THE COMISAR COLLECTION TEEMS WITH RELICS FROM SOME OF TELEVISION’S MOST TRANSFORMATIVE MOMENTS. HERE, IN A SIX-DECADE TIMELINE, WE PRESENT SOME OF THE BIGGEST STARS FROM THE COLLECTOR’S SMALL-SCREEN COMPILATION.

By the Intelligent Collector Staff

Timeline - History of Television in 22 lots

On May 16, 1949, 40-year-old Milton Berle appeared on the covers of two national magazines: Time and Newsweek, the first time a comedian had graced both titles in the same week. Newsweek ran a photo of Berle sporting a yellow dress, hundreds of colorful beads and a headdress with more fruit than a produce section. Time went a different route, using a lively gouache portrait by magazine illustrator Boris Artzybasheff. Both were perfect in their way. As Time noted in its profile, Berle was just eight months into his run as host of Texaco Star Theater, the nascent medium’s top performer and “a jack-of-all-turns vaudeville comic who has gone into television and won a bright new feather for his very old hat.” There was some grousing about how he was loud, brash and “often tasteless.” But the stodgy Time had to acknowledge he was a genius, too – a man who “uses not only his brash, strongbow-shaped mouth to get off his loud, fast, uneven volley of one-line gags; with expert timing and tireless bounce, he also hurls his whole 6 feet and 191 dieted pounds into every act of his show.” Uncle Miltie, as he called himself, was all-in on television. Anything for a laugh, he said. No, really. Anything.

It’s only fitting for this auction filled with television treasures that we turn to Late Night with David Letterman to explain why Ricky Ricardo loved his guitar. On May 23, 1983, Desi Arnaz joined Letterman to discuss the making and impact of I Love Lucy; he even performed Irving Berlin’s “I’ll See You in Cuba.” But before that, Letterman asked Arnaz – perhaps best known for playing the conga drums on I Love Lucy – which instrument he preferred. Arnaz was quick with his response: guitar. And why? “All Cubans play the guitar and sing,” Arnaz told the host. “You need that – you need it to romance when we serenade.” He then mimed strumming a guitar – this one, perhaps, the Gibson LG1 Sunburst that Comisar acquired from the man himself.

