LEGENDS OF SPORT, MUSIC, MOVIES AND MORE LIVE FOREVER IN THE INDELIBLE IMAGES THAT MAKE UP THIS ON-THE-RISE COLLECTING CATEGORY

By Christopher Belport

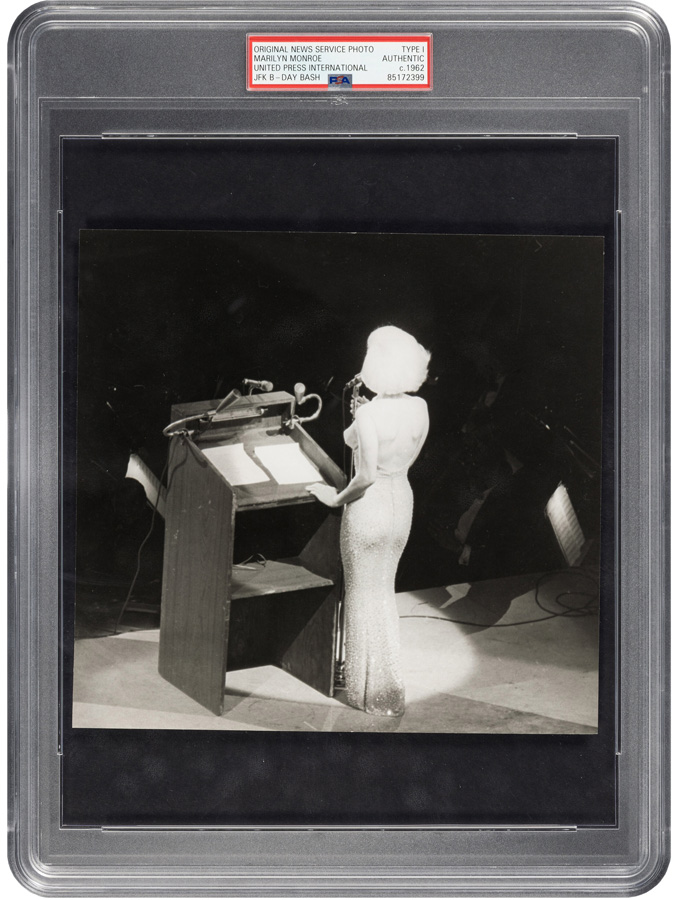

Marilyn Monroe singing ‘Happy Birthday, Mr. President’ to John F. Kennedy on May 19, 1962, at Madison Square Garden original UPI press photograph by Bill Ray. PSA/DNA Type 1. Available in Heritage’s April 7 Photo Legends Type 1 Showcase Auction.

In each genre of collecting, there exist elusive treasures of ultimate value, items that, in practical terms, are unfindable, known only in a few surviving examples, or scarce in the original state of the issue. In the art market, these would be described as blue-chip, impervious to the shocks of history, appreciable over time and of impregnable value. Type 1 photographs – which represent high watermarks of cultural life, pivotal historical events, defining achievements in sports and entertainment, and celebrity images that transcend the moment – have become among the most coveted collectibles in recent years, as desired as any Ansel Adams landscape of the American West, Dorothea Lange Depression-era portrait or Annie Leibovitz celebrity session. These iconic images, developed from the original negative during the period when the photo was taken, are as close as you can get to a you-are-there moment without a time machine.

