ASSEMBLED BY A FATHER AND SON BEGINNING IN THE LATE 1950S, THE SOUTHSIDE BOBBY COLLECTION CONTAINS SOME OF THE BIGGEST NAMES IN SPORTS

By Joe Orlando

You know how the story goes: “I would have been a millionaire had Mom not thrown away my baseball card collection.” It’s a sentiment seemingly echoed by an entire generation of baby boomers. Long before the hobby became big business in the 1980s, the cards weren’t worth that much. It was often more of a nuisance to keep them as they were just taking up space. This led to the untimely death of many childhood collections.

One collector, however, a man known as “Southside Bobby” while growing up in the Chicago area during the 1950s and ’60s, had the exact opposite experience. Turns out Bobby’s mother acted like Mariano Rivera in his prime and saved the day, holding onto boxes of her son’s autographed sports cards, photos and postcards – a collection he and his father had spent more than a decade assembling. What makes this story even more remarkable is that Bobby didn’t collect in his adult years. In fact, his wife of approximately 50 years and his two children never had an idea that this trove existed until recently.

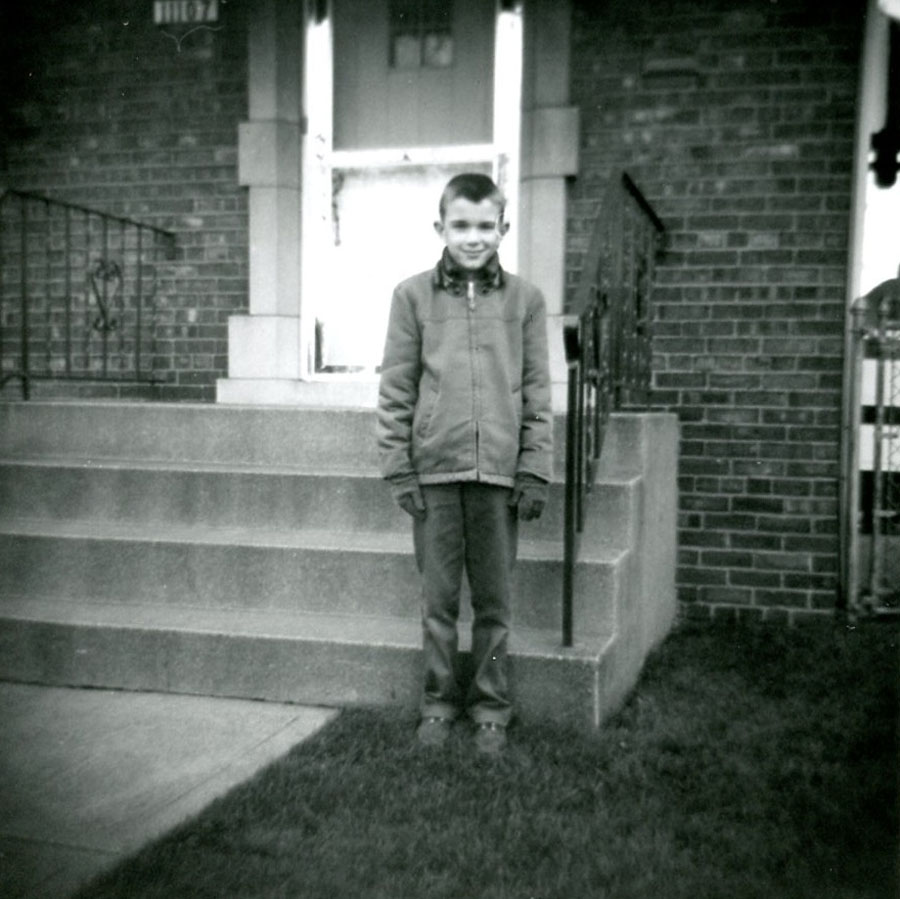

Pictured here in 1961, Southside Bobby chased autographs with his father in person, primarily from the late 1950s through the late 1960s. It was a labor of love.

