LOPEZ ESCAPED POVERTY TO BECOME A HOLLYWOOD LEGEND WITH INTERNATIONAL HIT ‘IF I HAD A HAMMER,’ AND APPEARANCE IN 1967 WAR FILM ‘THE DIRTY DOZEN’

By Robert Wilonsky • Photographs by Mark Davidson

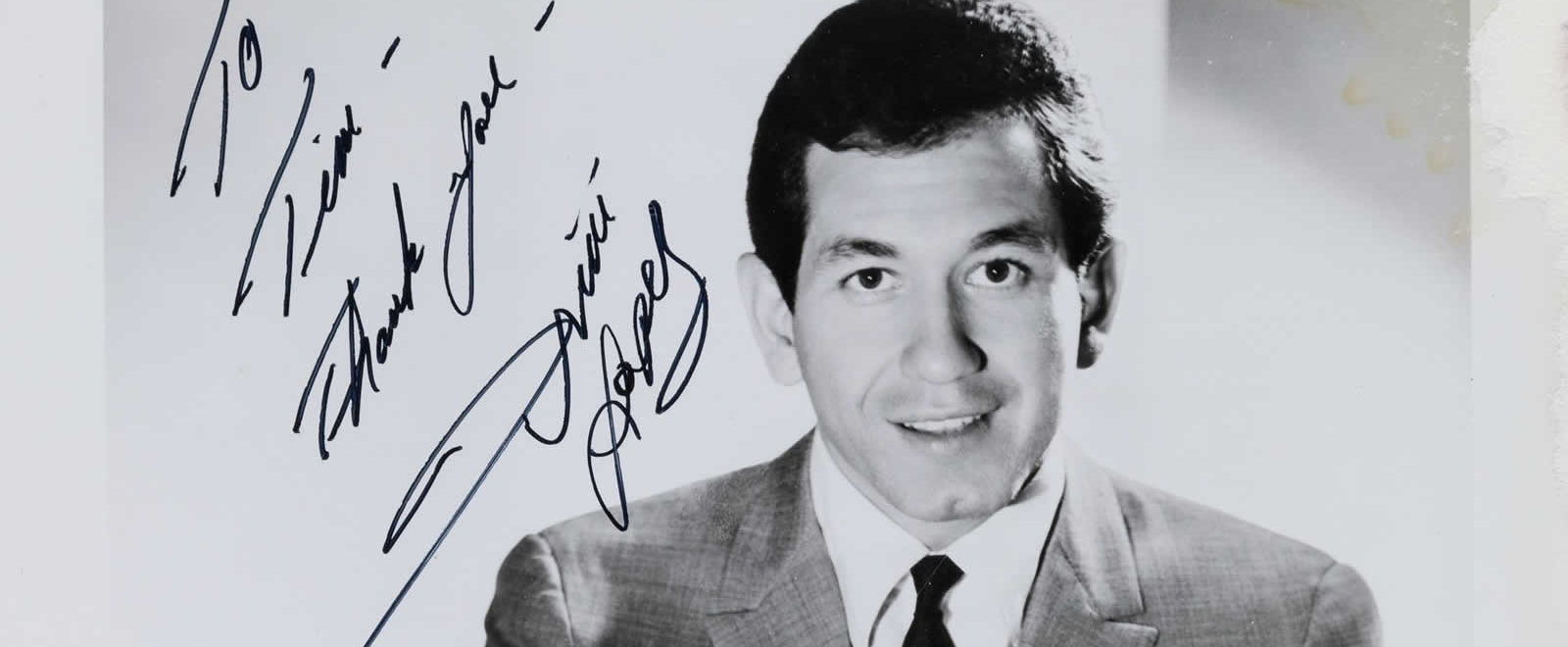

Trini Lopez first appeared in the pages of his hometown newspaper on Feb. 13, 1953, his name listed among those scheduled to perform at the fourth anniversary celebration for the Spanish Club of Dallas. At the time, Trinidad Lopez III was 15 years old, a student about to drop out of Crozier Technical High School. He was not yet a protégée of Buddy Holly and Frank Sinatra, a topper of pop charts, a friend of the Beatles and Elvis Presley, a performer on The Ed Sullivan Show, a guest on What’s My Line?, on the cover of Time, or a member of The Dirty Dozen.

