THE WORLD WAR II HEROINE’S CAPTIVATING 1961 MEMOIR GETS ITS FIRST ENGLISH TRANSLATION

By Andrew Nodell

Art curator Rose Valland was an unassuming hero. After receiving degrees in art history from the École du Louvre and the Sorbonne, she became a volunteer assistant curator at the Jeu de Paume museum in France in 1932. Within a year, the Nazi Party rose to power and Valland’s now historic trajectory was set in motion. Throughout the next decade, Adolf Hitler’s grasp at European domination threatened all aspects of human life, including cultural identity.

Valland, André Dézarrois and an unidentified attendant at the Jeu de Paume museum in 1935. Photo credit: Archives nationales, France, 20144707/289 (box no. 1)/Monuments Men and Women Foundation.

When German troops invaded and defeated France in the summer of 1940, it became clear to Valland that her country’s rich and precious cultural heritage was in peril. Modest in appearance and demeanor, Valland gained the trust of Nazi officers, who allowed her to act as custodian of the Jeu de Paume’s treasured galleries, where Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg (ERR) – the organization responsible for systematic looting during the occupation – stored the books, manuscripts, jewels and fine art it plundered, including Johannes Vermeer’s The Astronomer. Little did the Nazis know at the time, this astute academic was risking her life to covertly document the inventory and movement of these cultural treasures in the hope they would someday be returned to their rightful owners.

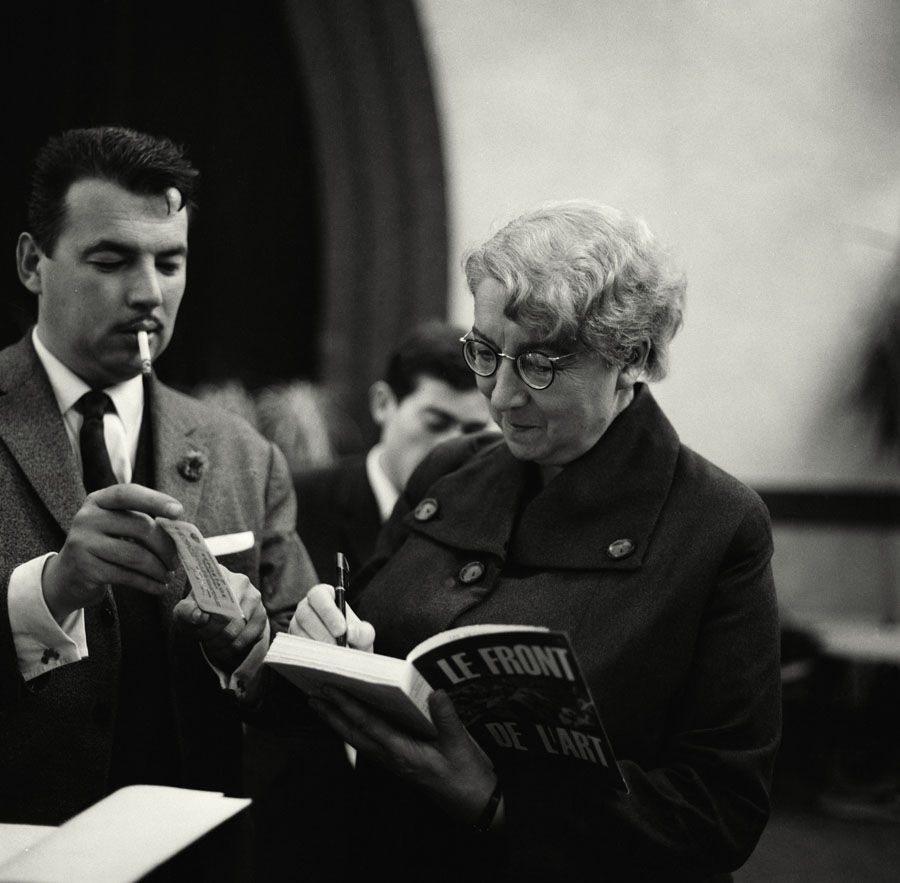

Valland remained vigilant throughout the war, and because of her efforts, tens of thousands of artworks and culturally significant objects were recovered after the fall of the Third Reich. She later became a captain in the French military and, for her heroism, one of the most decorated women in French history, documenting her saga in a 1961 memoir titled Le front de l’art.