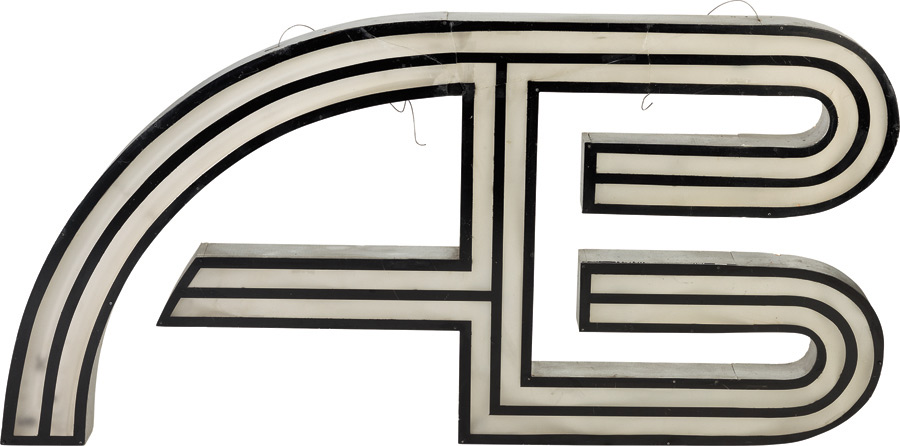

Dick Clark wasn’t there when American Bandstand struck up its first note on Philadelphia television in March 1952, when it debuted as replacement programming. The World’s Oldest Teenager didn’t sign on until July 1956, shortly after which the local show became a national sensation – “the coolest weekly American sock hop to ever air,” as the Los Angeles Times once put it, “where Clark exposed audiences to a nifty little thing called rock ’n’ roll.” The show brought to television the revolution that was beginning to take shape on the radio, featuring R&B acts like the Shirelles and James Brown and the Famous Flames; country musicians including Johnny Cash and Conway Twitty; and Motown artists such as Mary Wells and Smoky Robinson and the Miracles. As Matthew Delmont wrote in his book The Nicest Kids in Town: American Bandstand, Rock ’n’ Roll, and the Struggle for Civil Rights in 1950s Philadelphia, “If American Bandstand helped push Philadelphia Schlock up the charts in this era, it also exposed viewers to a wider range of music than did Top 40 radio.” The sign in this auction, featuring the logo that debuted in the late 1960s and was used throughout the show’s most influential decade, bundles up all that history into a single iconic moment.

The U.S. Marshal badge in this auction looks like most worn by The Law in the 1880s; when the West was wild, a slab of metal almost like this one adorned the chests of men like Wyatt Earp, Pat Garrett, Bat Masterson. And, of course, U.S. Marshal Matt Dillon, the man who kept the peace in Dodge City, Kansas, during all of Gunsmoke’s 635 (!) episodes. In fact, this is the very badge James Arness wore in the show’s opening shot; it says so right there in the handwritten letter from series prop master Clem Widrig, from whom Comisar acquired the significant symbol – not just of law and order in the Wild West, but of TV’s longest-running series until Bart Simpson had a cow, man. So beloved was the show, which ran from 1955 until 1975, that Arness was made an honorary U.S. Marshal, with the service honoring him upon his death in 2011 with a post that said, in part, “We tip our hats to a gentleman who truly got behind law and order in real life.”

Upon her death in 2013, The New York Times wrote of Annette Funicello: “She was the last of the 24 original Mouseketeers chosen for The Mickey Mouse Club, the immensely popular children’s television show that began in 1955, when fewer than two-thirds of households had television sets. Walt Disney personally discovered her at a ballet performance. Before long, she was getting more than 6,000 fan letters a week and was known by just her first name in a manner that later defined celebrities like Cher, Madonna and Prince.” And still she remains the most remembered cast member of the original members of the Club, as immortal as the ears she wore or the theme song they sang (“Who’s the leader of the club that’s made for you and me?”). There might have been bigger stars who followed in (much) later years – Justin Timberlake, Britney Spears, Christina Aguilera, Ryan Gosling – but to TV’s first pop icon goes the credit. And this jacket, which bears Annette’s name inside, is among the most coveted keepsakes from the original American idol.

In the end, the audience knew relatively little about the man who walked through those colored curtains every night for three decades, who turned headlines into one-liners, who sat behind that modest desk and asked only that famous faces make him – and us – laugh before bedtime. Johnny Carson wasn’t there to tell his story (unless joking about a divorce or two), but to provide a seemingly nonstop narrative that often turned calamity into comedy and let us breathe a little easier before the lights dimmed. So modest was the man, befitting his Nebraska upbringing, he didn’t even think anyone would want his desk and set upon his retirement. Carson was said to be stunned (and, likely, a little flattered) when Comisar asked to care for it once he said his final “good night” on May 22, 1992. But even now, that set, with its painting of “beautiful downtown Burbank” and the desk that carried Carson to the finish line during his final decade on television, looks ready to host another few decades of banter and bedtime stories.

When the S.S. Minnow’s three-hour tour turned out to be Gilligan and the Skipper’s last and longest, the boat’s absurdly inadequate life preserver – hopeful with its faded ship name and tattered rope – served as a symbol for the great adventure of seven shipwrecked seagoers that unfolded over three seasons and 98 episodes of Gilligan’s Island. No matter how hard the Professor and the Skipper and the rest tried to rig a way off the island, Gilligan managed to accidentally, and hilariously, scuttle the attempt. In a way, the life preserver epitomizes the great Bob Denver as the perpetually affable and clueless Gilligan: wanting to help but maybe not so helpful. It is an instantly recognizable slice of the show, and here’s a bonus: Painted on the reverse is “S.S. LUVVY” in darker black letters with a silver outline.