Immediately following his father’s funeral in December 2000, Bobby’s mother presented him with his childhood collection, which had remained dormant since it was initially put together. As a result, Bobby canceled his flight home and drove with his in-laws and the collection packed in the trunk from Chicago to Georgia. “I knew how much the experience and collection meant to my father,” Bobby says now. “While I couldn’t imagine him throwing it away, I was relieved when my mother told me the good news.”

Amazingly, as tempting as it was to open the boxes and revisit the collecting experience, Bobby decided to leave them sealed until earlier this year. He had thought about opening the boxes over the years, but he kept this part of his personal history preserved. Then, as he started thinking more seriously about managing his possessions, he realized it was time to reveal the tangible result of his youthful endeavor.

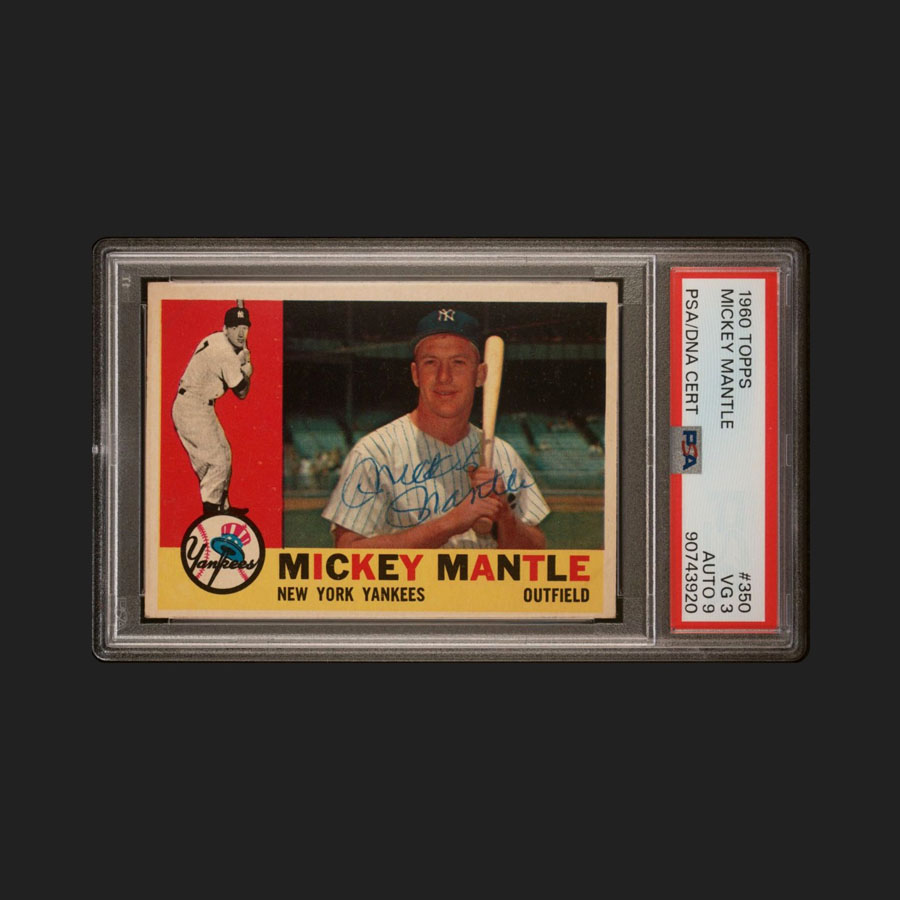

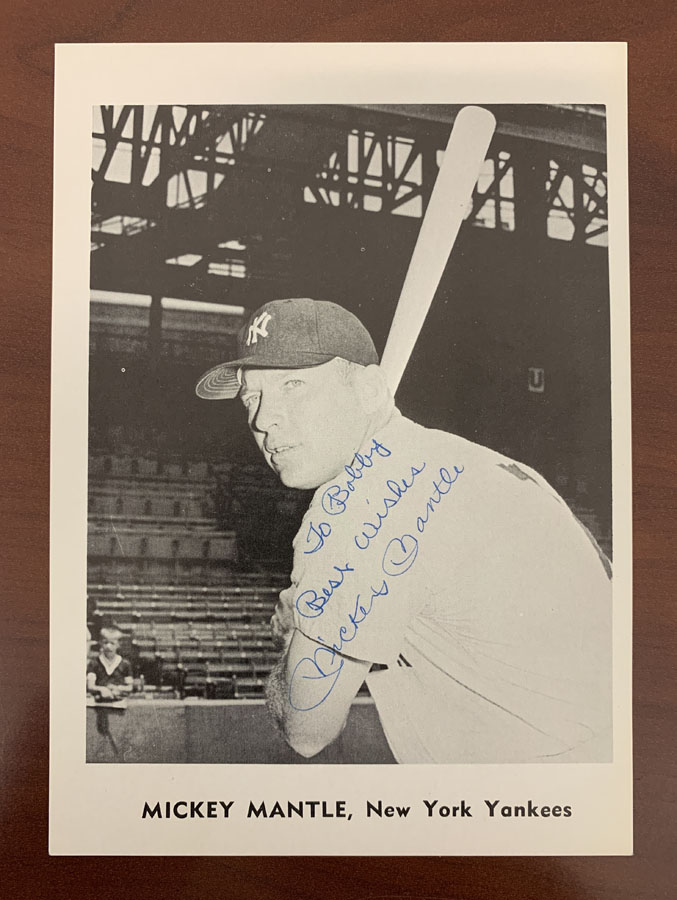

While signed sports cards have become increasingly hot in recent years, most examples were signed long after the cards were made. The Southside Bobby collection is made up entirely of period signatures, like this signed 1960 Topps Mickey Mantle.

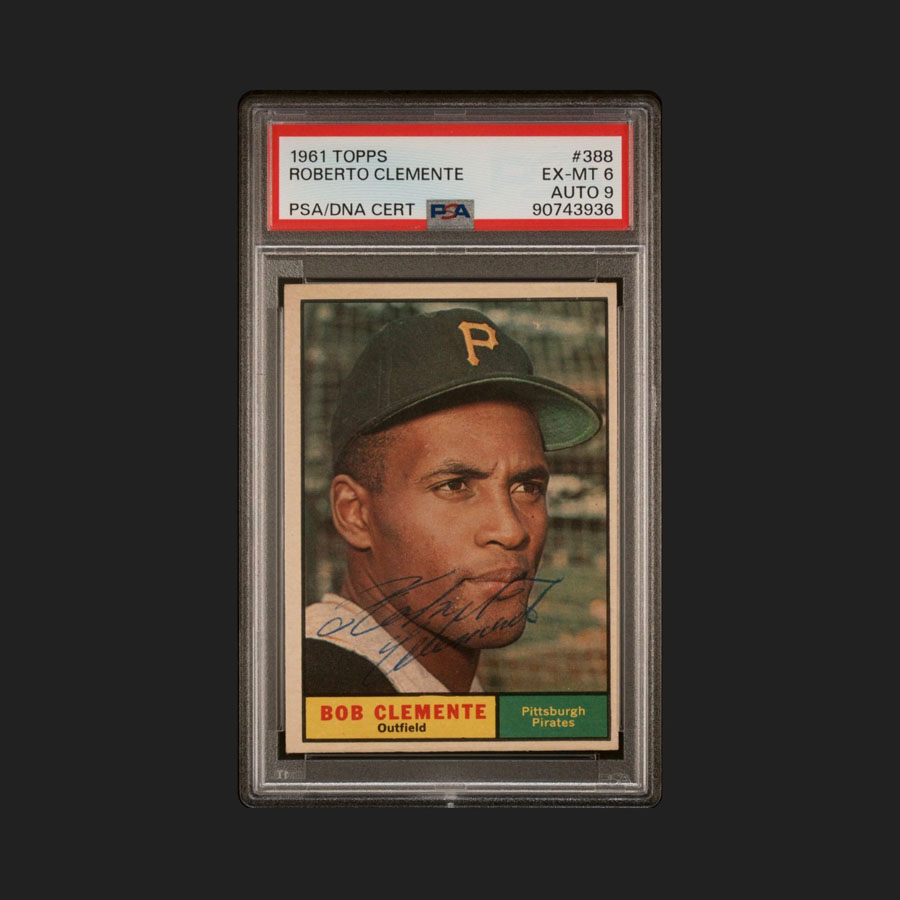

Roberto Clemente’s signature is one of the most stylish and prized in the hobby, and Southside Bobby’s collection has several beautiful examples on photos and baseball cards such as this 1961 Topps stunner.

