STEVE SOBOROFF’S LEGENDARY ASSEMBLAGE FEATURES WRITING MACHINES FROM THE LIKES OF ERNEST HEMINGWAY, HUGH HEFNER, TRUMAN CAPOTE AND TENNESSEE WILLIAMS

By Robert Wilonsky

Like so many collections, it began with a single purchase made on a whim – in this case, the typewriter used by a Pulitzer-winning sportswriter. The man who bought the machine, Steve Soboroff, was a fan of the man who used it, revered Los Angeles Times columnist Jim Murray, whose words Soboroff devoured each morning, especially after nights when Dodgers pitcher Sandy Koufax hurled fastballs using The Left Hand of God. Soboroff wanted the 1940 Remington Model J so desperately that he outdueled two others competing for it at auction in 2005: the Los Angeles Times and the Los Angeles Dodgers. It was a hell of a score.

Enlarge

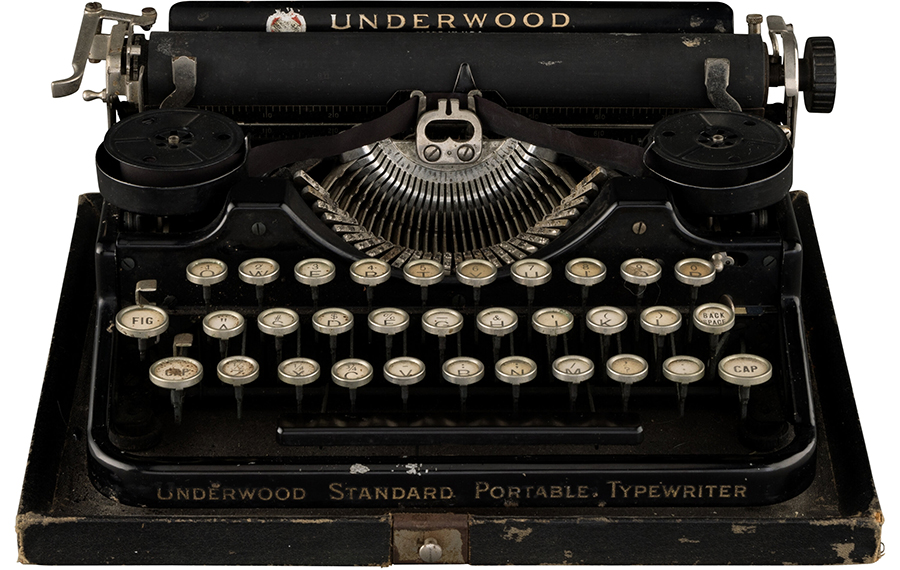

Not long after, Soboroff put another typewriter on the shelf beside Murray’s – a 1926 Underwood Standard that belonged to Ernest Hemingway and was used during the author’s legendary sojourns to Cuba. More machines followed in short order, each a typewriter that once belonged to someone who had appeared on the cover of Time. Novelists and playwrights, among them Jack London, Tennessee Williams, George Bernard Shaw, Ray Bradbury, John Updike and Philip Roth. Actors, including Greta Garbo, Shirley Temple, Mae West, Julie Andrews and a typewriter collector named Tom Hanks. Musicians, from crooner Bing Crosby to tenor Andrea Bocelli. Visionaries. Journalists. The famous. The infamous. Playboy creator Hugh Hefner. Samuel T. Cohen, inventor of the neutron bomb. And Ted Kaczynski, the man called Unabomber.

Enlarge

The result: “The World’s Greatest Typewriter Collection,” as the Huffington Post called Soboroff’s assemblage in 2015, which has been written about in outlets ranging from ESPN to The Atlantic and exhibited in myriad institutions, among them the Paley Center for Media, where a scheduled four-week stint stretched well past 14 months. The collection, assembled over two decades, was even the subject of a Jeopardy! question in December 2015. Just last year, Soboroff donated six of his treasured typewriters to the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History.

The remaining 33 from his vaunted collection will serve as the centerpieces of Heritage’s December 15 Historical Platinum Session Signature® Auction. A portion of the auction’s proceeds will go toward one of Soboroff’s favorite nonprofits: the Jim Murray Memorial Foundation, which funds scholarships for undergraduate journalism students.

