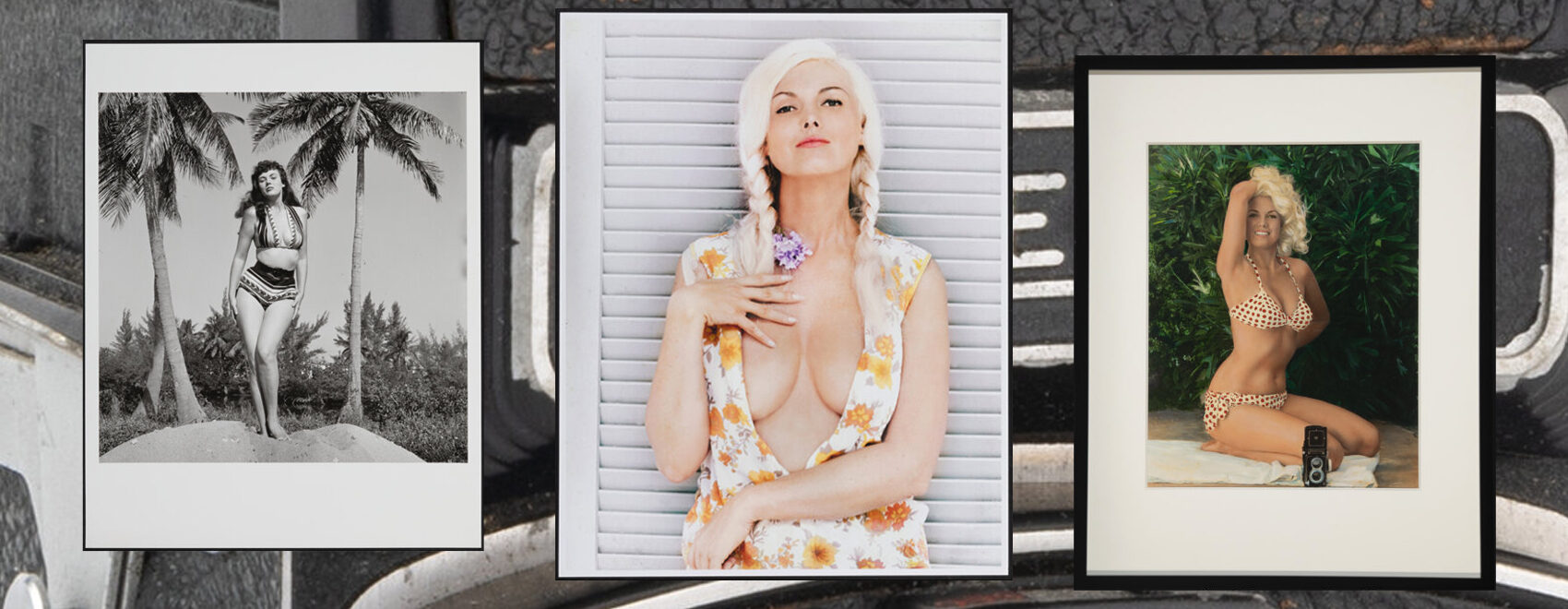

THE PIN-UP PHOTOGRAPHER’S FAMOUS SELF-PORTRAITS, HER PHOTOS OF BETTIE PAGE, HER CAMERAS AND MORE CROSS THE BLOCK THIS MONTH

