DISNEY ARTIST AND SON WORKED ON SOME OF HOLLYWOOD’S GREATEST FILMS

By Steffan Chirazi

Before CGI and technology became the standard in cinematic special effects, Peter Ellenshaw and Disney Studios were the brilliant visionary vanguards and purveyors of cinematic illusion. Ellenshaw is widely recognized as one of the greatest matte painters in Hollywood history, his natural artistic gifts manifesting themselves in son Harrison Ellenshaw and daughter Lynda Ellenshaw Thompson, who also became titans in the respective fields of matte painting and visual effects.

EVENT

ANIMATION ART SIGNATURE® AUCTION 7235

Featuring the Ellenshaw Collection

Dec. 11-13, 2020

Dallas

Online: HA.com/7235a

INQUIRIES

Stephen Wetzel

214.409.1653

StephenW@HA.com

Jim Lentz

214.409.1991

JimL@HA.com

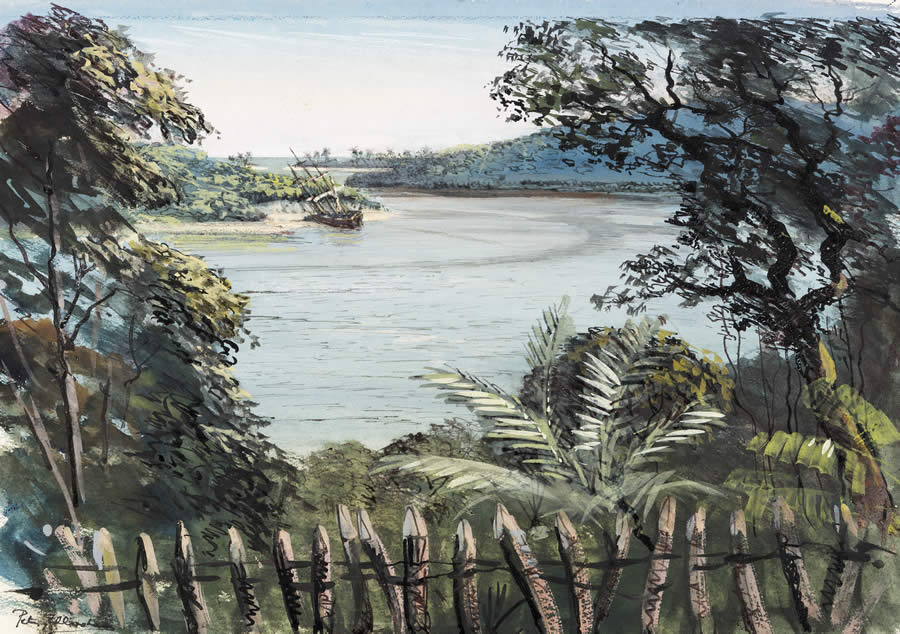

Inspired by the work of J.M.W.Turner, and Peter’s step-father, the effects film legend Walter Percy Day, Peter created iconic, magical work with Disney, winning the Best Visual Effects Oscar in 1965 for Mary Poppins, and building a canon of spectacular credits in films such as 20,000 Leagues Under The Sea, Darby O’Gill and the Little People, Bedknobs and Broomsticks, as well as Disney’s first live-action film, 1950’s Treasure Island. Peter was also a noted landscape and marine artist, as evidenced by pieces such as “Wood’s Cove” and “Ships in Falmouth Harbor.” He passed away in 2007.

