FOR MORE THAN 60 YEARS, STAN LEE HAS STOOD AS ONE OF THE MOST IMPORTANT FIGURES IN POPULAR CULTURE

Editor’s note: This story originally appeared in the Fall 2008 edition of The Intelligent Collector. Stan Lee passed away on Nov. 12, 2018.

Interview by Hector Cantú

Like Walt Disney and George Lucas, Stan Lee has created some of the most iconic characters in pop culture: Spider-Man, X-Men, the Fantastic Four, Iron Man, and the Incredible Hulk. Movie’s based on his super-characters have generated more than $2.3 billion in U.S. ticket sales. Toys, books and games have generated billions more.

Lee, simply, is one of the most important figures in American popular culture.

“Working with a team of virtuoso illustrators, many of them idiosyncratic square pegs in the round holes of a simpleminded children’s entertainment medium, Lee unleashed a legion of characters that rank among the most enduring fantasy icons in a cultural landscape soaked with imaginative contenders,” Jordan Raphael and Tom Spurgeon write in their biography Stan Lee and the Rise and Fall of the American Comic Book (Chicago Review Press, 2003).

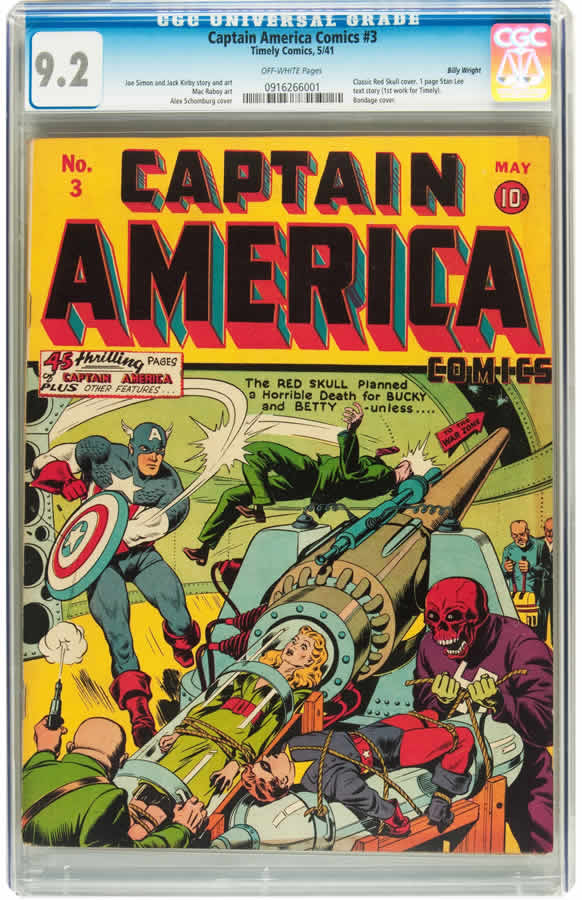

Lee began working for Marvel (then Timely) Comics in 1939, one year after Superman debuted in Action Comics No. 1. Lee’s first published work – a short story titled “Captain America Foils the Traitor’s Revenge” – appeared in Captain America Comics #3 in May 1941. The following year, at age 20, Lee was editor and chief writer, creating stories for a variety of romance, horror, humor, science-fiction and suspense comics.

By 1960, competitor DC comics had launched a team of superheroes called the Justice League of America.

