‘HOW THE HELL DID WE PULL THAT OFF?’: TWO OF THE VISUAL EFFECTS MASTERS BEHIND THE 1982 CLASSIC EXPLAIN HOW THEY MADE THE GROUNDBREAKING FILM

By Robert Wilonsky

The moment Tron begins, it’s literally off to the races. Just one minute into the 1982 film that transformed cinema, the audience is dropped into a sequence unlike any other in moving-picture history: A videogame player in “the real world” drops a quarter into a machine, grabs a joystick, then begins steering one beam of light against another illuminated on the screen. The camera pushes in, and suddenly we’re inside the game as two Light Cycles roar along a stark, colorful digital grid, each trying not to crash into the other or the light trails left in their wake. It’s climax as introduction and a warning, too: Strap in and hang on.

Tron, written and directed by Steven Lisberger with the assistance of hundreds of fellow revolutionaries, didn’t hide his intention to dazzle and delight. Watching the movie about “programs” using digital frisbees and motorbikes to overthrow the ravenous Master Control Program is like pulling up a chair at a dinner table piled to the ceiling only with desserts. Nor did the filmmaker feel the need to explain what was happening as we bounce between our world and a digital realm in which “users” (or humans) – including a proto-Dude Jeff Bridges, man – are represented by their irradiated avatars.

THE ART OF ANIME AND EVERYTHING COOL VOLUME IV SIGNATURE® AUCTION 7311

October 20-23, 2023

Online: HA.com/7311

INQUIRIES

Jim Lentz

214.409.1991

JimL@HA.com

The movie, made for Disney when no other studio could understand its possibilities, was cinema’s black-and-white silent-film past and its blindingly bright computer-rendered future rolled into a neon thrill ride that was so revolutionary it’s still considered avant-garde. Before cyberspace, before The Metaverse, before privacy became a thing of the past and our existences were lived and lost online, there was Tron.

“Tron keeps fading away,” says Harrison Ellenshaw, Tron’s visual effects supervisor and associate producer. “But I always have to look at it now and then. And when I do, I always go, ‘Wow, how the hell did we pull that off?’ We kind of reinvented the wheel. You couldn’t do it today. It was a slice of time. There was never a film made like it before, and there will never be a film made like it again.”

And there will never be an auction like this one again: In late October, Heritage Auctions will offer nearly 80 lots of original production-used artwork and artifacts from Tron from the collections of two of its key makers, Ellenshaw and technical effects supervisor John Scheele. For the first time, collectors and the film’s fans will have a chance to own a tangible piece of The Film That Changed Everything. It’s like being able to grab hold of a dream.