HISTORICAL PLATINUM SESSION SIGNATURE® AUCTION 6280

December 15, 2023

Online: HA.com/6280

INQUIRIES

Francis Wahlgren

212.486.3738

FrancisW@HA.com

“The moment I put my hands on Murray’s typewriter, I was hooked,” Soboroff says. He wondered how many of his favorite columns spun out of that Remington. He pictured the columnist pounding away on those keys. It was a typewriter, time machine and the tool of an artist – in this case, one of Soboroff’s favorites. It brings to mind something Tom Hanks wrote in his foreword to the 2017 book Typewriters: Iconic Machines from the Golden Age of Mechanical Writing. Hanks listed 11 reasons why someone uses a typewriter, among them, they create “one-of-a-kind work,” which is to say, art.

“That’s it,” Soboroff says. “To me, these typewriters were like Picasso’s paintbrushes. A lot of these people swore these typewriters helped with their writing. Bocelli wrote to me on that typewriter in Braille and said it was a partner in creating his poetry. Harold Robbins’ wife told me you couldn’t get through to him when he was on that typewriter. He would become the character he was writing about. These typewriters were their partners.”

Enlarge

Soboroff, who in August wrapped a decade-long run as president of the Los Angeles Board of Police Commissioners, was what ESPN once called “the driving force behind the development of Staples Center and the luring of the Lakers and Kings from the Forum in Inglewood.” He also helped the Clippers build a $50 million practice facility in the Playa Vista neighborhood and, in 2011, briefly served as vice chairman of the Dodgers.

He says his run on the police commission taught him one thing about collecting: “Everything is a fake until it’s proven real. I didn’t trust anything. I had to have three sources that showed me it was real, such as a photo, a letter from the family, a typescript match, original documentation. I call it forensics.”

Enlarge

Soboroff also had just one rule as he painstakingly filled out his collection over two decades: The typewriters had to belong to people who appeared on the cover of Time. Just one of the 33 in this auction breaks that rule.

