COLLECTORS ARE CLAMORING FOR WORKS BY THE ATHLETE TURNED ARTIST WHOSE PAINTINGS HAVE GRACED ALBUM COVERS, OLYMPICS POSTERS AND ONE GROUNDBREAKING TELEVISION SHOW

By Christina Rees

The works of American painter Ernie Barnes are experiencing a comeback like that of no other artist of the last decade.

Barnes’ circa-1989 painting Quintet – a highlight of Heritage Auctions’ May 12 Diverse Visions: Important Works by American Masters Signature® Auction – is among the most recognizable pieces by the former pro footballer who was once fined by the Denver Broncos’ head coach for sketching during team meetings. Barnes, perhaps best known for his painting The Sugar Shack, used in the credits of the TV show Good Times and on the cover of Marvin Gaye’s 1976 album I Want You, is one of the 20th century’s most distinctive painters. Last year, The Sugar Shack sold at auction for $15.3 million – 76 times its high estimate of $200,000.

“Almost like a more modern Thomas Hart Benton or El Greco,” says Aviva Lehmann, Heritage’s Senior Vice President of American Art. “His works are lyrical, as close to dancing as a painting can get. And Quintet is among the most intimate masterworks of his entire oeuvre.”

Quintet was exhibited in the fall of 1990 at New York’s Grand Central Art Galleries as part of Barnes’ solo exhibition The Beauty of the Ghetto, which was subtitled Exhibition of Neo-Mannerist Paintings – and that “neo-mannerist” is apropos, given that a hallmark of Barnes’ work is how elongated and fluid his human figures are; Barnes’ background as an athlete granted him a breathtaking interpretation of bodies in motion. And Quintet ranks among Barnes’ masterworks, a joyful depiction of jazz musicians at work and at play, a piece so alive it echoes with a bebop soundtrack. Their eyes are closed – a hallmark of Barnes’ work that dates back to 1971, when he said he first conceived of The Beauty of the Ghetto as an exhibition.

“I began to see, observe, how blind we are to one another’s humanity,” Barnes said at the time. “We don’t see into the depths of our interconnection. The gifts, the strength and potential within other human beings.”

Barnes has long been acknowledged as a master by musicians who often used his works as album covers, among them Curtis Mayfield, B.B. King and Gaye. His lithe, ecstatic works look almost like sheet music – figures like notes dancing across the staff. Which should come as no surprise: Barnes’ father played piano in the family’s Durham, North Carolina, home, and Barnes was so influenced by Dad he framed each painting in distressed wood as a tribute: “Daddy’s fence,” he once said, “would hug all my paintings in a prestigious New York gallery.”

DIVERSE VISIONS: IMPORTANT WORKS BY AMERICAN MASTERS SIGNATURE® AUCTION 8113

May 12, 2023

Online: HA.com/8113a

INQUIRIES

Aviva Lehmann

212.486.3530

AvivaL@HA.com

The painter was also raised listening to church choirs. Listen closely. Quintet, much like The Sugar Shack, roars and reverberates like the long Saturday night before Sunday-morning services. The painting brings the viewer directly into the fold of five musicians who are in deep connection with the music and one another; the viewer is not only in the room with the protagonists but also sitting right inside this tight circle of players who lean in as they hit a long, blue note. The jazz club’s close darkness is filled up by the men, punctuated and delineated by the musicians’ strong diagonal physicality and their burnished and gleaming instruments: piano, two saxophones, a stand-up bass and a trumpet. The pianist’s torso sways back from the center, his elegant fingers poised mid-note. There is a delicious tension and harmony between the men, that intimacy of shared flow, as they move through the music. Barnes’ golds, black and browns evoke the weight of centuries of painting even as he updates action and venue: Here the gathered gods wield brass and strings instead of scepters, and the dusty old Roman plaza gives way to a smoky and celebratory 20th-century Harlem. When the art world talks about updating the canon, it could not do better than Quintet.

Barnes was born in Durham in 1938. His mother oversaw the household staff of a lawyer, and his father was a tobacco company clerk. Barnes was drawing and painting from a young age, but his athletic scholarship took him to North Carolina College of Durham (now North Carolina Central University), and all along, the physicality of his world – the way bodies merge, move, interact and dissolve into one another – has informed his pictures. As often as he painted solo figures, Barnes’ showstoppers (like The Sugar Shack and Quintet) often feature groups of people in shared and responsive motion.