Unlike many collectors who maintain the collecting drive found in their youth, Bobby did not. When he stopped chasing and mailing away for autographs with his father, the undertaking came to a grinding halt. For Bobby, it was more about the experience with his dad than anything else. “Opening the boxes after all those years really transported me back in time,” Bobby recalls. “I became consumed by it for a while as the memories started to flow.”

Now, via a series of sales conducted by Heritage Auctions, Bobby will part ways with an amassment that represented something much bigger than the autographs. It is part of his childhood in a bottle. No matter what the collection sells for, the nostalgia and memories are priceless.

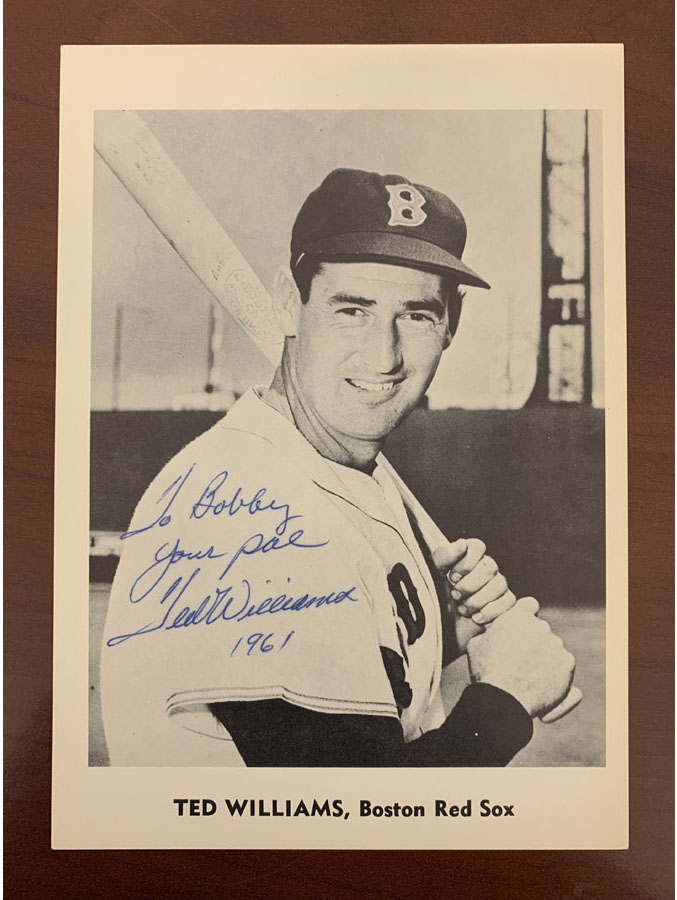

Trading cards make up most of Bobby’s collection, but he also acquired autographs on player photographs, like these two images of Ted Williams and Mickey Mantle, both of whom wrote personalized messages to Bobby.

