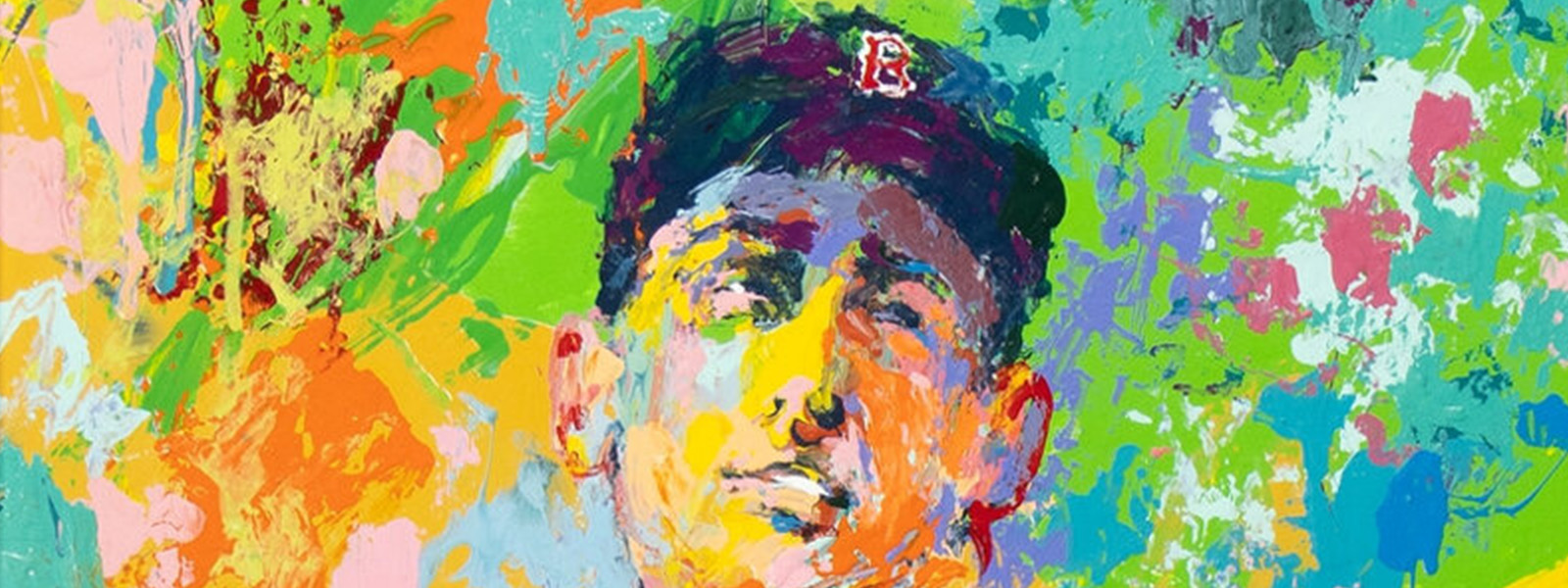

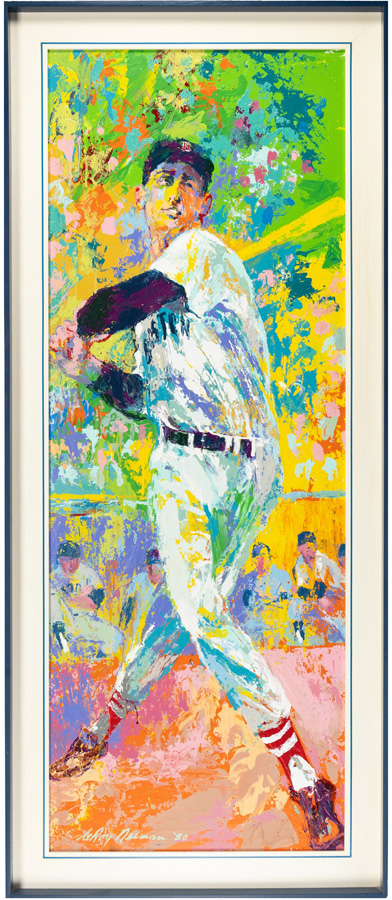

COMPLETED IN 1980, THE COLORFUL PORTRAIT CAPTURES ‘THE SPLENDID SPLINTER’ AT THE PLATE

By Robert Wilonsky

Titled ‘Mr. 400’ and measuring 48 x 18 inches, the painting of Ted Williams that Mike Winter commissioned from LeRoy Neiman is available in Heritage’s February 24-25 Winter Platinum Night Sports Auction.

