‘SIMPSONS’ ANIMATION DIRECTOR WES ARCHER OPENS HIS PERSONAL COLLECTION OF PRODUCTION CELS AND DRAWINGS FEATURING TV’S FAVORITE DYSFUNCTIONAL FAMILY

By Eric Celeste

It’s at the 2:17 mark where you first see it. In Wesley “Wes” Archer’s 1985 full-throttle short animation film Jac Mac & Rad Boy Go!, a trucker blocks the path of the aforementioned partying duo Jac Mac and Rad Boy. He spits out his gum – and his entire mouth twists on his face when he does so.

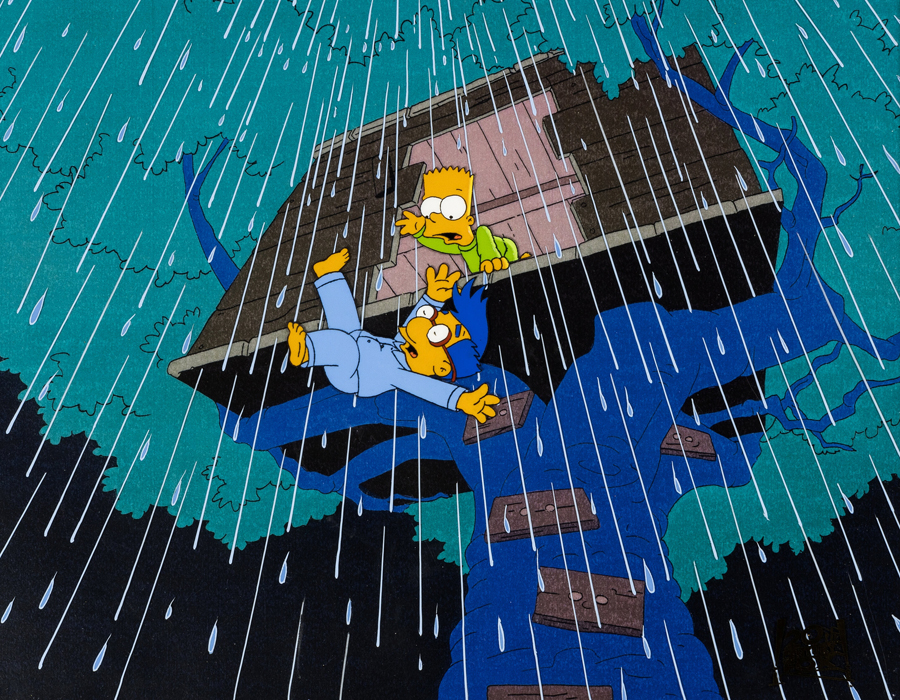

Right there is the first glimpse of a Simpsons moment. As one of the first three animators on the iconic TV show – dating back to its origin as a series of shorts on The Tracey Ullman Show in 1987 – Archer’s early work caught the eye of the Simpsons creators. You can see why – even that four-minute short has an energy, wit and vitality that closely resemble what you’d see in the 26 episodes that Archer directed from 1989-1996. Like with the twisty mouth, when Bart’s mouth would move to the side of his face. We’ve now seen it so much we’ve forgotten how that style (and sensibility, and writing, and insight, and timing, and humor) changed the TV landscape.

If you haven’t rewatched your favorite episodes from the iconic first several seasons – and if you haven’t, please ask yourself why you hate laughter – you could simply revisit a sampling of episodes Archer directed from his favorite seasons (which he identifies as seasons 2, 5, 6 and 7). Or you could use this guide to my three favorite Archer-directed episodes:

- S2, “Three Men and a Comic Book”: Bart, Milhouse and Martin buy the first issue of Radioactive Man, then fight over who can keep it. (Homer: “A hundred bucks?! For a comic book! Who drew it, Micha-ma-langelo?”)

