CIGAR-CHOMPING PHOTOGRAPHER CHRONICLED NEW YORK’S DARKEST, MOST VICIOUS SCENES

Arthur Fellig’s photographs captured the crime, grit and complex humanity of midcentury New York City. A true “nightcrawler,” Fellig earned the nickname “Weegee” because police officers joked the only thing that explained how the freelancer was at a crime scene often before cops was his use of a Ouija board.

EVENT

PHOTOGRAPHS SIGNATURE® AUCTION 8002

April 4, 2020

Live: New York

Online: HA.com/8002a

INQUIRIES

Nigel Russell

212.486.3659

NigelR@HA.com

Weegee (1899-1968) later published books and collaborated with film directors such as Robert Wise, Jack Donohue and Stanley Kubrick. In 1993, most of his photographic prints, made from his original negatives, were donated to the International Center of Photography in New York.

In 1970, an artist purchased a box of old news photos at a secondhand store in Philadelphia. They sat in a box for decades. In 2019, the gentleman searched the internet for the name stamped on the photos, Arthur Fellig, and discovered the prints were special. He contacted Weegee biographer Christopher Bonanos (Flash: The Making of Weegee the Famous), who wrote in a story for the pop-culture website Vulture that he “about fell out of my chair” when he saw the images, most dating to the late 1930s.

Bonanos, who recently won a National Book Critics Circle award for his biography, talked about the newly identified prints, a selection of which is being offered at Heritage’s upcoming photographs auction.

When you saw these prints, you nearly fell out of your chair. Why? What makes them so remarkable?

Well, for one thing, I’d been through every image in the Weegee archive at the International Center of Photography, and almost none of these pictures were represented there. So their newness to me was exciting. But more than that, these filled in a gap in my knowledge. The late 1930s, when these photographs were made, was when he was just getting on his feet as a news photographer, freelancing out of his little apartment behind police headquarters. He was learning the craft, having quit his day job, and he was not yet frequently retaining copies of his work. I’d seen a couple of these pictures in newspapers, uncredited, and in various articles and books he’d described some of these photographs. But this was way more early Weegee work than I’d ever seen amassed in one place, and quite a few of these pictures rank with his best work.

Enlarge

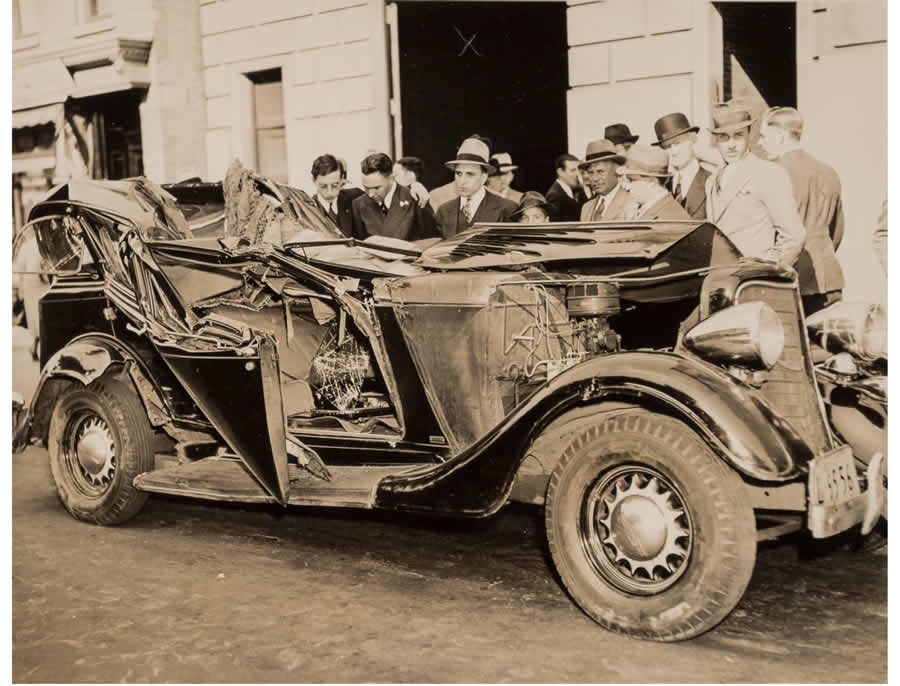

Grim Reaper Thumbs a Lift When You “Go to Town,” Car Crash, S. Portland & Fulton Streets, Brooklyn, May 17, 1937 (three works)

Gelatin silver

Estimate: $3,000-$5,000

Any idea how these prints might have ended up at a secondhand store in Philadelphia?

No idea! He used to send prints out to magazines for reproduction, so it’s possible that this was a package gone astray. Or maybe they somehow ended up in the home of a photo editor, then ended up in a junk shop after that person’s retirement or death. It’s a mystery.

