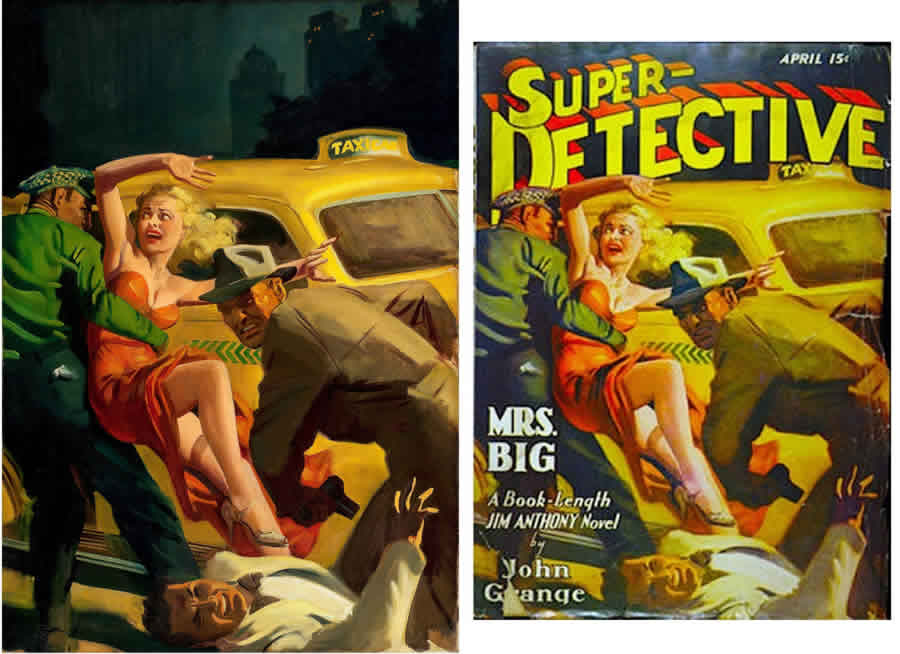

PULP MAGAZINES DELIVERED FAST OPENINGS, SMACKED READERS AND, ULTIMATELY, FOUND A PLACE IN POP CULTURE

By Douglas Ellis

Only one pulp genre featured an editor who would go on to win the Nobel Prize in literature, would print the first magazine stories of an author who would go on to win the Pulitzer Prize, and included a title which was a favorite of rough riding Teddy Roosevelt.

Excerpted from The Art of the Pulps: An Illustrated History (IDW Publishing, $49.99 hardcover, release date Sept. 26, 2017), by Douglas Ellis, Ed Hulse and Robert Weinberg. ©2017 Elephant Book Company Ltd. Reprinted with permission.

That genre was adventure and, fittingly, the pulp that pulled off this trifecta was Adventure, referred to by Time as “The No. 1 Pulp.” In its early days, Sinclair Lewis, who would win the Nobel Prize in 1930, was employed by the magazine as an associate editor. T.S. Stribling, whose magazine fiction career was launched with the appearance of “The Green Splotches” in the Jan. 3, 1920, issue of Adventure, won the Pulitzer Prize in 1933. And as reported in Time, the former president had been “one of its most ardent readers.”

The adventure pulps were the natural outgrowth of the general fiction pulps that began the pulp era. As specialization took hold of the field, pulps such as Argosy, Adventure, The Popular, Top-Notch, The Blue Book Magazine, and Short Stories resisted the trend and continued to publish a mix of various types of adventure fiction. Archibald Bittner, editor of Argosy, who had also been an editor at Adventure and Short Stories, wrote in 1930 that, “We can use almost any type of adventure, and about the only thing we bar is the domestic, sex, or morbid themes. Argosy is a man’s magazine, but we use some stories with a strong romantic interest. We use foreign adventure with preferably an American hero, Northern stories, sea stories, war stories, railroad stories, circus stories, sport stories of all kinds, including racing, boxing, baseball; mystery stories … and even westerns when we can find one which is different.” That description could have fit many of the adventure pulps.

