FRED RAY AND MORT MESKIN MIGHT NOT HAVE THE NAME RECOGNITION ENJOYED BY THEIR MORE WELL-KNOWN PEERS, BUT THESE ARTISTS’ ENDURING CONTRIBUTIONS HELPED DEFINE THE COMIC BOOK INDUSTRY

By Robert Wilonsky

Last year someone posted to Reddit this question: “What Golden Age artists are really good?” The responses were obvious and inevitable, among them such revered titans as Frank Frazetta, Lou Fine, Will Eisner, Jack Cole, Bill Everett, Alex Schomburg, Wally Wood, Graham Ingels, Matt Baker and Jack Kirby. Elsewhere, the Internet answers that query by offering figures carved into comicdom’s Mount Rushmore: Joe Shuster, Superman’s co-creator; Bob Kane, who, with Bill Finger, gave birth to the Batman; Carl Burgos, who first lit the Human Torch’s flame; and Jerry Robinson, co-creator of Robin and the Joker.

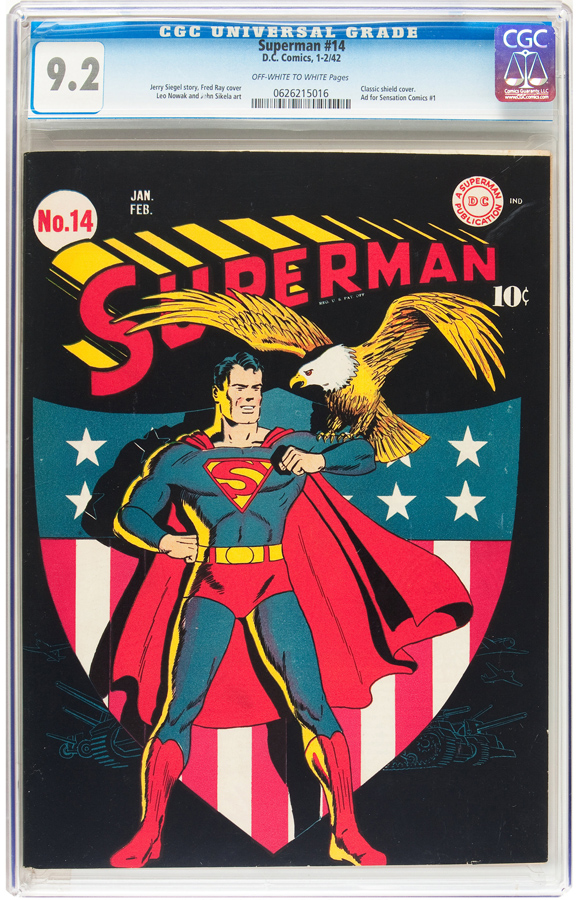

But no matter how far you fall down the Golden Age rabbit hole, no one ever mentions Mort Meskin, who made comic panels shimmer like movie screens, or Fred Ray, whose star-spangled cover for Superman No. 14 ranks among the most revered and imitated images in the medium’s history. Both men helped define the nascent medium almost as much as any better-known bold-faced legend: Meskin’s contributions fill two books (2010’s From Shadow to Light: The Life and Art of Mort Meskin and 2012’s Out of the Shadows). And, with little fanfare and even less credit, Ray rebranded Superman with the “S” across his chest that’s familiar to today’s readers.

Yet, seemingly, only the old-timers and die-hards speak of both men with the admiration of which they’re so richly deserving.

“That’s likely because their careers had ended by the time fandom started,” says Heritage Auctions Executive Vice President Todd Hignite. “Comic fans had to look back and discover them, and, sure, once you do the research and do the work and see the art, everybody is very respectful toward those guys. But they didn’t do as much work as those other guys, and they ultimately weren’t in the consciousness as much as, say, Jack Kirby.”

COMICS & COMIC ART SIGNATURE® AUCTION 7341

September 14-17, 2023

Online: HA.com/7341

INQUIRIES

Todd Hignite

214.409.1790

ToddH@HA.com

There is a good reason why both men merit mention and attention now: Two scarce works by Meskin and Ray appear at auction for the first time among the centerpiece offerings in Heritage’s September 14-17 Comics & Comic Art Signature® Auction. Each ranks among the most significant offerings in Heritage’s history.

