.

Ignore the face that repeats across the Maos, and they could pass as studies in the formalist fundamentals of shape, color and surface that preoccupied so many of the most influential critics of Warhol’s century.

But even as Warhol was successfully engaging with the latest abstraction, he was opening up an ironic distance from it. Rather than advocating for the virtues of purely formal experimentation, the Maos come closer to proclaiming it moribund, at a moment when, out on the furthest cutting edge of the art world, the recent declarations of the Death of Painting were read less as diagnoses than as obituaries. All those different versions of Mao could be seen to imply that the differences among them might be more random than willed. Warhol’s words support that view. He called his frantic brushwork “hand jobs” and “abstract pseudo-painting,” saying he could do it “without even thinking.” He compared the colorful painting he did on his Maos to cooking. A video of him at work on a wall-sized Mao makes that comparison seem almost too fancy: He looks more like a janitor mopping a floor.

Warhol’s Maos might count as his signature on a note of condolence to painting.

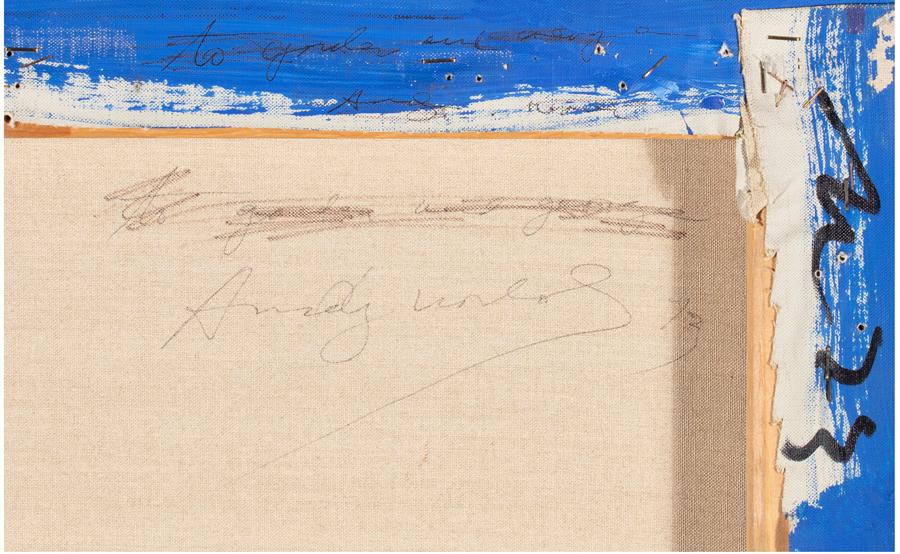

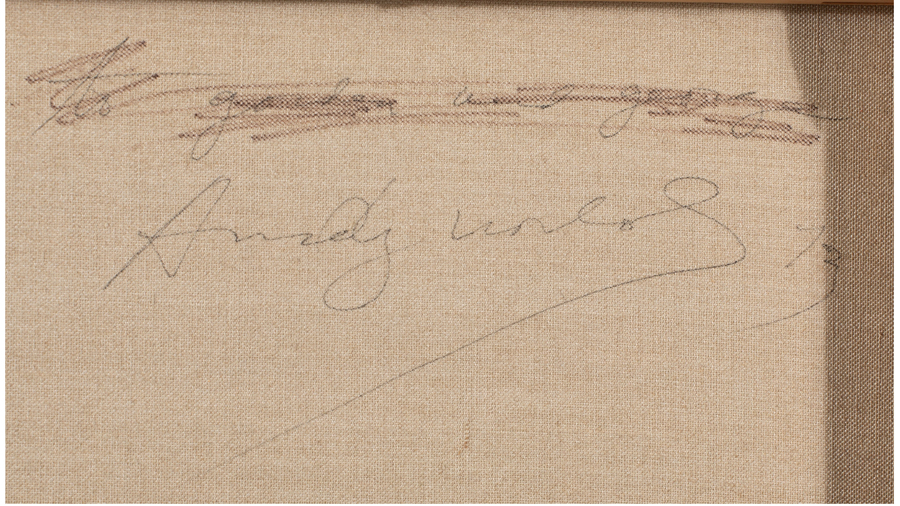

Warhol initially inscribed the piece ‘To Gordon and George,’ presumed to be Gordon Locksley and George Shea of Locksley Shea Gallery, then crossed off their names. The painting ultimately went to Jed Johnson, who met Warhol in 1968. Jed’s brother Jay Johnson inherited the work, and it later became part of the important Ammann collection from which it was acquired by Heritage’s consignor.

