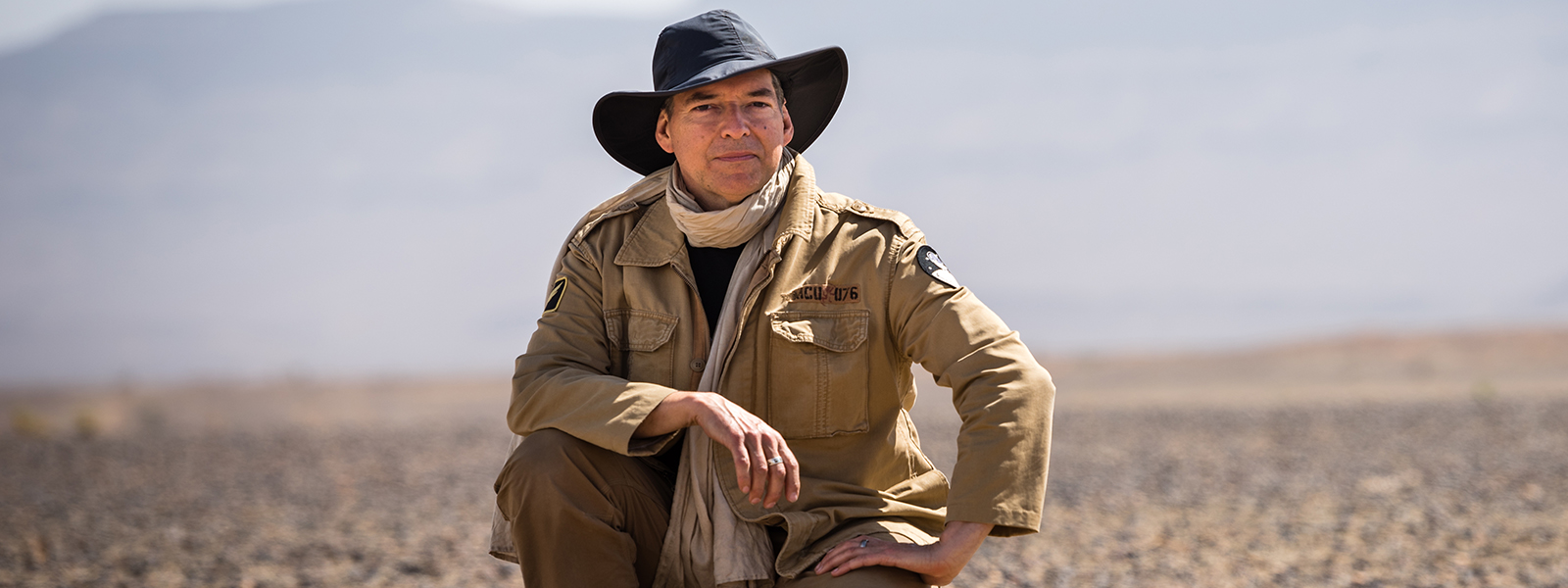

THE COLLECTOR, ADVENTURER AND SPACE ROCK CONNOISSEUR SHARES THE INSIDE STORY ON SOME OF HIS OUT-OF-THIS-WORLD TREASURES

Star of the hit television series Meteorite Men, Geoff Notkin has traveled to six continents in search of meteorites in some of the world’s harshest environments – from the Arctic Circle and Siberia to the Australian Outback and Chile’s Atacama Desert. “Somehow, the best meteorites often seem to lie in the most difficult-to-get-to places,” he says. But Notkin’s efforts haven’t been for naught. Along with leading his company Aerolite Meteorites to international renown, Notkin has amassed a world-class collection of meteorites and related items.

Enlarge

Last summer, Heritage Auctions presented a portion of Notkin’s assemblage in a 136-lot event featuring an assortment of rare, unique and collectible specimens from the collector, adventurer and meteorite hunter. Now Heritage is gearing up for the sequel. Meteorites From the Geoff Notkin Collection Part 2, offered in Heritage’s July 22 Nature & Science Signature® Auction, consists of top-quality examples of iron, pallasite, mesosiderite and stone meteorites, as well as superb specimens of lunar meteorites and exquisite impactites and other related materials.