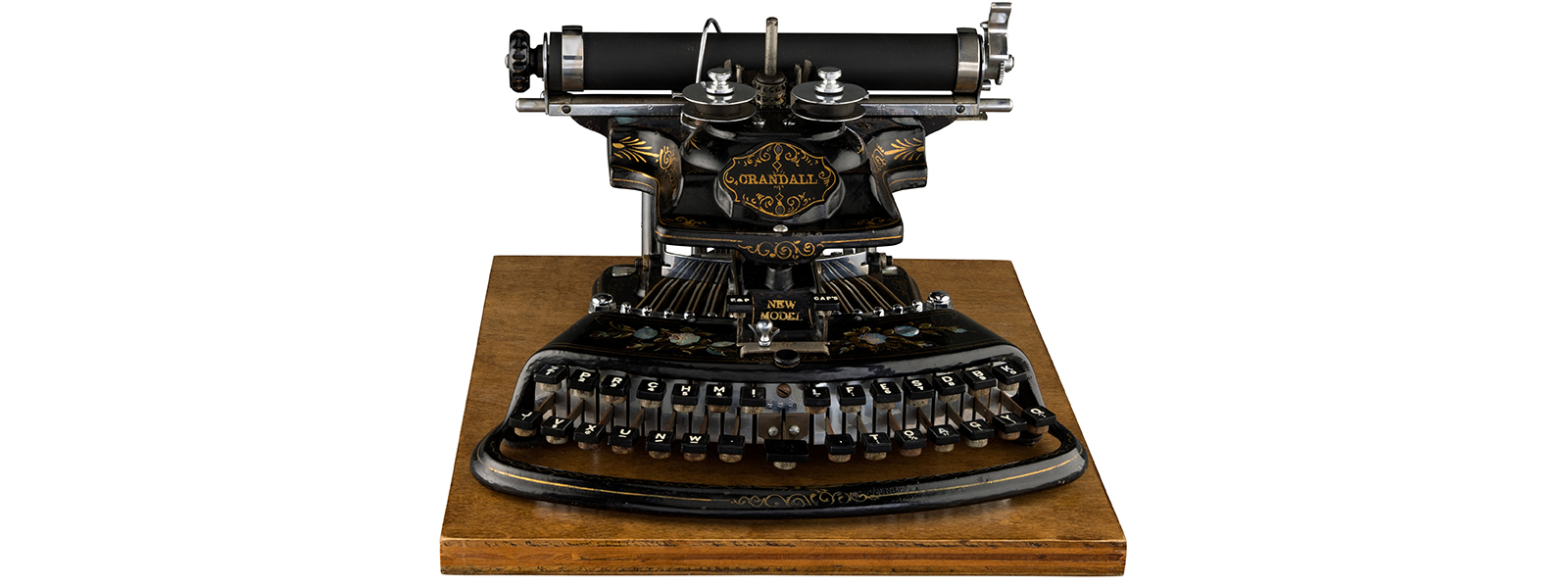

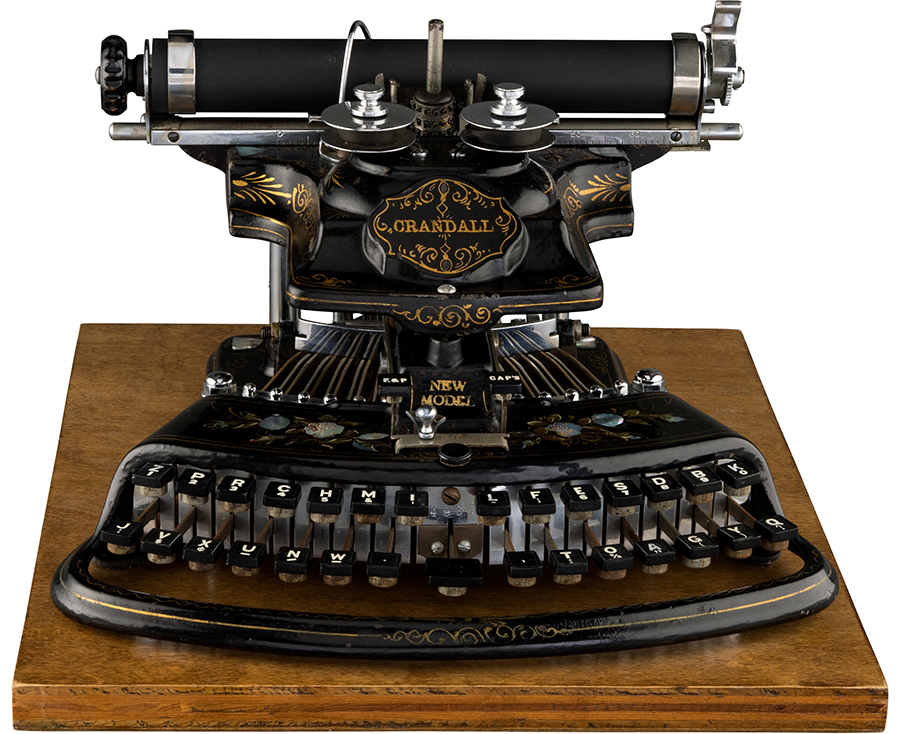

That would be the 1887 Crandall New Model, named after its inventor, Lucien S. Crandall. It’s among the most beautiful in Soboroff’s collection and was purchased because of its significance and condition.

Upon patenting the so-called type-sleeve machine in 1879 and bringing it to market shortly after, the Crandall Machine Company of Groton, New York, claimed it made a “strictly first-class two-handed Typewriter, inferior to none in utility, range of work, speed, and convenience.” It cited among the machine’s myriad benefits: The user could always see what they were typing – a first! – and its ability to type in eight styles in English. The company also boasted that it was $50 cheaper than its $100 competitors and proclaimed it “The Writing Machine of the Period.”

“Mine is in the finest condition of any Crandall in the world,” Soboroff says. “The prettiest of the pretty.”