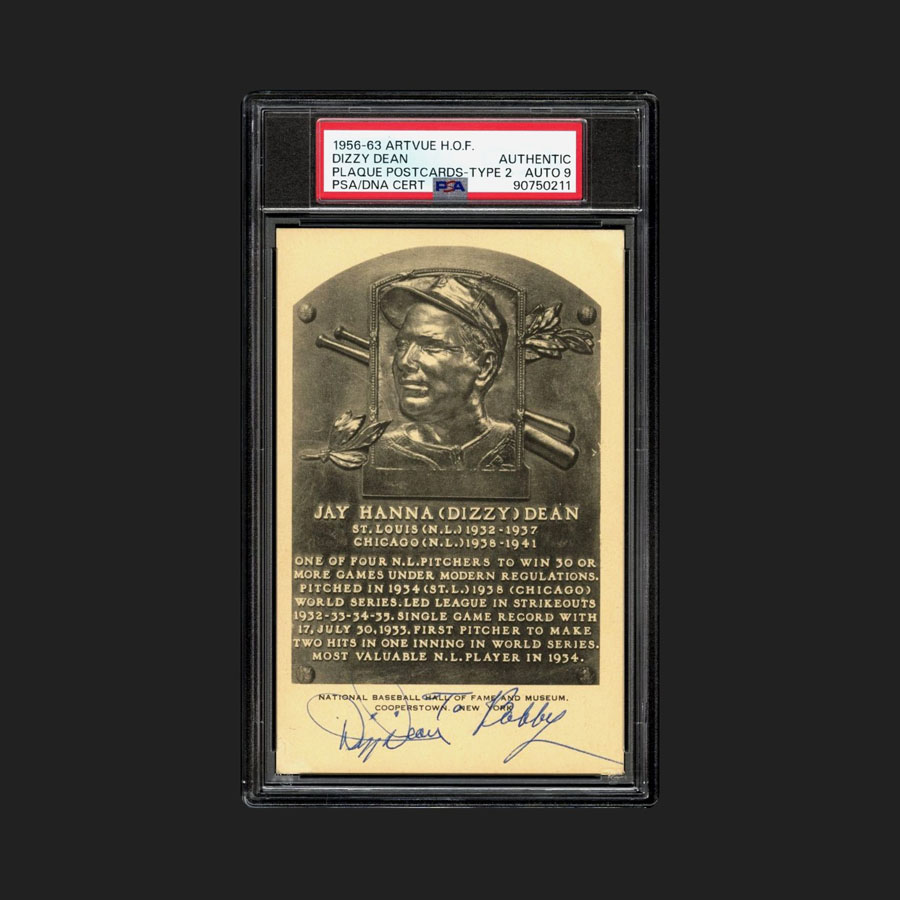

The trove consists of more than 3,000 signed items, which Bobby acquired primarily in person. He chased autographs with his father, mostly in the Chicago area, from the late 1950s through the late 1960s. Although he added a few autographs to the collection in the early 1970s, the main event was over. Most of the autographs were obtained on trading cards, but there are photos and Hall of Fame Plaque postcards, too. Some of the biggest names of the day from the baseball and football worlds can be found within the hoard.

Those names include the likes of Hank Aaron, Jim Brown, Roberto Clemente, Sandy Koufax, Mickey Mantle, Willie Mays, Johnny Unitas and Ted Williams. The haul of signed cards also includes some scarce common names that can only be appreciated by the savviest collectors – Walt Bond, Don Hoak, Fred Hutchinson, Sam Jones and Duke Maas, just to name a few.