METEORITES FROM THE GEOFF NOTKIN COLLECTION PART 2 NATURE & SCIENCE SIGNATURE® AUCTION 8116

July 22, 2023

Online: HA.com/Notkin

INQUIRIES

Craig Kissick

214.409.1995

CraigK@HA.com

“Notkin is an international authority on meteorites, and his collection is unlike any other that has been brought to auction,” says Craig Kissick, Heritage’s Vice President of Nature & Science. “The quality, uniqueness and singular nature of each offering make this auction something truly special.”

In advance of the auction, we asked Notkin to give us behind-the-scenes details on some of his favorite pieces crossing the block.

Vintage Fisher Labs 1266-X Metal Detector

A television star and Notkin’s favorite meteorite-hunting machine for many years, with original Fisher hard-shell case and a signed copy of Notkin’s book How to Find Treasure From Space, in which the unit is pictured

“My father bought me my first metal detector in 1971. I was 10 years old. It was a low-tech thing made of plastic tubing with a simple on-off switch. Basic? Sure, but I loved that thing, and together we went into the hazardous, mud-slipping River Thames at low tide, and forests surrounding Royal Air Force bases that had been bombed relentlessly by the Luftwaffe only 25 years before. The concept that I could find buried history underground by – essentially – waving a magic wand over it had me hooked hard and permanently. Most detectorists search for precious metals, not rusty bomb fragments, so when I got serious about meteorite hunting in the 1990s, I encountered a major technical obstacle. Detectors were being built specifically to ignore iron. A modern detector would cold-shoulder barbed wire, nails, horseshoes, bolts, old batteries and a billon other ferrous human discards, while a gold nugget or a hoard of Roman silver coins would sing out, ‘Here I am!’ Since meteorites are rich in iron, I needed a detector that was the exact opposite of standard – a bit like me, really. I discovered my redeemer on a Civil War relic hunter’s forum. ‘That blasted Fisher 1266!’ the frustrated relic hunters would gripe. ‘I dug down 13 inches for a rusty piece of iron.’ This was it, but finding a 1266 was no cakewalk. They were no longer manufactured, and as soon as a used model appeared on the market, it was whisked off to Cambodia to hunt for unexploded mines – something else the 1266 is very good at! When I finally did get one, it hummed like an angel. On its first real outing I found multiple buried stony-iron meteorites at Glorieta Mountain, New Mexico, while filming Travel Channel’s The Best Places to Find Cash & Treasures, which many see as the first real meteorite hunting show. I used it on the PBS Wired Science pilot and again on my Meteorite Men pilot. Fisher Labs was so delighted and surprised to see a 1266 on Science Channel that they reached out to me and did a complete refurb on what was then a legacy unit. The very issue that made the 1266 anathema for relic hunters made it a dream for this meteorite hunter. This 1266-X has found many beautiful space rocks and is a TV star, too! Give it a good home for me.”