There is no shortage of I Dream of Jeannie costumes available on the internet, a few for Halloween but most for the cosplay set in need only of a Major Anthony Nelson and a bottle full of wishes. This ensemble, however, is the real deal – the very (and very pink) three-piece harem costume and head-to-toe accouterments worn by Barbara Eden during Season 1 of the show’s five-season run. And Comisar’s conservator will attest no one took better care of it than he, tracking down missing and matching pieces until it looks today as it did when Sidney Sheldon conceived of and launched the series born as a response to Bewitched. Of course, the costume is best known now for what it didn’t show: Jeannie’s bellybutton. But as Eden long ago explained to the Archive of American Television, the network didn’t care about that until the media fussed over it and producer George Schlatter asked to “premiere Jeannie’s navel” on his Laugh-In. “Well, when he wanted to do that, NBC had a fit – just had a fit,” Eden recounted with a loud laugh. “I don’t think anyone had really taken my bellybutton seriously until [then].”

The Dark Knight has never been darker in recent years, thanks to Frank Miller, Tim Burton, Christopher Nolan, Matt Reeves and every writer, artist and actor who rendered Batman a grim avenger incapable of so much as a grin. This might be why there is no shortage of think pieces and video essays celebrating Adam West as “the best Batman” – because he was the most like the Caped Crusader who appeared in the comics alongside Robin, the Boy Wonder in a yellow cape and green short-shorts. As Comic Book Resources noted just last year, “When Batman dominated TV from 1966 to 1968, the comics-accurate look of many of the characters, as well as the focus on a variety of gadgets and vehicles, helped make the series feel like a Batman comic brought to life.” And, in return, the comics imitated the TV series: The yellow oval synonymous with West’s costume and the Silver Age Batman was born of television’s interest in a Batman series and DC Comics’ need to create an easily copyrighted image. It’s fair to say this Dynamic Duo might be the most recognizable – and coveted – pair of costumes in The Comisar Collection. For the fan, the fetishist or just a night out doing The Batusi.

Comisar’s collection is filled with gems from major moments in television history, chief among them Captain Kirk’s red-and-gold Grecian tunic worn in Star Trek’s third-season episode “Plato’s Stepchildren,” in which William Shatner and Nichelle Nichols’ Lieutenant Uhura shared TV’s first interracial kiss. It’s often pointed out there were others that came before: A full decade earlier, in 1958, Shatner kissed France Nuyen on The Ed Sullivan Show during a scene from the Broadway production of The World of Suzie Wong. But the Kirk-Uhura kiss is the one best remembered, as NBC executives feared it would spark backlash from Southern affiliates. Nichols would later recall but a single letter of complaint, which read, “I am totally opposed to the mixing of the races. However, any time a red-blooded American boy like Captain Kirk gets a beautiful dame in his arms that looks like Uhura, he ain’t gonna fight it.” Here, too, are Kirk and Uhura’s Starfleet-issued tunics, which have never gone out of fashion thanks to the never-ending adventures of the Starship Enterprise on Paramount+.

America was first invited into Archie and Edith Bunker’s living room on January 12, 1971, and for nine seasons, this is where the country assembled for its most difficult conversations – about homosexuality, the war in Vietnam, rape, race, abortion, politics, women’s liberation, menopause. Norman Lear’s adaptation of the BBC series Till Death Us Do Part was as controversial as its UK counterpart. Yet, viewers didn’t refuse the invitation to the Bunkers’ Queens residence: The series rose to the top of the ratings for five years while garnering numerous awards. That this set remains intact is nothing short of miraculous after Comisar retrieved it from a studio warehouse, where it fell into disrepair before its careful conservation. Assembled again in the Heritage offices, complete with the couple’s trademark chairs, it seemingly comes to life: You can almost hear the insults and arguments echoing in the shabby yet sacred space.

