‘X-MEN’ WRITER EXPLAINS HOW CREATIVE TEAM PRODUCED SOME OF THE HOBBY’S MOST COVETED PAGES

Interview by Barry Sandoval

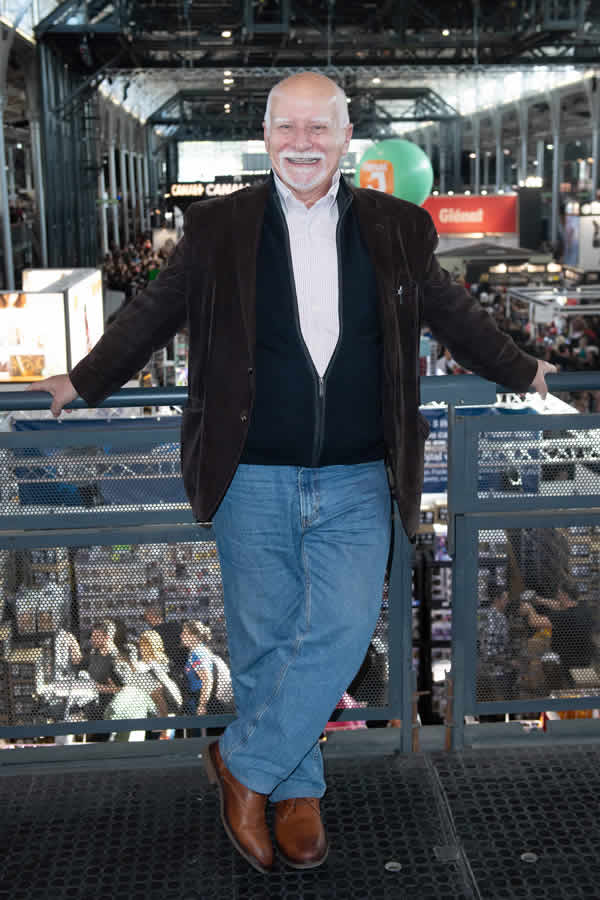

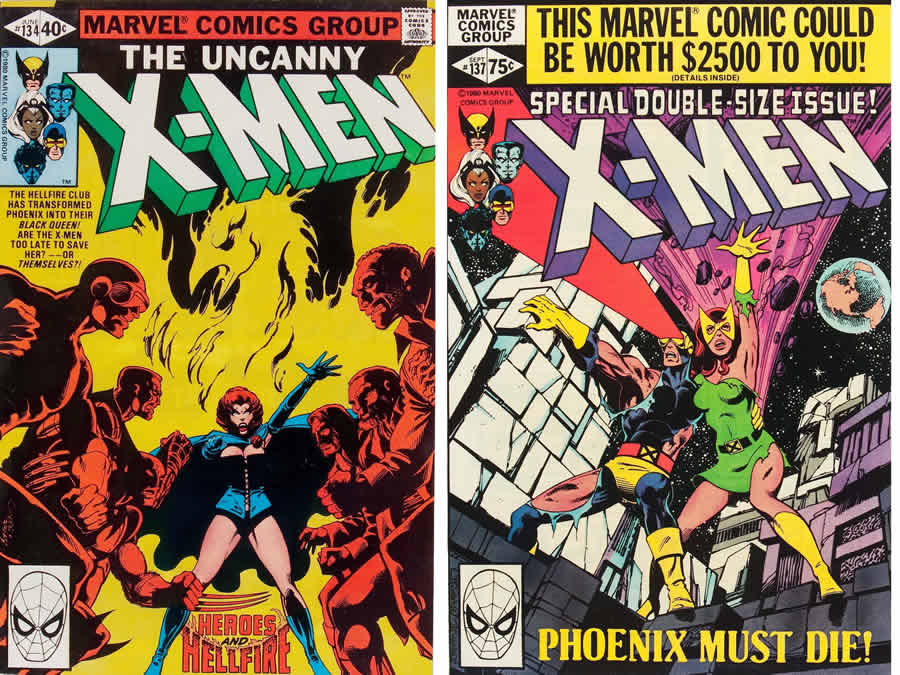

Chris Claremont likes dealing with big stuff, big metaphors, big moments, big challenges. This should come as no surprise to anyone who has read the work of the comic book writer and novelist, best known for his 1975–1991 stint on Uncanny X-Men. Claremont took time to talk about the creative process behind those legendary tales and two pages of original art from X-Men #134 and #137 he consigned to a March 2020 auction at Heritage.

