SEATTLE GRUNGE POSTERS CAPTURE EARLY SHOWS BY NIRVANA, PEARL JAM, SOUNDGARDEN

By Eric Grubbs

What do you do when you want to promote your band’s next show, but you have no means to make a vivid poster printed on cardstock? Rather than complain, you look into a way of doing it yourself.

EVENT

ENTERTAINMENT SIGNATURE® AUCTION 7203

Nov. 16-17, 2019

Live: Dallas

Online: HA.com/7203a

INQUIRIES

Garry Shrum

214.409.1585

GarryS@HA.com

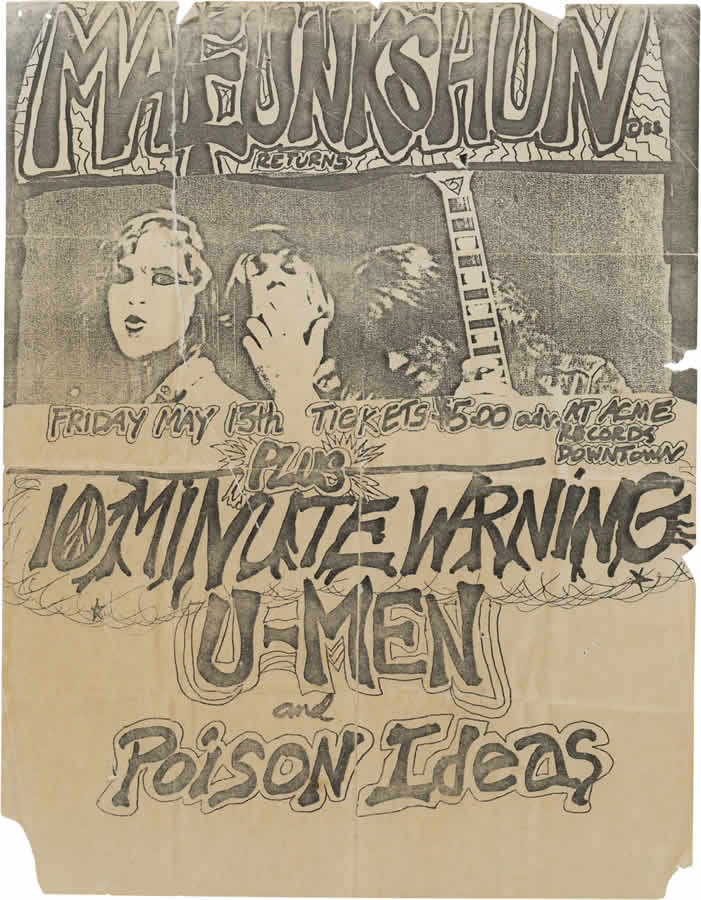

There was an aesthetic that developed with punk rock in the mid-1970s: Grab whatever you had (whether it’s a pen or pencil, with papers, scissors — and maybe a library card) and make your own poster. And if you knew someone with a copy machine, you were in business.

The punk rock aesthetic was crude, bare bones and sometimes an affront to mainstream society. For those who didn’t fit into the mainstream, this was their place to feel like they belonged. Whether it was in New York, Los Angeles, Austin or a small town nowhere near a big city, hundreds of bands formed in the wake of the popularity of bands like the Sex Pistols, the Damned and the Ramones. In turn, another wave of young bands formed that pushed the aesthetic even further. Called hardcore, this was not like the Journey or Eagles records popular on Top 40. This was raw and rough, and intentionally not for everyone. And so were the posters for these bands’ shows.