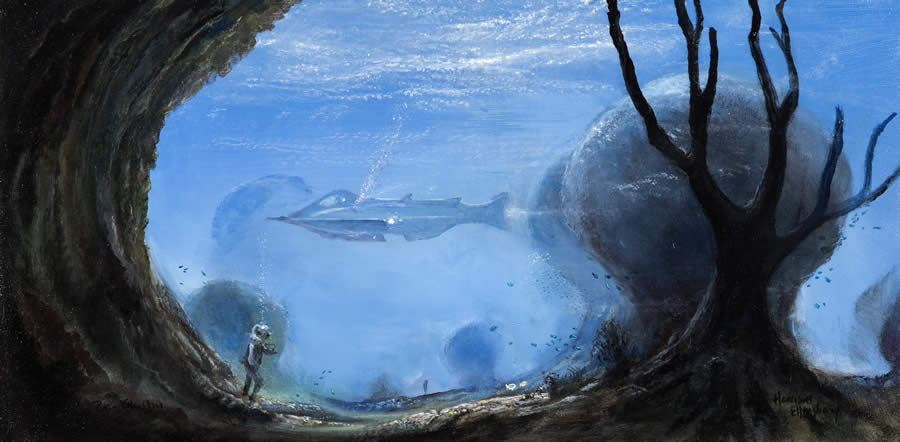

Harrison achieved fame in his own right thanks to 1977’s Star Wars and 1980’s The Empire Strikes Back, as well as becoming the head of Disney’s special effects department, Buena Vista Visual Effects (BVVE).

“I miss my father,” Harrison says warmly one weekday afternoon from his Southern Californian home. “I look back at his art now and it’s magnificent. We had a special relationship because we both ended up in the same business, and sometimes that made it a little competitive. I think for us, the turning point was probably Star Wars because before that, my father had Mary Poppins, 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, Darby O’Gill and the Little People and all those other movies, but with Star Wars I went into the same league.”

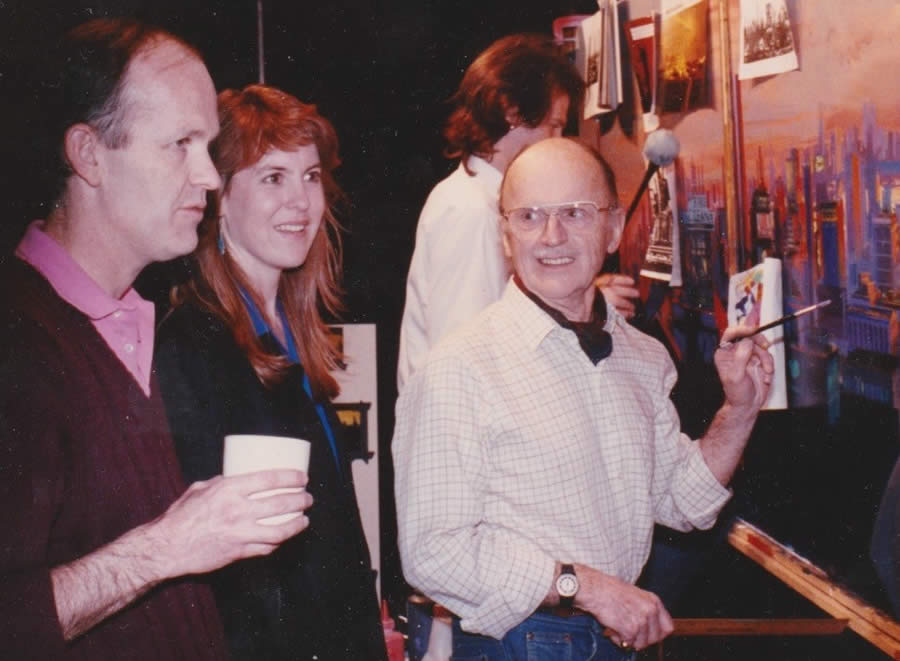

Harrison now is offering 100 pieces from The Ellenshaw Collection to fans worldwide at Heritage Auctions’ animation art auction scheduled for Dec. 11-13. “This is the very first time the Ellenshaw Family Archives have ever been opened for sale to the public,” says Stephen Wetzel from Heritage Auctions. “Some of the artwork from these films is coming to market for the first time, and there are pieces from the personal Ellenshaw art collection that are also new to market.”

