AS HE PREPARES TO PART WITH NEARLY 300 PIECES FROM HIS DECADES-IN-THE-MAKING ASSEMBLAGE, THE LEGENDARY PUBLISHER REFLECTS ON HIS COLLECTING JOURNEY

By Denis Kitchen

Editor’s note: Denis Kitchen was an original member of the Underground Comix movement in the late 1960s and ’70s, as well as the founder of the pioneering publishing house Kitchen Sink Press. A portion of his collection will be offered in Heritage’s April 4-7 Comics & Comic Art Signature® Auction.

My collecting bug developed very early. As a child of the 1950s – straddling the pre- and post-Code era – I would excitedly peruse the nearest drugstore spinner racks for new comic books, determined to spend my 50 cent weekly allowance on the five most exciting choices. It wasn’t easy: Uncle $crooge, Little Lulu, Batman and Superman vied with creepy horror and crime titles to capture my attention and dimes.

I tended to buy superhero and adventure comics, not because they were necessarily favorites, but because I quickly learned those issues had heightened value on the secondary market, i.e., swapping with neighborhood kids. Local boys would typically trade two – or even three – humor comics to get a desired superhero, and I gladly took them up on it, growing my early collection disproportionate to a limited budget. I also sought older pre-Code comics from the 1940s that chums sometimes inherited from older brothers. The age itself wasn’t the point: Older comics, at 52 pages, provided a bigger bang than thinner modern ones.