By Christina Rees

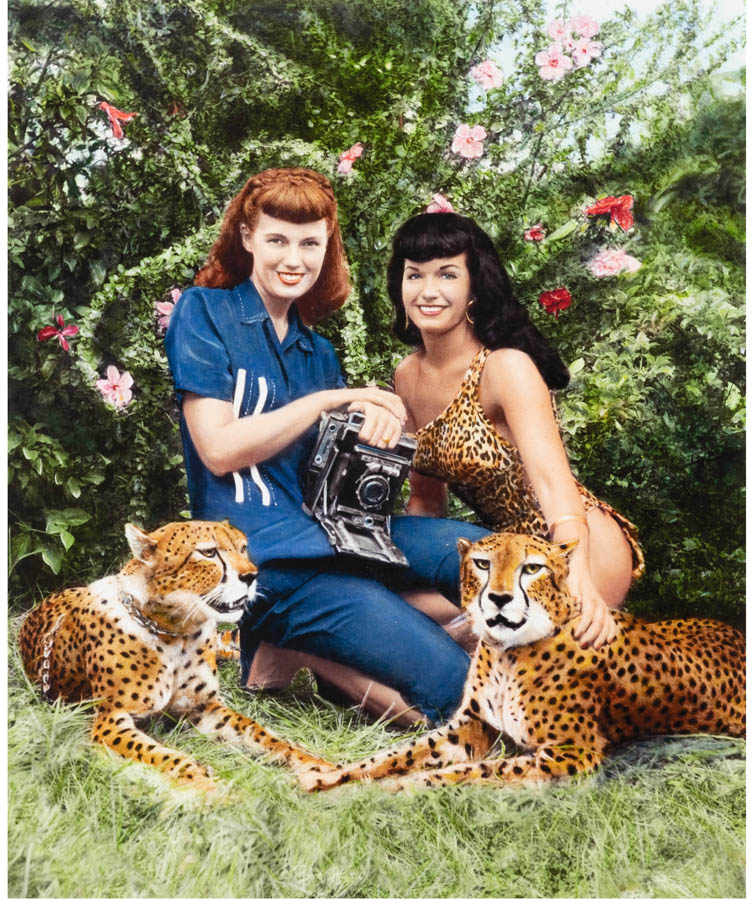

Take a look at this famous photo, included in Heritage’s October 24 The Bunny Yeager Archive: Pin Up Photographs Showcase Auction. It is arguably the world’s most famous pin-up, Bettie Page, from the 1955 centerfold shoot for the still-new Playboy magazine. Yeager took that photo in her own home, and many others of Page’s most indelible pictures, and in the process shaped the way a postwar America would frame and celebrate the female form. The notion of beauty as captured in a classic pin-up portrait could be challenged by those who fixate on the problem of “the male gaze.” But they’d have missed the recent news cycles that have resurfaced the name Bunny Yeager – one of the most successful and sought-after photographers of pin-up girls (herself a popular pin-up model) in the 1950s and ’60s, as well as a visionary behind the original aesthetic and even philosophy of Playboy.

“This shoot was life-changing for both artist and model,” says Sarahjane Blum, Heritage’s Director of Illustration Art. “Yeager sent the photos to Hugh Hefner, who had just recently started Playboy. Yeager told an interviewer, ‘Nobody had heard of Hugh Hefner, but I figured because [Playboy was] new they might pay attention to an amateur, and that’s what happened. If I hadn’t made that early connection when he was just starting out, maybe I wouldn’t have got such a big push, but immediately I became employable.’”

This photo and a trove of other significant photographs by Yeager will hit the block at Heritage just as an acclaimed documentary about the photographer continues to unspool on the film festival circuit. The doc, Naked Ambition: Bunny Yeager, takes a comprehensive look at the career of a hard-headed, fascinating artist who lived and worked in Miami, was happily married with kids, and forged her unlikely and entrepreneurial career during the buttoned-up Eisenhower years, when women weren’t encouraged along such adventurous pathways.

“At the height of her career, Yeager was a national celebrity,” Blum says, “appearing on game shows, teaching Sammy Davis Jr. how to shoot his own pin-up photography, hosting lavish galas for the South Florida arts community and explicitly setting standards for feminine allure through her popular series of photography manuals. She was an ambassador for glamour photography and Miami itself.”

Yeager’s name reappears as conversations continue to evolve about women, their agency and who defines the feminine image. Yeager, who died in 2014 after five decades behind the lens, was a decisive and ambitious artist who knew how to work with female models – including her outings with Page – in order to get the most beguiling or disarming or luscious shot. She liked shooting outdoors, she liked nature and natural light, and she liked a kind of spontaneity that allowed her models to relax and enjoy the process. She found some of the first centerfolds for Hefner (and appeared in the pages of Playboy herself) and encouraged the magazine’s early embrace of a “girl next door” ideal – the appeal of a woman who could be your own wife or neighbor disrobing simply for the innocent fun of it.

Yeager wasn’t limited: Her photography appeared in Esquire, Cosmopolitan, Women’s Wear Daily and other major national publications. She took the famous still images of a bikinied Ursula Andress emerging from the ocean in the 1962 James Bond feature Dr. No. Her vintage photographs of models (and her self-portraits) still vibrate with a sense of discovery and bright energy; Yeager loved her job and knew she was very good at it.