Enlarge

Measured by number of issues, it was the most popular of the pulp genres. Roughly 140 different adventure titles surfaced over the 60-plus years of the pulp era, fewer than the detective genre and comparable to westerns. However, several of the top adventure titles lasted for over 25 years, and many were published multiple times a month at various times throughout that span. Just focusing on the “big six” titles already mentioned, Argosy published over 1,500 issues over 47 years, Adventure over 750 issues over 43 years, The Blue Book Magazine over 550 issues over 46 years, Short Stories over 850 issues over 44 years, The Popular Magazine over 600 issues over 28 years, and Top-Notch over 450 issues over 27 years. While other genres could lay claim to a title or two that could rival these numbers, none had nearly as many.

TO ATTRACT AND hold the reading public, the top adventure pulps strove for authenticity. As veteran pulp author E. Hoffman Price described it, “The purpose of the adventure story is to convey dramatically the glamour of far-off places and people; to give retired adventurers a re-creation of familiar scenes, and to afford escape for the rocking chair adventurer. This requires authenticity.” Some pulp authors, such as Captain A.E. Dingle, Bill Adams, and S.B.H. Hurst, acquired their knowledge first hand; in their cases, by sailing the globe for years and visiting scores of exotic ports. Others, including Farnham Bishop and Arthur Gilchrist Brodeur, meticulously researched the backgrounds of their stories, to lend them verisimilitude. This was also true of authors like Henry Kuttner, a regular in the pages of the pulps who once advised authors looking to crack the adventure pulp market, “Research will cover a multitude of sins.”