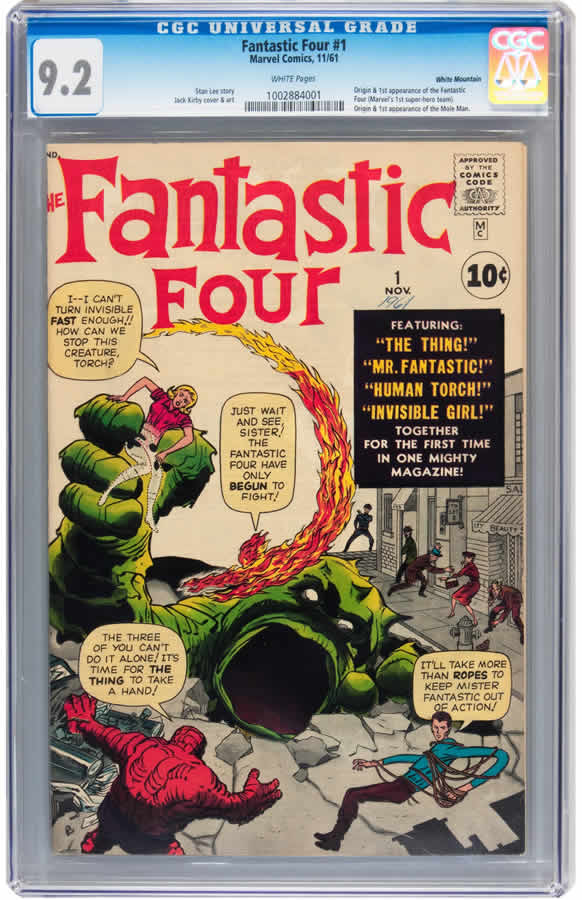

Marvel publisher Martin Goodman demanded a response, and in 1961, Lee and illustrator Jack Kirby produced Fantastic Four No. 1. Fan response was phenomenal, with critics today calling the work a masterful step forward in comic-book evolution. “Nearly all modern superhero comics have drawn and continue to draw on the first 80 or so issues of the Fantastic Four for inspiration and material,” comics historian Robert Harvey writes in The Art of the Comic Book (University Press of Mississippi, 1996).

Lee would continue creating characters for Marvel over the next two decades. Along the way, he would produce some of the market’s most valuable collectibles, with key issues of Marvel Comics often demanding more than a quarter million dollars.

While no longer regularly writing comics, Lee is busier than ever. He moved to Los Angeles in 1981 and most recently launched POW! Entertainment to create, produce and license new characters. He hosted two seasons of the Sci Fi Channel show Who Wants to be a Superhero? And he’s executive producer of the several motion pictures based on his characters (Doctor Strange, Black Panther, Nick Fury, Thor, Ant-Man) that are yet to be released.

Surprisingly, Lee does not consider himself a collector. “Collecting is great,” he says with a laugh, “if you have the time for it!”

Q: Of the 15 top-grossing movies in the United States, George Lucas’ characters have grossed about $1.2 billion in ticket sales and your characters have grossed $1.1 billion.

A: Damn! He’s always beating me! I don’t like being in second place!

Q: Do you consider yourself one of the most successful creators in Hollywood?

A: Of course not! Lucas does movies. I only wrote a lot of comic book stories which other people have made into great movies. I had nothing to do with the movies and yet I seem to get so much credit for them. I feel like a phony!

Q: But Lucas created Luke Skywalker, you created Peter Parker. He created Darth Vader, you created Dr. Doom. Lucas wrote the stories, you wrote the stories.

A: Yeah, but he also produced and directed those movies. I didn’t have anything to do with the movies. That’s the only thing. I think I was very instrumental in making these characters famous and successful as comic book characters. In the comic book field, I did very well and I am happy to accept all the credit that might be heaped upon me. But the movies that have made all this money you’re talking about, while they were based on things that I wrote, they were written and directed and acted by other people. I had nothing to do with that. So I would be an idiot to compare myself to a George Lucas. I think I’m cuter! [laughs]

Enlarge

Q: People would still argue you’re on the same level. You created characters. You created stories. The movies are based on those characters and those stories. The similarities are there.

A: Look, I’m not going to fight it. I’m very flattered to be put in the same class. The only difference is, of course, I created probably more things.

Q: So there you are, working at Marvel Comics for more than 40 years, with comic books all over the place. But you never really collected them?

A: I never had time to be a collector. I was always too busy writing. You know, I’m probably one of the world’s greatest hack writers because I got paid for what I wrote. The more I wrote, the more money I made. So I was writing all the time so I could pay my bills. Collecting is great if you have the time for it! Also, when I was writing, I never for a minute thought that years later these comics would turn out to be collectibles. The most I was hoping was that the books would sell and therefore I would keep my job and maybe if I was lucky, get a raise at the end of the year. But I don’t think anybody in the business in those early days would have predicted or even thought what these things would turn into.

Q: Your wife Joanie is a collector.

A: She’s the biggest collector in the world! She’s always looking for anything that attracts her. Her tastes are very catholic. She likes everything. She was the first person I know who years ago latched on to African art when nobody knew what it was. She was buying these bits of sculpture from Nairobi and God knows where else. She collects paintings, sculpture, antique jewelry, watches. Anything that she finds attractive, she collects.

Q: Do you help her buy items or give advice?

A: Not at all! I know nothing about it. She’s the expert.

Enlarge

Q: Historians and critics say you created the modern superhero by creating extraordinary characters plagued by the same doubts and difficulties as ordinary people. Is that your legacy?