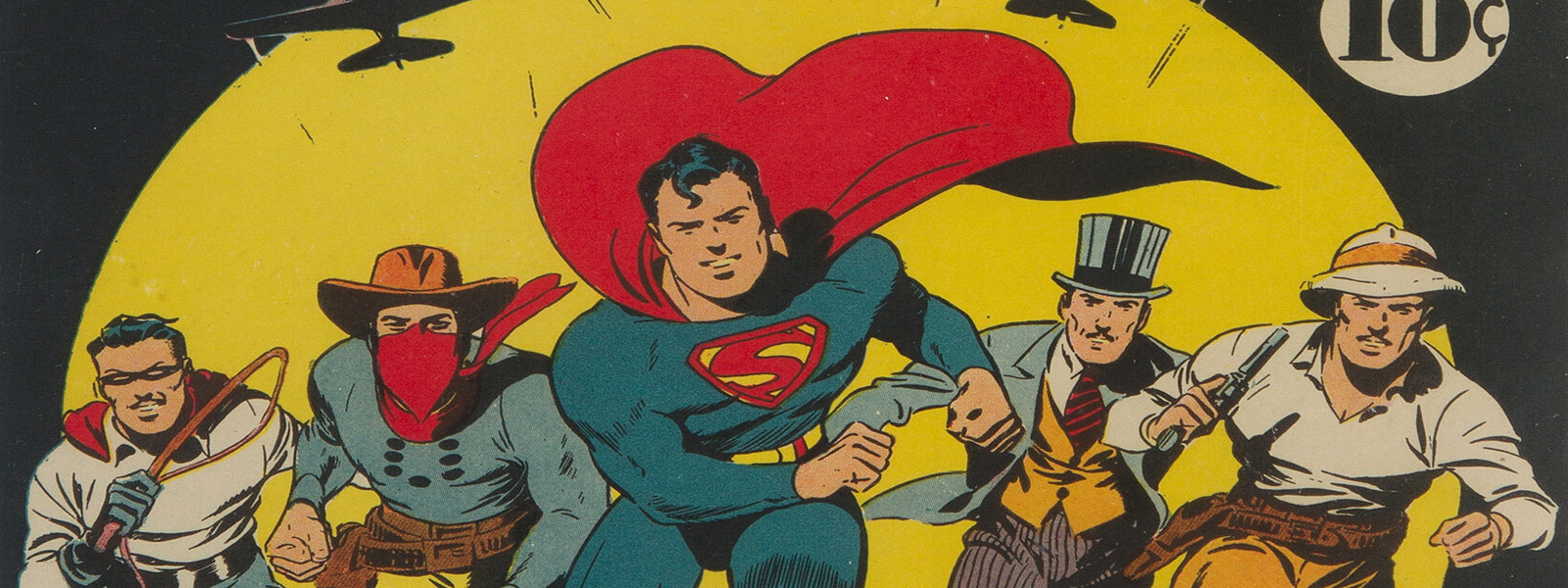

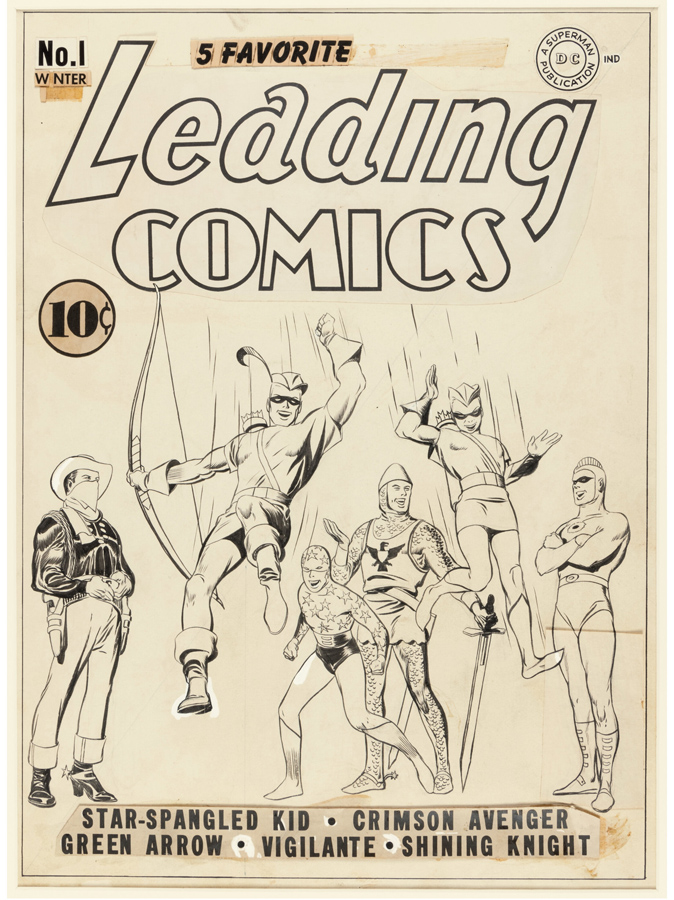

From Meskin comes this original, twice-up scale cover to DC’s Leading Comics No. 1, which, when published in December 1941, marked the debut of the Seven Soldiers of Victory, among them Green Arrow and sidekick Speedy, Vigilante, Star-Spangled Kid, Shining Knight and the Crimson Avenger. The group, otherwise known as Law’s Legionnaires, essentially comprised heroes who didn’t make it into the Justice Society of America – though by 1972, they’d all appear on the cover of Justice League of America No. 100, which began a three-issue arc about how DC’s modern-day heroes had no memories of the Seven Soldiers.