- S7, “Bart Sells His Soul”: Bart sells his soul to Milhouse for $5. His dog stops playing with him, automatic doors won’t open for him, and he can no longer laugh. (When Lisa tells Bart that Pablo Neruda says laughter is the language of the soul, he replies, “I am familiar with the works of Pablo Neruda.”)

- S6, “Itchy & Scratchy Land”: Bart and Lisa persuade their parents to take them on a vacation to an amusement park that bills itself “The violentest place on earth!” (Marge: “This truly was the best vacation ever. Now let us never speak of it again.”)

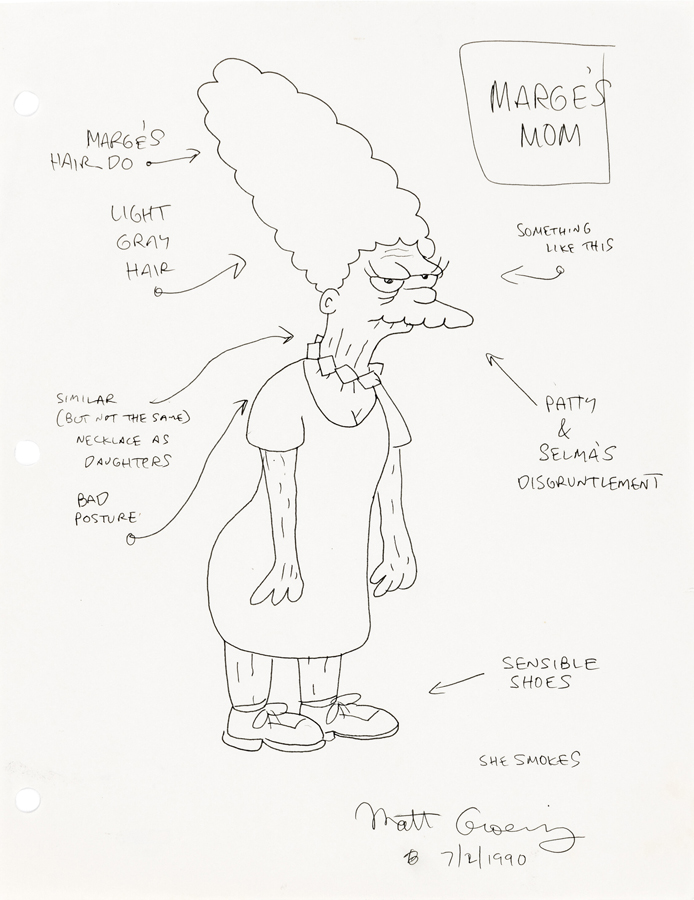

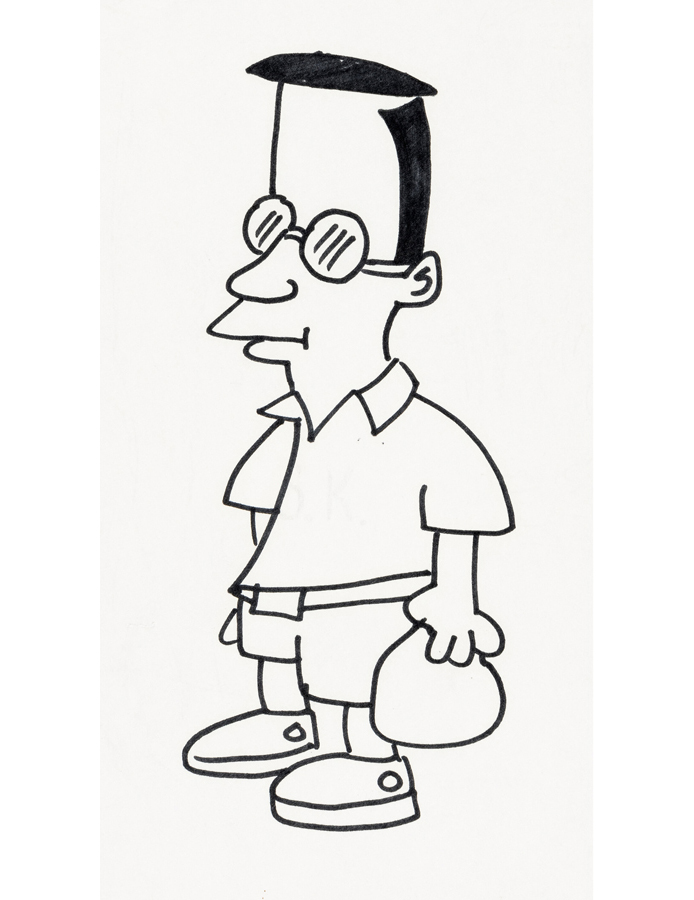

In Heritage’s October 20-23 The Art of Anime and Everything Cool Volume IV Signature® Auction, you’ll find cels from some of these iconic episodes (“Three Men and a Comic Book”) and others (“Lady Bouvier’s Lover”), as well as early sketches by Simpsons creator Matt Groening that give you a sense of how characters such as Milhouse and Marge’s mom developed. The works hail from the personal collection of Wes Archer, who went on to work on other cultural touchstones (King of the Hill, Rick and Morty).

THE ART OF ANIME AND EVERYTHING COOL VOLUME IV SIGNATURE® AUCTION 7311

October 20-23, 2023

Online: HA.com/7311

INQUIRIES

Jim Lentz

214.409.1991

JimL@HA.com

Below, Archer talks about his collection, the series and why The Simpsons made him feel like “the luckiest animation director in the world.”

Why have you chosen to consign these particular items? And which ones are the most special to you?

These items are ones that deserve a place with collectors who will preserve and enjoy them. The “Simpsons Xmas” cels are two of my most memorable cel setups that remind me of those early years figuring out how to draw the Simpson family.

As one of the three original Simpsons animators, did you know that early on that this was special in some way?

Even though its beginnings were somewhat rushed and crude, I definitely had faith that this was the kind of TV animation for our generation and that it could be developed into something substantial.

On some of the Simpsons episodes, you are listed as the director, and on some of those you are additionally listed as storyboarder. Can you explain the differences? What are the unique challenges of each role?