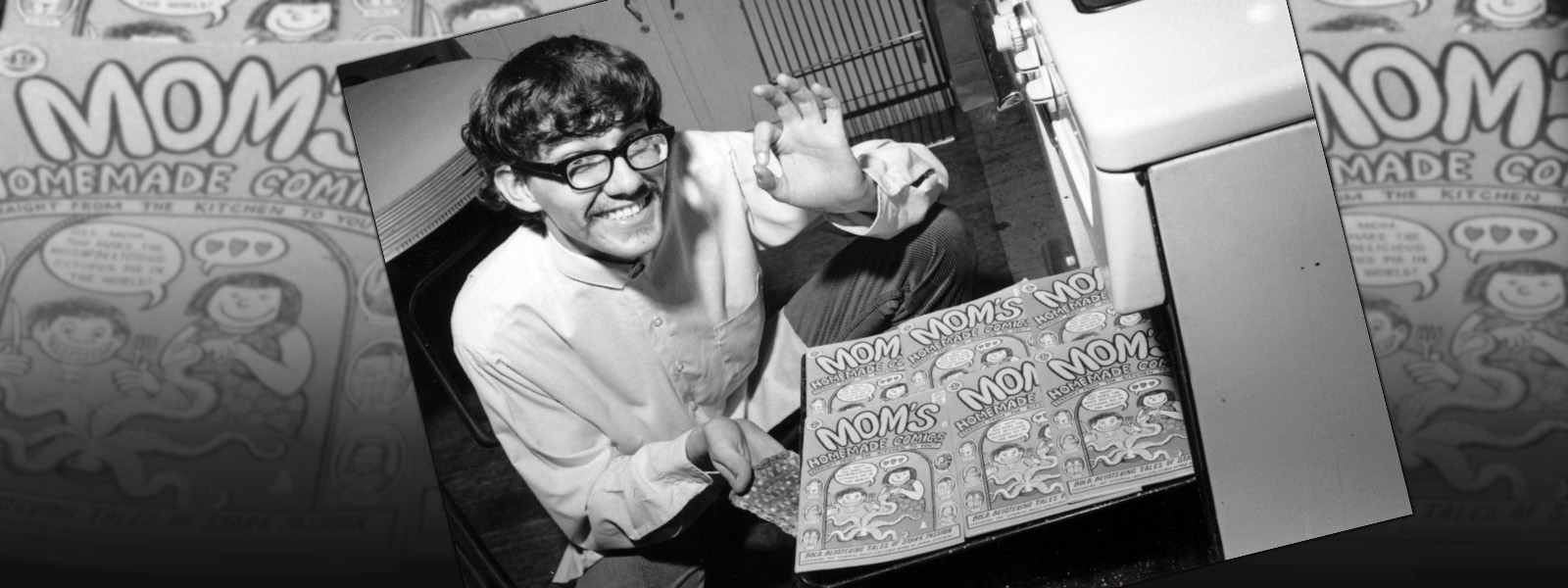

The Kitchen Sink Press team in 1981

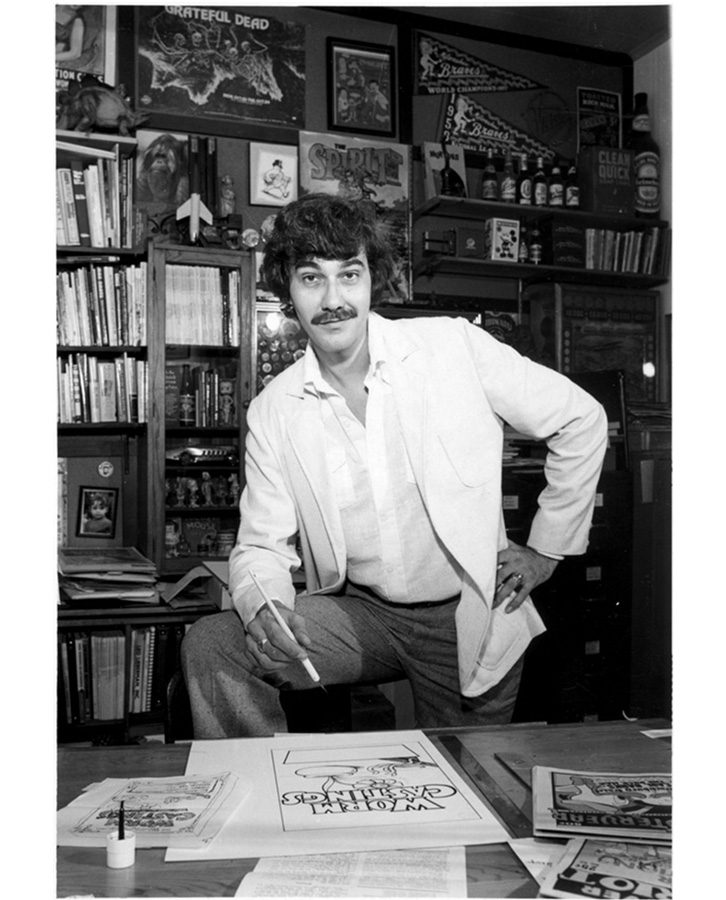

Kitchen photographed in 1980 at his Kitchen Sink Press office, then in Princeton, Wisconsin

As I steadily accumulated comics, I realized that some, especially if left on the couch or floor, would suddenly disappear. Every young person of the era knew: Mothers cared not a whit for comics and readily tossed them like yesterday’s newspapers. I confronted my otherwise wonderful mother about the untenable situation. Appreciating my passion, she wisely advised that if I kept my comics “neatly arranged” in my bedroom, she would not trash them. Suddenly I was a serious collector with very neat stacks and, soon, studious recorded inventories.

A summer job when I was approaching 16 in 1962 significantly boosted my budget and coincided with Stan Lee’s fresh take on superheroes, which rekindled my interest in the genre. By the time I was 18 and beginning college I was hooked on Marvel and for two or three years did something rather remarkable in hindsight. I instinctively knew the exciting issues of Fantastic Four, Spider-Man, et al. were truly special, so I made regular trips to an East Side Milwaukee drugstore and bought five copies of every Marvel I liked. Four of each title were set aside, pristine mint, while the fifth remained accessible and well read. Around the time I graduated and needed to focus on career and survival, I stopped actively collecting comic books but retained what I had.

THE DENIS KITCHEN COLLECTION COMICS & COMIC ART SIGNATURE® AUCTION 7369

April 4-7, 2024

Online: HA.com/7369

INQUIRIES

Todd Hignite

214.409.1790

ToddH@HA.com

The many hundreds of untouched early ’60s Marvels were stashed away for two decades until my growing but cash-strapped publishing company, Kitchen Sink Press, then in rural central Wisconsin, needed working capital. Not surprisingly, my small-town bank viewed lending money to hippie enterprises with considerable suspicion. So, to raise money, I took a then-current Overstreet Price Guide and the long boxes of pristine Marvels to my tables at Chicago Comic Con, where the majority quickly sold at prevailing market prices. At the time I drooled over the windfall revenue: My 10 cent or 12 cent student investments were suddenly bringing as much as $100 or even $200 a pop. Today, of course, some of those same early Marvels, mint, can bring many thousands each. But at the time, the quick cash infusion helped Kitchen Sink grow. Should I have saved one each of key issues for longer storage? I learned early on not to look back.