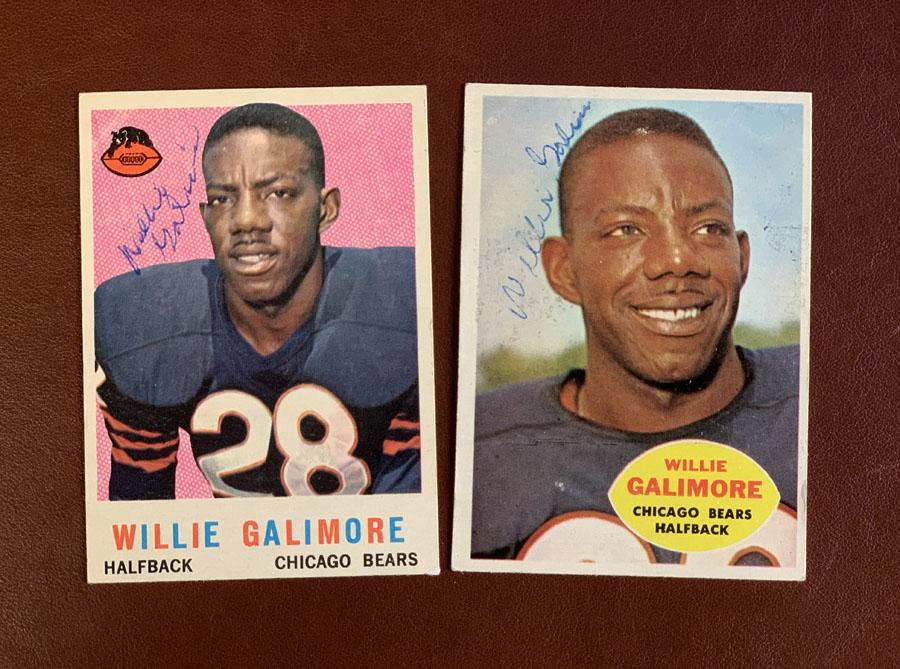

One of the more intriguing signed cards is of former Chicago Bears halfback Willie Galimore. Galimore was an outstanding collegiate and professional football player who tragically died in a car accident in 1964. He was known for his explosive speed and agility, which helped him earn enshrinement in the College Football Hall of Fame in 1999. His pro career and life were cut far too short.

The Southside Bobby collection not only contains countless stars, but it also features plenty of elusive rarities, like these two signed cards of former Chicago Bear Willie Galimore. Tragically, Galimore perished in a car accident in 1964 at the age of 29.

Within the collection, many stories like this are waiting to be told. The reason for the rarity varies from athlete to athlete, but it leaves collectors with limited options as a result. For those trying to build or complete wholly signed sets, there are substantial groups of 1959, 1960 and 1961 Topps baseball cards, as well as dozens of other signed baseball and football cards from the years Bobby was actively pursuing them.