Mike Winter, a Chicago native, saw Ted Williams play ball only a handful of times – including once at the 1950 All-Star Game at Comiskey Park, where Williams famously fractured his left elbow after smashing into the scoreboard to deny Ralph Kiner an extra-base hit. Williams stayed in the game until the ninth inning of the 14-inning thriller. X-rays found the fracture only after Williams returned to Boston. As the Society for American Baseball Research later noted, Williams would “miss the next 66 games for the fourth-place Red Sox, effectively ending their pennant hopes.”

For Winter, that fearless performance, one among so many he couldn’t keep track, was proof that Williams was the right hero to root for, even from a distance. Almost everything he knew about Williams he’d read in newspaper recaps and box scores; sometimes, he’d catch a few innings on the radio, too. But this kid from Chicago adored the slugger from Boston. Forever and always.

“He caught me,” Winter says now. “He was something.”

Winter was so enamored of Williams that decades later, in the late 1970s, he commissioned LeRoy Neiman to paint a portrait of “The Splendid Splinter” – which was no easy task.

While Winter was still a kid, Neiman was already working for Playboy, where, in 1955, he created the Femlin character who galivanted across the Party Jokes pages. Neiman was painting exotic locales for his “Man at His Leisure” feature and by the 1960s had become the sporting world’s most in-demand chronicler, creating those iconic Technicolor moments from the Olympics, Wimbledon, the Super Bowl, the Kentucky Derby – anywhere the biggest grappled with the best.

In the late 1970s, when he first saw some of Neiman’s creations, Winter worked as a software developer at a major Chicago-based consulting firm. And, he says now, “I was immediately struck by them,” so much so Winter bought a print of a Wilt Chamberlain and Bill Russell painting, which he still has. But Winter wanted something more meaningful, at least to him, so he checked to see if Neiman had ever painted his childhood hero, Ted Williams. He had not.

So Winter, like Williams, swung for the fences: He wrote Neiman and asked him to right that wrong, which he did. It just took a couple of years and a stack of postcards and letters. But in the end, Winter got his painting of Ted Williams – and a hell of a lot more.