Since most of Weegee’s prints and negatives were donated to the International Center of Photography, does that mean finds like this are rare?

They bob up more regularly than you’d expect. Because Weegee shot so much in his newspaper years – he claimed to work seven days a week, taking off only Yom Kippur – he made literally thousands of news pictures each year, and he didn’t treat them preciously. If he thought anyone might buy a photo, he’d print one up. Also, Weegee’s peak career was in the 1940s and 1950s, ending for good at his death in 1968, and that means – and forgive me if this is a little morbid – that his remaining friends and colleagues are mostly old people, which means many of them are downsizing or have died. So any photographs they might have kept are coming out of the attic.

These particular prints from 1937 are more unique, aren’t they? These are “work product” as opposed to prints he was selling years later.

I can’t exactly say they’re rarer, because he made so many pictures like this. But yes, these were almost surely made with the intent that they’d be sold to newspapers and syndication services the next day. They were working objects, not gallery items, and they’re well-handled, with creases and bunged-up corners. In many cases, he’s written caption information for the photo editors on the backs. There are collectors who prefer the cleaner prints he made later for people who wanted them as décor, partly because they’re often bigger and in better shape. My own preference tends to be for these prints, because they show him in his preferred idiom as a working-stiff photographer, banging out prints at deadline speed and then running out to the next job.

Enlarge

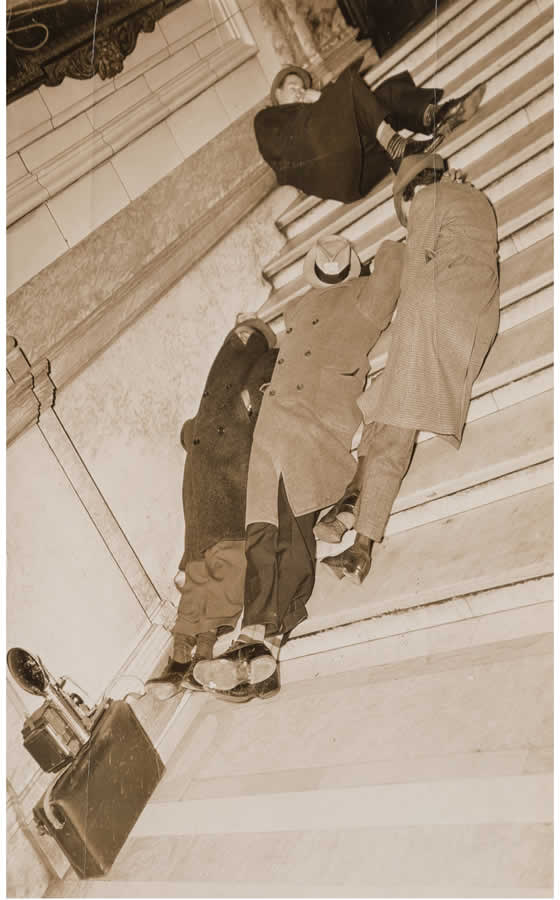

Photographers Nap on Courthouse Steps, circa 1937

Gelatin silver

Estimate: $1,000-$1,500

As Weegee’s biographer, tell us the importance or Mr. Fellig’s work. Why is he one of our most important photographers?

I could talk about this for days, but a few things come to mind. He was peerless at showing us the darkest and most vicious part of city life, yet he managed to do it with a certain playfulness — sometimes gallows humor, sometimes a dose of sentimentality — that made it all palatable. Somehow, you cover your mouth to stifle a horrified chuckle as you look at his murder victims. He was also, in his nonpolitical way, an activist, showing rich and middle-class people how the other half lived. And above all, he had a great eye — for juxtapositions, for contrasts, for composition. There’s a photograph I love in which a factory building is burning down, enveloped in steam from the firehoses, and on the facade you can just make out an advertising sign through a gap in the plumes of smoke that reads SIMPLY ADD BOILING WATER. Turns out that the building was, of all things, a bouillon-cube factory.

Christopher Bonanos will be giving a presentation, “The Lost Weegee Crime Photographs and the Man Who Made Them,” on Thursday, April 2, 6 p.m.-8 p.m., at Heritage Auctions, 445 Park Ave. in New York. Please RSVP to 212.486.3730 or RSVP@HA.com.

Christopher Bonanos will be giving a presentation, “The Lost Weegee Crime Photographs and the Man Who Made Them,” on Thursday, April 2, 6 p.m.-8 p.m., at Heritage Auctions, 445 Park Ave. in New York. Please RSVP to 212.486.3730 or RSVP@HA.com.