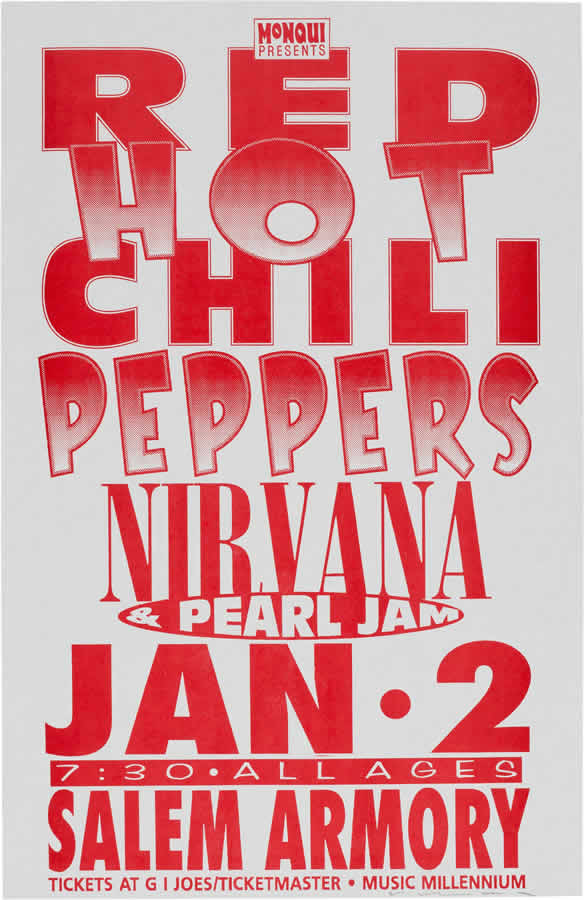

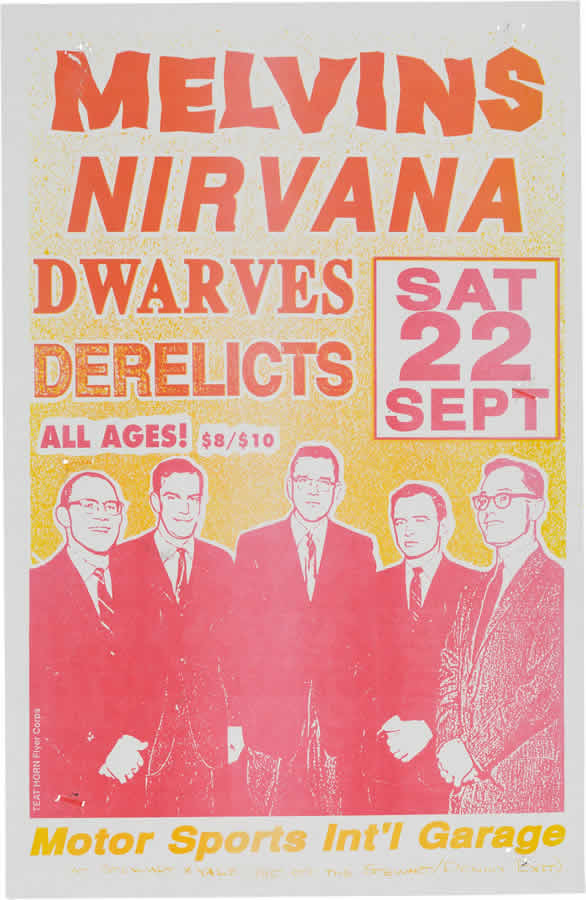

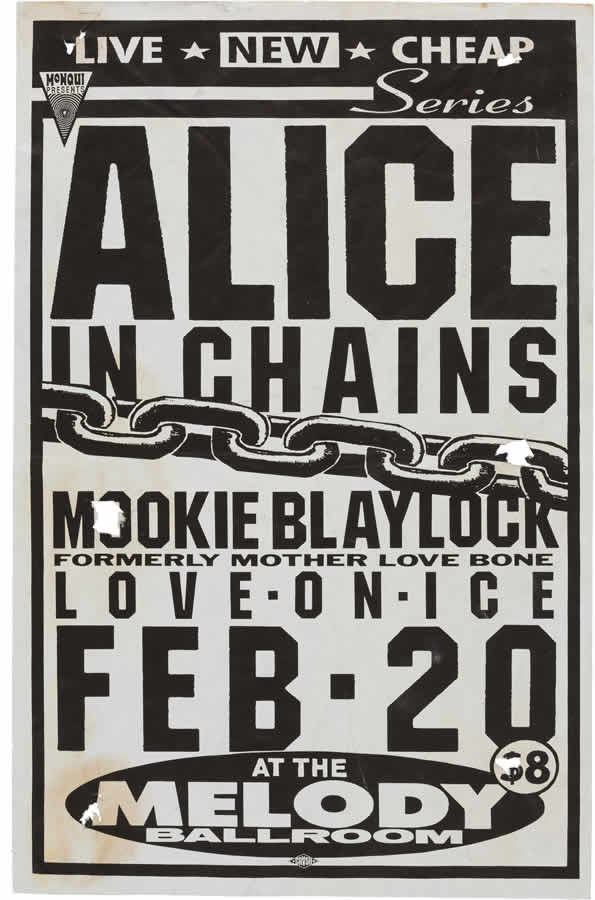

Starting in November, Heritage Auctions will offer posters from a massive collection of posters and handbills from the Pacific Northwest from the early 1980s to the early 1990s.