EVENT

►ENTERTAINMENT & MUSIC MEMORABILIA SIGNATURE® AUCTION 7238

May 1-2, 2021

Online: HA.com/7238a

INQUIRIES

Carolyn Mani

214.409.1677

CarolynM@HA.com

►TRINI LOPEZ PALM SPRINGS MODERNIST ESTATE AUCTION 20027

April 13, 2021

Online: HA.com/PalmSprings

INQUIRIES

Nate Schar

214.409.1457

NateS@HA.com

In time, his stardom afforded him a home in Palm Springs, Calif., where he lived for decades and filled the sunbaked space with a lifetime of memories – all of which, including photos, guitars, costumes, awards and annotated movie scripts, are coming to Heritage Auctions’ May 1-2 Entertainment & Music Memorabilia auction. Even Lopez’s beloved home is scheduled to be offered by Heritage on April 13.

ROCK HITS FROM FOLK SONGS

In the early 1950s, Trini Lopez was just a kid living on a street called Alamo in a part of Dallas called Little Mexico, “a black and Mexican ghetto,” he told me years later, where “the Mexicans were killing the blacks and the blacks were killing the Mexicans.” Lopez liked to tell stories about where he came from, to talk about how all of his neighborhood pals “ended up dead from shotgun wounds or ended up in prison,” if only to underscore the extraordinariness of his journey from barrio to Palm Springs, his ascension from hellraiser to hero.

Enlarge

Lopez sang everything. Made rock hits of folk songs. Endured cruelty. Designed a guitar still favored by modern rockers. Befriended legends only to become one himself.

And so it’s little wonder that when he died in August 2020 at the age of 83 from complications related to COVID-19, his passing garnered worldwide headlines, from Rolling Stone to the BBC to his hometown Dallas Morning News. The New York Times’ headline honored Lopez as a “Singing Star Who Mixed Musical Styles.”

No less than Foo Fighters frontman Dave Grohl took to Twitter to honor Lopez’s “beautiful musical legacy.” He wrote, too, that the son of Little Mexico “unknowingly helped shape the sound of the Foo Fighters from day one,” courtesy the red 1967 Trini Lopez signature guitar Grohl has played on every one of the band’s albums.

Enlarge

“I was always amazed by his mind,” says his nephew Trini Martinez, formerly drummer in the acclaimed, influential band Bedhead. “There are so many songs he could just perform. He had perfect pitch, and got bored really quick. He wasn’t afraid to change it up. And then he developed his own sound with more rhythm – the Trini Beat is what they called it. He dug into it. That’s the best way I can put it. He owned it. My uncle wasn’t afraid to rock, and he rocked the way he wanted to. People knew early he was going to be someone.”

As early as 9 years old, in fact, when young Trini occasionally accompanied his sister Lucy on stage at St. Ann’s Catholic School in Little Mexico. But the family would often leave Texas for long spells to pick tomatoes for 16 hours a day in faraway states. On the long drives the boy taught himself to play guitar, when his hands weren’t sore from the work.

Enlarge

As Lopez liked to tell it, his father, who had been a singer, actor and dancer from Moroleón, Mexico, bought 12-year-old Trini a $12 pawn-shop guitar to keep the boy out of trouble. It was a black acoustic made by Gibson, the very company for which Lopez would famously design electric guitars, in standard and deluxe models, in the early 1960s. In countless ways, that Gibson changed his life.

“All of my friends were mad at me, ’cause I wouldn’t go running around with them all over the place,” Lopez said when we spoke 15 years ago. “I was practicing at home ’cause I fell in love with the guitar right away. I fell in love with music right away, so thank God that I did that.”

SLOW CLIMB TO FAME

By the time he was 15, when his name first appeared in The Dallas Morning News, Lopez was listening to and falling in love with Little Richard, B.B. King, Clarence “Gatemouth” Brown, Fats Domino and, of course, Elvis Presley, one day to become Lopez’s nearby neighbor in Palm Springs. “I knew that if I just played Mexican music,” Lopez once said, “I wasn’t going to go anywhere.”

