FIFTY-SEVEN YEARS AFTER JOHN CARLOS’ LEGENDARY BLACK POWER SALUTE, HIS JACKET FROM THE MEXICO CITY GAMES HAS FINALLY MADE ITS WAY HOME (AND TO AUCTION)

By Robert Wilonsky

A plain cardboard box from Senegal arrived at an Atlanta address not long ago. Inside was a blue tracksuit jacket. Nothing fancy, a standard-issue Wilson navy-blue zip-up. A red-and-white “USA” was sewn diagonally onto the left chest. Below it were two white pieces of fabric affixed to the jacket, upon which were printed the numbers “25” and “9” and, below them, the words “JUEGOS DE LA XIX OLIMPIADA MEXICO 68,” accompanied by the Olympic logo.

For 79-year-old John Carlos, that cardboard box might as well have been a time machine. As he reached inside, his eyes began to fill with tears. In an instant, he says now, “I felt younger, as if that was yesterday.”

More than 20,000 yesterdays ago – on October 16, 1968, to be precise – Carlos took third in the 200 meters at the Olympic games in Mexico City. His USA teammate Tommie Smith came in first. They stood on the podium, received their medals and then raised a fist toward the Mexico City sky in protest, resulting in a ticket home the next morning and immortality forever after.

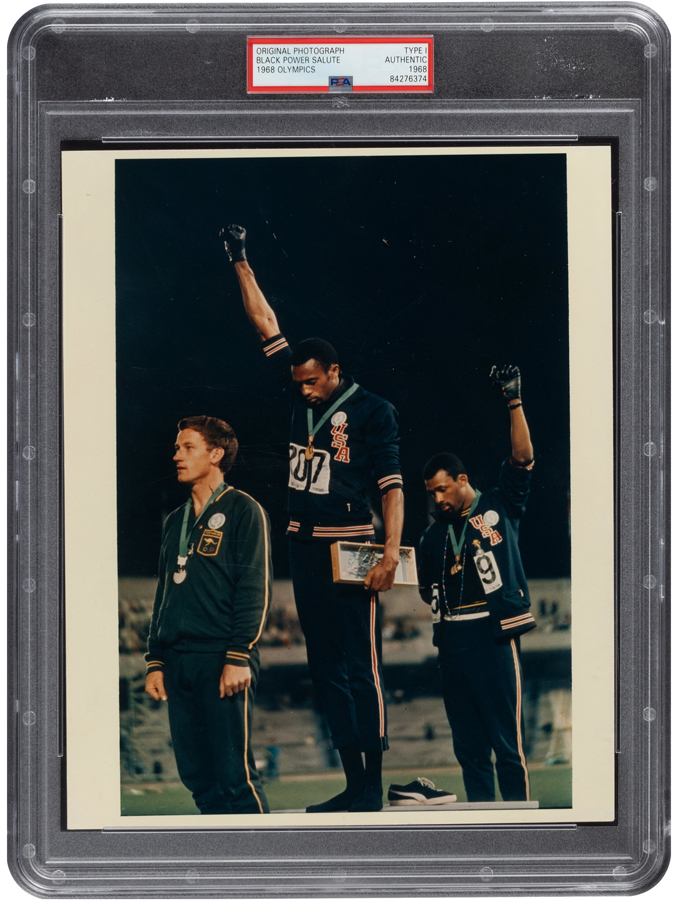

John Carlos (far right) raises a black-gloved fist in protest of racial inequality alongside teammate Tommie Smith at the 1968 Summer Olympics.

Before he left Mexico, Carlos says now, he saw a long-distance runner from Senegal wearing “a beautiful outfit.” Carlos offered to trade him his jacket, which the man accepted. “Didn’t have no more thought about it,” he says, until a couple of years ago, when that Senegalese runner died and his nephew reached out to tell Carlos he had something of his he’d like to return: the jacket, preserved as though it had once belonged to “a king.”

“When I opened the box and just touched it, man, I was blown away,” Carlos says. “My wife looked at me and said, ‘You all teared up.’ I said, ‘Baby, you just don’t realize what I’m going through right now,’ in terms of what was flowing through my mind, flowing through my body, the energy that I had.”

Smith’s tracksuit is in the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History & Culture. Carlos is going to sell his during Heritage’s February 22-23 Winter Platinum Night Sports Auction, with most of the auction’s proceeds going back to the family who kept such good care of the jacket since October 1968.

Most people know Carlos and Smith only as two-dimensional icons, striking young men captured on a podium, the names attached to the clenched fists in John Dominis’ photograph taken for Life or the video transmitted to homes during dinnertime on a Wednesday evening in 1968. The International Center of Photography calls Dominis’ photo of Carlos and Smith “one of the most iconic photographs capturing the struggles of the civil rights movement.” Sports Illustrated’s Tim Layden in 2018 labeled it “a still life of protest.”

You know the picture, whether you’ve seen it once or a thousand times: two Black American Olympians wearing Olympic medals and black gloves. As “The Star-Spangled Banner” began to play, Smith raised his right arm straight as if to punch a hole in the sky; Carlos, his left, slightly curved. Their heads are bowed in the photograph; their eyes are closed, and their feet are bare, save for black socks meant to represent the impoverished.

To represent those lynched, Smith wore a scarf; Carlos, a long beaded necklace. Carlos also wore one of his father’s military medals on his jacket, which he kept unzipped – a violation of United States Olympic Committee protocol – to reveal a black sweater covering his USA jersey. When reporters asked him why, Carlos says now, he would explain that he was “really ashamed of America because I thought America could have done so much better.” Then, now, tomorrow. “They never even printed or talked about it.”