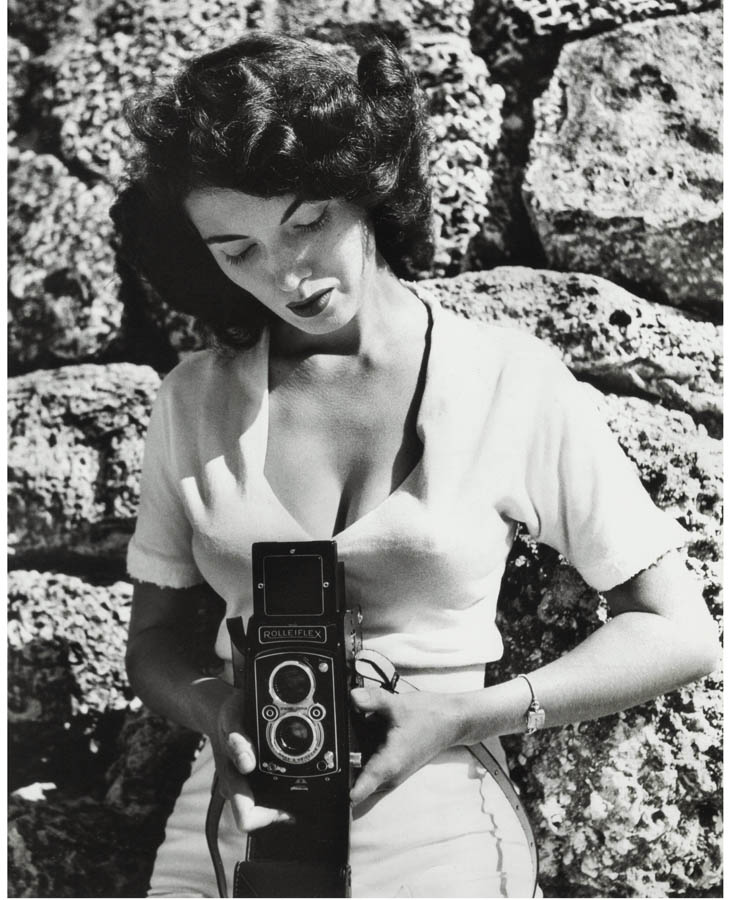

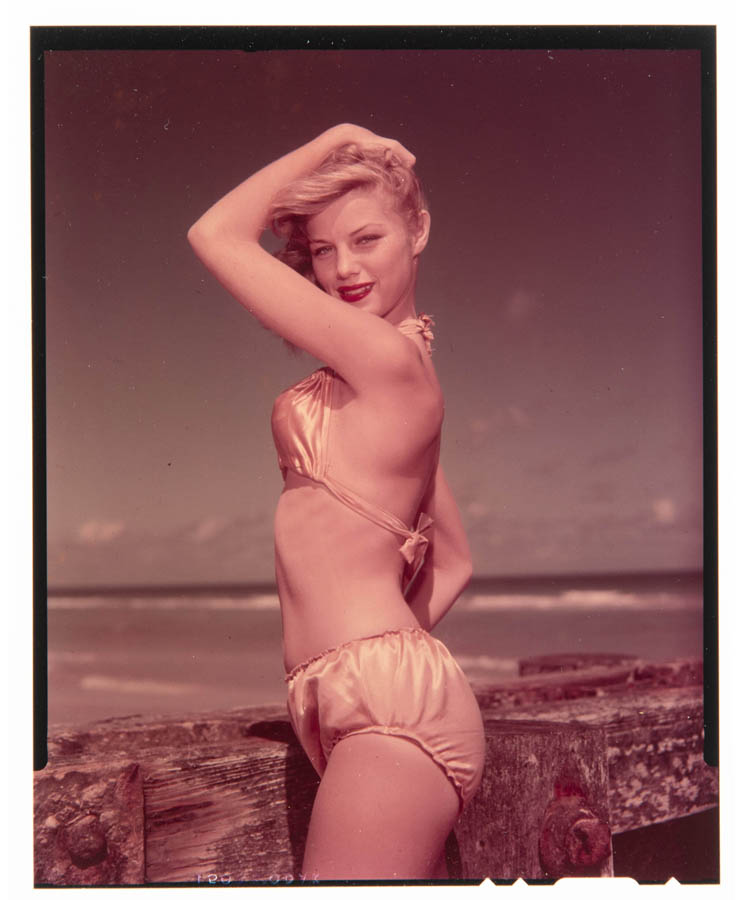

Yeager’s star only started to fade when she balked at the more explicit content demanded by the 1970s milieu – Hustler and Penthouse and the emergent skin-flick industry – and her later years were spent holding together the remains of a once-bustling career. But while she was still alive, the quality of her work demanded a reassessment and her legacy took on new meaning. “Toward the end of her life, Yeager found the critical acclaim that had overlooked her for much of her career with celebrated exhibitions at galleries in Florida and beyond and a museum exhibition at the Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh,” Blum says. “For these, Yeager reapproached her earlier work as works of fine art, creating museum-quality exhibition-sized prints, such as Nude Hugging Knee from the 1960s.” In this and many cases, Yeager’s images transcend their commercial cheesecake roots and evoke the feel of Ruth Bernhard or Alfred Stieglitz compositions. Her earlier days as an in-demand model had given her tremendous insight on how the camera lens relates to the human body, and she brought her killer instincts to every shoot. There’s a tantalizing and direct intimacy and spontaneity in this boudoir photo of Page, in this photo of Yeager’s unnamed friend leaning against a door, in this early self-portrait of the arched-eyebrow Yeager.