Enlarge

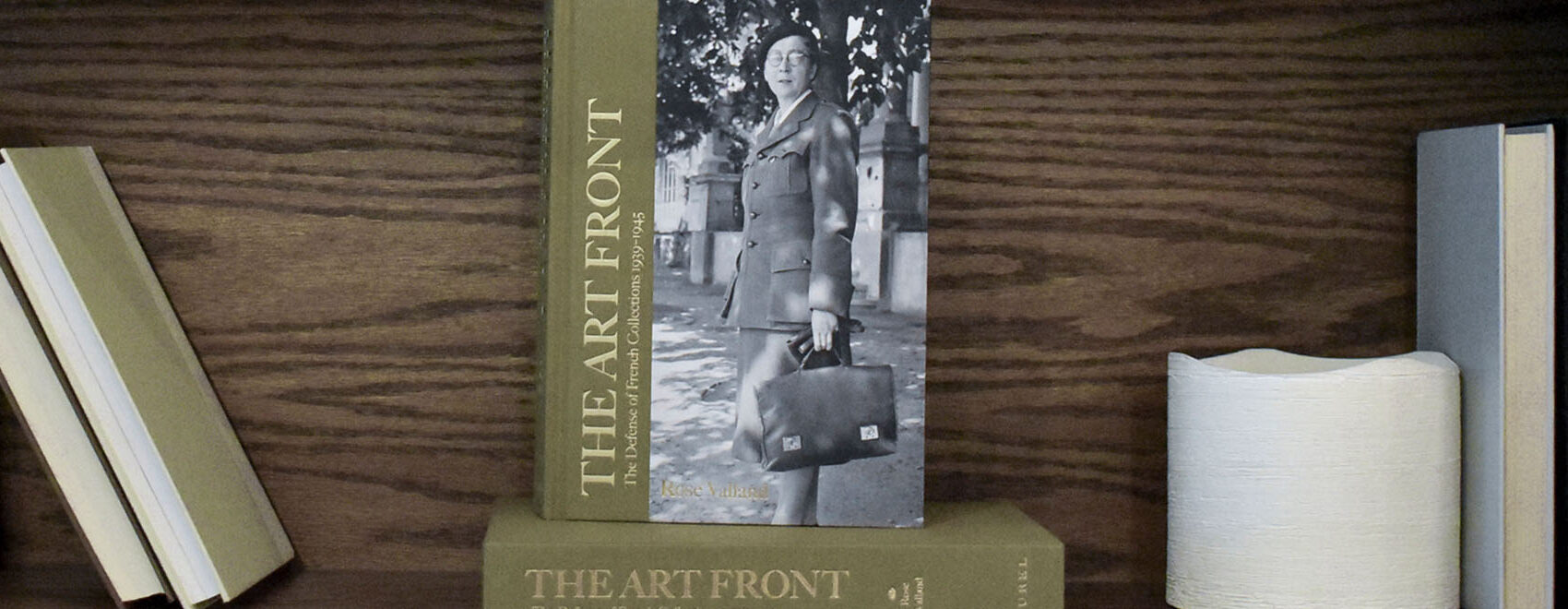

Valland signing a copy of her 1961 memoir ‘Le front de l’art.’ Photo credit: akg-images/Paul Almasy/Monuments Men and Women Foundation.