SPECIAL REPORT

- MAIN STORY

- CHRIS CLAREMONT

- FRANK FRAZETTA

- VIDEO GAMES

- PULPS

Can you explain how Marvel’s policy worked with regard to writers receiving some of the original art?

The structure evolved back in the very early ’70s – the 17 story pages were split up, with a proportion to the penciler and a proportion to the inker. Over a period of time, the policy was changed further so the pages weren’t strictly to the penciler and the inker [i.e. the writer was included] and that’s how it’s been from that point on.

Enlarge

To be honest, back then there was never really a sense that there would be a significant resale market. It was just a courtesy. Most of the time, it was a random selection. In this case, considering the issues involved, I got a fairly nice couple of pages and I’ve had them for 40 years, and the time has come to move on.

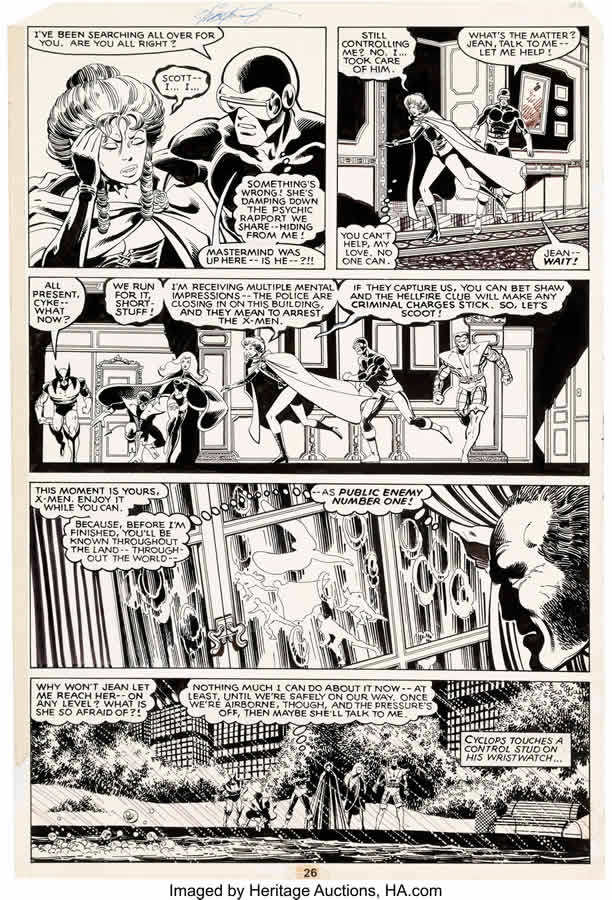

Looking at issue #134 page 26, I’m reminded how, more so than any other writer, you always presented an immediate threat to your characters and also showed the readers that even more threats were imminent.

The fun for a creator is somewhat perverse. You keep putting the characters through torture. On the page you’re referring to, you think it’s almost the calm before the storm. “We’re making our happy escape, we’ll go back to the mansion and have a drink … Oops.”

We’re trying to entice you not to use the end of a story arc as a jumping-off place. This is a serial storytelling form. I never think of the end of a story arc as an end. It’s a transition to the next arc. When we’re at a convention, someone invariably asks me “What is your favorite story” and my answer has always been “#94 through #279, page 11.” Because to me, it is like life – it has high points along the way but it is always one ongoing story. So for me, the end came when I left the book, and that’s it.

