WITH MOVIES LIKE ‘THE FOX AND THE HOUND,’ ‘THE ARISTOCATS’ AND ‘ROBIN HOOD,’ THE ANIMATION GIANT’S SO-CALLED DARK PHASE BOASTED PLENTY OF BRIGHT SPOTS

By Christina Rees

If you told American kids in the mid-1970s that they were living through “The Dark Age” of Disney animation, they couldn’t have believed it. Disney feature animation may not have been central to our lives in those years (instead of home video and streaming, we had only the occasional Sunday evening TV appointment with The Wonderful World of Disney), but theatrical releases at the time included the endlessly charming The Aristocats (1970), the cheeky and dramatic Robin Hood (1973), The Many Adventures of Winnie the Pooh (1977) and The Fox and the Hound (1981). We loved these fresh movies and trekked with our parents to local cinemas to soak them up.

And, really, how could you damn lovable characters like Thomas O’Malley or Little John or Tigger or Tod and Copper to anything called The Dark Age? Surely these classic Disney icons deserve better.

Here’s the rub: Disney’s animation history is unofficially (though quite authoritatively) split into eras, starting with its Golden Age, which kicked off in 1937 with Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. That era lasted until Walt Disney’s death in 1966 and the release of The Jungle Book in 1967 (though some subdivide this long stretch to include “The Wartime Era” and “The Silver Era”). Disney has, of course, more recently enjoyed its mega-hit-packed Renaissance, heralded by The Little Mermaid in 1989 and ruling the box office for years with The Lion King, Beauty and the Beast and many more. Disney animation’s current cycle is tentatively labeled the Revival Era (think Frozen and Moana). While The Walt Disney Company doesn’t officially claim its era names, it occasionally and informally refers to its Golden and Renaissance eras given their popularity.

The animation and live-action kid-centric features the studio released between 1970 and 1988 are tossed into the somewhat taboo revisionist-history era termed The Dark Age or Dark Ages (aka The Dark Phase or The Bronze Era) – a moody and complex term that encompasses more than one meaning, as well as a catalog of movies that left an indelible mark on a grateful generation. Animation collectors are crazy for these features, too, as proven by auction records. The animation Dark Age was bookended by The Aristocats in 1970 and Oliver & Company in 1988. Other Dark Age crowd-pleasers include The Rescuers, The Black Cauldron, The Great Mouse Detective and that marvelous outlier hybrid Who Framed Roger Rabbit – although many animation experts place Roger Rabbit in the Renaissance era.

Depending on whom you ask or which cinema repository you turn to, one definition of the “Dark” in Dark Age most directly references a studio full of animators making their way after the death of their visionary leader Walt Disney. By the time of The Jungle Book’s release in ’67, Disney’s masters of animation had come up through the system and certainly understood the Disney remit, but culturally and politically, the world was a transformed place, and audience taste was rapidly changing. The once-pioneering aesthetics and disposition of Disney Golden Age animation – romantic, fluid, optimistic and reflecting a more conservative chunk of the century – started to feel out of touch during a tumultuous 1960s and unflinching 1970s, which (as the old studio system lost its iron grip) demanded from Hollywood a grittier independent cinema. In that sense, the “Dark” Disney also related to the times. The music and voice acting in the Dark Age movies, like the animation itself, feel thoroughly modern. The banter veers into flip and slangy, the songs sound like Bob Dylan teamed up with Neil Diamond, and the animation looks more jagged and bristly – it’s moved along from the watercolor dreaminess of Pinocchio and jogged past the midcentury bold graphic punch of One Hundred and One Dalmatians.

Young moviegoers watching, say, Robin Hood witnessed scenes of tiny talking mice exhausted, starving, demoralized and shackled by the neck in Prince John’s dungeon. This isn’t to say that the earlier Bambi and Dumbo don’t have their moments of despair, but those scenes were treated as key plot points, whereas the suffering of Disney characters during its Dark Age shared some DNA with the casual relationship to violence of era-defining movies like One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest or The Deer Hunter. That may sound hyperbolic, but even the most mainstream entertainment had slipped down a moralistically pulpy, slippery slope. The Rescuers’ plotline and harrowing scenes – featuring child endangerment and kidnapping, criminal corruption, threats of murder at gunpoint – in a sense may as well have been penned by Paul Schrader.