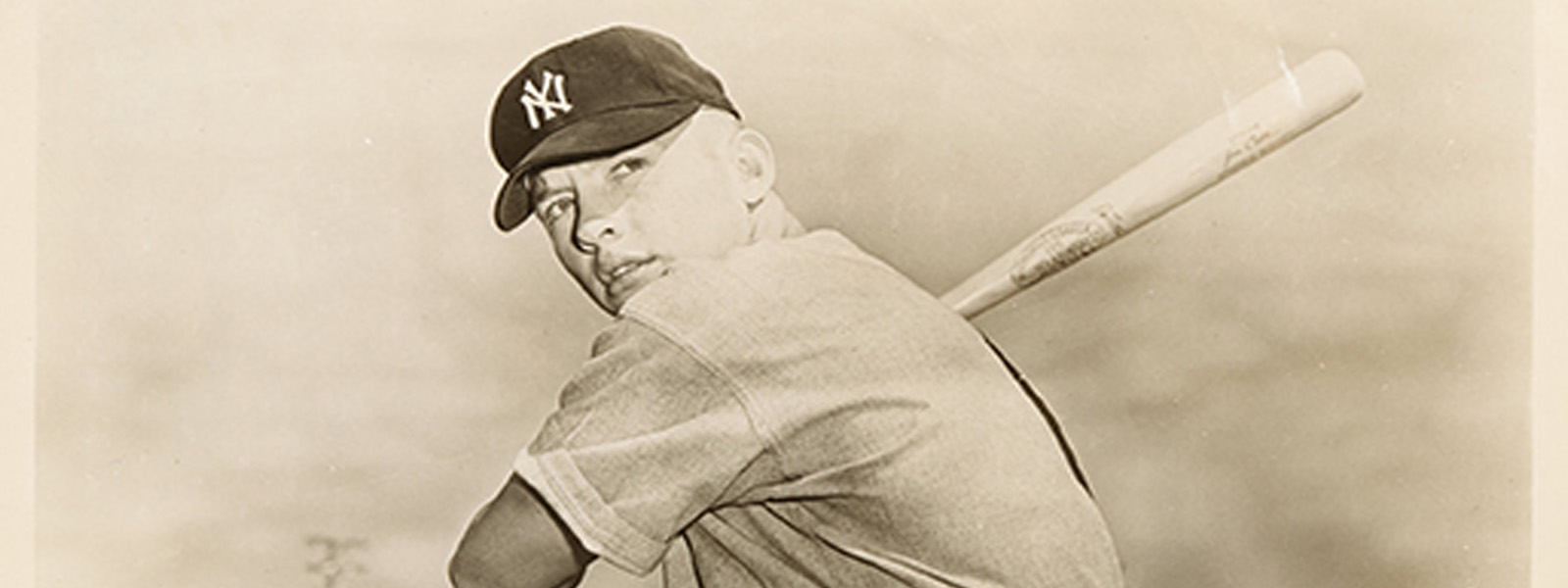

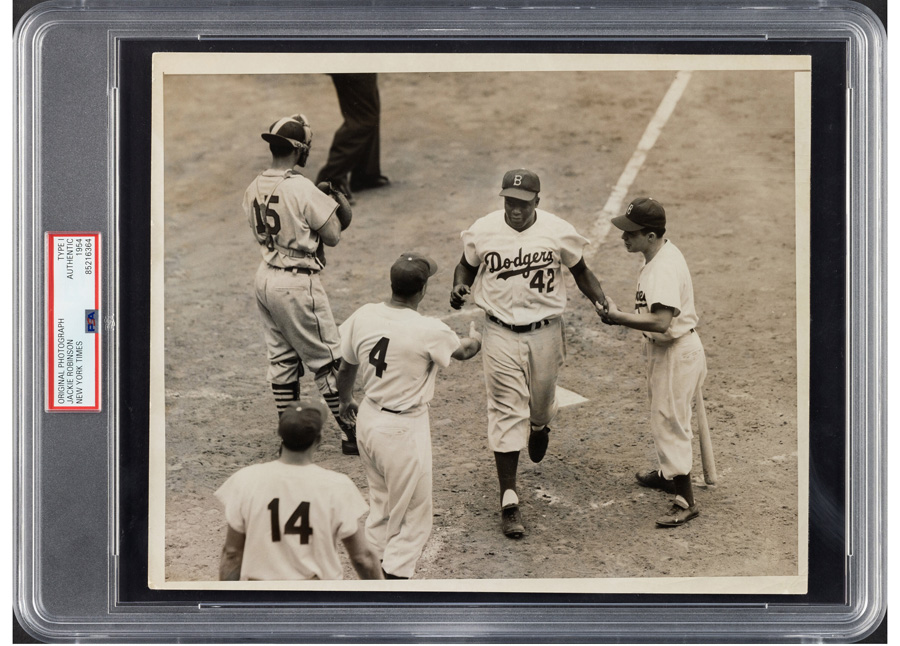

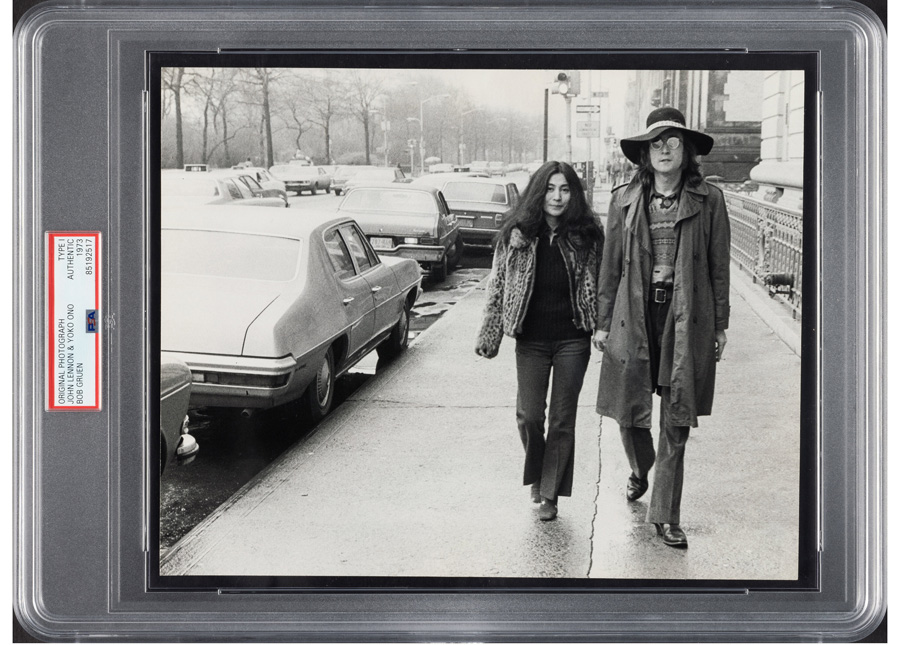

The D-Day landing, “Into the Jaws of Death” by Robert Sargent (1944), “Raising the Flag on Iwo Jima” by Joe Rosenthal (1945), “V-J Day at Times Square” by Alfred Eisenstaedt (1945), the Hindenburg disaster (1937), Guerrillero Heroico by Alberto Korda (1960), “Self-Immolation of Thích Guảng Dức” by Malcolm Browne (1963), “Man on the Moon” (1969), “Kent State” by John Paul Filo (1970), Bela Lugosi as Dracula, Boris Karloff as “The Monster” in The Bride of Frankenstein, Fay Wray in fright mode in King Kong, early baseball heroes Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig during the magical summer of 1927, Jackie Robinson and Mickey Mantle in their rookie seasons, “Black Power Salute in the 1968 Mexico Olympics” by John Dominis (1968), “John Lennon and Yoko Ono in New York City” by Bob Gruen (1973), Marilyn Monroe singing “Happy Birthday, Mr. President” to John F. Kennedy (1962): These are peaks in the history of image making, embedded into the collective memory.

‘New York Times’ press photograph of Jackie Robinson reaching home plate on June 26, 1954, Brooklyn Dodgers vs. St. Louis Cardinals. PSA/DNA Type 1. Available in Heritage’s May 5 PSA Type 1 Photographs Showcase Auction.

Type 1 photographs, as classified by Professional Sports Authenticator (PSA), represent the highest standard of value because they are printed directly from the camera negative at the time the negative was produced, within approximately two years. An original press photograph that bears the credit stamp, paper caption or date stamp intended for immediate release is a nearly exact contemporary of the depicted event, a time capsule of history in visual terms. The image may have a prolonged life reproduced in magazines, newspapers and other media, but the first editorial use of the image, often the full uncropped version of the exposure, will forever remain definitive.

John Lennon and Yoko Ono in New York City, 1973, original press photograph by Bob Gruen. PSA/DNA Type 1. Available in Heritage’s April 7 Photo Legends Type 1 Showcase Auction.

After successive uses, the negative accrues dust, scratches or smudges, and later prints may show wear that cannot be reversed in the pre-digital age of the traditionally made print. Many original press prints bear editorial annotations in grease pen, produced to indicate to the photo editor where to crop or resize from the original exposure. Some prints show retouching in graphite to add contrast, add or reduce depth, or highlight a contour or an outline. These markings, seen most universally in fashion magazines but also portrait subjects or public events of notable subjects to eliminate trivial detail from the background, add layers of historical value since they reveal the editorial underpinnings of the first version of the image shown to the world.