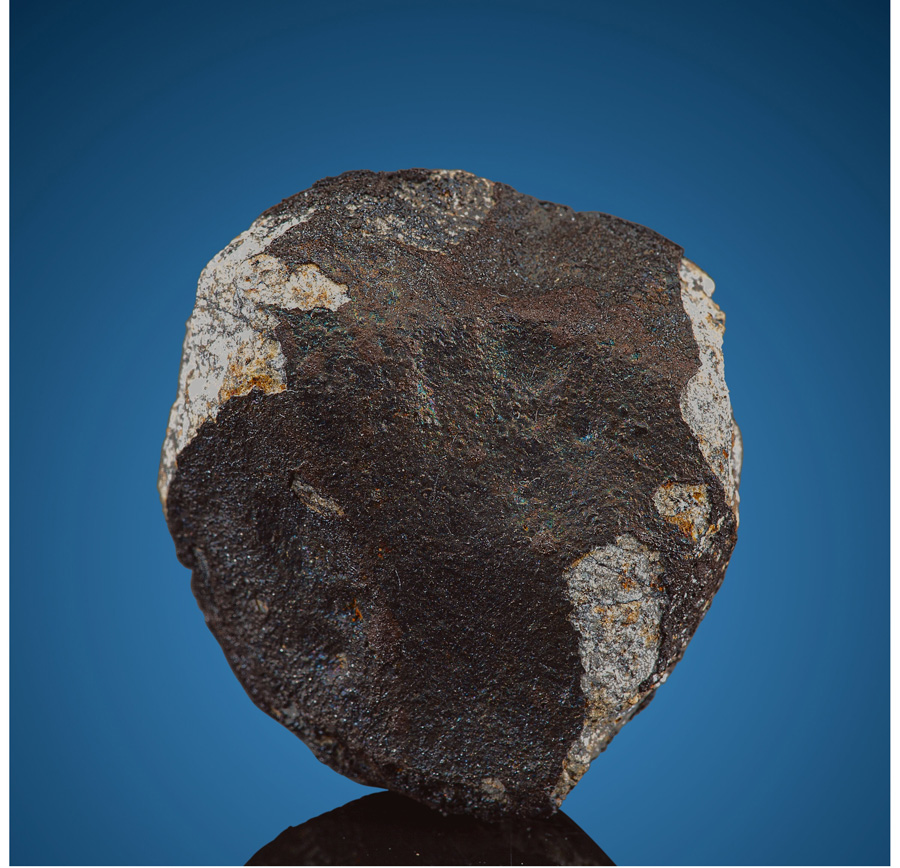

Park Forest Meteorite

A complete Park Forest stone meteorite from the celebrated Chicago fall of 2003, found by Notkin in a parking lot and featured in How to Find Treasure From Space

“As an adventurer, science writer and professional meteorite hunter, roughing it and dining army-style is just part of one’s normal existence. Eating beans out of a can in the Australian Outback, chewing on a stale empañada in Chile’s Atacama Desert and slurping eel soup with flies in Siberia become almost normal. Except that one time. On March 26, 2003, hundreds of stone meteorites fell on the south suburbs of Chicago, Illinois. I flew to O’Hare Airport and met my hunting buddies Steve Arnold (later to join me on Meteorite Men) and John Sinclair. When a significant meteorite fall occurs, there are typically numerous tiny pieces at ‘the small end’ of the fall zone (or strewnfield), some medium-sized in the middle, and one or two whoppers at ‘the big end.’ The other meteorite hunters had converged at the big end, where one space rock went right through the roof of a house. We three did the opposite and hit the small end; we’d rather find numerous small meteorites than maybe one big one. And we did: on a baseball diamond, on the flat roof of an industrial building and dead in the middle of a busy road, which caused me to run into speeding traffic – because it was a meteorite lying there after all! For the first time ever, we were hunting in an urban area. Instead of opening another can of beans for lunch, we went to a nice restaurant and proudly displayed our finds on the table, to the bemusement of our server. Then it started raining. The delicate fusion crust on meteorites will corrode quickly in moisture, so we adventurers bought three mountain bikes and zoomed like comets across the slippery, open spaces of South Chicago. My best find (pictured on page 59 of my book How To Find Treasure From Space) was a glorious freshly fallen stone of 21.6 grams, just waiting for me in the rain in a parking lot. It was my largest Park Forest find and the best meteorite I ever found in a major city, proving that space rocks really can fall – and be found – just about anywhere!”