To be an animation director, one must develop and know the art of storyboarding. Sometimes, when a director is idle, the studio will assign them to another director’s episode to help out on the boards in progress. That can be a welcome assignment for stepping away from directing for two or three weeks. Directors in TV animation will often rotate in and out of the storyboard department.

What do you find people remember most fondly from those early years?

I find that viewers and fans will remember specific jokes and tie them into specific stories better than I can at times. Because I’ve directed so many hours of television now, it is impossible to keep track of it all.

“Bart Sells His Soul” is, to me, the pinnacle of the art form. It was always a story about bonds, about a town that worships, about the idea that no bad actor will go unpunished. Is this just overthinking in a Monday morning quarterbacking sort of way, or did those sorts of conversations occur at the time?

The writers on the classic episodes turned in such consistently well-written stories that I felt like the luckiest animation director in the world. And I think I truly was. These kinds of stories did not stray too far from a cohesive theme that had strong threads intertwined in ways that were not too obvious, and in ways that surprised viewers with intelligence as well as heartfelt emotional recognition. They touched upon common agreements and disagreements that we had with the world as a society.

Talk about the speed at which you had to work: 20-something shows a season, every season, working with animators and writers and actors and the network, but also often needing to add elements like musical numbers or guest stars. Can you describe the chaos?

There’s a lot of overlapping episodes, yet they are staggered in the production schedule so that we usually don’t have too much going on at once. We often work with some temporary dialogue tracks that are not the final voice acting, for example, which eases the demands for writers and actors. Music can come in later as well, so that the storyboards kind of get a head start.

What lessons did you take from The Simpsons to your following series like King of the Hill?

It’s a different style and sensibility, but I learned to try to economize and delegate in ways that make the animation better when I began supervising at King of the Hill. Supervising has some producing elements as well as creative directing time.

ERIC CELESTE is a contributor to Intelligent Collector.