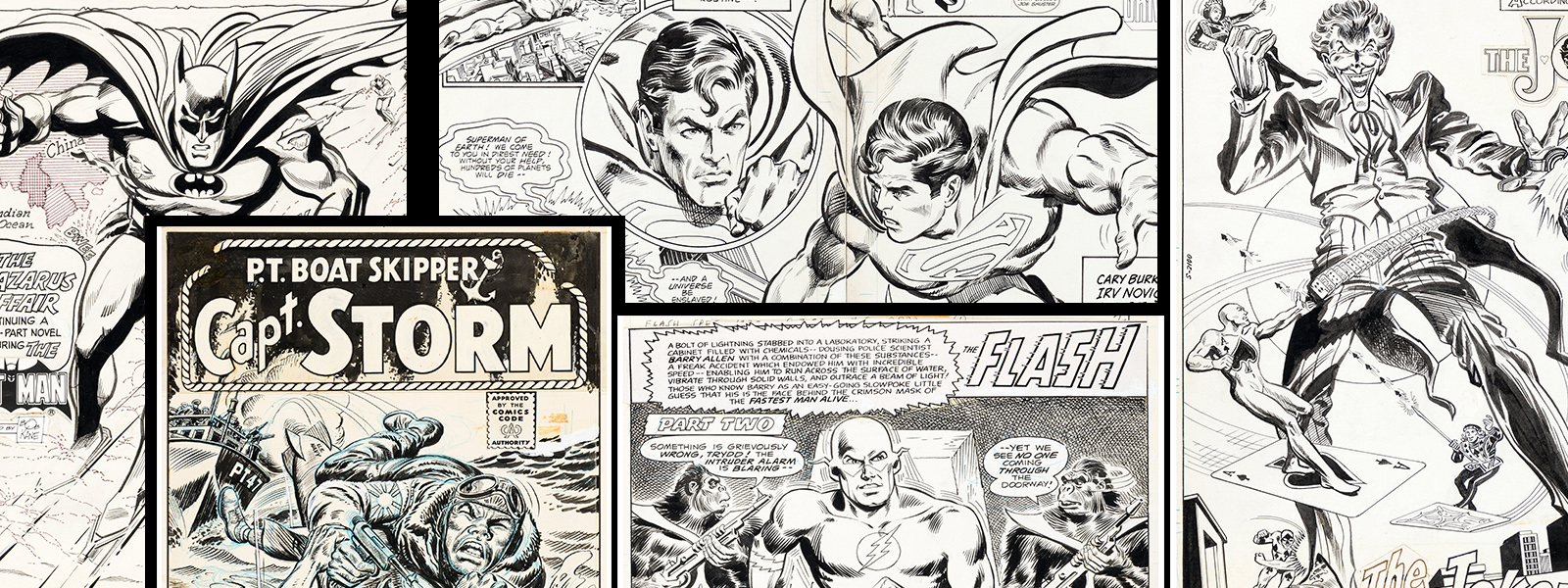

HE CO-CREATED THE SHIELD IN 1940, MADE ART THAT INSPIRED ROY LICHTENSTEIN IN THE ’60S AND BROUGHT THE FLASH, BATMAN TO LIFE IN THE ’70S