What we had fun doing is telling a multilevel story. You can read it as a simple adventure, you can read it as a complex character story, everything. And the art at its best tended to embody that.

Enlarge

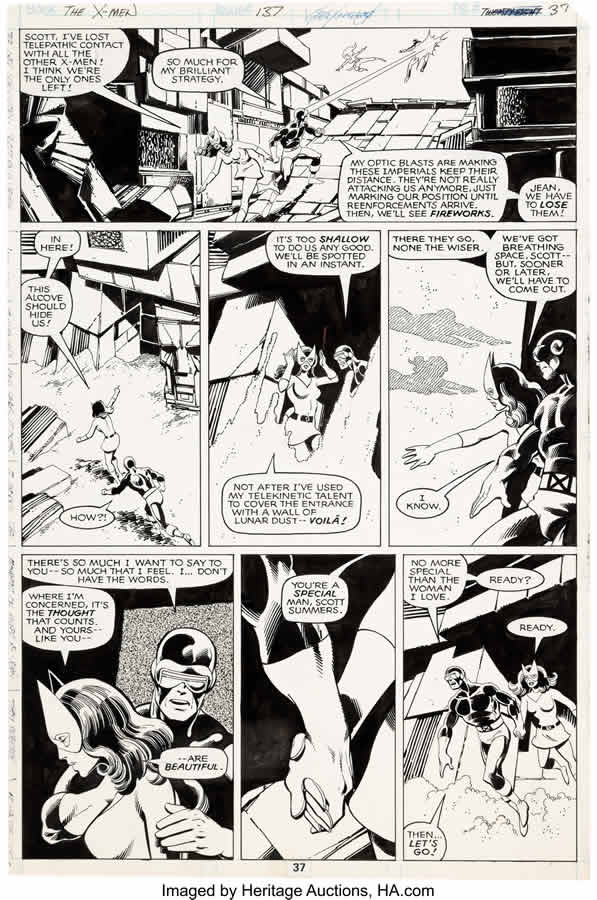

On that page from #134, Dark Phoenix is about to make her first appearance, and in issue #137, page 37, we’ve almost reached the culmination of the Phoenix saga.

The second page is a complement to the first. “We’re fighting as hard as we can, we’re on the moon, it is our last stand, there’s no way we can survive.” If we’re thinking in terms of an untold story: We have no idea how long [Scott Summers and Jean Grey] were behind that wall of moondust. Jean is a telepath [and can delve into Scott’s feelings that way] – in the space between the two panels they could have lived happily ever after. It’s like Leo DiCaprio and Kate Winslet in Titanic, except Jean Grey is the one in the water.

In this moment, they believe they’re both dead but they will face it together. Think about it: “We’re 20, we’re on the moon, why are we fighting to our deaths?” That’s the feeling I got when I first read Stan and Jack’s [Lee and Kirby’s] work eight years earlier, and that’s the feeling that I wanted to bring to readers of my work. It isn’t just “Hero fights villain, move on to the next fight.”

I always thought it was a wonderful touch that Jean puts on her old Marvel Girl costume for this last stand.

This is Jean reaching back to a more innocent, more heroic age. The problem with the Phoenix outfit is that it binds her to what Dark Phoenix did, so here is something more innocent. [But actually, the origin of the idea was that] John [Byrne] wanted to do an issue with the old costume.

In the context of this moment it works. It’s her drawing a line between Marvel Girl and Phoenix even though at that point, I think there was no line. Though John would disagree with that last statement.

Everyone remembers the ending of #137, though I think most fans know that was not the original ending that you wrote [readers can see 1984’s Phoenix: The Untold Story for the full story behind that].

[The page being auctioned by Heritage is] one of my favorite pages. That page is the essence of the decision I had to make, which is what to do with Jean. That is where it started.

Enlarge

How much time did you have to make the changes to the last few pages of the story, and what was that experience like?

John started drawing Monday. We sent the book out [to the printer] Thursday.