A: It has a lot to do with it. Before the Marvel characters, most of the superheroes had no private lives to speak of. The stories merely concerned their adventures in their superhero identity. I thought it would be interesting to show what their private lives would be like, too. What happens to a superhero when he’s not in costume? When he wants to go on a date? When he has an argument with his wife or girlfriend or can’t pay his bills? It seemed to me the more we knew about that person, the more we cared about him. So yes, that was a conscious effort on my part to make them more empathetic and believable and more interesting.

Q: The opposite of that were the heroes of the Golden Age, characters that seemed distant and not very human.

A: I felt that way about Superman. I never could get that interested in him. The only thing I knew about his private life was that he didn’t want Lois Lane to know that he was really Clark Kent. I don’t know where he lived. I don’t know how he paid his taxes, what kind of car he drove. He was just Superman. He was in the office, something would happen, he’d put on his costume and go off and fight the bad guy. And also, he was so invulnerable and so powerful that I never worried about him. Nothing could hurt him. In fact, obviously, the editors of DC felt the same way, which is why they eventually had to create Kryptonite just to make something interesting so you worried a little bit about him.

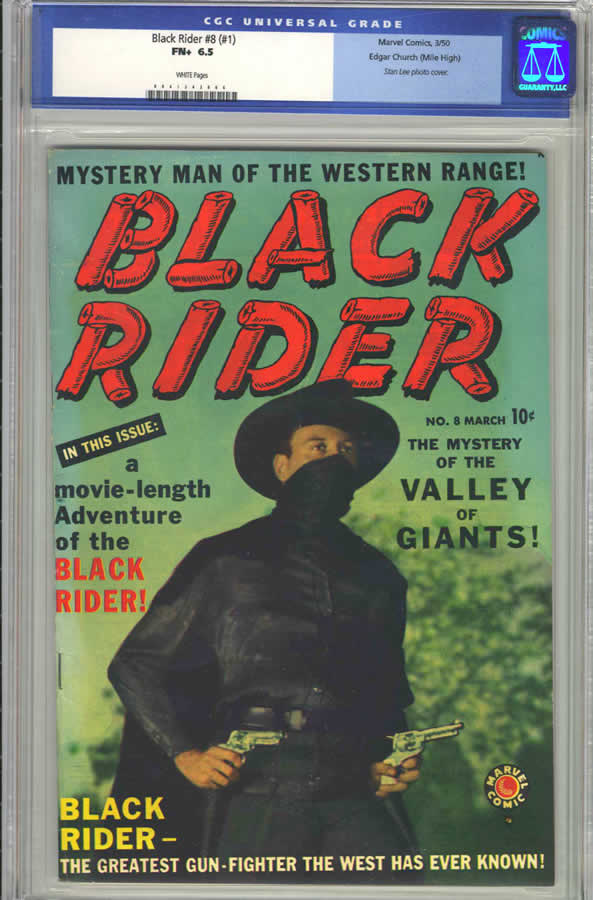

Q: The Black Rider was one of your personal favorite Western characters in the early 1950s. For the March 1950 issue, you used a real photograph on the cover of a model posing as the Black Rider. That was you?

A: I got a big kick out of that. I bought two pistols at the 5 and 10, put on a little mask, bandanna. Yeah, I love that cover. I was always a ham!

Q: I was looking at catalog descriptions of comic books and saw that you’re mentioned in Mad magazine #3, published by your rivals over at EC Comics in 1953. John Severin worked your name into a panel. Were you close to the Usual Gang of Idiots at that time?

A: I knew them. I was friendly with [founding editor] Harvey Kurtzman. A lot of them had worked for me. Dave Berg had worked for me. Al Jaffee worked for me. Jaffee did Ziggy Pig and Silly Seal and a lot of other strips. Jack Davis did some work with me. John Severin did work at Marvel. There are probably others. But I didn’t know about that mention!

Q: So it’s news to you? We’re breaking some news to Stan Lee?

A: That’s funny. I had absolutely no idea! But I’m not surprised! [laughs]

Q: You created Snafu in the middle 1950s. It was your company’s answer to Mad. You’re still proud of that first issue, which you wrote cover to cover.

A: I thought Snafu was great. The first issue, I wrote every word in that issue. That was a one-man show, that magazine. I think I may have written the second one too, but I don’t remember. I was very proud of it. I’m my biggest fan. I would read those pages and I would laugh! That’s always been my big rule in writing. If I don’t like something, I’m not going to expect someone else to.