Enlarge

He dropped out of Crozier Tech to help support the family, and spent the next decade making the long, slow climb to fame. He performed on local-TV dance-party shows, played benefits and fundraisers, and got gigs at Dallas nightclubs and hotel ballrooms. His nephew Robert Diaz recalls the family going to see his uncle’s combo play at shopping-center ribbon-cuttings around Dallas.

“Mother would get teary-eyed, and Dad would stamp his foot to the beat, so happy for his brother-in-law,” Diaz says. “He would wink at us as he sang. We all got into the music. My heart throbbed. He had us all in the palm of his hands. It was just an exciting time.”

But Lopez’s success was anything but guaranteed in a city where black and brown were, and remain, segregated and strangled by the redline of racism – “and we were just Mexicans,” Diaz says, “or at least that’s how people identified us.”

Among them was Buddy Holly’s legendary producer Norman Petty, who, at Holly’s insistence, invited Lopez and his all-White combo to record at his studio in Clovis, N.M., for Columbia Records. The way Lopez and his family tell the story, Petty pulled aside the members of the band, then called the Big Beats, and convinced them they should sing, not Lopez.

“They all conspired against me,” Lopez once told interviewer Gary James. “The guys were all jealous of me anyway ’cause the girls used to like me very much. They didn’t let me sing, so we did nothing but instrumentals. I couldn’t believe it. I cried myself to sleep for two weeks while we were recording.”

Enlarge

The Big Beats released only one single, “Clark’s Expedition/Big Boy,” in 1957. In later years, Lopez often described Petty as a “redneck.” Lopez wound up breaking up the band after driving the members back to Dallas, as though he were their chauffeur.

Enlarge

“That broke his heart,” Diaz says.

Lopez got his very first solo recording deal in 1958, with Dallas-based Volk Record Company. And despite the hometown acclaim beginning to pile up in The Dallas Morning News, which chronicled his every doing, the label’s owner asked him to change the Lopez to something else. Of course, he refused.

“I was proud of my heritage, always will be,” Lopez once recounted during an interview for Gibson guitars. Upon the occasion of his 80th birthday, Lopez told The Dallas Morning News, “I’m proud to be a Mexicano.”

“The Right to Rock/Just Once More” was his sole Volk release.

Enlarge

The next year he signed to legendary King Records out of Ohio, the one-time home of hillbilly music that eventually turned its ear toward R&B and a nascent sound called rock ’n’ roll. Lopez recorded about a dozen singles for King, among them a cover of the 1940s country hit “Don’t Let Your Sweet Love Die” that went to No. 1 in his hometown, but nothing hit big. Only years later, after he became a chart-topper on Frank Sinatra’s label, did King push his cuts on two full-length records that eventually became collectors’ items.

In 1960, he briefly flirted with becoming Buddy Holly’s replacement as the Crickets’ frontman; there were even stories in the paper about how students at Crozier Tech were “glowing with pride” over the move. But Lopez passed; later he would say it was because the Crickets were living high off royalty checks and “weren’t in a hurry to get going.” And he was. Lopez had paid his dues. No more waiting.

By 1961, he was living in Los Angeles, with a regular stint at Ye Little Club in Beverly Hills and, later, the jazz and rock club P.J.’s on Santa Monica Boulevard. Singer Nino Tempo was so enamored of Lopez he brought composer and arranger Don Costa to see him one night; Costa became such a fan he introduced Lopez to his boss, Frank Sinatra, who caught the act and had Lopez signed to his upstart Reprise Records.

PART OF POP VERNACULAR

The kid from Little Mexico by 1963 was a worldwide sensation thanks to a record called Trini Lopez at PJ’s, his first official record – the one with “If I Had a Hammer,” which topped the charts in more than three dozen countries, and his clap-along covers of Ritchie Valens’ “La Bamba” and “America” from West Side Story. The live album, which still swings harder than Mickey Mantle, sold more than 1 million copies.

Enlarge

By January 1964, Lopez was playing in Paris with some tousled up-and-comers from England billed as Les Beatles. For three remarkable weeks, Lopez, French chanteuse Sylvie Vartan, Paul McCartney, John Lennon, George Harrison and Ringo Starr shared a bill and the stage at the Olympia Theatre, a legendary stint documented in fab photos republished endlessly upon Lopez’s death in the summer of 2020.