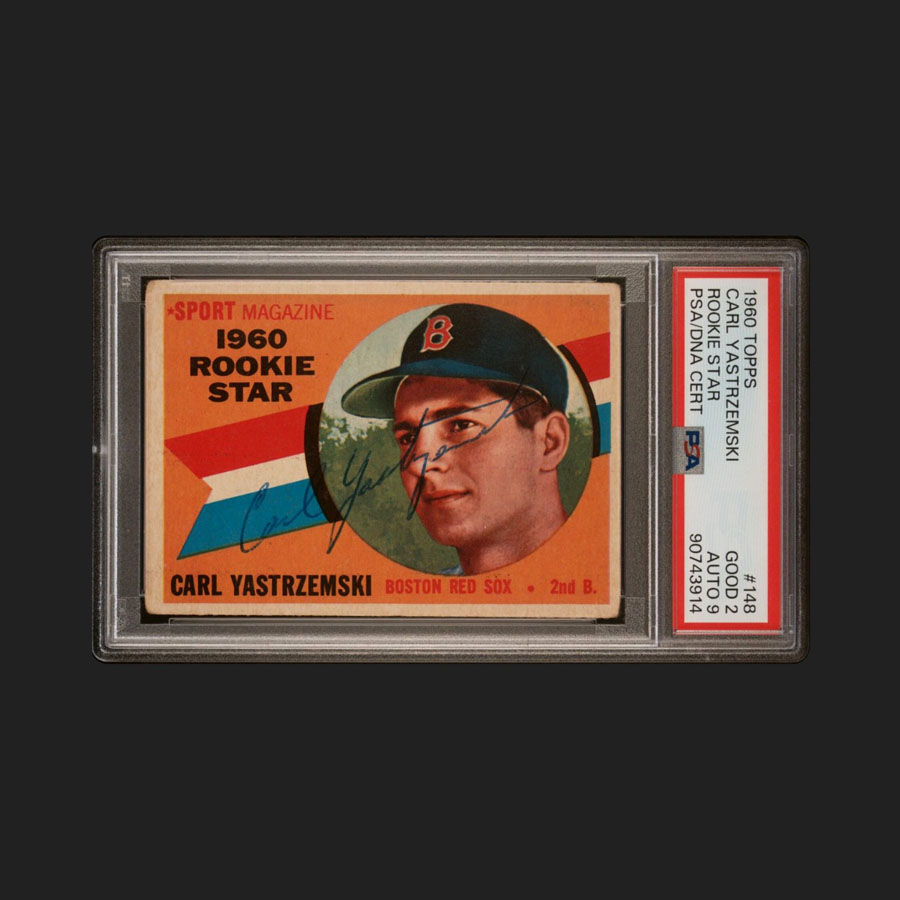

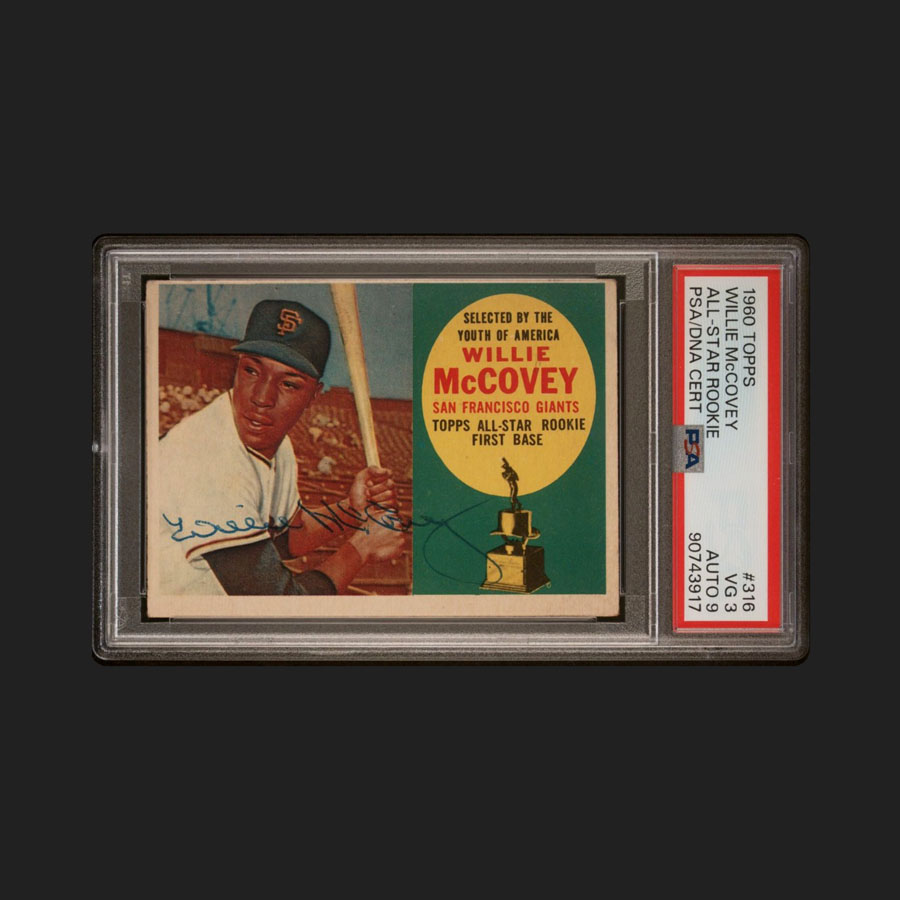

Perhaps the best part of all, even beyond the provenance, is the fact that the signatures are all “period” examples, often in blue ballpoint pen. They capture a moment in time. These weren’t cards signed many years later in black Sharpie at a show; most were captured in their natural habitat at a time when the ballplayers were active, and with a more precise writing instrument so you can make out more of the detail. The premium associated with period signatures can be hard to quantify, but there is no doubt that astute collectors prefer them.

When asked, Bobby can recall how he was able to acquire these autographs like it was yesterday. At Wrigley Field, his favorite place to secure Chicago Cubs autographs was on Clark Street near the left field entrance, across from the local fire station. For visiting National League players, his preferred spot was on Clark and Sheffield Avenue near the home plate entrance. The key was to try after the game since the autograph seekers were more dispersed and less concentrated in certain areas. At Comiskey Park, where the Chicago White Sox played in the American League, the streets were different, of course, but the process was similar.