By Robert Wilonsky

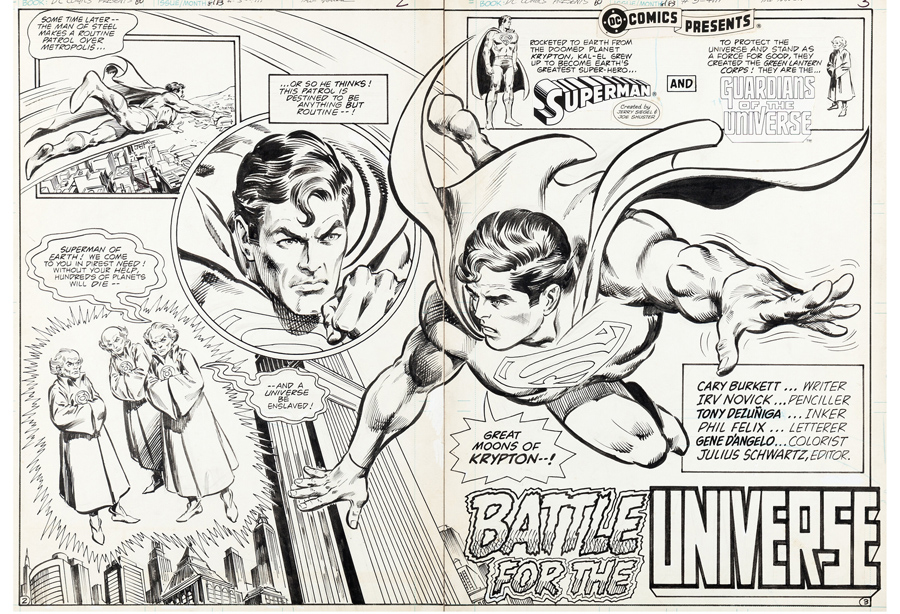

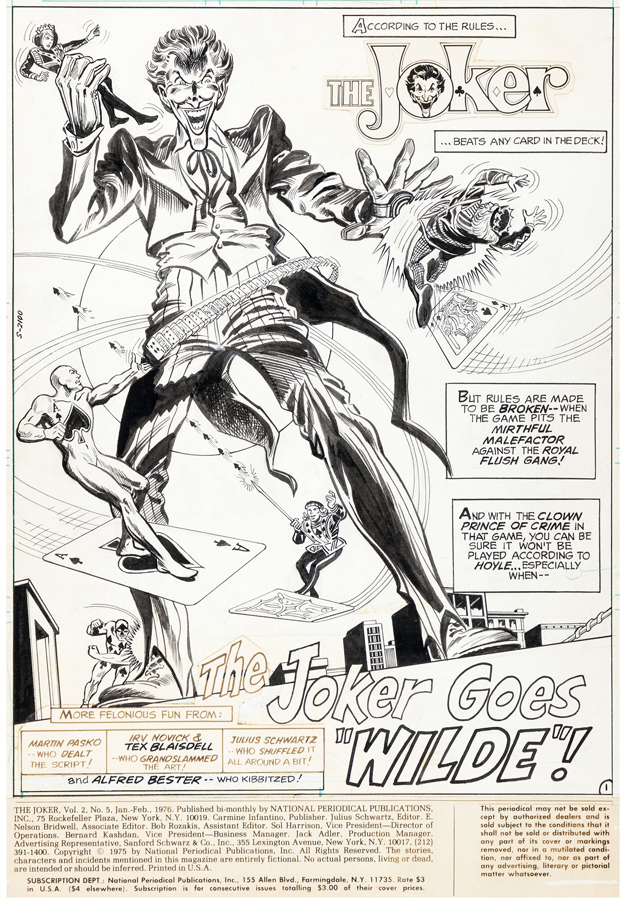

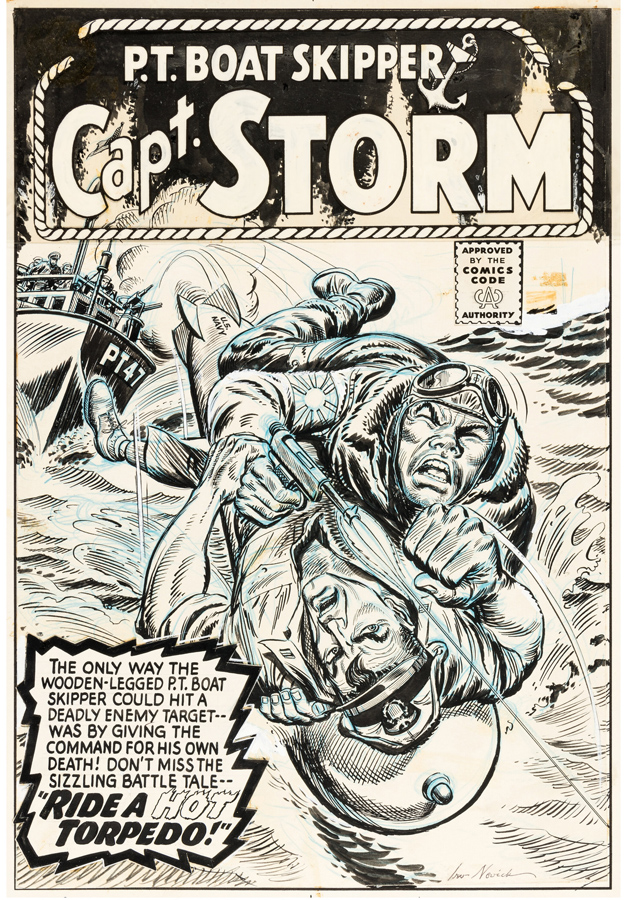

Irving Novick spent more than 50 years drawing comic books – first at Archie Comics’ predecessor MLJ, where, in 1939, he co-created comicdom’s first star-spangled hero, The Shield; then at DC Comics, where he worked his way through the battlefields of fightin’-forces comics to reach the superheroes on the other side. By the 1970s – when longhaired comics fans had grown up to become the industry’s storytellers and a generation of kids were giddily dropping quarters on his Batman and Flash books – the man called Irv stood alongside Neal Adams, Jim Aparo, Carmine Infantino and other beloved titans who defined, and delighted, the decade.

Novick was born in New York City in 1916, studied at the National Academy of Design there, counted among his influences Rembrandt and Van Gogh, and considered becoming a doctor. But beginning in 1939, he assembled a storied career that spanned more than five decades – comics’ Golden, Silver and Bronze Ages. He saw his work appropriated by pop artist Roy Lichtenstein, whose revered 1963 WHAAM! lifts wholesale Novick’s rendering of an aerial dogfight from an issue of All-American Men of War published one year earlier. And in 1975, he and writer Denny O’Neil launched the recently resurrected The Joker, which marked the first time a villain starred in his own book.

Yet Novick’s name likely registers only among the scholars and the fetishists, those who study back issues like holy scripture and pore over credits like Talmudic scholars. That is just how Novick wanted it: He didn’t attend his first comic book convention until he touched down in San Diego in 1995, long after he retired, and would later tell comics historian John Coates he was “surprised at the amount of people and industry professionals who told me they were inspired by my work.”

COMICS & COMIC ART SIGNATURE® AUCTION 7341

September 14-17, 2023

Online: HA.com/7341

INQUIRIES

Todd Hignite

214.409.1790

ToddH@HA.com

Upon Novick’s death in 2004 at 88, comics writer Mark Evanier noted that the artist “claimed to remember very little of his career and to have absolutely no fondness for any job or character over any other.” According to Evanier and everything else ever written about or said by Novick, a job was a job was a job – no assignment more special or significant than the other, and none of it worth talking about, at least in public.