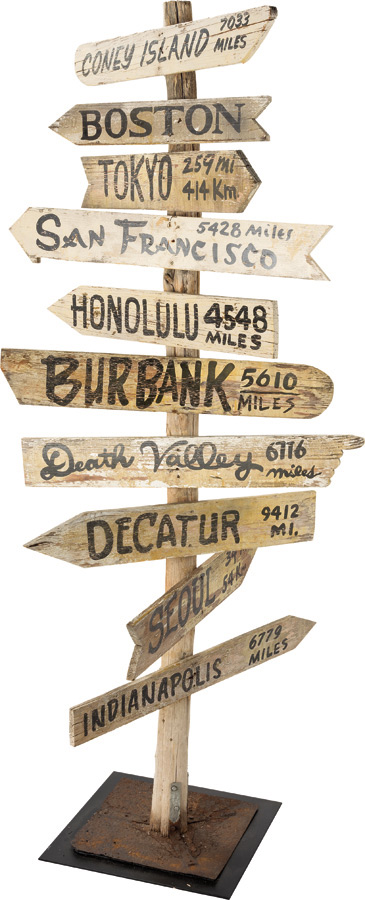

As far as network executives were concerned, CBS’ All in the Family made iconoclasm cool – enough to transform Robert Altman’s rowdy big-screen version of Richard Hooker’s novel M*A*S*H into something acceptable for prime time. It took a full season, followed by a summer’s worth of reruns, to transform the small-screen iteration into a ratings hit. Eventually, it became one of America’s most beloved shows, an anti-war dramedy populated by Hawkeye Pierce, Trapper John, Hot Lips Houlihan, B.J. Hunnicutt and the other immortal meatball surgeons who broke audience’s hearts while wearing an anarchic grin. From that revered series, which ran from 1972 until the most viewed “Goodbye, Farewell and Amen” in TV history in 1983, comes one of its most familiar totems: the signpost adorned with the hometowns of the doctors, nurses and soldiers who staffed the 4077th Mobile Army Surgical Hospital. Three were made for the series: One was destroyed in a fire, one was donated to the Smithsonian Institution, and one is in this auction.

The sweet and hapless clay character Mr. Bill made his national TV debut in 1976 during Saturday Night Live’s first season, and as his adventures unspooled via Super 8 film over five seasons and 20 sketches, it was clear to viewers that the popular character’s fate was sealed. Mr. Bill and his dog Spot, in a loose parody of children’s Claymation shows, were created by SNL writer Walter Williams, who seemed to delight in poor Bill’s torment. Mr. Bill and Spot are put through the wringer in every short; Bill could never defeat his fickle “creator” and co-star, Mr. Hands – who downplays danger in a friendly off-camera voice while inviting chaos into Bill’s otherwise quiet existence – or his clay nemesis Sluggo. Mr. Bill ends up dismembered and crushed in every appearance – as he cries out in his trademark falsetto “Ohhhh nooooo!” – so it was no surprise when his first retirement from SNL in its 1979-80 season depicted him homeless, psychologically traumatized and thrown in prison. The Comisar Collection offers a happy reincarnation of a screen-used Mr. Bill created for the 2001 Mr. Bill Summer Adventures national ad campaign for Ramada Hotels.

When Dynasty premiered on ABC in 1981 as competition for CBS’ Dallas, the show’s ratings were less than impressive. Then Alexis Carrington entered the picture. The glamorous villain played by Joan Collins joined the show in Season 2 and immediately raised the ratings – and temperature – of the nighttime soap opera about a wealthy Denver oil family. Whether she was firing off scathing insults or brawling in a lily pond with archenemy Krystle Carrington, Alexis kept viewers tuning in and helped make the series the No. 1 show in its 1984-85 season, beating out its Texas-based rival in celebrating ’80s excess. This monumental painting of Alexis sporting big hair and even bigger shoulders was commissioned by production so she could always look down on those around her. It was rendered in the palette and style of popular artist of the era LeRoy Neiman, who was known for capturing “the brash, brassy life of conspicuous consumption.”