Even we, the creators, ended up sitting on the edge of our seat as much as the readers did! As far as I’m concerned, the new ending had a lasting effect, which is totally cool. The reader thinks it’s going to end one way and you make a sharp left turn.

Today it’s impossible to keep a secret. What was different back then is there was no news source [to leak breaking news, as happens online or on social media today], plus no one saw this coming because we changed the ending at the last minute.

It had an incredible impact but unlike some other comic book deaths I could name, there was nothing “cheap” about the death of the character.

It’s trying as much as possible to present the characters as real beings so an audience can respond to them in the same terms. You’re not casual in your relationship with the characters. With Superman, you can take it or leave it because nothing ever changes. I wanted things to change. I wanted the readers to understand that there’s a reality for these characters that is as real and valid as it is for us in life. Nobody gets out unharmed or unaffected. It all starts with caring about Jean. She and Scott are the second-longest romantic relationship at Marvel.

True, but it wasn’t a very interesting relationship until you started writing it.

The cheap answer is, I guess writers do make a difference. You don’t treat them like characters. You treat them like people. For instance, Scott’s inherent baseline is to be an a**hole whether everyone likes it or not.

Enlarge

Many of the best comic runs of the 1980s were by one person who served as both the writer and the artist, but on the X-Men, the whole creative team stood out.

You look at Frank Miller’s work, you look at Walt Simonson’s work, such energy, such passion. I find it cool. But what I loved was an opportunity to work with artists of exceptional talent and create a story. John’s and my synergy was breathtaking. It’s up to me to craft my dialog in a way that complements the art. Throwing a concept at Dave Cockrum or John Byrne and watching how they bring it to life, that inspires me in return. This is where a key difference is with the writer and the artist being separate people. Sometimes the artist’s response is out of left field, but it also can be useful, and often it’s a lot more fun than what you originally had in mind.

John is an extraordinary artist. The scenes he creates have texture and detail – and the wonder of Terry Austin as an inker is that he catches it all. Even given John’s incredibly distinctive and consistent presence as a penciler, Terry gave the art even more in terms of defining the characters.