The first hint we have of Warhol’s interest in Mao comes in a phone call, in September of 1971, where he talked about artmaking among the Chinese: “They don’t believe in creativity. The only picture they ever have is of Mao Tse-tung. It’s great. It looks like a silkscreen. It’s the only picture they ever have of him – they don’t believe in people being creative.” That “great” of Warhol’s sounds like it signals hearty agreement with an abandonment of the “creative.” A ceaseless repetition of the same found image, printed over randomly mopped-on paint, might be a marker of the uncreative – but it’s important to note that the massive project that results bills non-creativity as the next place for creative fine art to head.

“Art isn’t now,” Warhol said, the same year the art of his Maos came to be. What counted as properly “now,” for many of the era’s most committed avant-gardists, was a deep commitment to politics. In 1969, members of the Art Workers’ Coalition had organized the “Moratorium of Art to End the War in Vietnam.” The next year, they paraded their potent And Babies poster in front of Picasso’s Guernica. In ’71, Hans Haacke earned headlines when his exposé of a slum landlord’s holdings got his solo show at the Guggenheim canceled.

Warhol had taken politics to heart at least since art school, when he’d signed a petition supporting Henry Wallace, a politician on the far-left flank of the New Deal. In the spring of 1962, almost 15 years later, the first time a work of Warhol’s Pop Art got broad exposure he was still toying with explicit social critique. He said his new work was “a statement of the symbols of the harsh, impersonal products and brash materialistic objects on which America is built today.” But that was pretty much the last time Warhol wore his politics on his sleeve. (In private talk, and in his donations, he was always a dedicated progressive.) With the Mao project, however, politics – if not Warhol’s, then someone’s – were inescapably present in the more than 2,700 images Warhol churned out of the ruler of one quarter of the world’s population.

Decades into the 21st century, with China’s dedication to capitalism so clearly on view, it’s hard for us to realize how alive Maoism still was, as a real political option, when Warhol chose the subject of his new project. The New York Times spared space for a political scientist’s essay on whether Maoism – the “war of the underdeveloped peasant world against the advanced capitalist nations” – would survive its 77-year-old founder. Maoist guerillas around the world fought under the assumption that it would. I remember hearing my parents talk about the dedicated Maoists who taught alongside them at our local university, and who were never without their khaki caps with red stars.