From then on, Lopez was part of the American pop vernacular – music phenom, a television regular, guitar designer, magazine cover material, movie star, ubiquitous, adored. Some knew him as the singer of “Lemon Tree”; others, as the soldier killed off far too early in director Robert Aldrich’s 1967 film The Dirty Dozen.

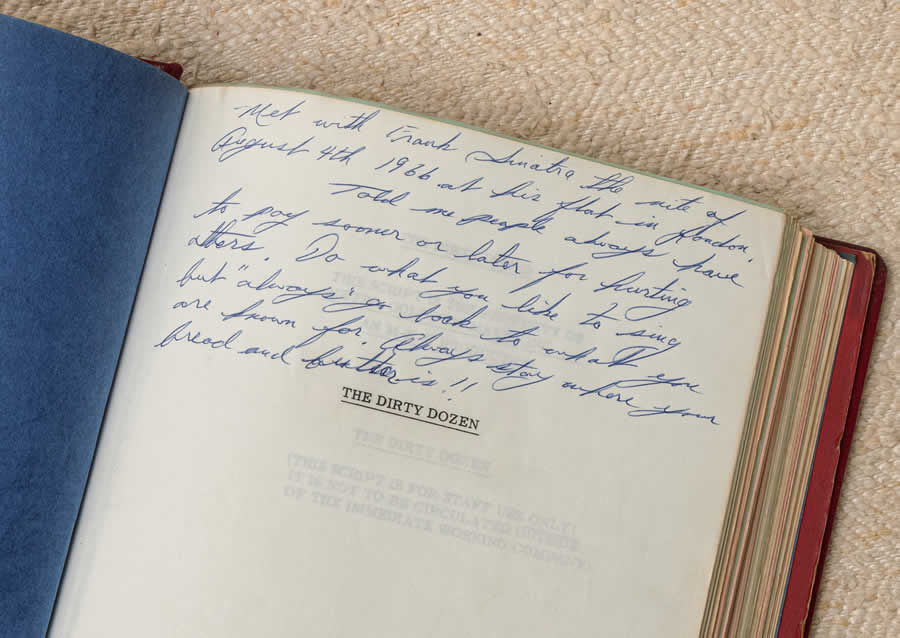

Lopez often told the story of why he exited the movie prematurely, costing him the role of hero at film’s end – because Sinatra strongly suggested it, let’s say, so his singer could return to the recording studio where he belonged. Indeed, Lopez kept in his Palm Springs home his leather-bound Dirty Dozen script, in which he wrote about going to see Sinatra at his London flat on Aug. 4, 1966.

Enlarge

Lopez wrote that Sinatra “told me people always have to pay sooner or later for hurting others,” referring to the fact the movie shoot had fallen several months behind schedule. “Do what you like … but ‘always’ go back to what you are known for,” Lopez wrote. Sinatra had advised the kid from Dallas to “always stay where your bread and butter is!!”

Enlarge

And so he did: Lopez seldom ventured back to a screen of any size, unless it was to perform for Ed Sullivan, let celebrity guests guess his identity on a quiz show, host a one-shot variety show for NBC with the Ventures as his backing band or, yes, guest-star on Adam-12. Instead, he recorded dozens of albums, stacked up numerous legislative and humanitarian honors and was even named a Goodwill Ambassador for the United States.

Soon, Lopez will be the subject of a documentary of his life that was cut short by his death; perhaps, too, his long-promised autobiography will also finally see publication. But the work, eternally youthful and ebullient and crackling, endures, far longer than mere renown ever could. In the end, it’s what separates the famous from the immortal.

“Listening to his music when I was a kid, there was an electric thing that happened with me,” says his nephew Trini Martinez. “I wanted to do that, to create that electricity. To all of us, he was like a hero. Not just because of the music or his celebrity, but because he was giving and very loving and took time out for us as a family. He would come home for the holidays, and it was awesome. We would go to the airport to pick him up, and when he walked in, people noticed. It was like, Wow.”

ROBERT WILONSKY is a staff writer at The Intelligent Collector.

ROBERT WILONSKY is a staff writer at The Intelligent Collector.

This article appears in the Spring 2021 edition of The Intelligent Collector magazine.