Enlarge

“Lynda and I,” Harrison adds, “both came to the same conclusion, that we will never have a place big enough to exhibit everything and artwork like this needs to be out hanging somewhere for others to appreciate, to have an opinion about, and to enjoy.”

When you see the concept piece Treasure Island, what thoughts do you have?

That my father understood how to tell a story, or a shot, by making a sketch, and Walt Disney loved that kind of stuff. Walt didn’t want to go on location. Treasure Island was shooting in England, so OK, let’s have Peter Ellenshaw make the English seaside look like the Caribbean.

How about something like [the painting titled] 3rd Hole at Mauna Kea, Hawaii?

My father did not play golf, but there’s a beauty to golf courses that my father enjoyed. He loved going to Hawaii because it was so beautiful, so he began to paint golf courses. I will reveal a story nobody’s ever heard before. … Somebody asked my father to do a commission for the owners of Loch Lomond [Golf Club in Scotland]. He did a piece for the clubhouse and the owner’s wife said, “No, I don’t like that.” And so my father, who did not take kindly to people without artistic background criticizing a commission, said, “Too bad!” She came back and said they weren’t going to pay because it needed to be the certain way she wanted it. He said he didn’t care. So I painted it! We got the money, everybody was happy. And the good thing was that we got to keep the original painting that he had done.”

Enlarge

Ships in Falmouth Harbor, England, Original Painting, 1977

Estimate: $5,000-$7,500

Enlarge

3rd Hole at Mauna Kea, Hawaii, Original Painting, 1994

Estimate: $5,000-$7,500

Let’s talk about one of your pieces now, Alice in Wonderland: Floating in Wonderland, an original interpretative art piece. What does it mean to you?

Alice in Wonderland was always one of my favorites. I love the concept of falling into the rabbit hole and chasing the White Rabbit. And so I tried to incorporate, as I do in a lot of pieces, that universal memory trigger which makes the relatability so strong. We all want to follow the White Rabbit, and then we get down in there, we have to deal with the craziness.

Enlarge

Enlarge

When working on a matte painting, say for Star Wars, are you feeling the film or are you feeling the directive of the scene that you have to paint as a piece of standalone art?

You constantly have to step back, look at what you’re doing, and remember the purpose of the shot. It may be as simple as getting from the previous shot to the next shot, and if it doesn’t progress the story or give more information to the viewer, then drop it. Always keep in mind, ‘Why am I painting this?’ And George [Lucas] had an unfortunate habit of not telling you. On Star Wars, I was looking at the plate for the Millennium Falcon and it was called “The Pirate Ship.” They built half the set in London, So I painted in the other side to make it look like a “dual cockpit” with a left side cockpit and a right side cockpit. Showed it in dailies and everybody laughed. George said, “Did you look at the model?” I said no, I work at night, things are locked up. So he said, “Go look at the model.” He learned that you’ve got to tell the effects people what we’re doing here. That’s why Empire Strikes Back is so great, because we were all part of a dream team. Communication is key.

Finally, would you agree that matte art has analog warmth versus the cool clinical accuracy of digital art?

They [digital pieces] are sterile. They don’t have the human touch. I had been around my father, seen him mix colors and it was still a magic trick. He could just go, “Here, here, here,” and it matched perfectly, which of course became the real challenge with matte paintings. It took me four or five years to get to the point that I could just do that automatically.

Enlarge

Cinderella's Grand Arrival Original Art, circa 2000s

Estimate: $1,500-$2,000

STEFFAN CHIRAZI is a Bay Area author and freelance writer whose work has appeared in a variety of international publications, including the Metallica Club’s So What! magazine, the San Francisco Chronicle and Kerrang!

STEFFAN CHIRAZI is a Bay Area author and freelance writer whose work has appeared in a variety of international publications, including the Metallica Club’s So What! magazine, the San Francisco Chronicle and Kerrang!

This article appears in the Winter 2020-2021 edition of The Intelligent Collector magazine. Click here to subscribe to the print edition.