Enlarge

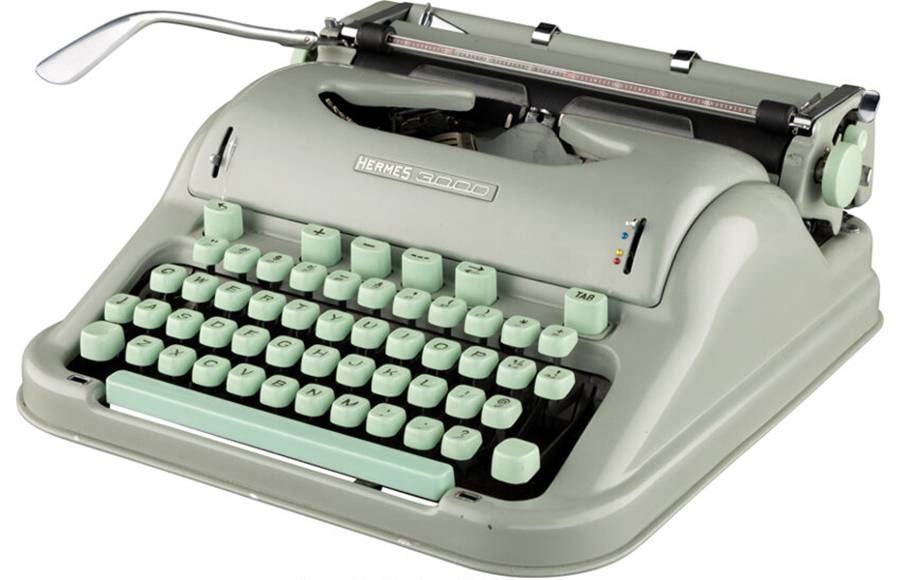

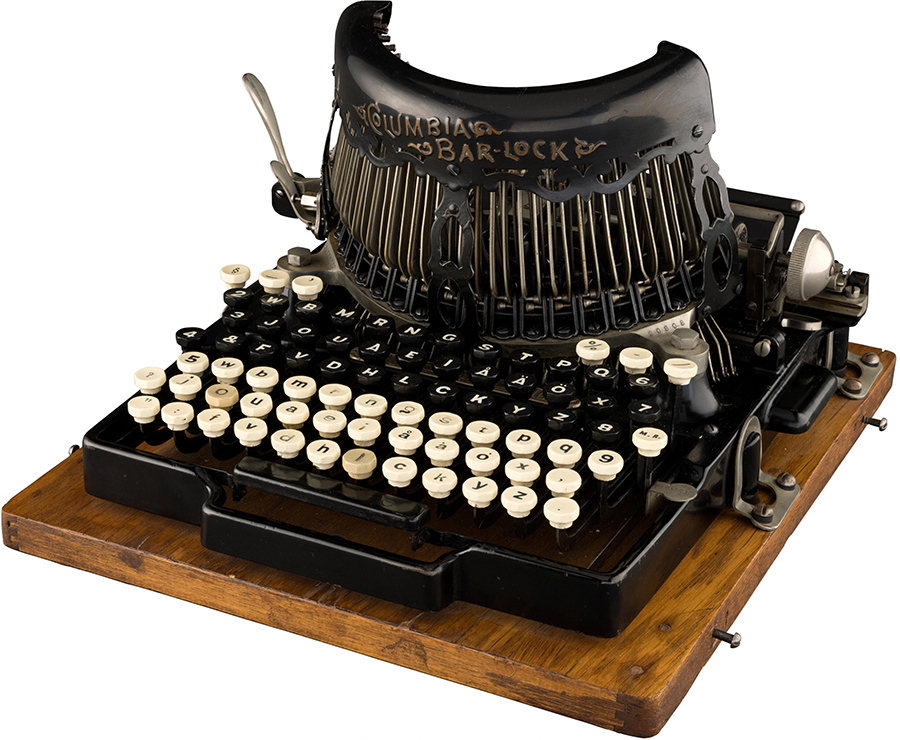

Jack London’s 1902 Bar-Lock #10, made by the Columbia Typewriter Manufacturing Company, is among the most surreal offerings in Soboroff’s collection, as it looks almost nothing like its modern-day contemporaries. As the American Writers Museum noted in 2020, when the typewriter was part of its “Tools of the Trade” exhibit, “There are separate keys for lower and upper case letters and there is also a lack of an exclamation point – London would have had to first type a period and then added a capital ‘I’ above it.” Its keyboard also boasts a wild layout: “2WBMRN” rather than the standard “QWERTY” along the top row of keys.