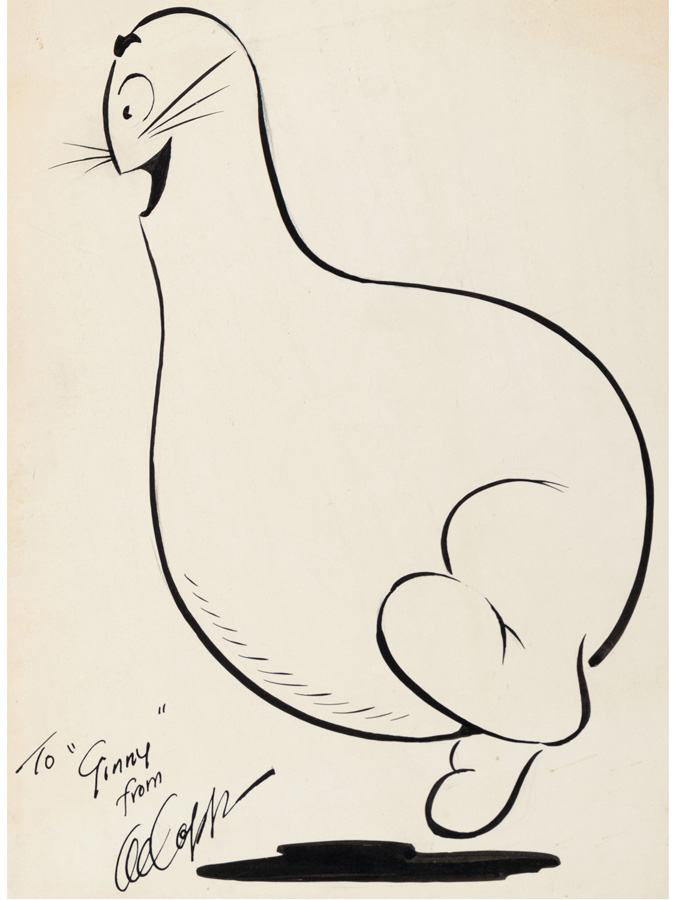

This circa 1949 image of one of Al Capp’s happy-go-lucky Shmoos is one of the many ‘Li’l Abner’ works in Kitchen’s collection.

In 1969 I encountered convention impresario (and later Direct Market founder) Phil Seuling, who asked me to create a logo and cartoon ads for him. He mentioned acquiring a stack of original Li’l Abner Sundays “for a song,” so after the first job I did for him, he said, “How much do I owe you?” As a longtime Al Capp fan, I said, “Pay me in Abner originals.” We were both happy with that fee structure. When I told Phil I was on the lookout for other vintage comic art, he referred me to an old-time collector in Brooklyn named Abe Paskow. Before long, Abe sent a tube in the mail to this total stranger in Milwaukee. Inside, carefully rolled, were two beautiful 1940s Tarzan Sundays by Burne Hogarth. His note said, “You can have one for $50 or both for $75. I was somehow able to scrape up 50 bucks (a month’s rent then), but for the life of me another $25 was out of reach, so I had to return the second Hogarth. Those were the kinds of bargains available in the prehistoric days of comic art collecting, as well as the recurring nightmares of a starving cartoonist.

As an earnest amateur I was also periodically stung. One particular incident lingers. Around 1970 I attended an estate auction in Milwaukee and picked up an early Peanuts Sunday for 20-some dollars. A steal, even then! Shortly afterward I spotted a small ad in Comics Buyer’s Guide offering Jack Davis art for sale or trade. I loved Davis art and was anxious to own a classic page. But without sufficiently establishing what I was getting in return, I foolishly mailed the Charles Schulz art for what ended up being a low-grade Davis quickie. Hard lesson learned.

My passion for comic art jumped a notch in 1971 when Seuling invited me to his big summer convention in New York City, my first. Several exhibitors had eye-popping vintage art on display. My disposable income as a struggling young cartoonist and publisher was still limited, but I bought what I could. The complete Sheena story in this auction set me back $75, no small amount then, augmented by a few newspaper dailies. But more importantly I became aware of a new, wider world of aesthetic riches and professional sources.