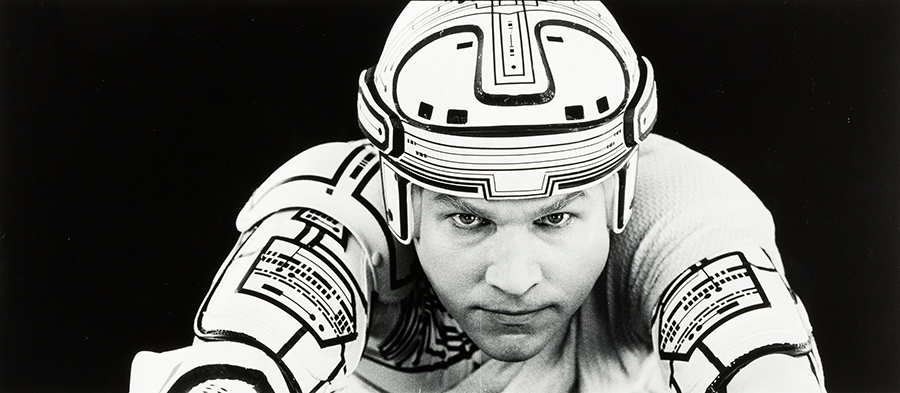

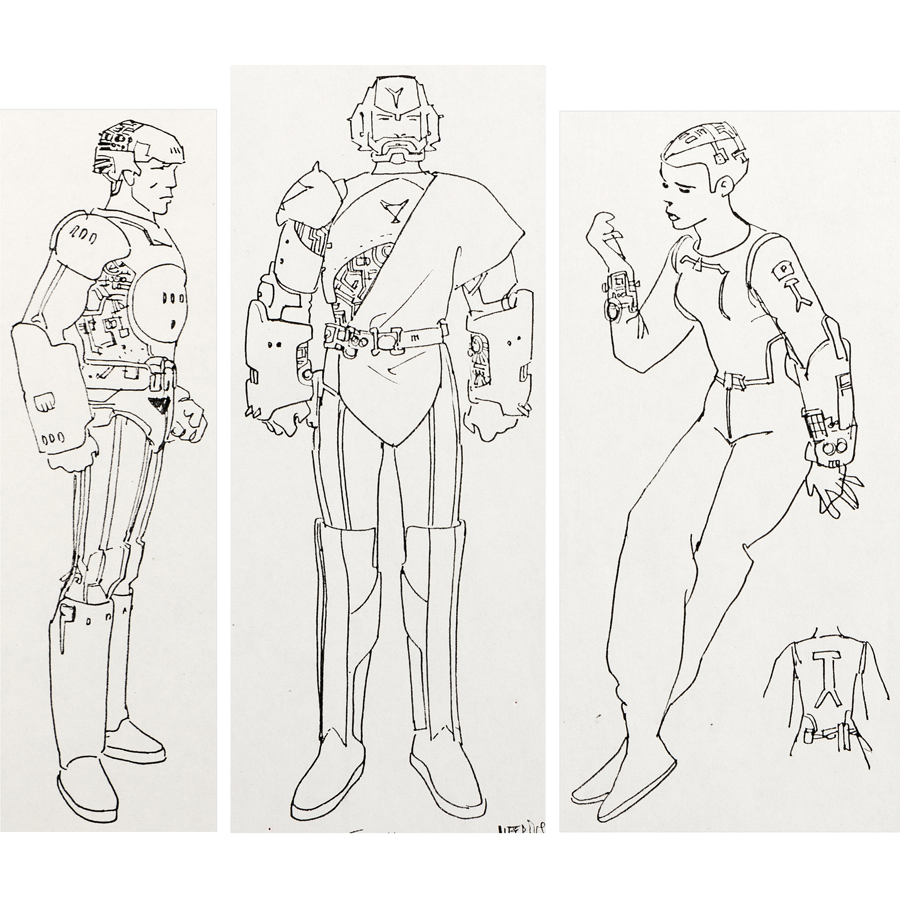

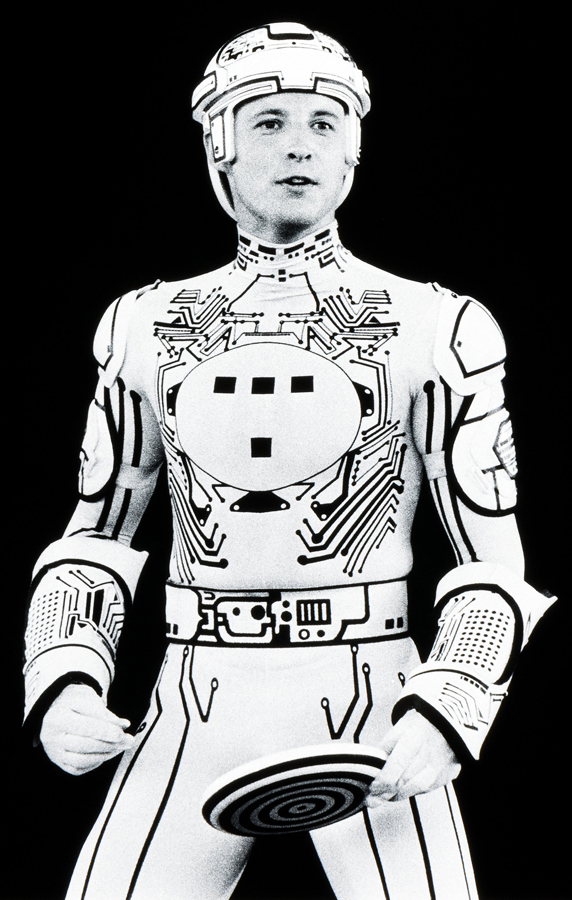

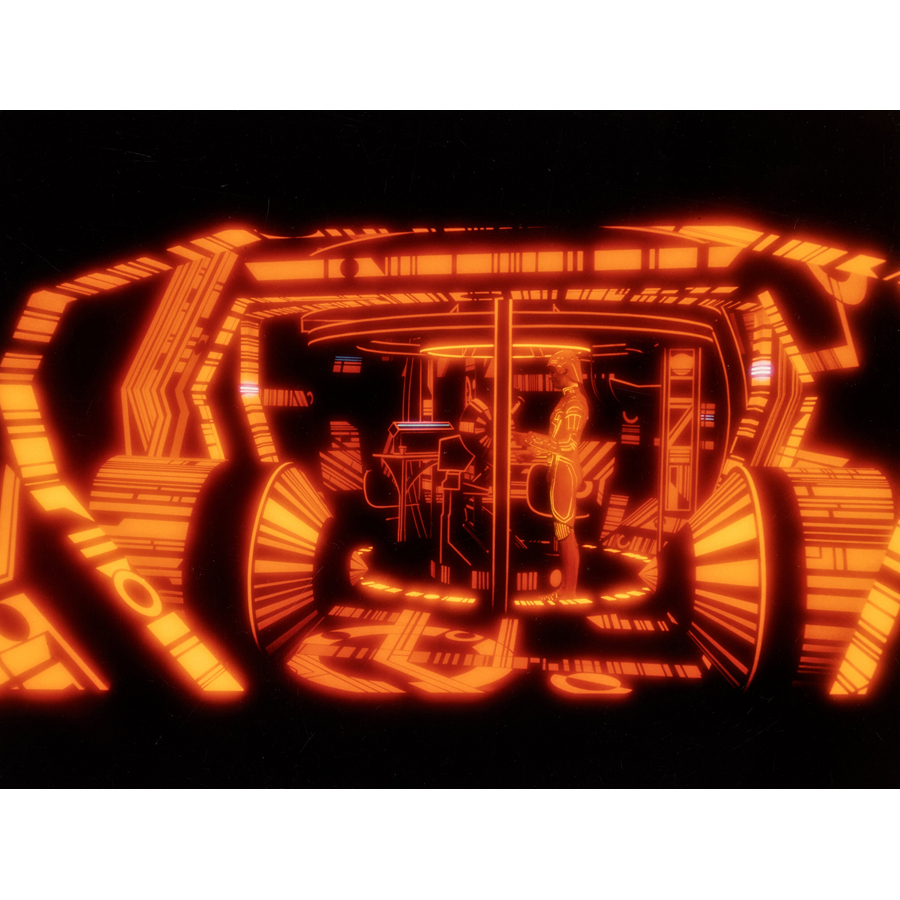

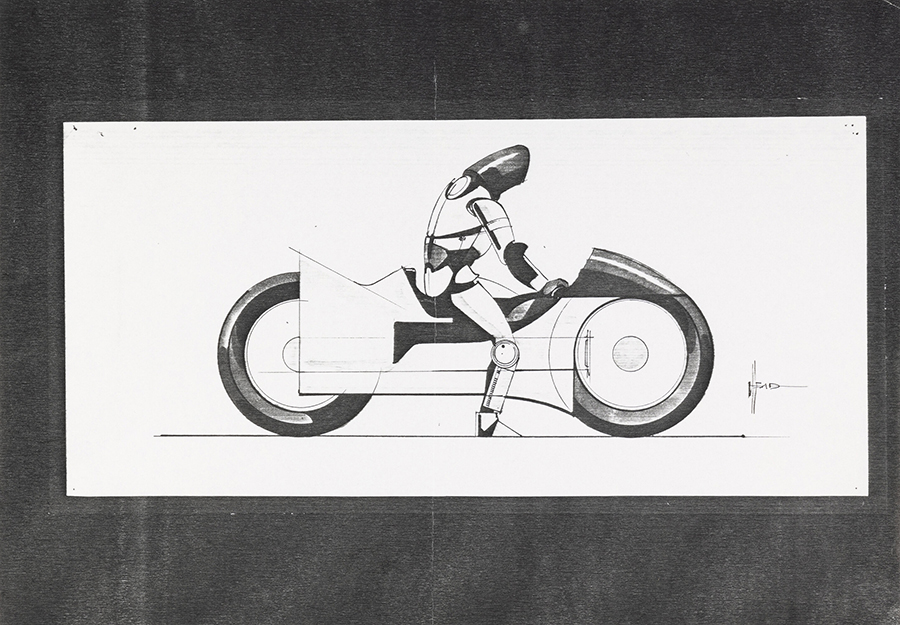

Among the offerings in Heritage’s October 20-23 The Art of Anime and Everything Cool Volume IV Signature® Auction, you will find numerous concept sketches by Syd Mead and Moebius, the visionary artists who designed the characters and their costumes, the Solar Sailer and the Light Cycles that inspired the new TRON Lightcycle Run at Walt Disney World. Here, too, are dozens of the high-contrast black-and-white Kodalith transparencies, which were individual frames blown up to twice their size so animators could illuminate the actors, sequences and world inside our own.