London, whose 1903 novel The Call of the Wild was once required reading in every elementary school English class, was famously among the most prolific authors of the 20thcentury, having banged out more than 200 books, short stories and essays during his career as literature’s premier adventurer.

Ernest Hemingway’s 1926 Underwood Standard is perhaps the most significant in Soboroff’s collection.

Hemingway used the machine to write his letters from Finca Vigía, his estate near Havana, some 2,500 of which are stored at the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum. As the Raab Collection noted earlier this year, those missives “touch upon writing, life, filming The Old Man and the Sea, fishing, travel, and, perhaps most importantly, death and the afterlife, including his near-death experience in two airplane crashes.”

As numerous media outlets have recounted, Soboroff went to great lengths to ensure the Underwood was real, taking it to the Kennedy Museum in Boston and matching it to those legendary dispatches. As the Los Angeles Times reported in 2012, “A lab found that the type matched” the typewriter. But that wasn’t the end of the story.

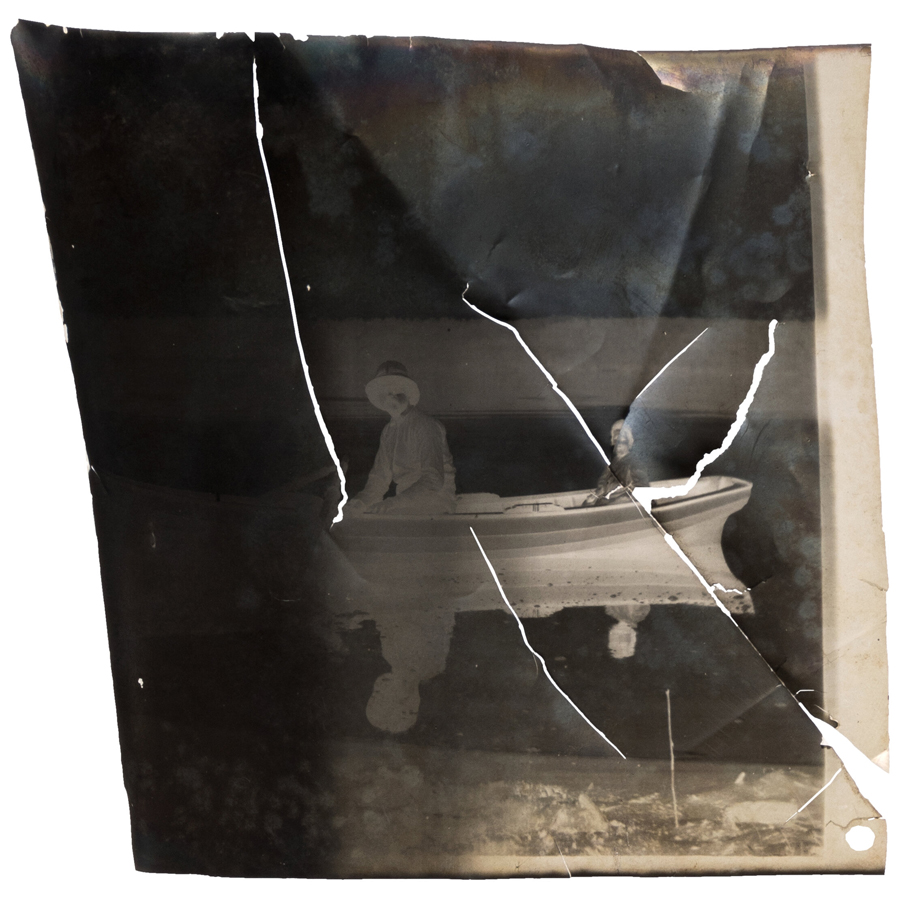

Soboroff was getting ready to display his trophy among his other prized typewriters when he realized some bits of something were beneath its body. ESPN reported in 2015 that Soboroff found what he “thought were old, burned strips of bacon.” They were, in fact, photo negatives – or, at least, what remained of them.