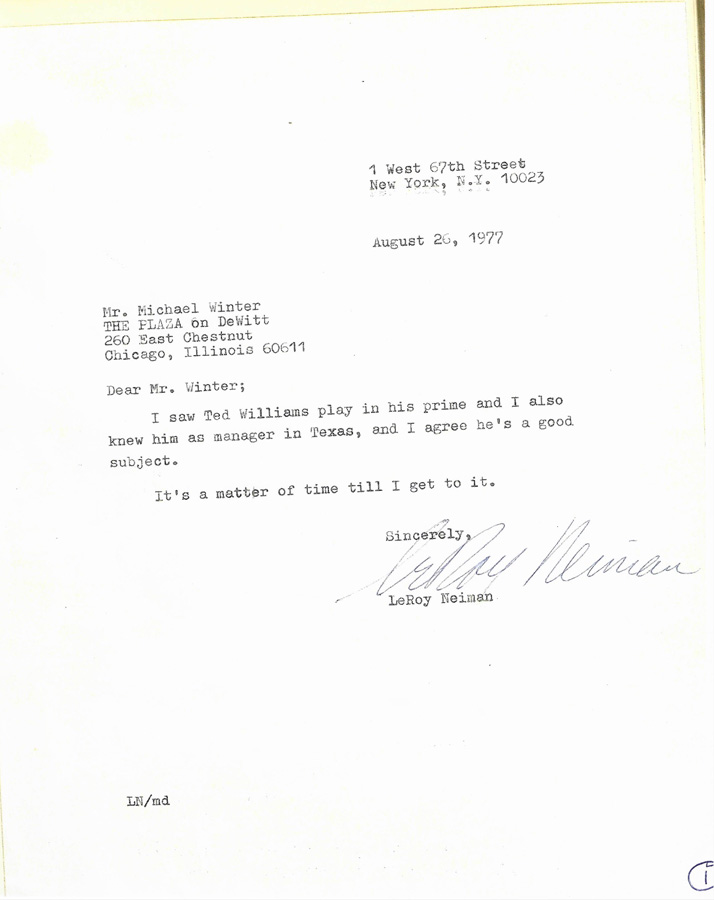

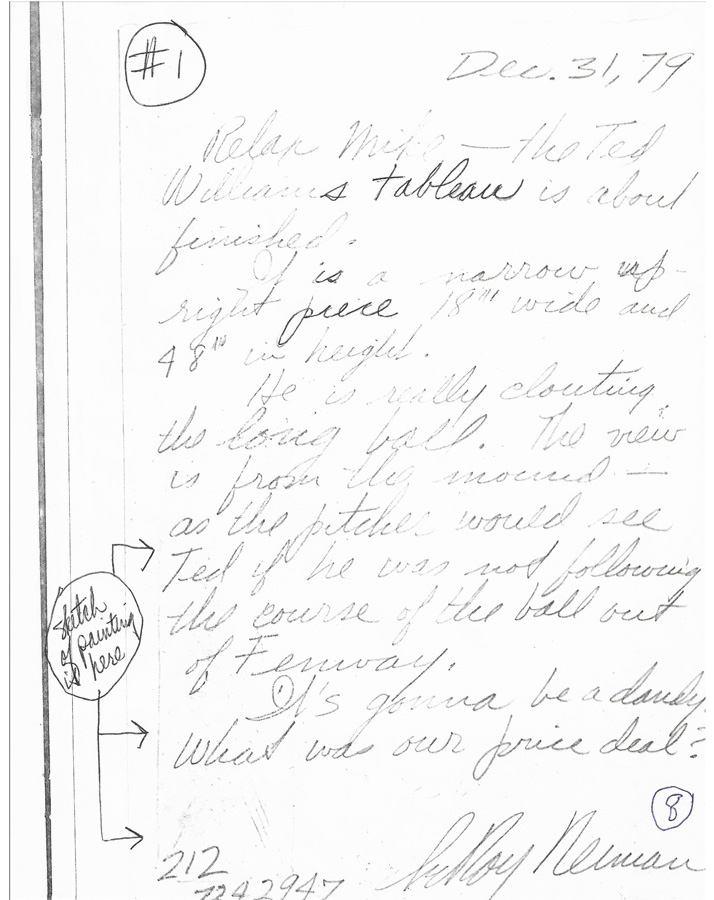

A sampling of the letters Neiman wrote to Winter during their two-year correspondence about the Williams painting.

Winter initially called the Art Institute of Chicago, where Neiman studied following his stint as a cook and then an artist in the Army during World War II. Someone at the Art Institute gave Winter Neiman’s New York address, and in 1977, Winter inquired about commissioning a painting of the man called “The Kid.”

Neiman responded on August 26, 1977, with a brief typed letter: “I saw Ted Williams play in his prime and I also knew him as a manager in Texas, and I agree he’s a good subject. It’s only a matter of time till I get to it.”

Winter was stunned and delighted by the response: “I was surprised he wrote back because I didn’t know what to expect,” he says.

Thus began their lengthy correspondence, which lasted more than two years. Once, in November 1978, Neiman sent Winter a postcard featuring his painting of Willie Mays, upon which he wrote, “A Ted Williams painting is not out of the question.” He said he might even “do a serigraph of it too.”

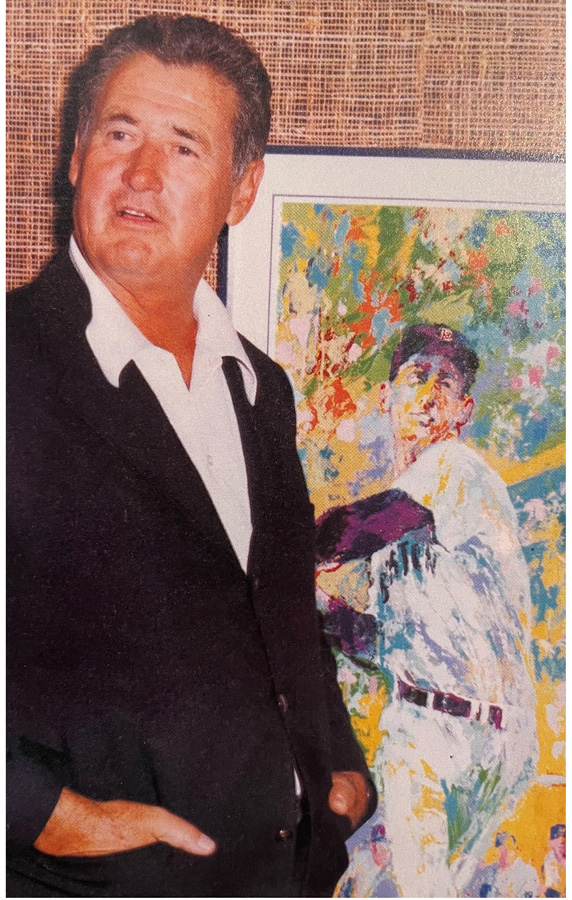

This photo of Williams with the painting appears in Neiman’s book ‘Winners: My Thirty Years in Sports.’