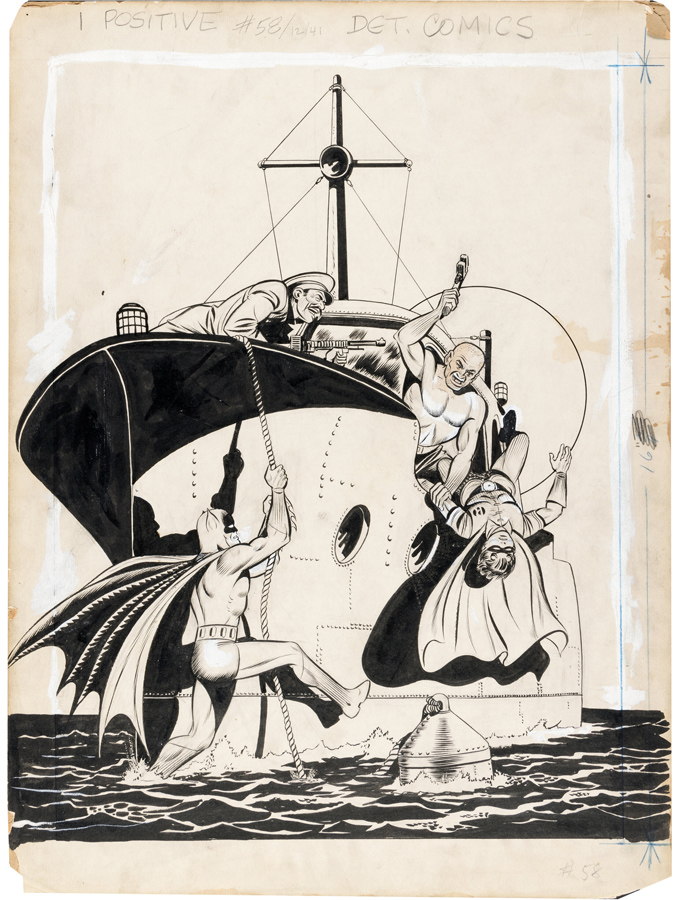

Ray is represented in this auction by no less a landmark work: the original cover of Detective Comics No. 58, also published in December 1941 and a collaboration with Jerry Robinson. Though best known for his work on Action Comics and Superman during the 1940s, Ray here, with Robinson, draws Batman and Robin in action – and in peril, Robin especially. The main story within, “One of the Most Perfect Frame-Ups,” elevates this to milestone status: Inside, readers first met “the strange, almost ludicrous figure of The Penguin.”

Enlarge

Ray, the man who put a baseball bat in Batman’s hands on the cover of World’s Finest Comics No. 3, did just three Detective covers. It’s astonishing that any of them survived, much less the cover of a book DC Comics is reissuing this month as a facsimile reproduction.

“Fred Ray was one of the inventors of superhero art,” Hignite says. “And Meskin’s influence was huge, from Joe Kubert to Alex Toth and on and on. He was a true artist’s artist.”

Fred Ray was one of the inventors of superhero art. And Mort Meskin’s influence was huge, from Joe Kubert to Alex Toth and on and on. He was a true artist’s artist.”

–Todd Hignite, Executive Vice President, Heritage Auctions

In fact, Meskin’s name appears on Page 7 of the enormous The Golden Age of DC Comics: Kubert talks about how his first job at DC was working as Meskin’s inker, while modern-day writer James Robinson notes that Meskin’s art was “a kind of fusion between the energy of Kirby and the cinematic structure of Jerry Robinson.” DC’s longtime publisher Paul Levitz adds that “there’s also a bit of Will Eisner” in Meskin’s work.

Meskin, the son of a man from Kyiv and a woman from Manhattan, was born in Brooklyn in 1916 and grew up absorbed by the pulps – The Shadow, in particular. He served as the art editor of his high school newspaper and studied at New York’s Art Students League and Brooklyn’s Pratt Institute, from which he received his degree in 1937, then went to work for Eisner and Jerry Iger, who by then had put together the anthology series Jumbo Comics for publisher Fiction House. Meskin, deemed the best and quickest in the studio stable, made his debut in 1938 illustrating Sheena, Queen of the Jungle as she swung from the British press to American shores.