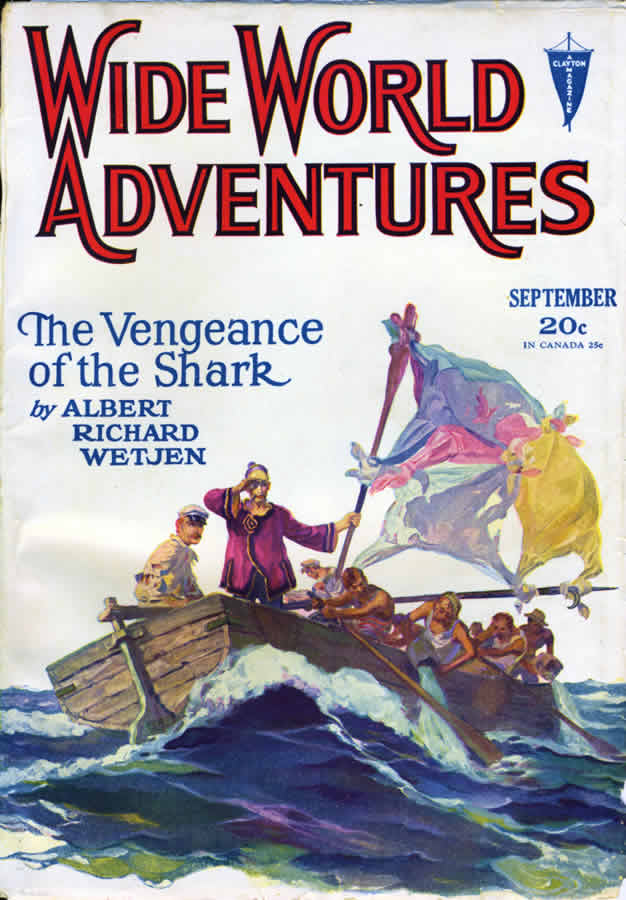

Nearly every pulp publisher that published more than a few titles put out an adventure pulp, and many published several. Fiction House’s first pulp, Action Stories, was an early entry into the adventure field. Thrilling Adventures was the flagship adventure title of Ned Pines’ Thrilling group. Popular Publications had several at different times, including Dynamic Adventures, Dime Adventure, and All Aces, culminating in their purchases of Adventure in 1934 and Argosy in 1942. The Clayton chain hit the newsstands with The Danger Trail, which morphed into Adventure Trails and then into Wide World Adventures, as well as Complete Adventure Novelettes, Jungle Stories, Soldiers of Fortune, and others. Columbia countered with Adventure Novels and Short Stories, Adventure Yarns, and more, while Red Circle kept readers entertained with Adventure Trails (not related to the earlier Clayton title) and Complete Adventure Magazine. The Ace group, which was apparently fond of numbers, sent 10 Action Adventures, 10 Short Novels, and 12 Adventure Stories into the fray. MacFadden tempted the adventure public with Red Blooded Stories, Tales of Danger and Daring, and one of the longest titles of the pulp era, Fighting Romances From the West and East (as with many other pulps, the term “romance” being used to denote adventure rather than love). The Munsey and Street & Smith houses each published roughly a dozen adventure pulp titles over time.

Enlarge

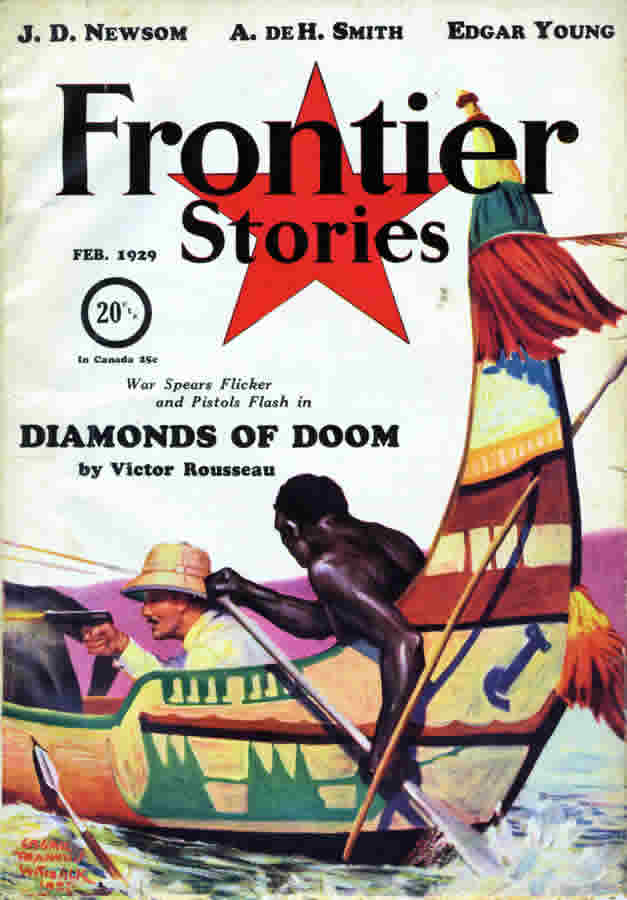

Adventure pulp stories could be set anywhere, and as the pulp field embraced specialization, pulps devoted to particular types of adventure stories eventually sprang up. Golden Fleece, Cavalier Classics, and Soldiers of Fortune focused on historical adventure; Far East Adventure Stories and Oriental Stories dealt with the mysteries of the Far East; Sea Stories, South Sea Stories, and High-Seas Adventures explored adventures on the waves; Foreign Legion Adventures dealt with the rough and ready men of the French Foreign Legion; and Jungle Stories, Thrills of the Jungle, and Tropical Adventures took their readers deep into the humid heart of the darkest jungles. Yet some adventure pulps had even more “exotic” backdrops, such as Fame and Fortune, which dealt with adventures set in the financial markets, and Newspaper Adventure Stories, which was set in the dog-eat-dog world of journalism. Adventure, apparently, was where you could find it.