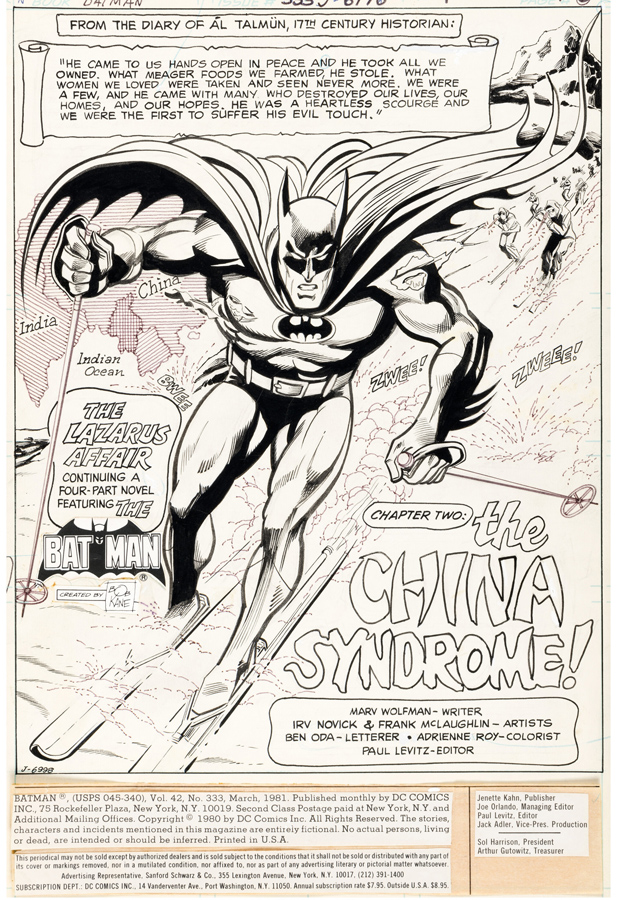

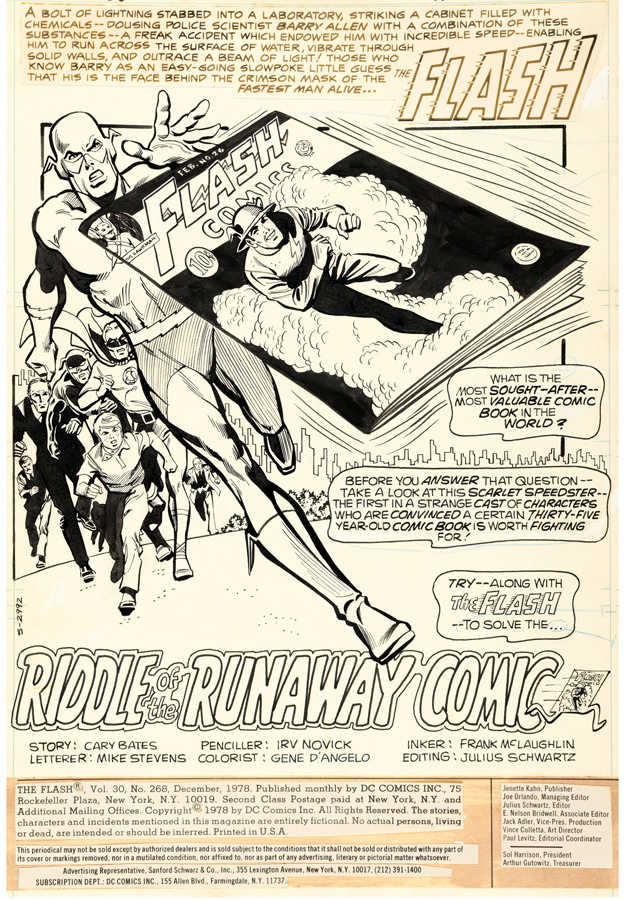

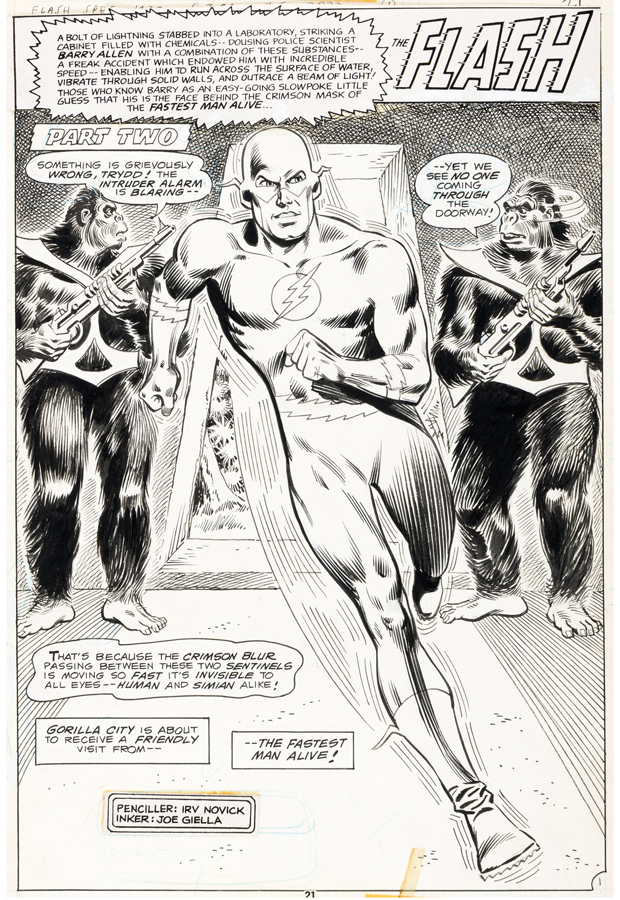

History has proved him wrong, as evidenced by the brand-new issue of Alter Ego magazine devoted entirely to the “great” Irv Novick. His mastery is evident, as well, in the 13 works of original art in Heritage’s September 14-17 Comics & Comic Art Signature® Auction, all from his time at DC.