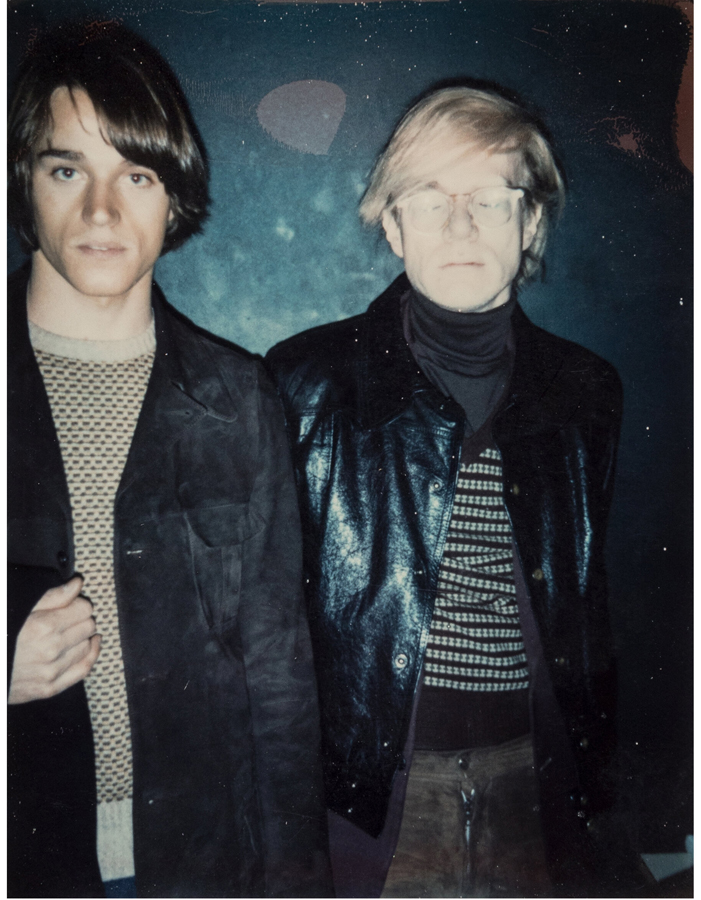

This snapshot of Jed Johnson and Andy Warhol was taken by Warhol’s assistant Fred Hughes in February 1971, a year before the artist began his ‘Mao’ series. The Polaroid print was sold in a May 2023 Heritage auction.

That same fall of ’71 when Warhol was first talking about Mao, Emile de Antonio, the Marxist documentarian who had been one of Warhol’s most ardent fans at the start of his Pop career, said, “If I have to make a choice between American painting and the attempt to turn men’s minds and the search for a collective soul, then I’m more interested in what Mao is doing than in the art of my friends.”

You might say that, in the project that followed by his friend Warhol, a similar claim was being made – but it’s indeed a claim of “interest,” rather than a commitment for or against what Mao and his image might stand for.

Warhol’s mature works had always been built around what a philosopher might call “pure ostension”: Just pointing at something in the world, where the pointing itself (“Look at this!”), rather than any critical comment or aesthetic embellishment, was the fundamental purpose. Ostension had always been sitting there at the very heart of picture making, but Warhol was possibly the first artist to use his work to point at that pointing.

With his Mao series, his pointing at pointing reached its apotheosis: His Maos were pointing at an image that, for all its political potency – because of its political potency – was itself all and only about ostension. Like Byzantine icons and any number of earlier, often magical images, the pictures of Mao that proliferated across communist China achieved almost all their aims by simply bringing the Great Leader into view, without any need to editorialize beyond that. They were selling a steak that required no sizzle.

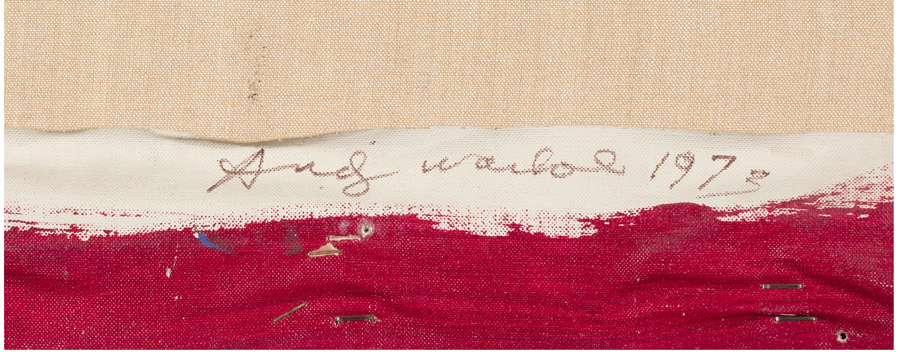

This ‘Mao’ painting, which is signed twice, holds a special place in Warhol’s and Pop Art’s history. Heritage’s December 10 event marks the first time the work will cross the auction block.

The Campbell’s soup can had been specially designed to appeal. The same could be said for Marilyn and even Jackie Kennedy. Warhol’s ostension toward those cultural icons also captured their visual and social features and made us respond to them. With Mao, however, there was nothing about the look of his image that spoke to who he was or what he meant: His image was just an ever-present stand-in for the man himself – a way to “make the absent present,” in the classic Renaissance formula for how the new realism was supposed to work.

This is what Warhol’s Maos may mostly be about.

“Make it new” may have been Warhol’s mantra, but, with his training in classical modernism, the “it” that mattered most to him was art itself. His works rarely did much to renew their subjects: A soup can remained a can of soup; a communist leader remained most distinctly himself. Instead, in the very act of depicting Mao, Warhol made his art new by digging deep into images at their most basic and showing us just how they work.

BLAKE GOPNIK is the author of Warhol, the first comprehensive biography of the Pop artist, published by Ecco in 2020. He is also a regular contributor to The New York Times.