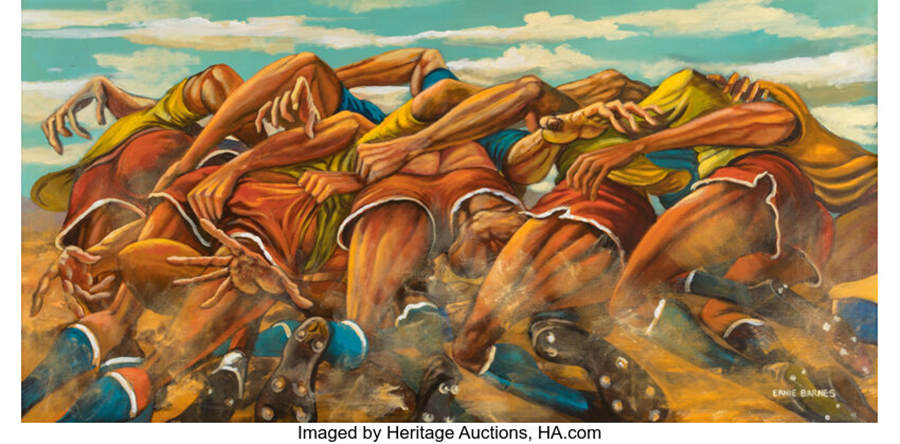

In fact, Heritage’s May 12 auction offers another significant Barnes work – Scrum, 1980, which depicts exactly what the word describes: a mass of faceless rugby players locked together through sheer muscular force. Through the dust kicked up by their cleats, a forest of thigh muscles heave in sinewy explosion; expressive hands grasp, dig and push. The perspective puts the viewer so close to the action that you can hear the men’s grunts and smell the sweat. It is a tour de force of Barnes’ incisive take on bodies working in unison and in tension. By the 1980s the artist was known for this territory and was asked to create five official posters for the 1984 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles.

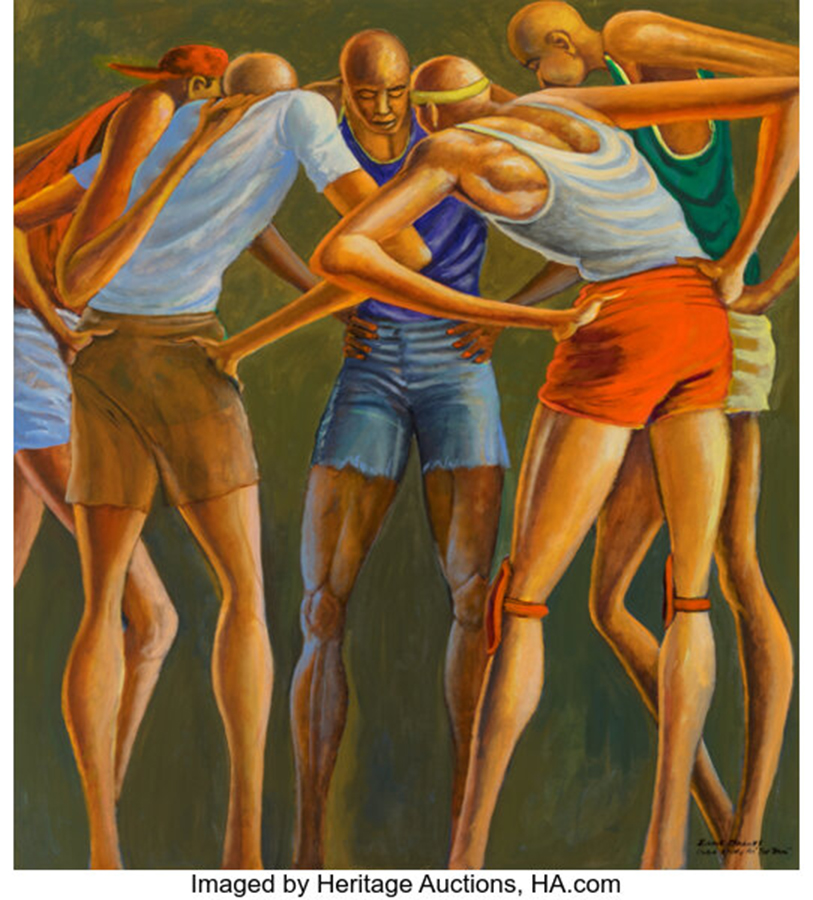

In this vein, Heritage also offers a study of Barnes’ The Team, which takes us right up to a circle of men discussing their next play. The amateur athletes in this picture – all with bowed heads and closed eyes – present a vertical stack of long limbs, broad shoulders and smooth heads. Here they confer with one another in a relaxed and smiling moment, a pause of conjoined focus, just before springing back into electrified action.

Barnes died in 2009, but by then his aesthetic was already deeply woven into the American psyche; his presence in popular culture had been radiating outward and resonating through countless imitations of his indelible style. You cannot see a Barnes work without placing it at the center of an era we still look to for ballast in these unsteady times. Barnes’ vision of Americans surviving and thriving via community and celebration has claimed (if not reclaimed) its top spot in our understanding of how much art can show us what we most need to truly live, what we most value in ourselves and each other, which is presence. We are fundamentally social animals, and like it or not, we are woven together. Barnes was deeply committed to focusing on the Black experience in all its richness and variety, and his angle observes and honors people going about their daily (and nightly) business while fully engaged in the very evolution of American culture.

As Barnes once said: “I am bound by the strongest ties with the organic life of all people. And being an artist had created in me the desire to continually affirm beauty. I am well aware that art has no concrete connection to beauty, but beauty is profoundly interwoven into the fabric of the individual and his environment.”

CHRISTINA REES is a staff writer at Intelligent Collector.

CHRISTINA REES is a staff writer at Intelligent Collector.