In front of them stands a white man, silver medalist Peter Norman of Australia, who stares straight ahead, expressionless. All three men wear a white button pinned to their tracksuits.

The badge reads, “Olympic Project for Human Rights,” an initiative founded in the fall of 1967 on the San Jose State College campus by Harry Edwards, a track and basketball star turned instructor and revolutionary. Inspired by Malcolm X and supported by activists H. Rap Brown and Stokely Carmichael, Edwards offered a platform with numerous goals, chief among them staging “an international protest of the persistent and systematic violation of black people’s human rights in the United States.” Edwards believed Black athletes were being used as “political propaganda tools” and called for them to boycott the 1968 Olympics.

Smith and Carlos, two very different men from very different parts of the country, were among Edwards’ friends and acolytes. Smith was born in Texas and raised in California, the son of a sharecropper; when he wasn’t in class, he was in the fields picking cotton and grapes. Carlos was born in 1945 to a Cuba-born mother and a World War I-fighting, shoemaking father in Harlem amidst its Renaissance, not far from the Cotton Club and Savoy Ballroom.

Carlos recalls hearing Malcolm X speak when he was just 14. Only a few years later, he was running track at East Texas State, “where I see a sign that says, ‘Water Fountain Whites Only.’ No ‘Colored Water Fountain.’ Just the white water fountain. Then I saw the restroom: ‘Whites Only.’ The white restroom was pristine. The colored restroom had gnats flying and water running, no toilet paper. Before I landed, the coach had been calling me ‘John Carlos’ or ‘young man.’ When I landed and he came out, my name went from John Carlos to ‘boy.’”

And worse. Much worse.

Carlos’ USA track jacket from the 1968 Mexico City Olympics is available in Heritage Auctions’ February 22-23 Winter Platinum Night Sports Auction.

Carlos endured 18 months in East Texas until he returned to New York and then San Jose State College, where he found Edwards, Smith and the Black athletes who would spark a revolution that ignited on the podium in Mexico City in 1968. But the world was already ablaze by then. The National Archives calls 1968 “A Year of Turmoil and Change,” pointing toward race riots in Detroit and Newark and D.C., the Tet Offensive in Vietnam and the killings of “two proponents of peace,” Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in Memphis that April and presidential candidate Robert F. Kennedy in Los Angeles two months later.

The Olympic Project for Human Rights demanded numerous changes, including removing International Olympic Committee President Avery Brundage, who ensured the U.S. participated in Hitler’s Olympics in 1936, and restoring Muhammad Ali’s heavyweight championship title. The OPHR also wanted to boycott the ’68 Olympics, but it wasn’t that easy: Black athletes had sacrificed too much to reach Mexico City only to be left at home.

The way Carlos tells it, before the 200-meter finals, he told Smith he was “disenchanted about the fact the boycott was called off.” Carlos said he wanted to “make a statement” and asked Smith if he was in.

“He said, ‘I’m with you,’” Carlos recalls. “Now, when he said that, already in my mind – in my soul – I’m saying, ‘He can have the medal.’ If he’s going to stand with me in this statement that we’re going to make, he can have the medal. Medals didn’t mean nothing to me, but just based on [Smith’s] demeanor about track and field, he idolized medals and trophies and that kind of thing.”

Carlos likes to break down the race film and point out that while Smith was sprinting, he was “striding down the track,” all but ceding gold to his teammate. You can certainly see it in the video, the way Carlos turns to his left to watch Smith break toward the finish line – and the surprise on Carlos’ face when Peter Norman sprints past him for silver.

“Oh, shit, Peter Norman,” Carlos says as he revisits the race. “I forgot about Peter Norman.”

More than 50 years on, countless documentaries, essays, articles and books have dedicated ample space to “The Black Power Salute That Rocked the 1968 Olympics” (Time), the Fists of Freedom (HBO), Race, Culture, and the Revolt of the Black Athlete: The 1968 Olympic Protests and Their Aftermath (University of Chicago Press), the Black Power Salute (BBC), “The Black Athlete, Black Power and the 1968 Olympic Project for Human Rights” (a 2009 dissertation by Dexter L. Blackman of Georgia State University). Smith and Carlos have written their own books, each an equally potent retelling of the moment so memorable and often misunderstood.

On the very first page of his autobiography Silent Gesture, Smith wrote that while he stood on the podium with fist raised and head bowed, he prayed – “prayed that the next sound I would hear, in the middle of the Star Spangled Banner, would not be a gunshot.”

Carlos says now that he “never had no fear about it. Lemme tell you something. My attitude is this: You could die now, or you could die later. But bottom line … it’s about what you did between those two points.”

There are two statues of the men, too – one on the San Jose State campus called Victory Salute (Olympic Black Power) and another at the Smithsonian. In each, Carlos wears the jacket he gave away in October 1968 that made its way home long enough to reach the auction block.

“I was elated to see it, but it was hard for me to miss it because I see myself in the picture every day,” Carlos says. “But it all brought everything back: that day, that time, the festive activity we had during those Games in terms of all the different cultures, the dress, the foods. It all just flashed back. It was almost like it was a blessing from God after all these years, after all my trials and tribulations as a result of my activities in Mexico, to bring this back to me and bring it back to me fresh. It is almost like a rebirth. It was like energy.

“I felt that the stadium that we ran in Mexico City was a living organism. It wasn’t just concrete and stone. It was a vibrating and breathing entity. And that’s the exact same thing that I felt when I received the jacket in the mail.”

ROBERT WILONSKY is a staff writer at Intelligent Collector.

ROBERT WILONSKY is a staff writer at Intelligent Collector.