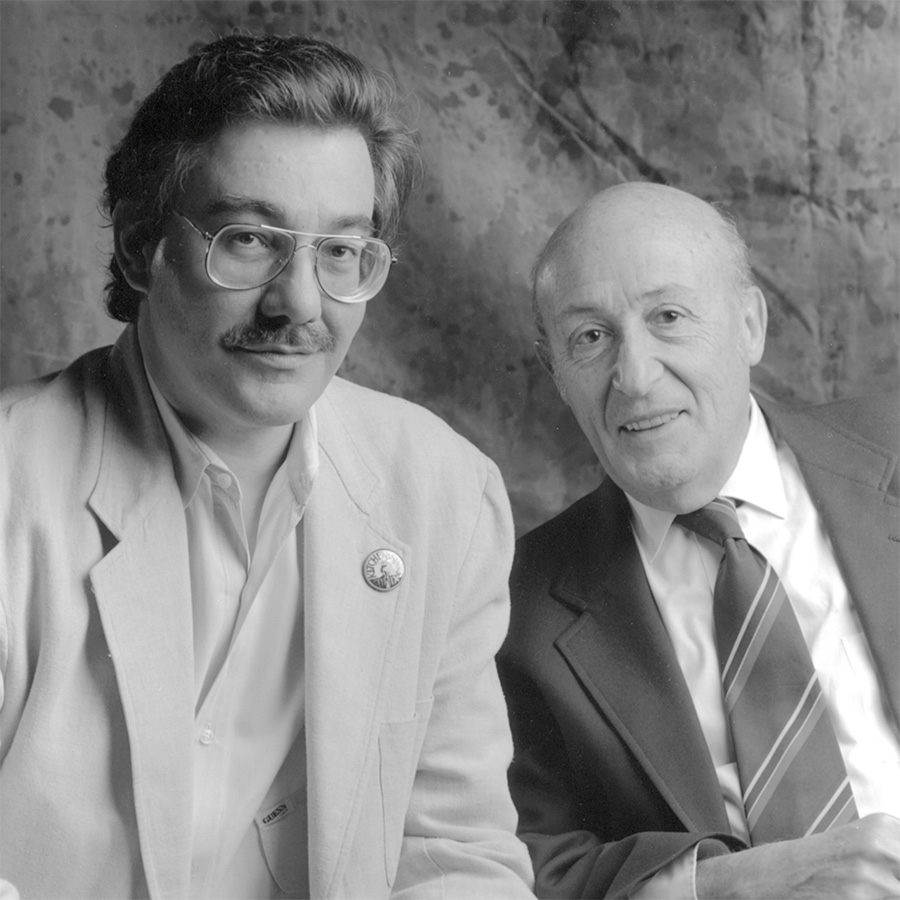

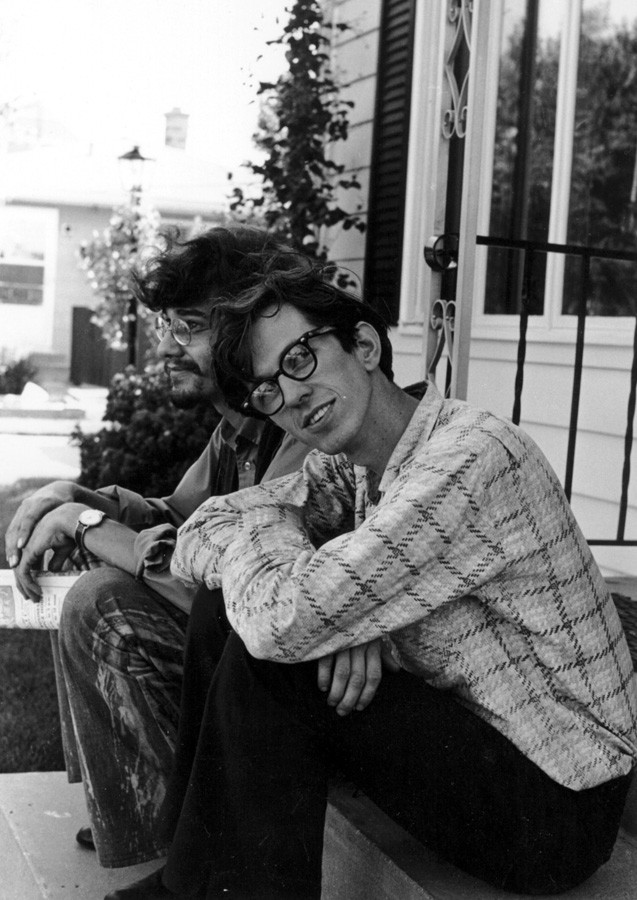

Kitchen and cartoonist Will Eisner

The 1971 convention was also where I met and began doing business with Will Eisner. He was already a legend in comics, but, despite the three-decade age difference and the stark contrast of our appearances – his balding head and suit and tie versus my long hair, beard, bell bottoms and whiff of weed – we hit it off. The following year he drew a guest cover for the third issue of my Snarf anthology. When the original arrived, I fell in love with the image of Commissioner Dolan and The Spirit entering my headquarters, located literally “underground,” in the sewers. I called Will to ask if I could acquire it, expecting an unaffordable price. Instead, he said, “How many issues of Snarf do you ordinarily sell?” “Ten thousand,” I answered. “Well,” he said, “if you can sell twenty thousand, you can keep the art.” I couldn’t believe my ears! It should go without saying that I aggressively hustled sales on that issue like no other title before and managed to reach the 20,000-copy threshold, thus securing the cover art that hung on my office wall for decades.

I realized only later that Eisner, who had taken a liking to me and my unconventional enterprise, was somewhat subtly being a business mentor – by motivating me to develop better marketing skills. But, despite that Snarf cover experience, I was still unaware of the somewhat cavalier attitude he had at the time toward his own originals, until I visited his Park Avenue office in 1974. Next to his desk that day I noticed the tight pencil of Warren’s Spirit magazine No. 7 cover sitting