ALAN ALDA ON WHY HE’S PARTING WITH HAWKEYE’S COMBAT BOOTS AND DOG TAGS, THE ACTOR’S SOLE REMAINING MEMENTOS FROM THE BELOVED SERIES

By Robert Wilonsky

Enlarge

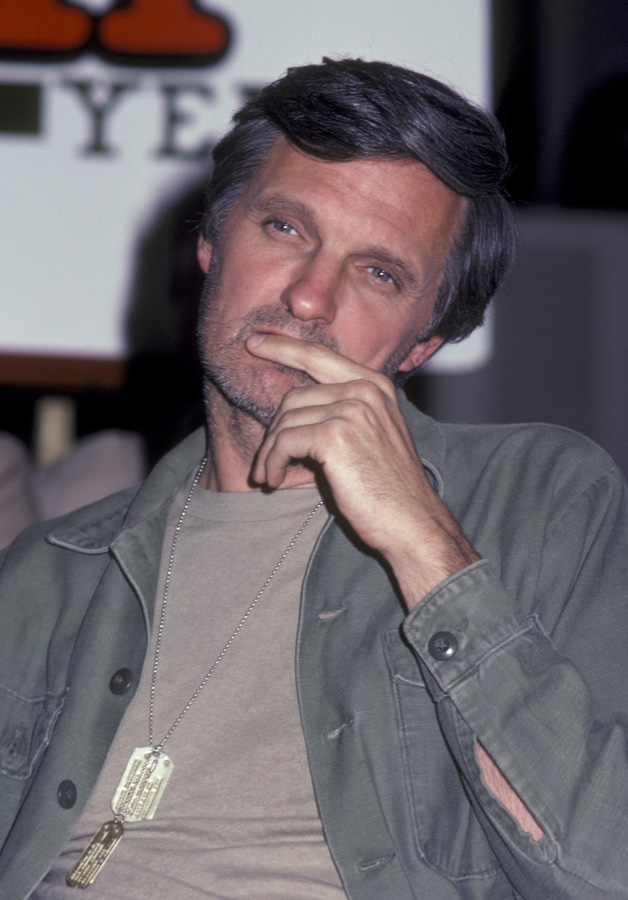

Alan Alda, then 36 years old, reported to the 4077th Mobile Army Surgical Hospital in the summer of 1972. Upon arrival, he received two items from wardrobe that became the only M*A*S*H mementos he kept upon bidding goodbye, farewell and amen to the beloved series in 1983.

Costumers handed him a pair of scuffed-up combat boots, inside which someone had written in black marker the name of his character: “HAWKEYE.” He was also given a pair of dog tags, two tiny rectangles made of nickel and copper upon which the names of strangers had been stamped: Hersie Davenport and Morriss D. Levine.

Every day, throughout 251 episodes as Capt. Benjamin Franklin Pierce, the heartbreaker and lifesaver stationed three miles from the Korean front, Alda slipped on those boots. Every day, he put those dog tags over his head. And every day, he thought about the men who had worn them before him.

“Putting on the boots and lacing up the boots, I was literally stepping into somebody’s shoes,” the 87-year-old Alda says now. “That feel of the leather on my foot, the comfort of being in those shoes, did something …” Alda pauses. “I don’t know. It’s a mysterious thing, but it makes you feel more at home in the character.”

Alda was grateful the dog tags didn’t say Benjamin Franklin Pierce of Crabapple Cove, Maine. That would have made them mere props that couldn’t have carried the weight of war. Wearing those real dog tags, the genuine article, “seemed like a handshake,” Alda says. Until recently, he knew nothing about the two men whose names are on those dog tags – one, a Black soldier from the South; the other, a Jewish man from New York.

“Yet every day for 11 years, putting them on over my head and wearing them, I had a very close connection with them,” Alda says. “I always wondered what their lives were like. Were they alive, or were they dead? How had they served? They were real people to me, even though I didn’t know anything about them other than their names. But to this day, I remember the names very well, and that’s why it meant a lot to me.”

M*A*S*H GOES TO AUCTION: HAWKEYE’S COMBAT BOOTS AND DOG TAGS BENEFITTING THE ALAN ALDA CENTER FOR COMMUNICATING SCIENCE SIGNATURE® AUCTION 7353

July 28, 2023

Online: HA.com/7353

INQUIRIES

Robert Wilonsky

214.409.1887

RobertW@HA.com

These pieces of wardrobe, the last remnants of his tour of duty, mean so much to Alda he now parts with the boots and dog tags only to help fund what has become his greatest passion: the Alan Alda Center for Communicating Science at Stony Brook University.

Heritage Auctions is proud to offer Alda’s sole remaining M*A*S*H mementos in a single-lot auction on July 28. All the money raised from M*A*S*H Goes to Auction: Hawkeye’s Combat Boots and Dog Tags Benefitting The Alan Alda Center for Communicating Science Signature® Auction will go to the 14-year-old center founded by Alda, Stony Brook and the university’s School of Communication and Journalism. Heritage will also donate all of its proceeds to the center.

“Hawkeye’s boots and dog tags are not only entertainment memorabilia from a beloved series, but the cherished keepsakes of a national treasure,” says Heritage’s Chief Strategy Officer Joshua Benesh. “And before that, they were the personal artifacts of real soldiers. They now take on a new life as a source of fundraising for a noble cause in which a noble man has invested so much of his time and resources, and we are honored to be even a small part of such a grand gesture.”

They were going to do more good than sitting in my closet. They were screaming, ‘Let me out!’ I thought, what a great chance to put these boots and dog tags to work again.”