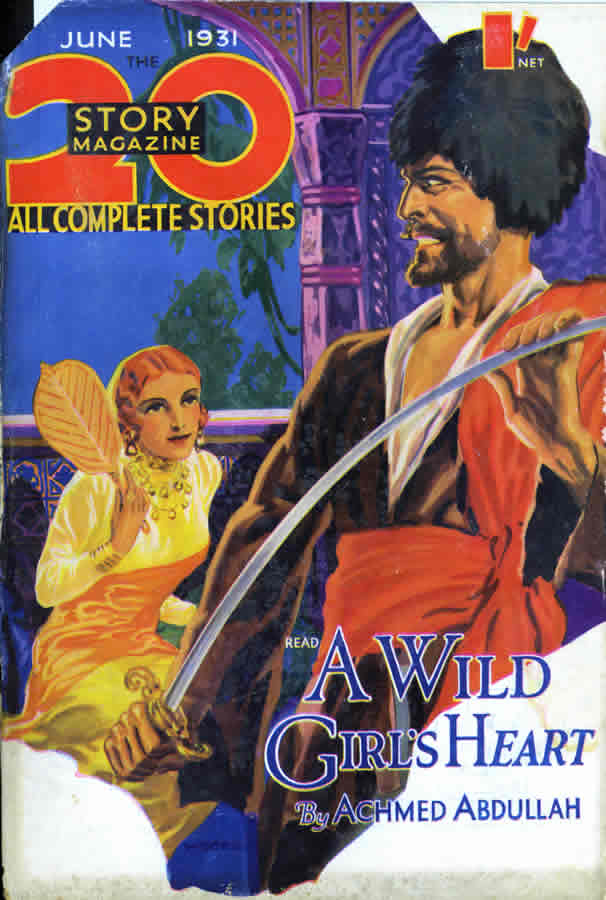

BUT WHILE THE stories could be set anywhere, with very few exceptions the hero of these tales, no matter the setting, was always a white man—usually an American, but often British or sometimes Canadian. As V. Edward Sutherland described the prototypical adventure pulp hero for readers of Writer’s Digest who were looking to crack that market, “The red-blooded, swashbuckling type. Always a he-man. There are substitutes for most everything nowadays, but there just doesn’t seem to be a substitute for this kind of hero.”

Enlarge

A quick glance at some of the popular recurring characters who appeared in Argosy or Adventure bears this out. Edgar Rice Burroughs’ Tarzan, though he was raised in the jungle by apes, was a British peer by birth, if not by upbringing. Max Brand’s brilliant Doctor Kildare was an American medical doctor, while C.S. Forester’s Captain Horatio Hornblower was a British naval hero fighting the French during the Napoleonic Wars. In the realm of historical fiction, there could be a bit of latitude in nationality, as demonstrated by Johnston McCulley’s swashbuckling rebel, Zorro, born in Californio (not California), and Talbot Mundy’s wily Tros of Samothrace, a Greek rebelling against Roman rule in the time of Julius Caesar. Mundy’s other chief series character, James Schuyler Grim – better known as Jimgrim – was an American who’d been employed by the British secret service. Each knew what to do when the chips were down, and allowed their enthusiastic public to live vicariously through them. And in many cases, their popularity transcended the pulps and transferred to other mediums, especially the silver screen, as pulp stories were a fertile field for the early days of motion pictures.