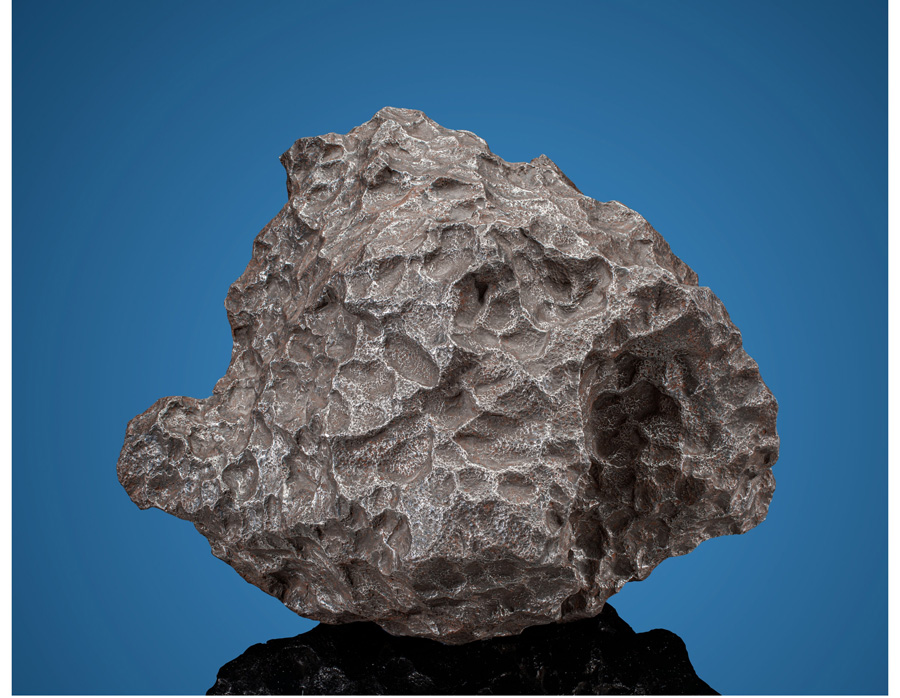

Campo del Cielo Meteorite

A giant iron meteorite with marvelous visual features to rival many a museum display

“In nearly 30 years as a meteorite finder and vendor, I have handled literally thousands of space rocks, from the tiny to the scientifically fascinating to the historically important to the overwhelmingly massive. Out of all of them, this was the best. Weighing nearly 68 kilograms (150 pounds), it is, for me, the epitome of an iron meteorite. It was reportedly found buried 12 feet underground using a massive, wheeled metal detector and then hoisted from the dark with a makeshift block and pulley. When an iron meteorite hurtles through our atmosphere it often acquires little indentations called ‘thumbprints’ or, scientifically, regmaglypts. These features are unique to meteorites and give them a sculptural aspect. This magnificent specimen is nearly covered in them, and it is also oriented, meaning some of its leading edge ablated during flight, giving it a rounded or nosecone-like aspect. Oriented meteorites were studied by early spacecraft designers and remain fascinating to collectors as their very shape has been altered by their fiery journey toward planet Earth. Many years later, my wholesaler visited my house, saw this piece and was so smitten with it he tried to buy it back. I declined. Of the scores of very large meteorites that had passed through my company, this is the one I chose to keep. It was the centerpiece of my private collection for decades and the centerpiece of my home, sitting, as it did, on a modest pedestal, often admired by visitors and also my cat. The single finest piece in the Notkin Collection of Meteorites, it is a masterpiece of cosmic engineering and will delight and enthrall its new owner for light-years to come.”

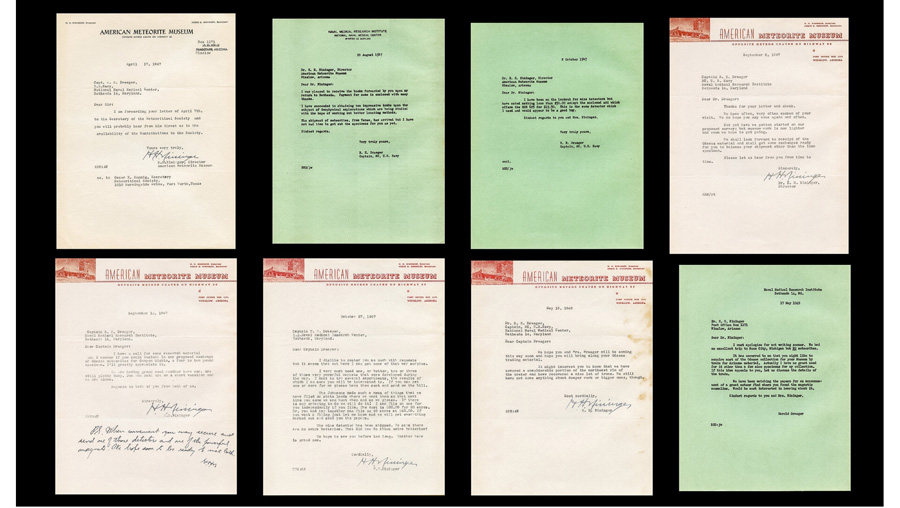

Harvey H. Nininger Letters

Extraordinary set of original correspondence between H.H. Nininger of the American Meteorite Museum and fellow meteorite hunter Captain R.H. Draeger