Enlarge

Q: In the late 1950s, you were ready to leave comics. In your bio-autobiography, you say your wife Joanie got you excited again about comics by suggesting that you create heroes the way you wanted to, plots with more depth and substance, and characters who spoke like real people. Within months, you’d launched the Fantastic Four. How much does the Marvel Age owe to Joanie?

A: She really didn’t say “characters who speak like real people.” She wasn’t into comics at all. What she did say was you’ve been complaining that you don’t like the kind of stories that [publisher] Martin [Goodman] wants you to write, so why don’t you just write the kind of things you want to write? She said the worst that can happen is he’ll fire you and you want to quit anyway, so get it out of your system. Write what you want to write. I’d never thought of that. The woman is a genius! So that’s what I did, and that’s when I wrote the Fantastic Four and I tried to do it the way I would do it and luckily, it worked.

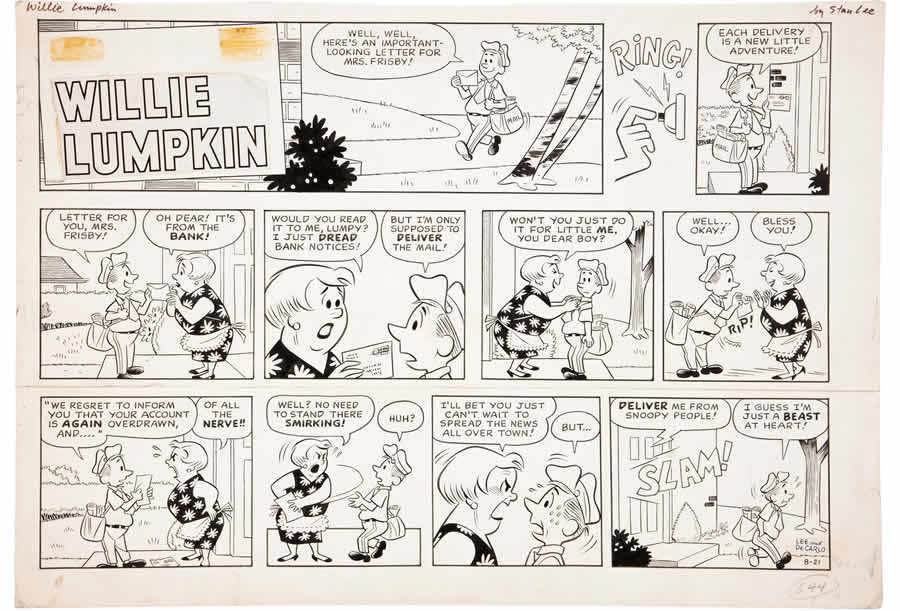

Q: Even though you had a full plate at Marvel, you wanted to do more. In the late 1950s, you started a newspaper comic, Mrs. Lyons’ Cubs with artist Joe Maneely. Then in 1960, you and artist Dan DeCarlo created the Willie Lumpkin comic strip, and that was followed by The Virtue of Vera Valiant, which you did with Frank Springer. In 1977, of course, you launched the Spider-Man newspaper strip. Why the desire to produce a syndicated strip?

A: I was always trying to do something that would break out and be a huge success.

Q: But Stan, wasn’t creating Spider-Man keeping you busy enough?

A: I didn’t know Spider-Man was that successful in the beginning. It took a few years before I realized we were on to something. I wanted to do something big, but we had bad luck. When we did Willie Lumpkin, I originally called it Barney’s Beat, and it was about a cop in the big city and the gags were great! They were big-city gags. So I sold it to Harold Anderson at Publishers Syndicate and he said, “Yeah I like this Stan, but nobody cares about big cities. Let him be a mailman in a small town. That’s what people like. They can relate to that.” Well, I wanted to sell the strip. So instead of Barney’s Beat, this big-city Irish cop, it became Willie Lumpkin, this nice mailman in a small town. I thought the strip was good. I came up with some great gags and DeCarlo did some great drawings, but nobody gave a hoot about a mailman in a small town. We couldn’t sell him to enough papers. And that’s one of the things – there are many things – but that’s one of the things that taught me never to do what someone else says you should write. Write what you want to write. It was a shame because it should have been a big hit and DeCarlo was such a great cartoonist to waste on a mailman in a small town.

Enlarge

Q: But you wanted to be syndicated because …

A: In those days, newspaper syndication was the big leagues and comic books were the minor leagues, the bush leagues. Maybe if you were good, you would graduate to newspaper syndication. The funny thing is today it’s almost reversed.