In his introduction to From Shadow to Light: The Life and Art of Mort Meskin, Jerry Robinson recalls meeting Meskin two years later. Robinson wrote that the artist became his “mentor, colleague, partner, collaborator, confident and a lifelong friend.” He was especially impressed by Meskin’s academic bona fides; he was among the few comic artists at the time who’d gone to school to learn how to draw.

“Mort knew how to tell and pace a story,” Robinson wrote. “His pages flow from panel to panel and page to page.”

And when they weren’t working, the two men went to the movies, absorbing all they could from filmmakers who used moving pictures to tell their stories. As Meskin told artist and historian Jim Steranko for his invaluable two-volume History of Comics, “Citizen Kane influenced us a great deal, all of us. We were very excited about it and spent quite a bit of time discussing it, employing its elements in our work. There was a contest as to who saw it the most times.”

That influence is apparent even on the cover of Leading Comics No. 1, which sees Green Arrow and Speedy dropping in on their fellow Soldiers. Even the static couldn’t stay still. That cover was among his earliest works for DC, then known as National, where he drew, among others, Vigilante, Wildcat, Starman and Johnny Quick.

Another comics historian, sci-fi writer Ron Goulart, profiled Ray for The Comics Journal in 2013 and noted that the Philadelphia native was a history buff and a student of more “serious” illustrators, among them N.C. Wyeth and Frederic Remington. When he was 18, in 1940, Ray went to DC – then called Detective Comics, Inc. – and submitted his portfolio, which scored him a $35-a-week gig doing “spot illustrations for the two-page text stories required in comic books in those days.”

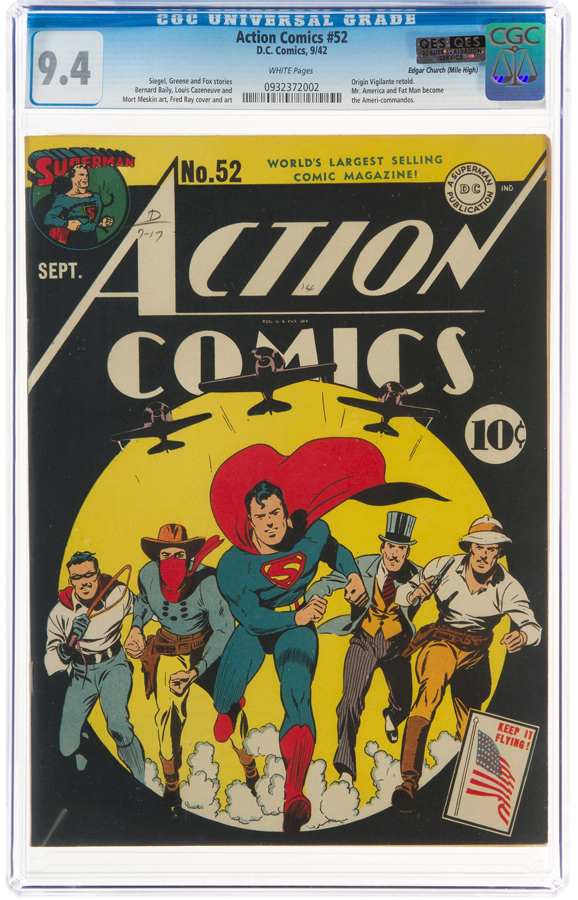

Soon after that, Ray landed the Superman job and counted among his works the cover for Action Comics No. 52, which showed “the magazine’s other major characters running side by side toward the reader,” Goulart wrote, among them Superman and Vigilante. As Goulart noted, that cover “was one of his most striking [images that] has been reprinted, and copied, in various places” since its publication in 1942.

Ray, who would also contribute the art for “Congo Bill” tales in Action, was sidelined by four years in the service and, upon his return, enrolled at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. By 1950 Ray was given his title with writer France Herron: DC’s Tomahawk, about the exploits of 18th-century frontier hero Tom Hawk.

“In Ray, Tomahawk had found his ideal illustrator,” said comics historian R.C. Harvey via Goulart. “Through careful research Ray brought absolute authenticity to his rendering of colonial America.” Ray held that job for nearly 20 years until he left comics behind. As Goulart wrote about Ray’s move to illustrating historical and military magazines in the 1970s, the artist believed his “style and subject matter were dated and no longer called for.”

As far as Ray was concerned, Goulart wrote, “comic books had been simply one phase of his long career and one that he was not particularly nostalgic over, nor much interested in reminiscing about.”

Ray, who died in 2001, might have been tickled to see one of his old covers among the new releases in comic shops this month; more likely, he wouldn’t have cared at all. But to know the real thing – that original cover to that historic Batman book – still exists is nothing less than exhilarating. After all, the man loved history. God knows he made enough of it.

ROBERT WILONSKY is a staff writer at Intelligent Collector.

ROBERT WILONSKY is a staff writer at Intelligent Collector.