Roger Ebert was among Tron’s earliest and loudest champions, hailing the film as “a technological sound-and-light show that is sensational and brainy, stylish, and fun.” But he was only a little right when noting that the filmmakers were “using computers as their tools” and that despite its actors, Tron “is an almost wholly technological movie.”

Quite the opposite: The film was shot on 70mm on a set with an entirely black backdrop, and its actors (Bridges, Bruce Boxleitner, Cindy Morgan, David Warner, Barnard Hughes) dressed in white costumes. Then the footage was “dismantled,” as Lisberger once said, so that every frame could be animated by hand – just like every Walt Disney classic before it. Even more artists would fill in the blanks, shining light through the mattes to make them glow. Airbrush artists made that light appear to blur, rendering the unreal somehow more real.

The process was painstakingly laborious: It took months to finish scenes that could be completed today in a single afternoon. As Looper explained in its “Untold Truth of Tron,” the light cycles “were actually animated … using 75,000 frames of ‘special animation cels’ called Kodaliths. These Kodalith animations contained every single piece of information about how characters, sets, and motion would eventually look, and were a huge feat to maintain organized.”

Scheele says that “all the touch-up work you’d do today with Photoshop was done with airbrushes on an enlarged cel. The brilliance of the Disney method was they enlarged everything to such a large cel size you could work on it by hand. To have people really work on something – and a group who are obsessive weird people – you have to bring it up to a size you can work on. Watching those pictures go from black-and-white to color was an amazing experience: There was brilliant, pure color that glowed, that had depth. It was a truly illustrated world.”

As Scheele likes to say, they didn’t call it “computer-generated” back then. It was, instead, computer-simulated. Maybe that’s why, all these years later, it can be challenging to get your head and arms around Tron, which – in the shorthand – was made using seemingly every animation technique that had come before and every computer trick that came after. There has been no shortage of attempts to unravel its mysteries, including two books about its making and a documentary accompanying the 20th anniversary DVD release.

The offerings in this auction go a long way toward revealing the artistry involved in its making: You can see, for instance, how Lisberger’s rough sketches gave way to Moebius’ character designs, which looked like his comic-book characters come to life. In Syd Mead’s Light Cycle sketches, you can see that “transportation design [w]as his first love,” as his website notes.

For this auction, Ellenshaw also provides his integral hand-drawn boards showing why it was essential to shoot the film against a black background rather than the white background initially proposed. Here, too, are the earliest attempts at rendering humans inside a computer, and Walter Cronkite himself – TRONKITE, as it were – “inside” the game with Ellenshaw for CBS News.

And in those Kodaliths, those frames shorn of their animation and airbrushing and backlight-painting, you can appreciate the sheer beauty of the filmmaking.

For a film set in a computer and hailed as a technological marvel, Tron feels decidedly human, warm to the touch – more so, in fact, than most of the special-effects spectacles that would follow.

Don’t Miss an Issue

Sign up now for Heritage’s biweekly Intelligent Collector e-newsletter, filled with auction highlights, expert advice and interviews with top collectors.

“I feel the same way,” Ellenshaw says. “This is not antiseptic. This is not sterile. One of the great shocks of Tron was that it didn’t get an Oscar nomination for its visual effects. Richard Edlund [one of the founders of Industrial Light & Magic] told me the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences all thought robots and computers did it. Really? The members of the Academy thought that? But there was still the old guard that thought it needed to be matte paintings and sets and mechanical effects and you have to blow up stuff. It was such a new thing that nobody really understood it. Nobody understands it today. Which is what makes it so much fun.”

ROBERT WILONSKY is a staff writer at Intelligent Collector.

ROBERT WILONSKY is a staff writer at Intelligent Collector.