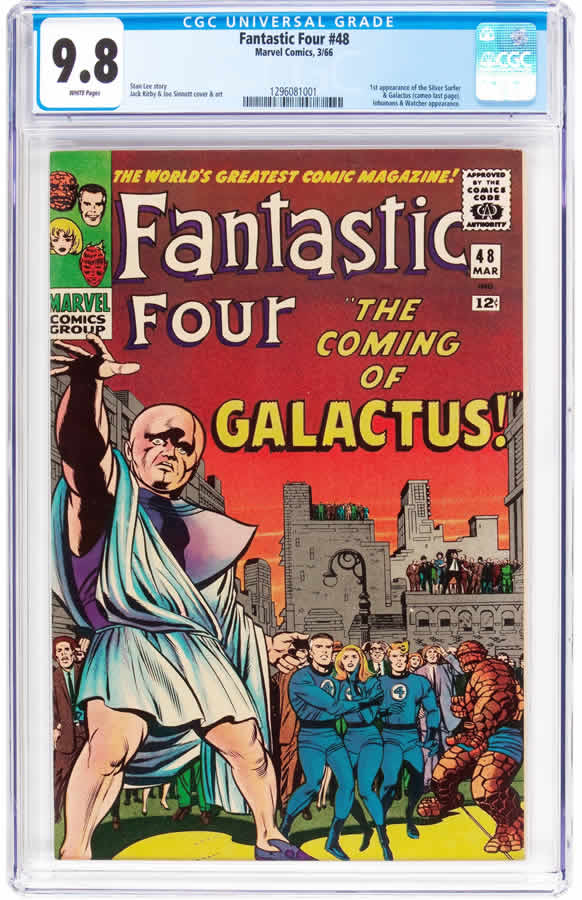

Q: It’s been written that “The Galactus Trilogy” in Fantastic Four #48 through #50, where the FF face down Galactus and the Silver Surfer, is the high point of Marvel’s publishing history. Do you agree with that?

A: I don’t agree or disagree. If people want to say that, great. The thing I get a kick out of, when I used to lecture in colleges, there was always a question and answer period. Inevitably, somebody would get up and say, “Regarding the Galactus Trilogy …” And I just loved it. It sounded like the Five Foot Shelf of Harvard Classics! “Regarding the Galactus Trilogy.” It sounded so classy! I loved that! I loved the sound of that!

Q: You’ve said that your best writing appeared in the Silver Surfer books, which first appeared in 1968. Why was he your favorite?

A: He was the most philosophical of the characters and I was able to put a lot of my own little bits of philosophy in his mouth. With him, I was able to get a lot of ideas across, ways that I felt about the world. I had him mouth my own voice.

Q: You didn’t do that with other characters?

A: Not really. I did it once with Thor. There was a scene in a Thor story where he meets a bunch of hippies who had – what’s the expression? – they had dropped out. He said, “If you’re unhappy with the way the world is, the thing to do is plunge in and make it better. Dropping out accomplishes nothing.” But Thor said it much better than I’m saying it now. I thought it was good. Really good. And I got a lot of mail, positive mail. I found whenever I would put in little bits of philosophy, the readers reacted very favorably, which I liked.

Q: A few years ago, you started releasing, through Heritage Auction Galleries, your file copies from your days at Marvel. Those included Spider-Man #1, X-Men #1, Amazing Fantasy #15 and Fantastic Four #1.

A: Those books that went to auction were just books that somehow I had accumulated. I didn’t save them as part of any savings plan or collection. There might have been a story that I liked that I didn’t feel like throwing the book away that quickly. I was always giving the books away! These were just some books that I hadn’t gotten around to giving away!

Q: What about original artwork?

A: You know, we never had room. We worked in one little office Marvel, which was Timely at the time. The original artwork was drawn huge, much bigger than it is now, on thick sheets of Bainbridge, or whatever they called it. The books of those days, they started out at 64 pages, then they were 48 and now they’re 32. But a 48-page book, with those thick boards, we had no place to put it. So we’d give the artwork away, the original artwork, to kids who’d come up to deliver a sandwich, or to a cleaning woman who didn’t want it. We didn’t know. We’d throw them away. Who knew?

Enlarge

Q: So how would you describe the auction experience with your file copies?

A: It was good and it was bad. Heritage handled it beautifully. It was a pleasure working with them. They’re a bunch of very competent and nice guys. They made it a very painless experience. But it was bad because I felt kind of nostalgic. I was sorry when I realized that these things do have value and people wanted them. I thought, “Why don’t I keep them?” But again, I didn’t have room for them. I would have had to live in a warehouse.