Of all the items in The Comisar Collection, the bar from Cheers might be the most recognizable. The moment it was assembled in Heritage Auctions’ headquarters – its wood-paneled sides reconnected, its brass railing reaffixed, its barware laid upon the lacquered top – onlookers began congregating in the hopes Sam Malone or Ernie “Coach” Pantusso or Woody Boyd might serve them a beer. They gravitated toward the corner where Norm Peterson held court alongside postman Cliff Clavin. And they looked around for Diane Chambers, Carla Tortelli, Rebecca Howe, Frasier Crane and the other regulars for whom the Boston bar was their home away from everything and anything else during 11 acclaimed seasons. Cheers was almost a workplace comedy presented as theatrical performance; seldom were the episodes that didn’t take place around that bar with those characters who’d become as beloved as family. The namesake wasn’t a real tavern, but from 1982 through 1993, this bar was where America pulled up a stool and nursed a cold one. Following the series’ last call, the bar went to a Hollywood museum that allowed bachelor-party attendees to spill their beers all over these memories. Comisar brought it back to life, and now it can go to your home, where, presumably, everybody knows your name.

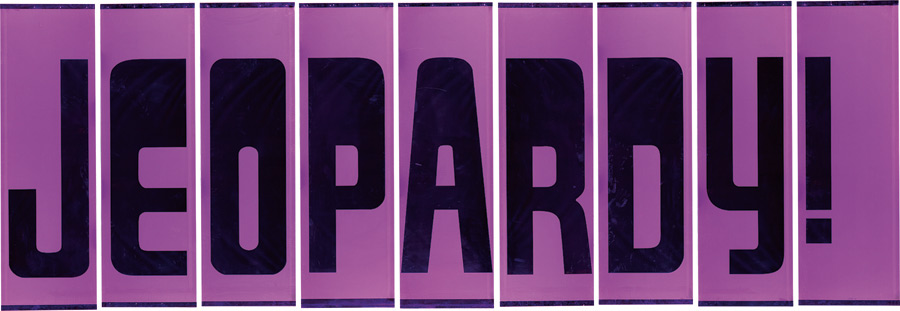

Beginning in September 1984, host Alex Trebek walked through the panels that make up this iconic wall for more than 1,300 tapings of the quiz show that has captured the attention of generations of fans. Created in 1964 by Merv Griffin, JEOPARDY! flipped the traditional game show format by offering contestants the answers and requiring them to ask the questions. Each of these nine wall panels, acquired from Trebek and executive producer Harry Friedman, measures 114 inches tall and more than 35 inches wide. Lined up together, the massive display stretches 27 feet from one end to the other. The panels were retired in 2002 in favor of a newly designed set.

When MTV debuted in 1981, its creators had no idea they were about to revolutionize not only cable television but also the entire music industry – and eventually our conception of what an awards show can be. MTV’s longtime mascot was doctored footage of the moon-landing astronauts in full gear planting an MTV flag on the lunar surface, so in 1984, when the MTV Video Music Awards debuted, the award statuette handed out to winners was a shiny, chromed Moonman. The VMAs were instantly popular and enormously showy and expensive – and often marked by headline-making antics (Kanye West jumping onstage to bumrush award winner Taylor Swift in 2009 comes to mind). These massive Moonman set pieces – printed polyfoam flats for stage right and stage left – flanked the awards stage, and now the monumental symbols of MTV’s golden age can be yours.

Credited with kicking off TV’s obsession with teen dramas, Beverly Hills, 90210 revolved around a crew of privileged students from West Beverly High as they navigated life, love and the rocky road into adulthood. In any given episode, you were likely to find Brenda, Brandon, Kelly, Dylan, Donna and David hanging out at their favorite after-school spot: The Peach Pit, a retro diner run by lovable Nat. But in Season 2, trouble hits the Pit via a karaoke machine Nat thinks will boost business. The gang is not impressed and threatens to boycott their beloved hangout, leading Nat to acquiesce: “Karaoke is great, but The Peach Pit is a juke joint,” he tells Brandon. “Always was, always will be.” This 1969 Wurlitzer jukebox was a fixture in the diner for all 10 seasons of the ’90s pop culture phenomenon.