Enlarge

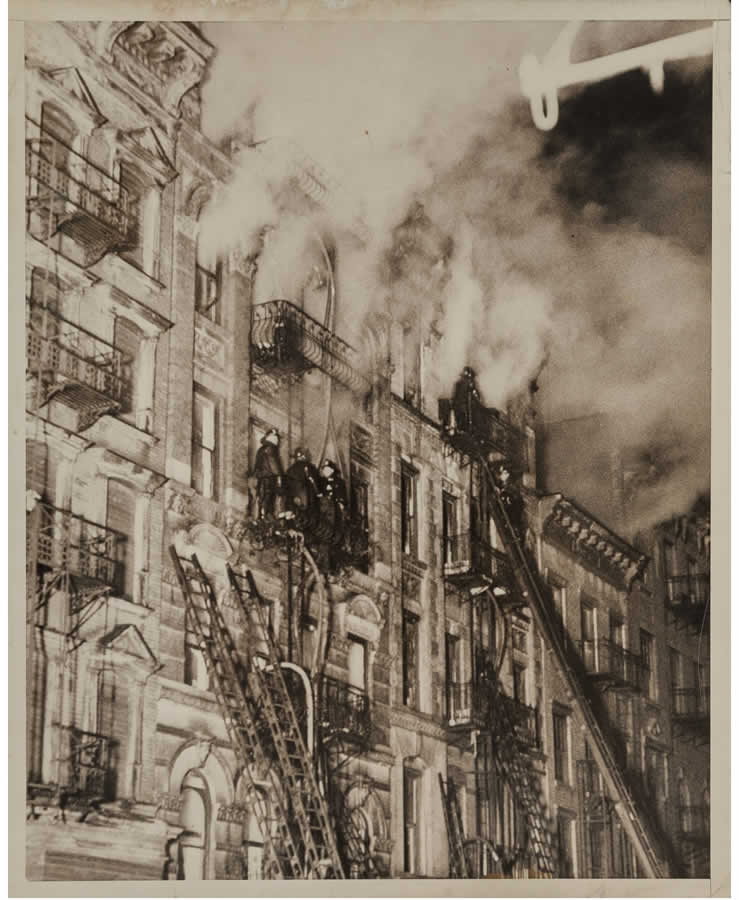

Triboro’s Baptism of Blood, New York, May 18, 1937

Gelatin silver

Estimate: $2,000-$3,000

Enlarge

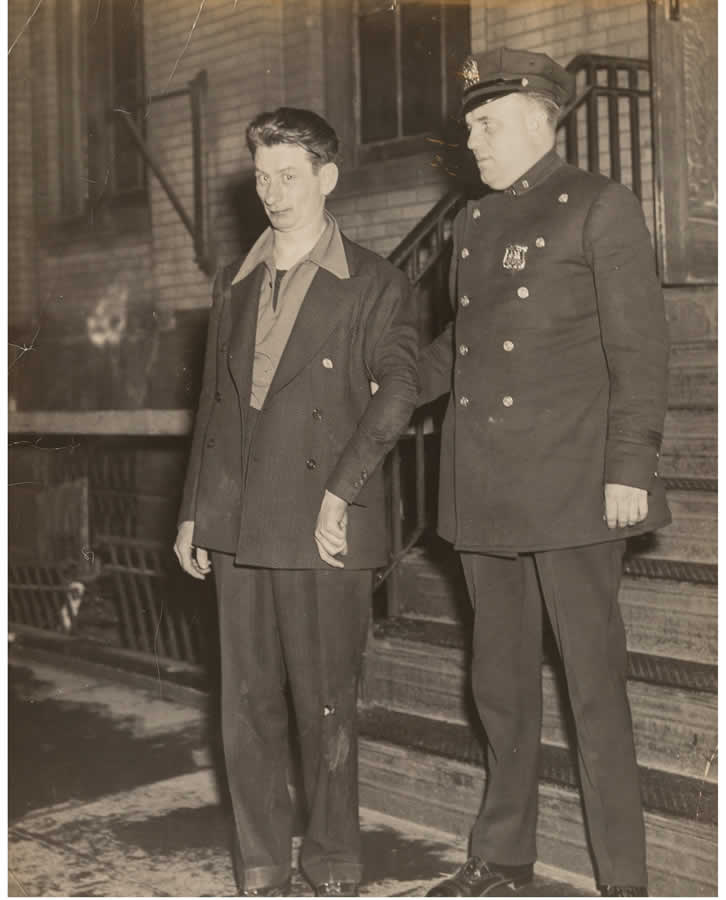

Spurned Suitor Clubs Violinist to Death, New York, April 19, 1937

Gelatin silver

Estimate: $2,000-$3,000