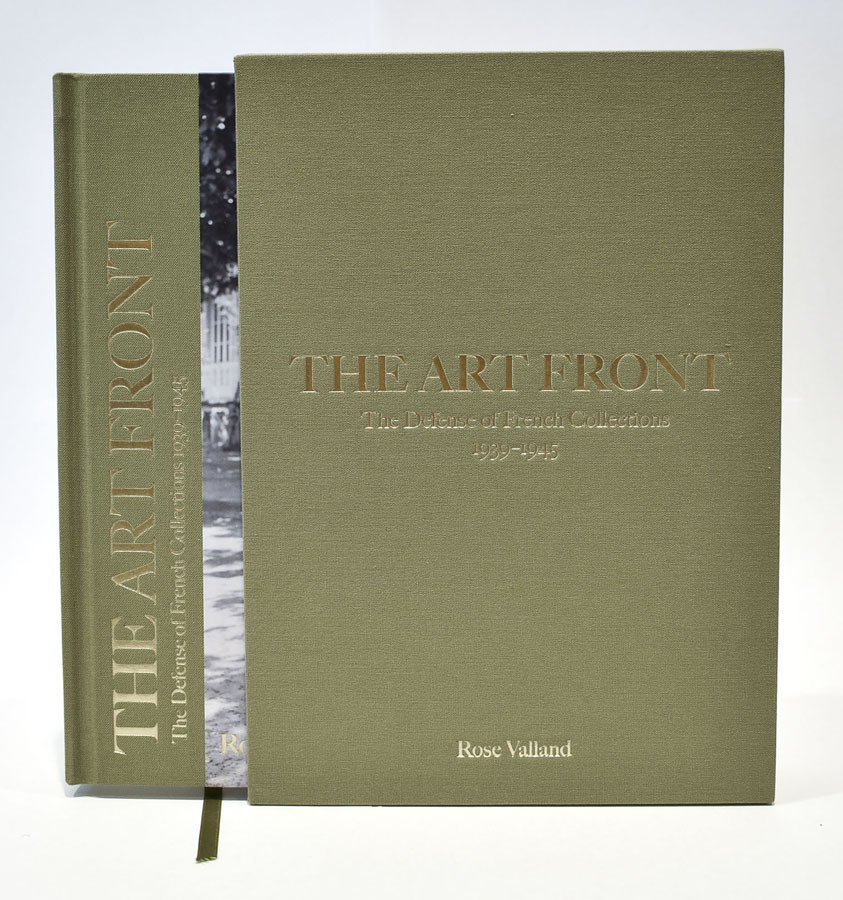

But only now has an English translation of the book become available, through the dedicated work of the Monuments Men and Women Foundation, a Dallas-based organization dedicated to preserving and protecting cultural heritage. Titled The Art Front: The Defense of French Collections 1939-1945 and translated by art historian Ophélie Jouan and the team of experts at the Foundation, this newly released limited-edition translation of Valland’s text includes source documents, period photographs and ample footnotes to guide the modern reader through her eyewitness account of Nazi looting. But for someone so instrumental in the cultural preservation of Europe, why has Rose Valland’s name remained largely unknown to global audiences?

“Men have been talked about more [historically], the women less so,” says Anna Bottinelli, president of the Monuments Men and Women Foundation. “The French wanted their wartime past to fade away in the postwar years.” Bottinelli notes that several key Nazi figures were still alive when Valland wrote her memoir in the early 1960s and “it was safer not to talk about them.” Even Valland’s account of the dramatic war years reads with a certain degree of restraint. Only once in her book does she mention by name the German art dealer Bruno Lohse, who was Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring’s art agent and a prominent participant in the Nazi looting during the war years. “He’s the one [Nazi] who, on several occasions, threatened to shoot her when they suspected that she was paying too much attention to their looting operation,” Bottinelli says.

The book’s limited-edition copies feature a fabric slipcase, gold leaf printing and a satin ribbon.

Throughout the Nazi occupation, Valland covertly made detailed notes of art transfers, which were largely executed under the illusion of legality and often came from the collections of prominent Jewish collectors. This fraudulent credibility on behalf of the Third Reich ultimately aided in postwar restitution efforts. “There are receipt slips of payments [for works bought by the Nazis], but then you look at the bank accounts of the families, and those funds were never actually received,” Bottinelli says. “They recorded the amount that was decided upon, who was going to pay and where the funds were going to go. It’s just that the money was never actually sent. And the rightful owners would never have agreed to sell these works anyway.”