“Harvey Harlow Nininger was a giant in meteorite science. From his modest start as a high school biology teacher in Kansas, he went on to found the American Meteorite Laboratory, the American Meteorite Museum and the Meteoritical Society (still the preeminent body today). He also recovered thousands of meteorites, educated a generation about space rocks and carried out critically important seminal work at major sites such as Meteor Crater in Arizona. Nininger’s fans, of which I am one, refer to him reverently as ‘The Godfather of Meteorite Science.’ His son-in-law, Glenn Huss, and grandson, Dr. Gary Huss, have carried on his work in a generation-spanning dynasty of meteorite scientists. Nininger painted delicate collection numbers on his specimens, and any meteorite with such figures increases greatly in both financial and historic value. Nininger was a vigorous author of scientific papers, books and letters, and decades before the internet, correspondence between scientists and researchers was not only convenient, but also provided a record of their discourse and news. From 1947 through 1952, Nininger carried out a lengthy correspondence with Captain R.H. Draeger, a U.S. Navy officer and early meteorite hunter. Using a World War II mine detector, Draeger made significant meteorite finds at the Odessa Crater near Midland, Texas. Fortunately, Draeger kept the original letters Nininger sent to him, together with carbon copies of his own replies, and I acquired all of them directly from the family. Nininger maintained his own printing press and took great pride in his American Meteorite Museum logo and typography. This devotion can clearly be seen in the beautiful vintage duotone AMM letterhead, which appears here in multiple styles. Of the 23 documents, 13 are personally hand-signed by Nininger, and one includes an additional handwritten note. This is a fascinating and totally unique glimpse into the life, work and writing of the Godfather of Meteorites and one of his colleagues.”

Seymchan Meteorite Slice

Two meteorites in one: a spectacular space gem-studded transitional Seymchan pallasite from Eastern Russia

“Ask 10 meteorite aficionados to pick the most beautiful space rock, and nine will reply, ‘A pallasite.’ Pallasites are a unique and visually dazzling group consisting of approximately 50% extraterrestrial nickel-iron and 50% olivine, which is the gemstone peridot. So, space gems! Pallasites are beyond rare. Meteorite science currently recognizes nearly 72,000 officially analyzed meteorites. Out of all of those, only 166 are pallasites! And some of those exist only as a small, single stone. When pallasites are expertly prepared in the laboratory, as this slice has been, they reveal both their complex nickel-iron crystalline structure and a wealth of space gems. Most pallasites show a fairly uniform distribution of beanlike gem crystals throughout their metallic matrix, but not this Seymchan slice from Russia. This example is a transitional pallasite in that it exhibits features of both metallic (siderite) meteorites and stony-iron meteorites (pallasites) in a single face. Such examples are extremely rare, and I have only seen a handful in my 30-year career. The original mass was found in Russia by meteorite hunter colleagues of mine. They showed me the rough mass over a video call, and I bought it immediately, little knowing what wonders it would reveal. My laboratory preparator fabricated a special diamond-tipped saw to cut it and then called with good news and bad: ‘This meteorite,’ he said, ‘is the hardest mass I’ve ever cut in 25 years in the lab. It takes eight full hours for each pass of the saw!’ The good news? It was the single finest transitional specimen he’d seen in his entire career. This slice was taken from the center of the mass and is the very best of the lot. I kept it in my private collection for many years, a constant reminder that some asteroids surrounding us – out there between Mars and Jupiter – may still be active with molten cores, much like our own planet, and capable of producing enthralling geologic wonders such as this cosmic kaleidoscope of metal and gems.”