Q: In Fantastic Four #52, printed in 1966, you created the Black Panther, essentially the first modern black superhero. Were you that socially conscious or was this a matter of marketing, attracting an up-and-coming reader demographic?

A: I decided it was time we had a black superhero and I wanted to go against the formula. I figured I’d make him a great scientist who lived in an underground city. In fact, his whole life was like a superhero. His whole city had a secret identity. On the surface there were just thatch huts. But underground was the most modern scientific city that could be imagined. And he was a superhero. He was a popular character. … I tried to reach black readers, all minorities. We had an Indian named Wyatt Wingfoot who appeared quite a few times in Fantastic Four. I wanted to do some Latino characters, but I stopped writing before I got around to it.

Q: A few years ago, you co-founded POW! Entertainment and you’re chairman and chief creative officer. What are some of the projects you’re working on?

A: We have a first-look deal with Walt Disney Studios. We have three big movies in development at Disney. We have a number of television projects. We’re working on cartoons and a number of projects with Japanese companies. One of them is a manga strip. We’re doing some DVDs with original characters. We’re really keeping pretty busy.

Q: Your also working with Richard Branson’s Virgin Comics?

A: I’m going to try to do what I did with Marvel … create a whole universe of characters for them.

Q: When you started writing comics, you didn’t think too highly of comic writing and you thought someday you would do real writing – maybe a novel. But it seems your characters are just as popular and loved as any novel characters could possibly be.

A: Over the years, I’ve realized that the comic strip medium is a wonderful way to tell a story. It’s very interesting to read the dialogue and see the characters at the same time. Years ago, people said, “That makes people lazy. You should use your imagination. Just read a book. You don’t need to look at pictures.” But then I began to realize, nobody says that if you go to a movie. Nobody says that if you see a Shakespeare play on stage. Nobody says, “Well, you shouldn’t see it on the stage. You should just read the book.” I realized there’s no such thing as a bad way of enjoying a story. There are only bad interpretations and good interpretations. … A comic book can be beautifully done or it can be a waste of time. And so can a novel or a movie or a television show.

Q: Finally, I have to ask. Did you ever mail off $1 plus 25 cents for postage and handling to get your very own X-Ray Specs?

A: As a matter of fact, Johnson Smith was the company that sold a lot of that stuff. I still remember. I sent away for a lot of those things. The thing I sent away for most – I sent off for it a few times because I lost one – they have a little gadget that I felt was the most valuable thing in the world, because if you had this, you could do anything! I think it sold for 98 cents, maybe less. It had a little magnifying glass and a little compass and a little knife blade and God knows what else. To a kid, it was like, “Boy, this thing can do anything! I can look through the magnifying glass! I can see where I am! I can cut a piece of string!” I think it had a whistle on it, too. It was some sort of universal gadget. How I loved it!

Lee’s Creative Partners

Stan Lee’s collaborators in creating some of the most iconic characters in pop culture included Jack Kirby (Fantastic Four, X-Men, Iron Man, Mighty Thor, Incredible Hulk, Silver Surfer), Steve Ditko (Spider-Man, Doctor Strange), Bill Everett (Daredevil) and Don Heck (Iron Man). Here are Stan’s thoughts on each artist’s style:

- Jack Kirby (1917-1994): Created Captain America with Joe Simon. Called one of the most influential artists in comic history. “Almost everything that was different about comic books began in the ’40s on the drawing table of Jack Kirby,” states the book Kirby: King of Comics (Abrams, 2008). Stan says: “Jack was probably the most exciting and imaginative storyteller with his artwork that I’ve ever known. He could not draw a dull strip.”

- Steve Ditko (1927-2018): Among the cartooning cognoscenti, Ditko is one of the supreme visual stylists in the history of comics, states Strange and Stranger: The World of Steve Ditko (Fantagraphics Books, 2008). “Steve was a wonderful storyteller who told his stories with pictures,” Stan says. “His artwork was simpler than Jack’s, but he had his own distinct style. It was clear and crisp and told stories beautifully. He was always a pleasure to work with.”

- Bill Everett (1917-1973): “Brilliant. He both wrote and drew. Very talented. His artwork was very stylized. You could tell an Everett drawing a mile away. It was a shame he didn’t do more.”

- Don Heck (1929-1995): “His artwork was more sophisticated, less exaggerated, more realistic. He told a story beautifully.”

This story appears in the Fall 2008 edition of The Intelligent Collector magazine. Click here to subscribe to the print edition