With exacting German precision, each work was carefully documented, a system that ultimately backfired for the Third Reich after the war. “There was a paper trail for the majority of objects, which is why so many works of art were able to be returned to their rightful owners,” Bottinelli adds. “It was this attempt at creating a veneer of legality that then provided the map to operate the theft in reverse and return the works of art.”

Monuments Man Captain Walter I. Farmer with Valland and Monuments Woman Captain Edith A. Standen. Photo credit: Private collection/Monuments Men and Women Foundation.

According to Bottinelli, Hitler’s fascination with amassing an “important” art collection was initially inspired by a 1938 visit to the Uffizi Galleries in Florence at the invitation of Italian dictator Benito Mussolini. As his reign of terror spread across the continent, Hitler commissioned his henchmen at the ERR to procure great works that the Führer deemed important, which were primarily Old Masters and Renaissance masterpieces. The dictator’s grand vision for these works was the so-called Führermuseum, an unrealized museum in his hometown of Linz, Austria, that he intended to use as a showcase of Teutonic superiority.

The Nazis pillaged works from prominent collectors and targeted Jewish family collections, including the Rothschilds, David-Weills and Friedmanns. However, works by Jewish artists and those by Abstractionists and Expressionists including Pablo Picasso, Salvador Dalí and Marc Chagall were deemed “degenerate” and either used as currency to pay for the Nazi war machine or were destroyed, despite Valland’s best efforts to thwart destruction. She writes of witnessing a sobering scene in July 1943 when “a column of smoke kept streaming up from the terrace of the Tuileries Garden” as “modern paintings, about five or six hundred, were burning in the very heart of Paris. All had been designated by the ERR as ‘unusable’ and dangerous. In them was a poison that had to be destroyed: the Jewish inspiration the Führer had denounced.”

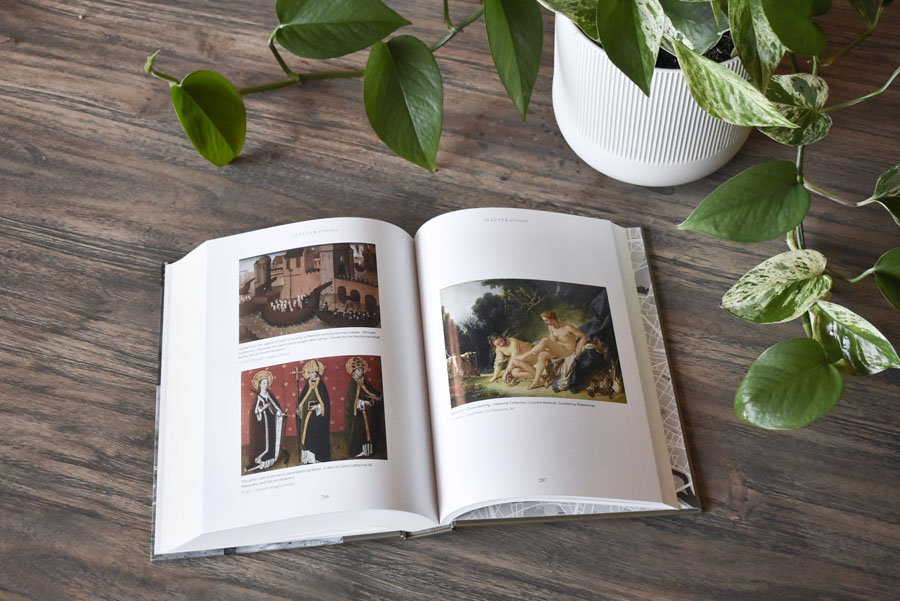

The book includes more than 100 photographs, many of them showing the looted artworks that passed through the doors of the Jeu de Paume. Photo credit: Monuments Men and Women Foundation.