‘The Bride of Frankenstein’ (Universal, 1935) Boris Karloff as The Monster studio release photograph by Roman Freulich. PSA/DNA Type 1. Available in Heritage’s April 7 Photo Legends Type 1 Showcase Auction.

Movie photographs printed in the portrait gallery in special double-weight papers or by the unit still photographers for publicity vary greatly from print to print. The earliest prints benefit from the pristine negative, and the select attention of the gallery specialist developing by hand in reduced numbers before the negative is transferred to the publicity department for mass printing.

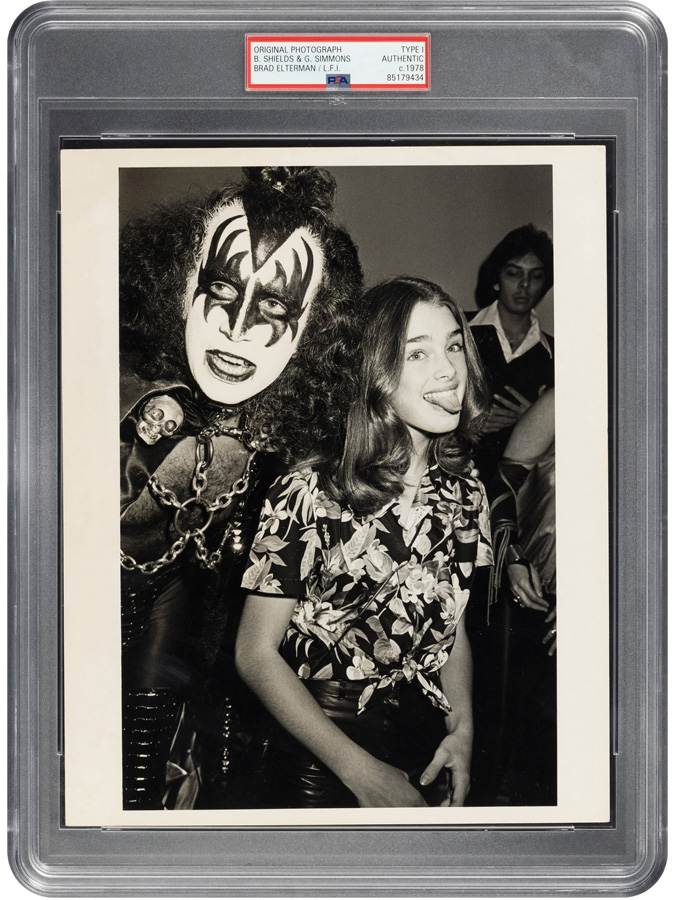

Brooke Shields and Gene Simmons of KISS at a party for Blondie at Fiorucci in Beverly Hills on December 12, 1978, original press photograph by Brad Elterman. PSA/DNA Type 1. Available in Heritage’s April 7 Photo Legends Type 1 Showcase Auction.

The celebrity photographer Ron Galella, famed for his obsessive pursuit of Jacqueline Onassis, is known primarily for secondary images reproduced in the National Enquirer and not the double-weight prints he produced in his darkroom with full credit provenance on the verso. Celebrity or paparazzi photographs are often overlooked in the record of public sales of fine photographs. Still, the lasting imprint produced by small cameras at public events, on the fly or in protected intimate spaces is of indelible images that define the zeitgeist for all time. Who can see “On Albert Einstein’s 72nd Birthday” (1951) by Arthur Sasse without invoking “Brooke Shields and Gene Simmons of KISS at a Party for Blondie at Fiorucci, Beverly Hills” (1978)?

Type 2 photographs are produced from the camera negative shortly after the original use, or about two years or more. Many working photographers print from their negatives later in their careers, using high-contrast papers to a standard unavailable when the original work print was made. There was no photography market in the modern sense until after 1970. Photographers who worked for commercial media and provided work prints to their editors had little need to make multiple prints. It became necessary later in their careers for established photographers to print in a fixed or open edition from their camera negative to sell commercially.