When baseball teams from either league would come into town, the host hotels were also terrific locations to hunt for autographs. Hotel Del Prado and the Conrad Hotel by Hilton were hot spots. Bobby, dressed in a suit and tie to better fit in at the fine establishments, would begin scouting the landscape early after the visiting squads settled in, around 8 a.m. each day. The hope was to catch some of the players heading to or from breakfast onsite. Around 10:30 to 11 a.m., the players would start boarding the team bus as it was time to head to the ballpark.

It’s one thing to find signed rookie cards, but when the card and the autograph date to the same era, like they do on these Hall of Famer debuts, the collector gets the best of both worlds.

One baseball star, who ultimately became a Hall of Famer, presented one of Bobby’s biggest challenges. Luis Aparicio, who transferred from Venezuela and spoke very little English at the time, lived at Hotel Del Prado, where many visiting players were stationed. Bobby had zero success at Comiskey Park, where Aparicio and the White Sox played, so he tried finding him at the hotel.

One day, Bobby located the exact room where the standout shortstop was living. While admittedly nervous, he decided to give it a shot. Bobby vividly remembers Aparicio’s wife answering the door while their two children played in the background. She was gracious and took the cards to her husband to sign, and he obliged.

“The environment surrounding the players at that time would be hard to imagine for a young person today,” Bobby says with a chuckle. “Most of the sports figures were playing for the love of the game in those days. The respect and appreciation they showed the fans was heartwarming.”

Case in point: When Bobby wanted to obtain the autograph of Johnny Mostil, who was included in the 1961 Fleer Baseball Greats set, he simply went to his house. Mostil, who once played for the White Sox in the late 1920s, was living in the same general area where Bobby grew up in Whiting, Indiana. Bobby and his dad drove to Mostil’s house, and the former Chicago ballplayer was accommodating. “I realize now how fortunate I was to grow up during that time,” Bobby says. “The window for opportunities like this has virtually closed.”

When it came to football, training facilities and host hotels almost always produced better outcomes for Bobby than on game day. The Chicago Bears training camp was based in Rensselaer, Indiana, at St. Joseph’s College, and access to the players was practically unrestricted. Unlike today, there was no ticket lottery or any tickets required to get in. There was also no security to speak of. “I could walk right to the practice field unobstructed,” Bobby remembers. “It’s the way things were then – the barriers between professional athletes and civilians were much lower, and the commonality was much greater.”

The immense collection is anchored by hoards of signed trading cards captured while the players were active, but it also includes some tough Hall of Fame Plaque postcards that needed to be acquired by mail, like this one personalized to Bobby by Dizzy Dean.

The thrill of obtaining autographs in person was hard to match, but sometimes Bobby had to employ other means to get the signatures he was seeking. Bobby started building a small collection of Hall of Fame Plaque postcards. These were not the more common yellow versions that most collectors see in the marketplace today. These were the black-and-white Albertype and Artvue (Types 1 and 2) postcards, which were issued in the 1940s, 1950s and 1960s, and are much more elusive today.

Active players were one thing, but retired ones required a different kind of effort.

While hard to believe in this day and age, Bobby would call or write the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum in Cooperstown, New York, and the office would share the personal mailing addresses of the players. He would send the autograph requests along with self-addressed, stamped return envelopes. Bobby received responses from Mickey Cochrane, Dizzy Dean, Joe DiMaggio, Jimmie Foxx, Hank Greenberg, Rogers Hornsby, George Sisler, Pie Traynor, Paul Waner and more.

Beginning in August, Heritage will present the Southside Bobby collection in stages. As hard as it is for Bobby to let go of something so sentimental, a dilemma many other collectors face, it’s time for the next generation of custodians to have their turn.

JOE ORLANDO is Executive Vice President of Sports at Heritage Auctions. He can be reached at JoeO@HA.com or 214.409.1799.

JOE ORLANDO is Executive Vice President of Sports at Heritage Auctions. He can be reached at JoeO@HA.com or 214.409.1799.