Before the internet, social media and cell phones, people had phone books and fan-made magazines (often called fanzines or just zines). These posters were the way to introduce people to music that was not on TV or radio. “It was a vital form of communication among these disenfranchised people,” says Art Chantry, a legendary poster designer and art director who spent many years in the Seattle area.

Artwork was a major part of the music and underground culture, in terms of showing people there was an alternative to the mainstream.

“It was more about controlling your own media,” says Michael Azerrad, author of Our Band Could Be Your Life and Come As You Are: The Nirvana Story. “So you had people making fanzines instead of passively reading Rolling Stone, which was largely ignoring this music. You had people doing college radio stations – sometimes pirate radio stations – instead of passively absorbing commercial radio, which also ignored that music. And, of course, people were making music they weren’t hearing in the mainstream.”

In and around Seattle in the mid-1980s, bands that blended punk, metal and hard rock started to make a noticeable sound that was definitely not on rock radio, or replicated anywhere else. They sounded nothing like Heart or Queensrÿche, Seattle’s biggest exports of the day. Pacific Northwest bands like the Wipers, Green River, the Melvins and Skin Yard, along with national acts like the Minutemen, Black Flag, the Replacements and Hüsker Dü, all made an impact on music fans who weren’t moved by Pat Benatar, Michael Jackson or Loverboy.

Though the word had been used before to describe a style of music, “grunge” became the name du jour for this new sound.

With bands like Soundgarden, Mother Love Bone and Alice in Chains garnering attention from major labels, it was a small band from Aberdeen – a few hours away from Seattle – called Nirvana that really brought this sound to the mainstream. Their second album, Nevermind, changed people’s minds about what could look ugly and worn down yet be accepted by the mainstream.

But the “Seattle sound” was a misnomer. The area has always had a diverse amount of music. The certain segment that was sold to kids in the suburbs was a style that looked and sounded like the polar opposite of Whitesnake, Bon Jovi and Def Leppard. Gone were intricate guitar solos and big hair. Now it was music that wasn’t technically proficient and was easy to get into, and even easy to learn to play for amateurs.

The same can be said about the posters made to promote it.

Chantry had wanted to design posters since he was a kid and he started making them in high school. Taking on projects for Nordstrom, GE and Boeing made him a livable wage, but he really wanted to make posters for his friends. During the formative years of the Seattle alt-weekly newspaper The Rocket, he was the publication’s art director. And the copy machine changed the game for everyone.

By the early to mid-1980s, copy machines were cheaper to purchase, so they weren’t relegated to large companies any more. Now there were copy machines in shops all over the country.

“The gradual accessibility of the copy machine to just about anybody was one of the things that really enabled this whole movement,” Azerrad says.

The excitement around Nirvana, Pearl Jam, Alice in Chains and Soundgarden didn’t come out of the blue. It was a tornado coming to your town and nothing could stop it.

“Nobody predicted Nirvana when that happened,” Chantry says. “When that happened, it was like a floodgate opened and this whole town caught on fire and everybody burned up. Everybody was running around with their hair on fire for about three or four years. It was a crazy time.”

Now with auction houses selling these rare posters, flyers and handbills, one has to wonder if the Seattle area is getting exploited again. For Chantry, he is honored, actually.

“The idea of selling punk as a collectible is just now coming into its own,” Chantry says. “The really rare and beautiful stuff is just going for outrageous prices.”

Chantry sees the importance of preserving stuff tied to the past. Keeping documentation is vital. Plus, according to him, auctioning off posters legitimizes the art and aesthetic.

“I want this stuff to survive me,” Chantry says.

ERIC GRUBBS is a music memorabilia cataloger at Heritage Auctions who has written for LA Weekly and the Dallas Observer.

ERIC GRUBBS is a music memorabilia cataloger at Heritage Auctions who has written for LA Weekly and the Dallas Observer.