“Dark Age” also refers somewhat obliquely to the fact that a lot of Disney feature outings of the time didn’t enjoy the box-office fireworks their earlier animated showstoppers had. The Dark Age movies were popular but not era-defining. The Fox and the Hound isn’t a bad-looking movie (I’m a huge fan), but it doesn’t seem to be self-consciously interested in reinventing any aesthetic wheel, either. During this so-called Dark Age, Disney was leaning back into an animation process that worked for audiences as the studio experimented with live-action features and more mature-teen content like Escape to Witch Mountain, Freaky Friday, the Herbie the Love Bug series, the radical sci-fi Tron and even the co-produced Robert Altman-directed oddity Popeye. If the studio was struggling to define itself, it certainly didn’t suffer any loss in momentum; all told, between animation and live-action (and several hybrid outings), Disney released some 70 features between 1970 and 1989. In that regard, even before its explosive Renaissance, Disney the institution was becoming ever more present and workaday in the lives of kids and grown-ups alike.

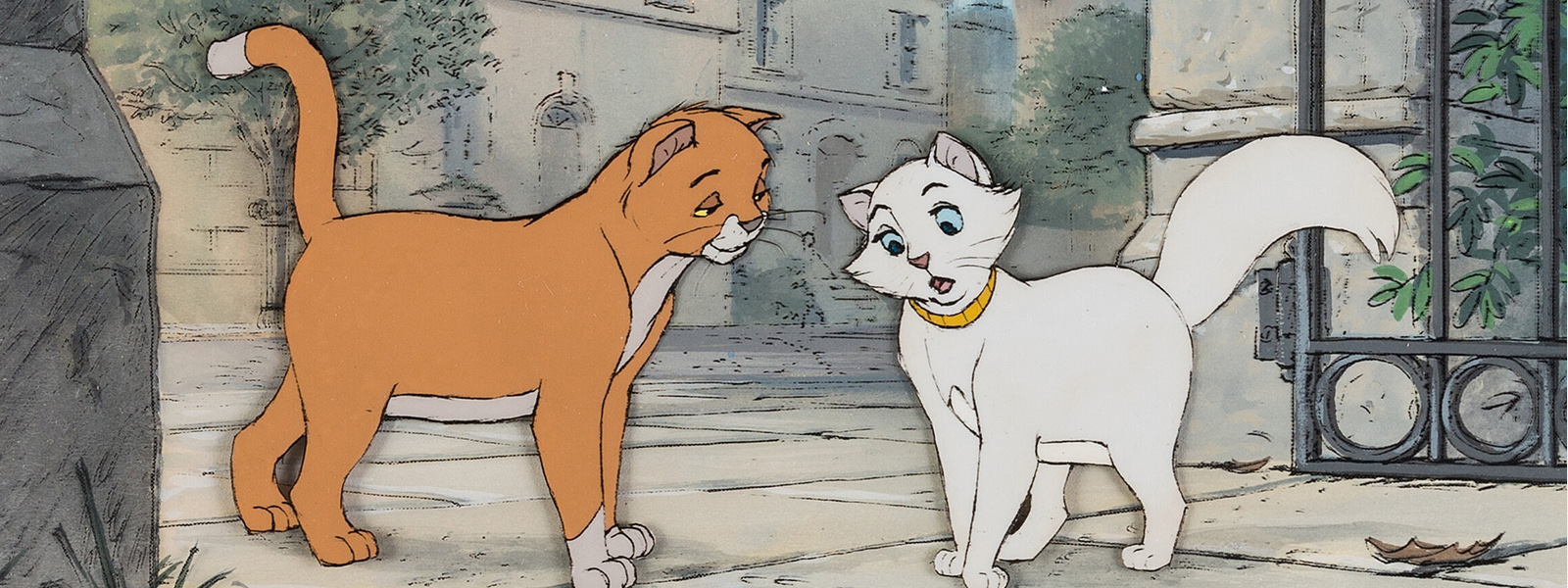

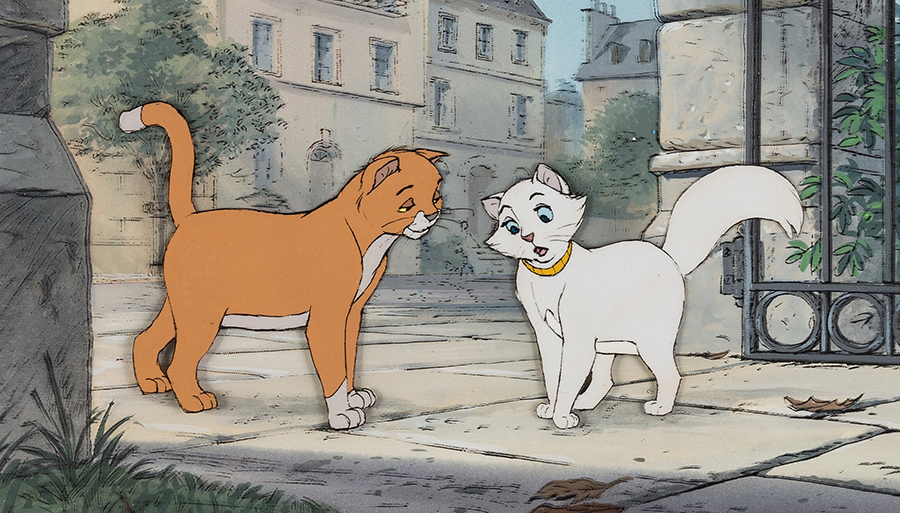

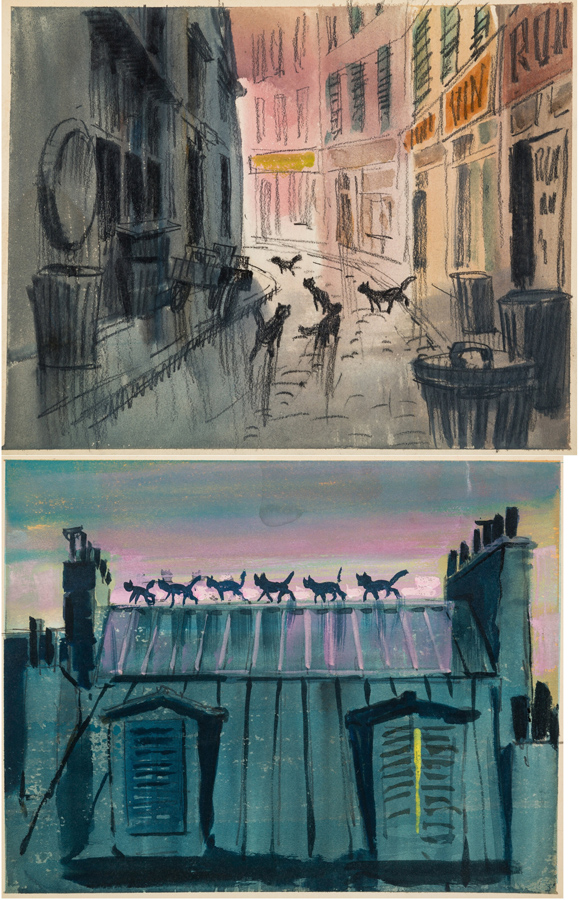

For this Gen-Xer, the three standouts of the period that defined my relationship with Disney animation are The Aristocats, Robin Hood and The Fox and the Hound. I’m not alone in this fondness: At Heritage Auctions – which dominates the Disney animation market – cels and original concept artworks from these and other Dark Age features perform remarkably well. In recent years, a Fox and the Hound original concept painting, lyrical and lovely, by Mel Shaw featuring Tod, Big Mama and the crows sold for $9,600, and a stunning and encompassing pan production cel setup featuring Tod and Copper sold for $7,200. A Robin Hood Maid Marian and Robin Hood production cel showcasing the couple as newlyweds brought $7,800, and a production cel of a solo Robin Hood (arguably the most charismatic leading male of any Disney movie and the first “crush” of countless Gen-Xers) sold for $5,160. An Aristocats production cel with a key master background featuring Thomas and Duchess sold for $3,840, and a pair of Aristocats concept paintings by Disney background painter extraordinaire Ralph Hulett sold for $4,560.

In other words, the collective affection for Disney’s remarkable era of understandable growing pains is warm, wistful and anything but dark.

CHRISTINA REES is a staff writer at Intelligent Collector.

CHRISTINA REES is a staff writer at Intelligent Collector.