Winter began tracking down photos of Williams from which Neiman might draw inspiration. He waited. And waited. The process was slow, partly because Neiman was in such demand during the late 1970s. By the winter of 1979, Winter was getting anxious and growing concerned his long-imagined painting of Williams might forever reside in his imagination.

“Relax Mike – the Ted Williams tableau is about finished,” Neiman wrote on New Year’s Eve 1979, to Winter’s great delight. “He is really clouting the long ball. The view is from the mound – as the pitcher would see Ted if he was not following the course of the ball out of Fenway. It’s gonna be a dandy.”

Shortly after, Neiman invited Winter to his 67th Street studio in Manhattan to see the painting. Winter brought a friend, Larry Costin, “a basketball teammate of mine and a bona fide art expert,” Winter says. Neiman said he first wanted them to see a different painting leaning against a wall with its back facing front. Neiman flipped it over to reveal Ted Williams, standing about 4 feet tall and looking larger than life.

“On the airplane to New York, I said to myself, well, if I don’t like it, I won’t buy it,” Winter says, laughing. “But when I got there and he showed it to me, I thought it was a wonderful painting. I thought it was just great. It captured Ted.” Upon his return to Chicago, Winter wrote to tell Neiman the painting was “perfect.”

On the back of the painting, the artist wrote, “Ted Williams painted special for Mike Winter,” accompanied by his iconic signature and “New York 80.” In time, it would be joined by another signature – that of the painting’s subject.

Neiman signed and dated the back of the painting and wrote a note to the man who helped make it happen.

In the spring of 1980, Winter saw that Williams was coming to town to collect an award and appear at a local Sears, for whom Williams had long been employed as a “working consultant” – meaning, he helped Sears pick out sporting goods and gave them his stamp of approval. Winter reached out to someone at Sears so they could let Williams know he had a LeRoy Neiman painting of him he might want to see while in town.

“I was persistent,” Winter says. “That was the thrill of my life, doing this stuff.”

The Sears guy told him, well, sure, he’d see what he could do, but no promises because “you can’t really tell Ted Williams what to do.” Then Winter got a phone call.

“And there was Ted Williams,” Winter says, “in my lobby.”

Winter spent three hours with “The Splendid Splinter,” who came over to see the painting and visited with his biggest fan over a few glasses of Jack Daniel’s. Photos from that visit wound up in the books Ted Williams: A Tribute and Neiman’s Winners: My Thirty Years in Sports.

“It was a thrill,” Winter says of his meeting with Williams. “Ted was a very nice guy and quite intelligent. His first question was ‘Why would someone from Chicago do this? I would think it would be someone from Boston.’”

Before he left, Williams added his signature to the back of the painting: “To Mike Winter, One of my greatest fans, Best always, Ted Williams, 1980.”

Williams signs the back of his namesake painting while Winter looks on.

In the end, Neiman never did create a serigraph from the painting. But the Polaroid Corp. made more than 1,000 half-size copies of the work, titled Mr. .400, which generated $1 million for the Jimmy Fund at Boston’s Dana-Farber Cancer Institute. Williams, who spent decades visiting children being treated for cancer, had been the charity’s most vocal and visible supporter since the 1940s.

Winter has displayed Neiman’s original across from his favorite chair for decades, so he can always see the work he willed into existence.

“But now it’s time for someone else to enjoy it the way I have,” Winter says of his beloved Ted Williams painting. “I helped make this thing, and now” – he pauses, laughs a little – “maybe someone in Boston wants to take their turn with it.”

Go here for a closer look at LeRoy Neiman’s Mr. 400, now open for bidding in Heritage’s February 24-25 Winter Platinum Night Sports Auction.

ROBERT WILONSKY is a staff writer at Intelligent Collector.

ROBERT WILONSKY is a staff writer at Intelligent Collector.