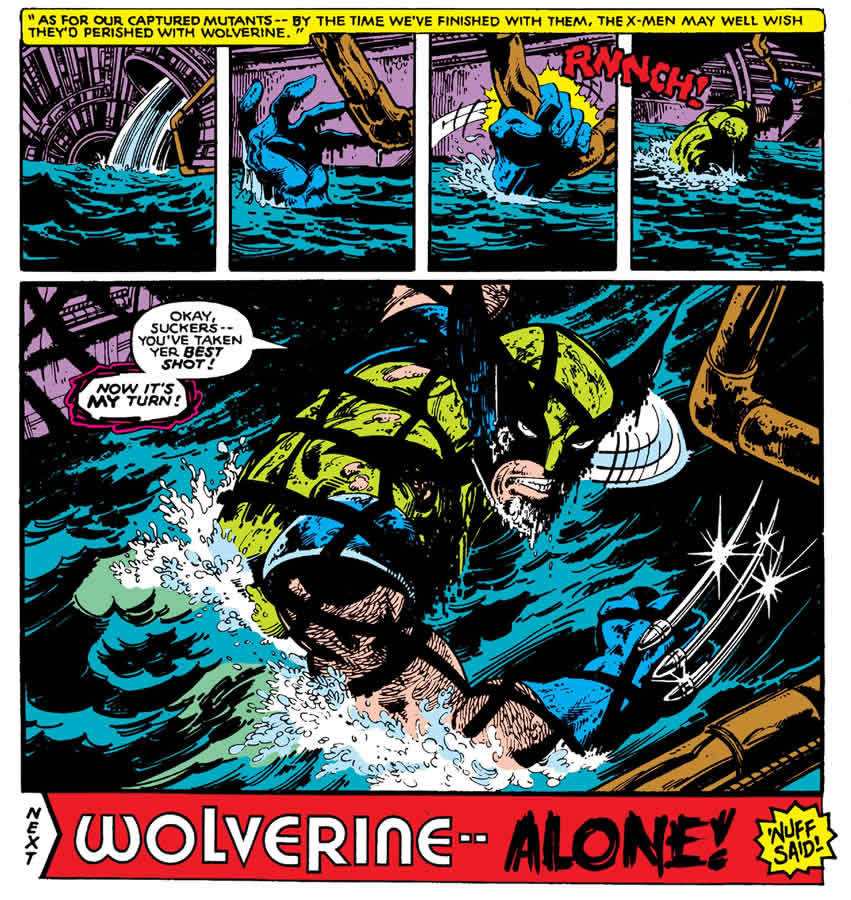

We also had what’s very rare in comics: a consistent ongoing creative team. The classic is the last page where you end up with Wolverine.

I think any X-Men fan will know what you’re referring to: the last page of #132, a five-panel sequence with minimal text, where Wolverine, who we thought was out of action, surfaces in a raging underground sewer, seething and ready to strike back.

There are times when I know when to shut up as a writer. Between John’s pencils, Glynis’ color, Terry’s inking and Tom’s lettering – the reader sees it and thinks, “The bad guys are in such trouble now.”

Enlarge

How did issue #137 do, in terms of sales and readers’ immediate reaction?

Double-size issues usually sell less than the surrounding books [owing to the higher cover price], but we didn’t lose any sales at all. It sold remarkably well for a double size issue. It sold really well for an X-Men issue.

We got 100, 150 letters. People were heartbroken. Some were really pissed. I got death threats for real that we reported to the NYPD.

We then have a pause-for-breath issue [Jean’s funeral, #138] just to remind everyone we weren’t kidding. Two issues later, John and I did “Days of Future Past,” which threw the whole thing into a kerfuffle. “You thought the last thing was something to worry about? Hello!” And we did it in two issues. You say your piece, you get off and move on to the next. “Days of Future Past,” if done in current comics, would be a 20-issue crossover.

Stan Lee’s rule was every story is one issue. You can go to two if you really have to – if you have a Galactus story you can do three, but even then, the end was Johnny Storm going off to college. You get on, you say your piece, you get off. If it’s a disaster, to quote Archie Goodwin, “You’ve got 30 days to fix it” [by coming up with a better story the following month]. Today’s continuity is so integrated across multiple arcs, if you make a misstep today, you have a problem. Of course, the way Stan did it was defined by different parameters than the current marketplace.

How were the sales of the X-Men compared to other Marvel titles at the time?

The sales were just remarkable. It was only five years since the book had been rebooted. We just kept on building and building. We were always duking it out with Frank [Miller’s Daredevil] at the top of the heap. Once Paul Smith came in [as X-Men penciller], we were alone at the top.

I’d compare it to the day [the original] Star Wars opened. I went to the Loews Theater in New York. I was there one and a half hours before they opened. I was the twelfth person there. The theater had only sorta kinda filled up by the time the movie started. But when I walked out, the line was three times around the block and it didn’t go away for three or four months. Something like that happened with the X-Men.

The point from our perspective was just to do the best story possible and let the sales take care of themselves.

Today, the neat thing is going to conventions and discovering that readers are in love with the work. To me, the thing I find extraordinary is after 40 years, I go to a convention and I’m talking to fans and signing books nonstop for two, three, four, or at the Lucca [Comics & Games show in Italy] it’s even five days! Because I’ve got people coming up and buying copies for their grandparents who read the book when they were younger and buying copies to give to their kids. I’m working on my third generation, or possibly my fourth of readers, which to a writer is like, “Holy cow!”

BARRY SANDOVAL is vice president at Heritage Auctions.

BARRY SANDOVAL is vice president at Heritage Auctions.

This article appears in the Spring/Summer 2020 edition of The Intelligent Collector magazine. Click here to subscribe to the print edition.