But for every work that was destroyed, dozens of others were recovered thanks to Valland’s singular efforts. “She was the only person on the inside to witness in detail what the Nazis were doing,” Bottinelli says. A notably epic scene in her text occurs in August 1944 when, as Allied troops were days away from liberating France, train cars were loaded with 148 crates containing “degenerate” works by Paul Cézanne, Claude Monet, Edgar Degas, Amedeo Modigliani and Pierre-Auguste Renoir, among others. Because Valland was able to record the rail car numbers on the Jeu de Paume’s shipment logs, the train was tracked and ultimately liberated by French troops, saving the irreplaceable works from theft and possible destruction.

“Had the train been able to reach its destination of the castle of the Prince of Dietrichstein in Nikolsburg, one could assume that these works of art might have been destroyed all the same, since that storage location was entirely wiped out in the last days of the war,” Valland writes. Her account of this intense series of events was later dramatized in the 1964 film The Train starring Burt Lancaster and Jeanne Moreau.

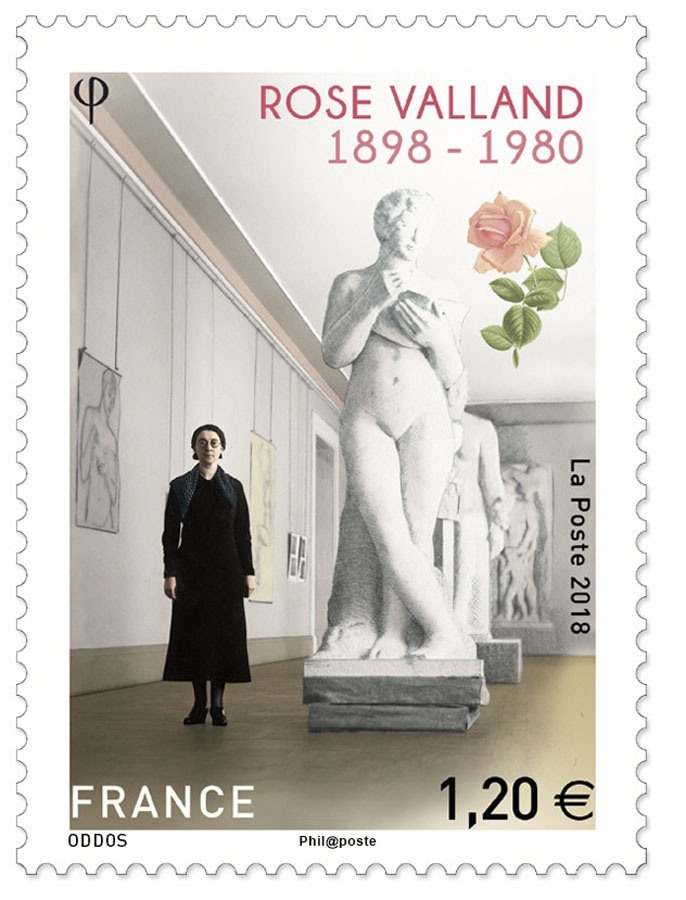

For a limited time, those who order a limited-edition copy of ‘The Art Front’ will receive a stamp issued in 2018 by the French Post to honor Valland. Photo credit: Monuments Men and Women Foundation.

In the decades that followed the war, Valland remained dedicated to the restitution of Nazi-looted art and, despite receiving fleeting acclaim following the initial publication of her memoir, she was not widely celebrated in her lifetime before quietly passing away in 1980 at age 81. “At her funeral, there were a handful of people at most, and too few of those who should have been there to honor this lioness of the arts,” Bottinelli says.

It is the Foundation’s hope that this first-time English translation of Valland’s memories will spark far broader awareness and respect for her selfless and courageous service to cultural protection through one of humanity’s darkest hours. “As an art historian, there is nothing more special than working with the primary source,” Bottinelli says. “And in this instance, to have a chance to share the experience of this remarkable and heroic woman, in her own words, with English speakers around the world makes us both grateful and proud.”

ANDREW NODELL is a contributor to Intelligent Collector.

ANDREW NODELL is a contributor to Intelligent Collector.