Esquire noted that “after having the images restored to some degree,” Soboroff sent them to Sandra Spanier, General Editor of the Hemingway Letters Project, who realized what they were: photos of Hemingway as a small child taken at the family’s cottage on Walloon Lake in Michigan. Esquire, which counted Hemingway among its most notable contributors, published some of the photos a decade ago.

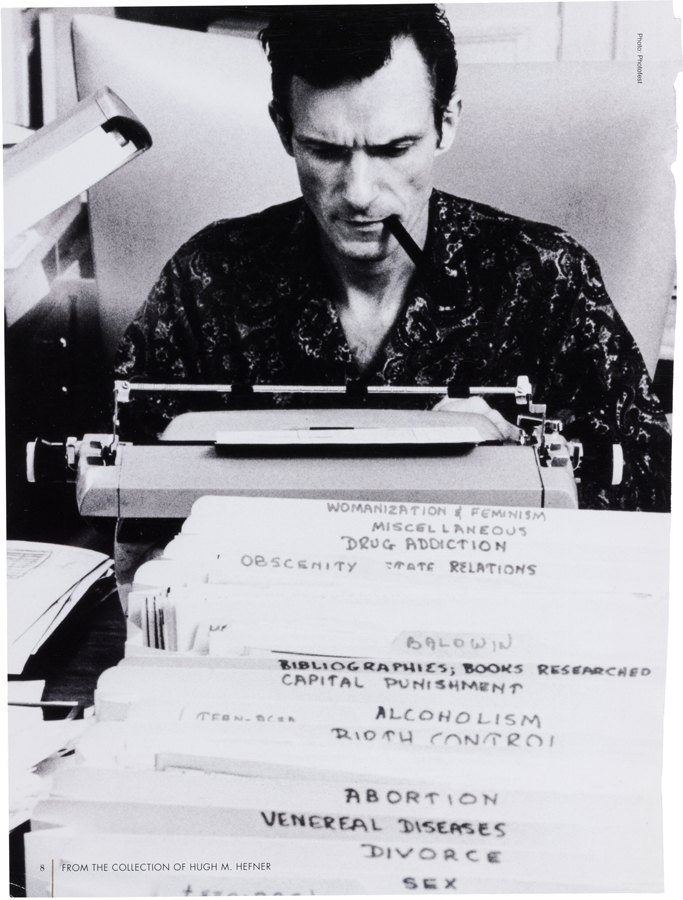

Some typewriters can be linked to critical moments in their owners’ lives, such as Hugh Hefner’s 1962 Royal Empress, which the Playboy publisher uses in a photo where he’s clad in his pajamas while smoking his ever-present pipe. In front of Hef sits a rack of folders, each marked with the topics that filled his magazine, among them, “Divorce,” “Birth Control,” “Abortion” and “Capital Punishment.” And as the American Writers Museum noted of Tennessee Williams’ 1936 Corona Junior, purchased while he was attending Washington University in St. Louis, “it is likely that his first play, Battle of Angels, which was first performed in 1940, was written on this very typewriter.”

But Soboroff didn’t necessarily care if an author had written something beloved or bestselling on a machine; to him, it was significant only if they owned it – and, of course, if he could prove its provenance.

“I am a populist,” he says. “I was a B and C student. If it doesn’t click with me, I don’t think it clicks with the public.”

Take E.M. Forster’s Oliver Standard Visible Writer No. 3, which Soboroff bought at auction in 2014. It’s unlikely Forster, the author of A Room with a View, Howards End and A Passage to India, wrote any of his significant works on the machine. As was mentioned when the typewriter first sold in 2014, Forster had a well-known dislike toward machines of any kind – as well documented in his prescient 1909 story The Machine Stops, which reads like a first draft of The Matrix or a time traveler’s warning about the damage wrought by reliance on ChatGPT.

Yet Soboroff had to have the machine, produced in 1896 and hyped as the first typewriter sold to the everyday user. It was also passed down to a friend and later exhibited at The University of Warwick Library. Soboroff was so excited he’d acquired the typewriter he told a Southern California public radio station in 2014, “I didn’t let this one get away! Been working on it for months :)”

Once Soboroff got hooked, he was all in, and in short order, his collection became so well known that celebrities famously inquired about buying pieces of it, though Soboroff rejected such requests. Some L.A. media outlets documented almost every one of his purchases, which often came from relatives of their previous owners, such as Miranda Margaret Updike, who told Soboroff myriad tales about her father, John, before selling him the Rabbit, Run author’s 1967 Olympia 65C.