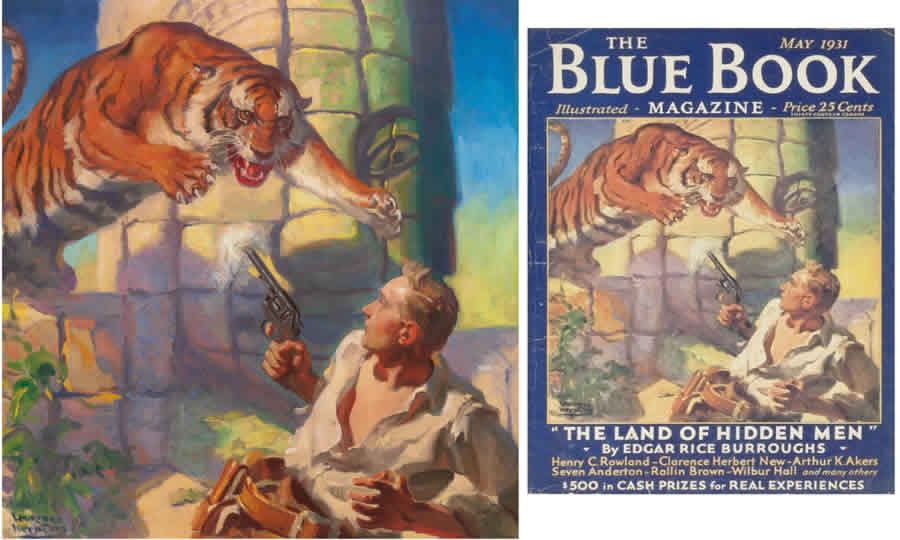

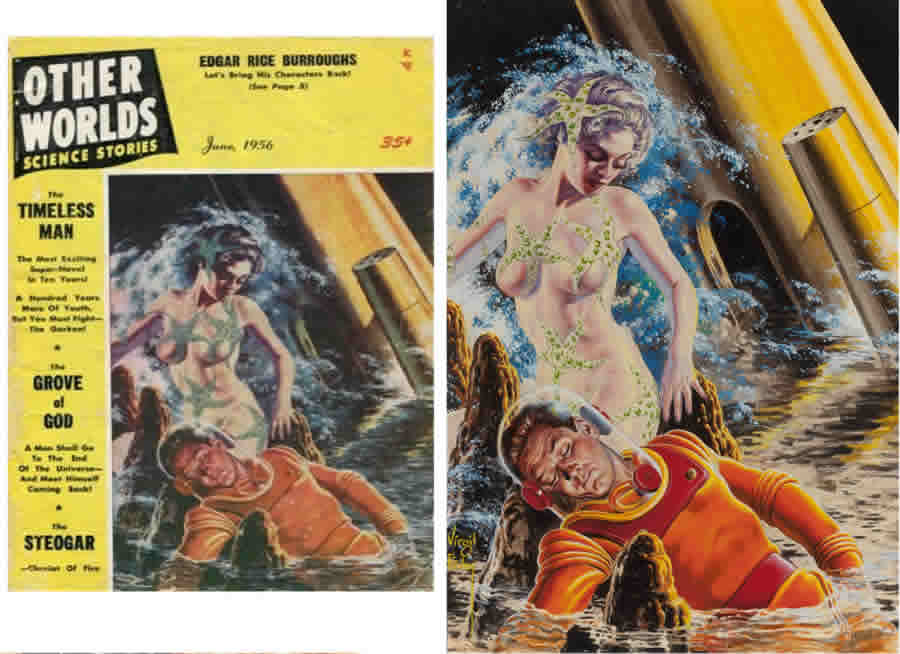

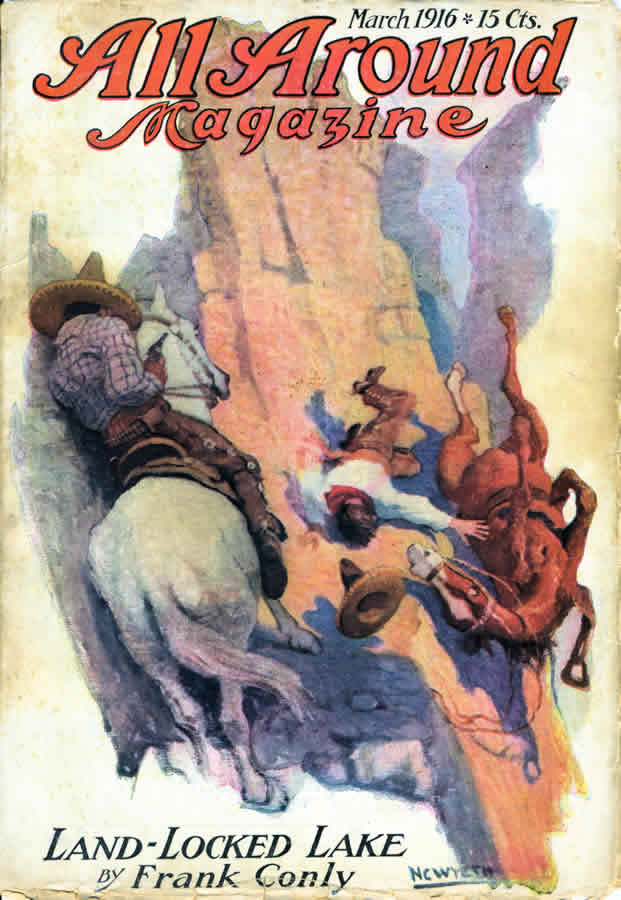

Enlarge

To depict these heroes and their adventures on the covers and interior pages of the pulps, a host of artists were kept busy. Several chains had favorite artists, although they were rarely exclusive arrangements. For Munsey, these included P.J. Monahan, Paul Stahr, Robert Graef, Marshall Frantz, Emmett Watson, and Virgil E. Pyles for covers, and Samuel Cahan for interiors. Over at the Clayton chain, Stephen Waite, Joseph Doolin, and Elliott Dold were kept busy painting, while prolific black and white artist John Fleming Gould got his start working on their pulps. Both Columbia and Red Circle employed John Walter Scott on many of their titles, while A. Leslie Ross was another Columbia mainstay. Laurence Herndon was The Blue Book Magazine’s primary cover artist for over a decade.

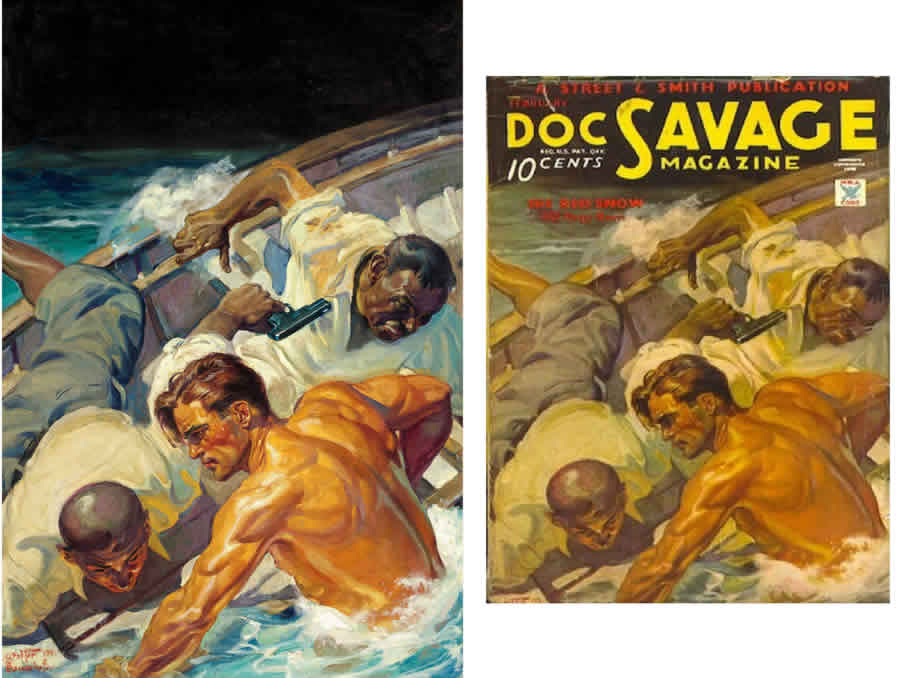

MOST ARTISTS, HOWEVER, worked for several publishers across the adventure pulp field. Among the most prolific was Walter Baumhofer, known as the King of the Pulps; while best remembered for his Doc Savage covers, he contributed both covers and interiors to pulps such as The Danger Trail (which published his first pulp cover) and Adventure. J. Allen St. John, Hubert Rogers, and Hans Wessolowski (known as Wesso) may be most associated with the science fiction pulps, but they also contributed several adventure pulp covers and illustrations. Working across genres was the norm for pulp artists.

Several would go on to fame for their post-pulp work. These included Nick Eggenhofer, Gerard Delano, and Tom Lovell, each of whom found fame in the fine western art market, but also contributed both cover and interior art to the adventure pulps.

Inside their rough pulp pages, writers were ready to smack the reader with a fast opening, but their vivid covers were what caused the reader to pick up the magazine in the first place.

©2017 Elephant Book Company Ltd. Reprinted with permission.

Enlarge

Enlarge

Enlarge

Enlarge