These pages are filled with iconic images of Batman, Flash, the Joker, Catwoman and Robin and even the Shadow from his guest turn in 1983’s Batman No. 253. There are also two complete stories, including “Catwoman’s Circus Caper,” which appeared in the 100-pager Batman No. 256 in 1974. From four years later comes the entire 17-page story “Riddle of the Runaway Comic” that appeared in Flash No. 268 – one of the most memorable and meta comics stories of the 1970s, as it’s basically about how Barry Allen collects comic books featuring his Earth-2 counterpart, except Flash Comics No. 26, around which this fun tale revolves. There’s a heist, too, involving villains dressed as the Golden Age Wildcat and Green Lantern.

“Irv Novick had one of the most solid careers in comics, very much like the scenes he carved into Strathmore paper with a dark and definitive pencil line,” former DC Publisher Paul Levitz writes in the new Alter Ego. “There wasn’t anything sketchy or tentative about Irv’s artwork; he took you into a place and made it concrete and real, filled with genuine people.”

Even, or perhaps especially, if they wore colorful costumes.

“But he was very humble,” says Novick’s daughter and eldest child, Leslie Novick Frank. “Very, very humble. Even when kids came over – our friends who knew what he did for a living – he would change the conversation and engage them in something else when they asked about comic books.”

Novick’s obituary said only that he was a “Legendary Golden Age Cartoonist, co-creator of The Shield, 1st patriotic comic hero, and celebrated artist for DC Comics & Boy’s Life.”

Novick’s four children with his wife of 64 years, Sylvia, had some idea of what their father did for a living: “We knew he was an artist and that he drew comics,” Leslie says. But the kids had to sneak to read them – save for the occasional romance comic Leslie saw other girls thumbing through at summer camp. The house was filled instead with respectable magazines: The New Yorker, National Geographic, Life. There weren’t copies of All-American Men of War or Batman or The Black Hood lying around the living room. Irv taught his kids how to fix and build things.

The closest Leslie got to the world of comics was when she’d have to take the subway into Manhattan to deliver pages to DC’s legendary editor Julius “Julie” Schwartz or Carmine Infantino.

“And they would always ask, ‘Where’s your father?’ and I would always tell them, ‘He’s working on his next story.’” She laughs. “But I knew all those guys, and they were nice to me.”

Perhaps that’s because some of the artists at DC owed their jobs to Novick, who might have been humble about his talent but was also that rare creative type willing to promote the gifts of others. Myriad artists, among them Green Arrow and Superboy and Legion of Super-Heroes’ Mike Grell, often shared the same tale: They would spend years showing their work to comics and newspaper editors. Then, one day, they’d meet Novick, usually in the DC offices. And he would send them to Schwartz with the instructions: “Tell them Irv sent you.”

Comics creators adored Novick, not merely because he helped so many break into the industry he essentially helped create in the 1930s. Writer Bob Kanigher, another Golden Age great who ushered DC into the Silver Age, told The Comics Journal in 1983 that his pal Irv was “a very special case, a rare talent … Like a Brando or a De Niro who can’t give a bad performance, Irv is incapable of drawing a bad line.”

Novick was among the rare artists who wound up keeping a large portion of his work, which he gifted over the years to his kids – who, as adults, fell in love with the work to which they paid little attention as kids.

“His work is very strong, very powerful,” Leslie says. “It’s also sparse. It doesn’t have a lot of clutter. You get the message, too, right away. You don’t need a lot of panels to get that message. When I looked through the pages, I was so intrigued by how much work he was able to get out, the quality of the work and how beautiful it was. I don’t think I’d ever looked at it in those terms. I was just so impressed.”

Ultimately, Irv and Sylvia’s kids decided to save a few of their favorite pieces. But to keep it all, they felt, would be unfair to the fans who told Irv, over and over and over, how much they adored his work. For the first time, Novick’s pages come to auction. And the reason, says Leslie, is simple:

“His work stands the test of time. It’s not fussy. It’s powerful. And it’s fun, too – he had a great sense of humor. And in the end, I just hope this work gets in the hands of people who will appreciate it – who will get joy out of it.”

ROBERT WILONSKY is a staff writer at Intelligent Collector.

ROBERT WILONSKY is a staff writer at Intelligent Collector.