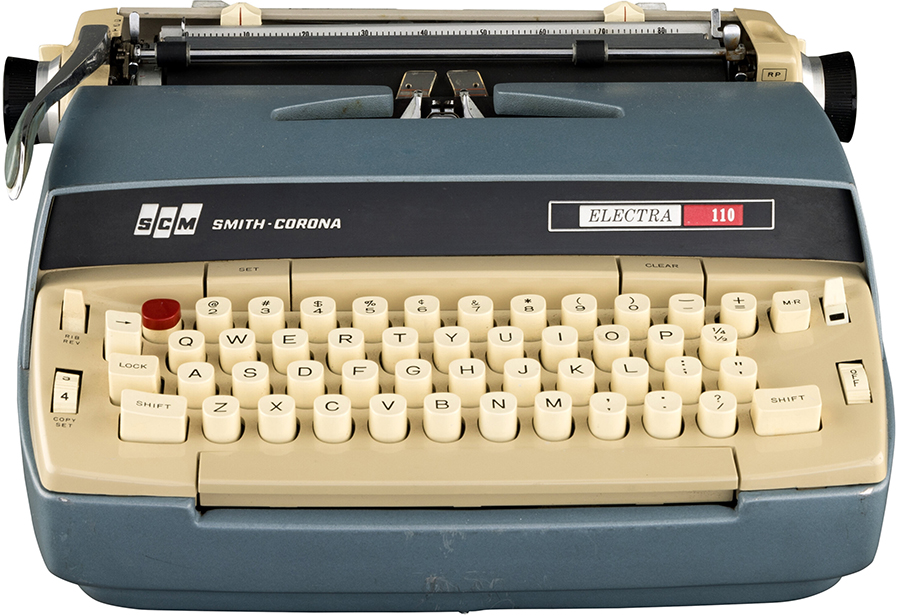

Tales grew legion about Soboroff’s efforts to acquire typewriters on which he’d set his sights. He says he spent five years trying to buy Truman Capote’s 1961 Smith-Corona Electra 110 from Joanne Carson, the second wife of Johnny Carson and Capote’s confidante. Joanne kept a writing room for Capote at her Bel Air residence, which he used whenever he visited Los Angeles. When Soboroff found out, he called Joanne to see if he could buy Capote’s Smith-Corona. She refused to talk to him for five years – until her house was burglarized, or so she thought, and she noticed the man trying to buy Capote’s typewriter was also president of the Los Angeles Police Commission. She called Soboroff and asked him to come over, which led to the beginning of a friendship.

“I didn’t think I’d ever get the typewriter,” he says. “One day, she called and said, ‘Come over.’ When I did, she had the typewriter with a ribbon on it. I said, ‘I can’t take it. I have to buy it.’ She said, ‘You remind me of Truman, and I want you to have it.’” Soboroff says he did indeed pay her for the typewriter – “a lot,” he adds.

The breadth of the collection is unparalleled: For now, at least, only Soboroff can say he owns both the 1939 Corona Standard Barbra Streisand’s character gifts to Robert Redford’s writer in The Way We Were and one of the Unabomber’s 1968 Montgomery Ward Signature Portables, the latter of which he bought at an FBI auction. They’re bookends of a collection that has traveled the country and captivated crowds and proved true the old axiom that stories live in typewriters, and you might get a different story if you try a different typewriter.

“They’ve become part of my identity, something no one else in the world did, and I was lucky enough to be recognized for it,” Soboroff says of his decision to auction this estimable assemblage of writing machines. “But every time I saw them in my study, I said, ‘This is not right.’ That led me to this point, and I hope the people lucky enough to get them will celebrate them more than I can. I believe these typewriters belong to the world.”

ROBERT WILONSKY is a staff writer at Intelligent Collector.

ROBERT WILONSKY is a staff writer at Intelligent Collector.