The red Lycra one-piece donned by bombshell lifeguard C.J. Parker on Baywatch might not have made Pamela Anderson a sex symbol (the actress and model can thank Playboy for that), but the legendary swimsuit certainly solidified her status. Baywatch never wowed the critics (The Hollywood Reporter described its 1989 debut episode as “a pleasant, if unstimulating, way to begin a weekend”), but fans found the show a little more, um, stimulating, especially once Anderson joined the series in 1992. Though C.J. saved lives, fell in love and got mixed up in plenty of other dramas during the character’s stint on the show, it’s the custom-made suit designed to flatter Anderson’s figure that viewers most remember. Well, that, and all the slow-motion running.

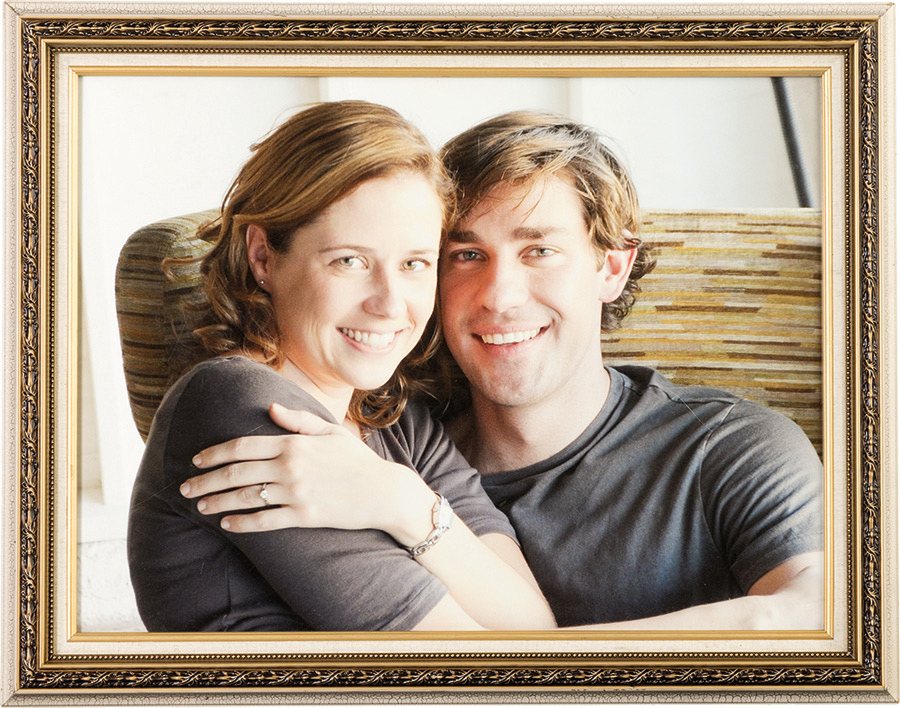

In the end, it wasn’t much of a will-they-or-won’t-they – not quite like Sam and Diane, David and Maddie, Mulder and Scully, Kermit and Miss Piggy. Jenna Fischer’s Pam Beesly and John Krasinski’s Jim Halpert were always going to wind up together, no matter how many couldas (Roy!) and shouldas (Karen? Katy!) they had to slog through to get there. They were co-conspirators in an Office full of dunderheads, a match made in Scranton, love at first smirk and eyeroll. And this portrait of the couple doesn’t get more official: It’s the centerpiece of Pam and Jim’s wedding website, and it later hung in their house – the happy couple in matching gray tees. For once they’re both staring at the camera with sincere smiles and happiness in their hearts.