–Alan Alda

Alda helped found the center after 12 years spent hosting PBS’ Scientific American Frontiers, during which he became “a kind of pop-culture science teacher,” as The New Yorker’s Michael Schulman wrote last year. Alda began hosting the series in 1993 believing he knew enough to keep pace with the scientists he was interviewing.

But in some of the early interviews, he says now, both he and the scientists were a little uncomfortable because he wasn’t making true contact with them. It was as if he had forgotten what he had learned as an actor, and especially as an improviser, about listening and relating to the other person.

“So I began doing the interviews as if they were improvisations – listening more closely and reacting in the moment,” Alda says. “My curiosity about them was more genuine, and not just a cue for them to expound. The conversations would go in directions that neither of us anticipated.”

He saw that the scientists were becoming more alive and spontaneous. That experience sparked in Alda the idea that scientists could more clearly and vividly communicate with audiences if they had experience in combining the skills of improvisation with good message design.

Alda brought improvisational exercises to classrooms at Stony Brook and to institutions around the world. As a result, the center has trained more than 20,000 scientists in nine countries, as well as Harvard and Cornell universities, the National Institutes of Health, the Environmental Protection Agency and even the U.S. Department of Defense.

Enlarge

That experience also led Alda to host the popular podcast Clear+Vivid with Alan Alda, where he interviews scientists, authors, doctors, musicians, actors – anyone who interests him and has something substantive to say. He and Swamp-mate Mike Farrell, who played Capt. B.J. Hunnicutt on M*A*S*H, even performed a “scene” from the series written by a chatbot. Listening to the podcast is like huddling with an old friend who wants to know everything about everything. The show’s revenue also goes to the Alan Alda Center for Communicating Science.

Clear+Vivid feels like the inevitable next step in a career that has spanned Broadway, television, big-screen stints as actor and writer and director, a trilogy of celebrated memoirs and decades spent using his fame to advocate for women’s rights and better tomorrows for all.

“It’s connected to the idea that life is an improvisation for me,” Alda says. “I really didn’t have a plan when I started. The closest thing I had to a plan when I was a young actor was I wanted to act in plays that I admired in front of an audience that got it with other actors who I respected.”

And he stuck to that plan. This is why, to some audiences, he’s the man who almost became president on The West Wing; and, to others, he’s Alec Baldwin’s dad on 30 Rock or the senator who tried to ground Howard Hughes in The Aviator; and to others still, he’s one of the voices responsible for Free to Be … You and Me. But thanks in part to the endless availability of M*A*S*H on Hulu, Alda will always be Hawkeye.

Alda agreed to star in the series only after the show’s co-creators, Larry Gelbart and Gene Reynolds, vowed it wouldn’t be just another show that used war as a punchline to silly stories. Over the series’ celebrated run, Alda garnered five Emmy Awards and six Golden Globes and became its most prominent voice – as writer, director and creative consultant – and its most famous face.

“Casting Alda as the ensemble’s moral center and chaos agent was key,” critic James Poniewozik wrote in The New York Times last year, upon M*A*S*H’s 50thanniversary. By the time the series ended, with a two-hour finale watched by 106 million viewers, M*A*S*H had evolved into “a romp in the midst of a war zone [that] goes, bit by bit, deeper into night and the heart of darkness,” Poniewozik wrote. Alda co-wrote and directed its farewell.

The cast held a press conference during those final days of filming, and in photos taken that day, you can clearly see the dog tags Alda received during those first days on set. And now, with the help of the National Archives and other historical records, we know more about the men who wore them.

One of the service members was relatively easy to find: Hersie Davenport was a native of Mississippi who was 34 years old when he enlisted on July 14, 1942. Army records show he was living in Jackson, Missouri; separated from his wife, with whom he had an unknown number of children; and working as a porter when he traveled to Chicago to join the Army. Davenport, a Private First Class, served as an engineer and was discharged on December 15, 1945. Records show he died on April 24, 1970, less than three months after director Robert Altman’s adaptation of Richard Hooker’s 1968 novel MASH: A Novel About Three Army Doctors premiered in theaters. Records show Davenport is buried at the Mountain View Cemetery in Oakland.

Morris D. Levine’s name was misspelled on his dog tags, with a superfluous “s,” and his service records were destroyed in the July 1972 fire that consumed millions of military personnel files housed at the National Archives and Records Administration in St. Louis. The scant information that survives shows Levine was born on August 8, 1907, and that he enlisted in the Army when he was 35, serving as a corporal until his honorable discharge three years later on November 15, 1945. Levine died on June 9, 1973, and is buried in the Long Island National Cemetery, not far from where Alda lives today.

Alda did not know either man’s story until he decided it was time to part with the boots and dog tags, which he had kept for years in a closet because he did not know where else to store them.

“Then I realized that they could come to life again to be used to help the Center for Communicating Science because, probably, somebody would be interested in having a memento of the show,” he says. “I can’t think of a better use for them.”

He is asked: Will it be difficult to say goodbye to these last keepsakes from M*A*S*H? No, he responds. Not at all.

“Because I knew they were going to a good cause,” Alda says. “They were going to do more good than sitting in my closet. They were screaming, ‘Let me out!’ I thought, what a great chance to put these boots and dog tags to work again. For 11 years, they helped promote the idea that human connection could be a palliative for war. And now they can promote the idea that a human connection can get us to understand the things that affect our lives so deeply.”

ROBERT WILONSKY is a staff writer at Intelligent Collector.

ROBERT WILONSKY is a staff writer at Intelligent Collector.