The relative innocence of these images was a hallmark of the era’s pin-ups but also of Yeager’s instincts to grant the medium some good intentions. In the 1970s, when she was brought up on obscenity charges, which were later dismissed, she had been pushing her work past her own comfort zone to keep up with the times, but as she put it, “They had girls showing more than they should … The kind of photographs they wanted was something I wasn’t prepared to do.”

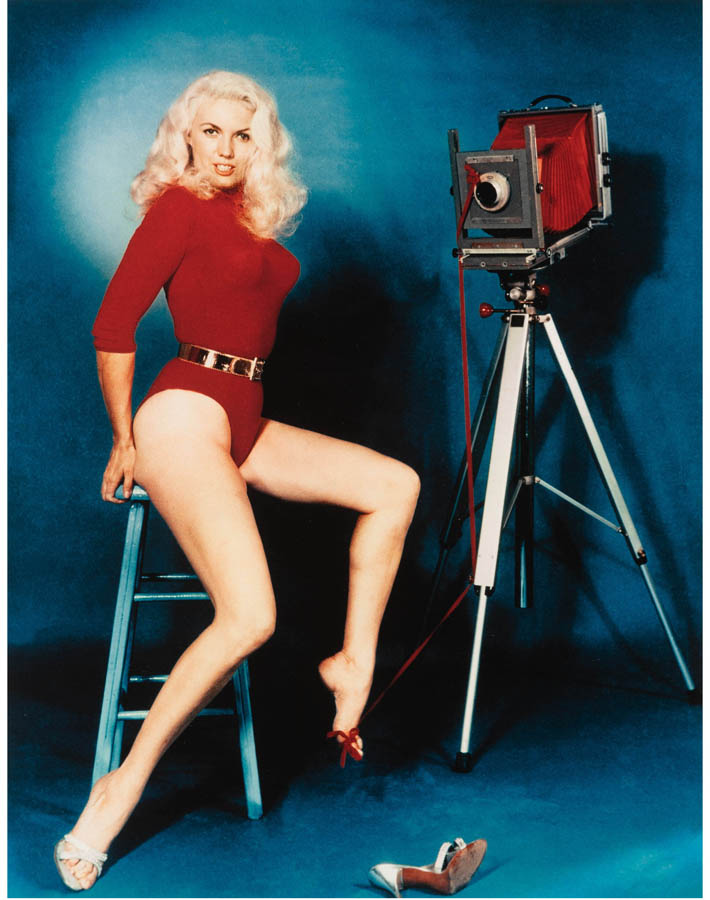

The work in this auction represents a stellar cross section of Yeager’s visions of her models, herself and the tools she used to shoot. Some self-portraits of Yeager have become as iconic as her photos of Page (some of the best of those are here, including from the famous shoot with the cheetahs) and Yeager collaborators Dondi Penn and Maria Stinger. After all, Yeager is a striking subject, and she often included her camera in the picture. Here she is as a brunette in a meta-shot, confidently setting up a theoretical shot; this image has subsequently become a photography connoisseur favorite. Here she is as a confrontational blonde pairing off with her tripod-mounted Burke & James large-format camera. And here, also offered in the October 24 auction, is her Burke & James camera.

“There is no piece of equipment more associated with Bunny Yeager than her Burke & James 8×10 camera,” Blum says. “She favored the piece for her Playboy centerfold shoots – if this camera could talk! – and featured it in the self-portrait on the cover of her important 1963 book How I Photograph Myself. The camera is on display in a number of photographs in this sale.”

The camera is joined in this auction by her circa 1950 Rolleiflex 3.5 twin-lens reflex camera (“Yeager considered the moment she was able to afford this Rolleiflex a signifier that she was indeed a professional photographer,” Blum says), as well as contact sheets from her photo shoots, materials from book manuscripts (she was a prolific author of photography books), a signed Bettie Page model release form from 1954 and props from Yeager’s studio. There are also, of course, some of her most memorable photographs, including outtake photos of Andress on the set of Dr. No; a gorgeous photograph of model Alta Whipple in a bikini in which Yeager’s use of light and color make magic; a shot of a gathering of Yeager models at a Miami fire station and many more.

“Yeager once wrote, ‘When you start photographing yourself, you are going to be amazed at the things you find…,’ encouraging everyone to approach self-portrait photography as a form of personal growth and empowerment,” Blum says. “Prefiguring selfie culture, she knew that in a world defined by photography, we are always both subject and object. This knowledge drove her creatively, helped her bring the unique personalities out of models like Bettie Page, and keeps her works feeling so dynamic and resonant today.”

CHRISTINA REES is a staff writer at Intelligent Collector.

CHRISTINA REES is a staff writer at Intelligent Collector.