By 2008, when every home design magazine and website started featuring midcentury-style decor in their photo spreads, there was only one explanation: Mad Men’s entire aesthetic took the nation by storm in the summer of 2007 and has yet to recede. Love him or hate him, the show’s anti-hero Don Draper, along with his hard-drinking work cronies, looked incredible, and so did their sets. The drinking culture at Sterling Cooper & Partners can only be described as epic (cigarette smoke had some real presence, too), and the ad men didn’t abstain once back at their groovy homes. Their whole world was awash in Old Fashioneds and martinis. Fittingly, Comisar has gathered a collection of the fizzy, boozy tools and a cart that were so central to the conversations and inspirations dreamed up by Don, Roger and Co. at the office and at home. You can practically hear Don’s brain clicking into gear to conjure Lucky Strike’s next campaign as he mixes a cocktail in his Park Avenue penthouse. Cheers, Don, and break a leg during tomorrow’s pitch meeting.

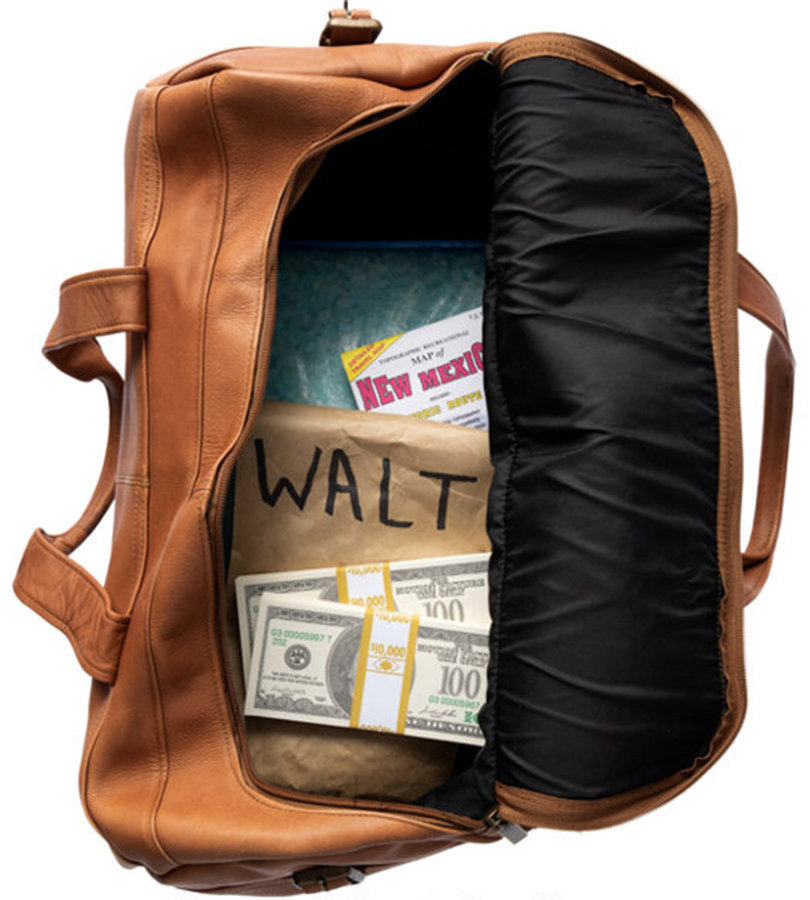

When Vince Gilligan pitched AMC a new show about a chemistry teacher who becomes a meth kingpin, he touted accordingly: “You take Mr. Chips and turn him into Scarface.” And so Walter White was born – before he died, inevitably, felled by the anguish and ambition, grief and greed that transformed a middling nobody diagnosed with cancer into the one who knocks. Fifteen years after its debut (to a paltry 1 million viewers who became a tenfold army come closing time), Breaking Bad remains one of the few genuine masterpieces from the Peak TV period – good enough to spawn a spinoff (Better Call Saul) that might have been better, great enough to withstand a coda (El Camino) that wasn’t all that necessary. This duffel contains a Breaking Bad précis: a brown paper lunch bag marked “WALT,” a road map of New Mexico, Walter and Skyler’s divorce petition, the show’s famous car wash speech and, of course, nearly 5 pounds of blue meth portioned in its original 1-gallon bag by Walter and Jesse for street distribution. The perfect keepsake from the perfect show. Yeah, science.