This is a finite exception to the rule that only Type 1 prints are the exemplar in photographic terms. However, to identify the first-made print as the standard of value, the market value of the original print must supersede the photographic benefits of some later prints because of historical claims as an object of scarcity.

Type 3 photographs may be printed from a duplicate negative or an internegative, an enlargement negative derived from the camera negative, and used for wide reproduction or advertising. Many photographs made after 1960 were printed from a black-and-white 8-by-10-inch enlargement internegative derived from the color 2.25 camera transparency or 35mm color negative, especially since color prints were expensive to produce in quantity.

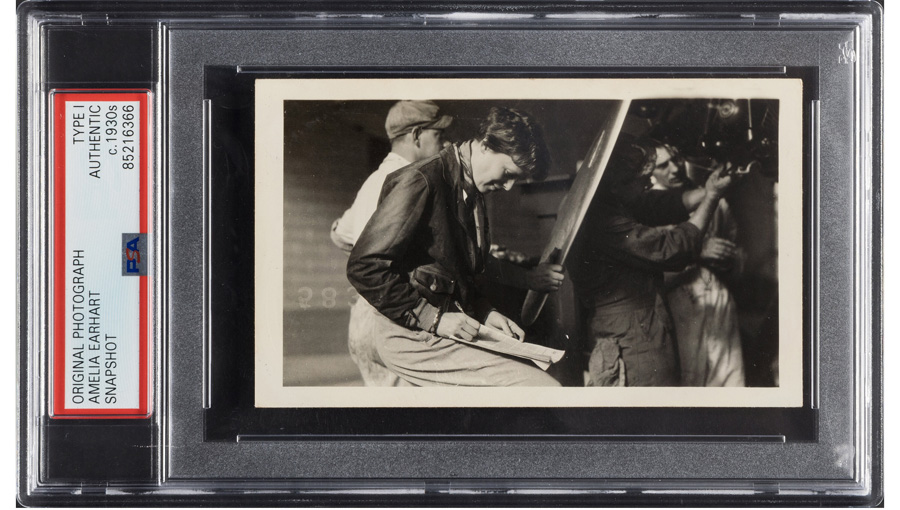

Amelia Earhart in a flight jacket original photograph, circa 1930s. PSA/DNA Type 1. Available in Heritage’s May 5 PSA Type 1 Photographs Showcase Auction.

There is also the medium format photograph or Polaroid color print that belies the common assumption that size confers value. Looking at this small photograph of Amelia Earhart in her flight jacket by an unknown photographer, the depth of focus and framing as a studied landscape would be framed, is extraordinary. The aura is one of soulful mystery, beguiling and painterly in the balance of delicate light effects, like brushwork applied on a canvas. Read from left to right as twin composition panels, with the left, of Earhart, human-scaled with the sunlit warmth tilting on her face to create a profile etched in relief, and the right, framing the pair of airplane mechanics, is concentrated and hushed in tilted shadow as a masterful chiaroscuro. Additionally, there’s the ideal patina of 1930s gelatin silver in the mid-tones, as time has added warmth and presence.

Then there is the Polaroid or small color photograph that came into wide amateur use after 1960, most often unique as a print and as a historical document, date-stamped, and unlike Kodachrome film, which suffers from color shift to magenta, remains bright with consistent colors and is elusive as a feather circling in an updraft.

April 7, 2024

Online: HA.com/66151

INQUIRIES

Joe Maddalena

214.409.1511

JMaddalena@HA.com

In many cases, Type 1 photographs were the works of photojournalists who turned into inadvertent artists while capturing the famous in off-guard moments. They were images used in newspapers and magazines and meant to be disposable. But yesterday’s news has become today’s stuff of legend. That’s why these photos are so sought-after among collectors, historians and fans – and why Heritage recently announced that it will hold Type 1 photographs auctions every six weeks for the foreseeable future, beginning with its April 7 Photo Legends Type 1 Showcase Auction. As a result, collectors will have countless opportunities in the coming months and years to own the history-makers while they were making that history.

CHRISTOPHER BELPORT is Consignment Specialist in Entertainment at Heritage Auctions.

CHRISTOPHER BELPORT is Consignment Specialist in Entertainment at Heritage Auctions.