atop his trash bin. As we discussed business, I couldn’t take my eye off the drawing. Finally, I said, “Uh, Will … are you throwing away that Spirit drawing?” “Why?” he said. “Do you want it?” When I answered affirmatively, he retrieved the drawing and inscribed it, “To Denis Kitchen – From out of my Waste Basket – Will Eisner.” I assured him that other collectors would appreciate such discards and counseled him to hang on to similar future drawings. It proved to be a form of reverse mentoring.

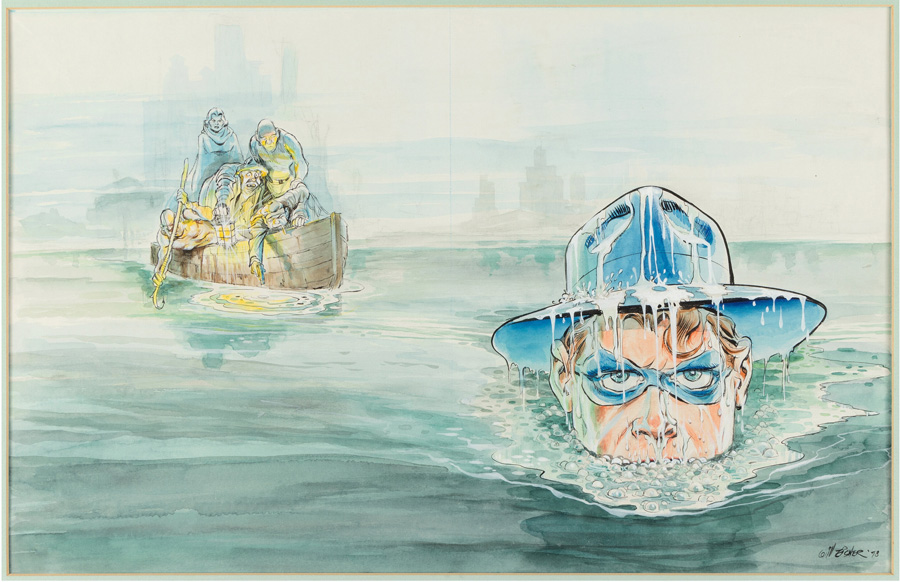

The series of full-color paintings Will Eisner created for the 1970s ‘Spirit’ magazines are among the most accomplished artworks of his career. This 1979 piece was later used as the front cover for the career-spanning retrospective ‘Will Eisner: The Centennial Celebration 1917-2007.’

Over the years Will proved very generous to me (the Spirit head-in-the-water painting in this auction was a wedding gift) and to others. But he was also a realist as interest in comic art grew, so early on he engaged comics writer/historian Catherine Yronwode as his first art agent. In the pre-digital era when I was publishing The Spirit, Will’s brother and office manager Pete would ship the originals for each upcoming magazine to Kitchen Sink, and we’d shoot the art on our large flatbed camera. The day the art for the 1947 story “Il Duce’s Locket” arrived, I was stunned by the beauty of the splash page, featuring seductive femme fatale P’Gell. I called Cat, who quoted, “The splash page is $750 or the full story $2,000.” I couldn’t manage the full story at the time but luckily acquired the splash, with never a moment of regret.

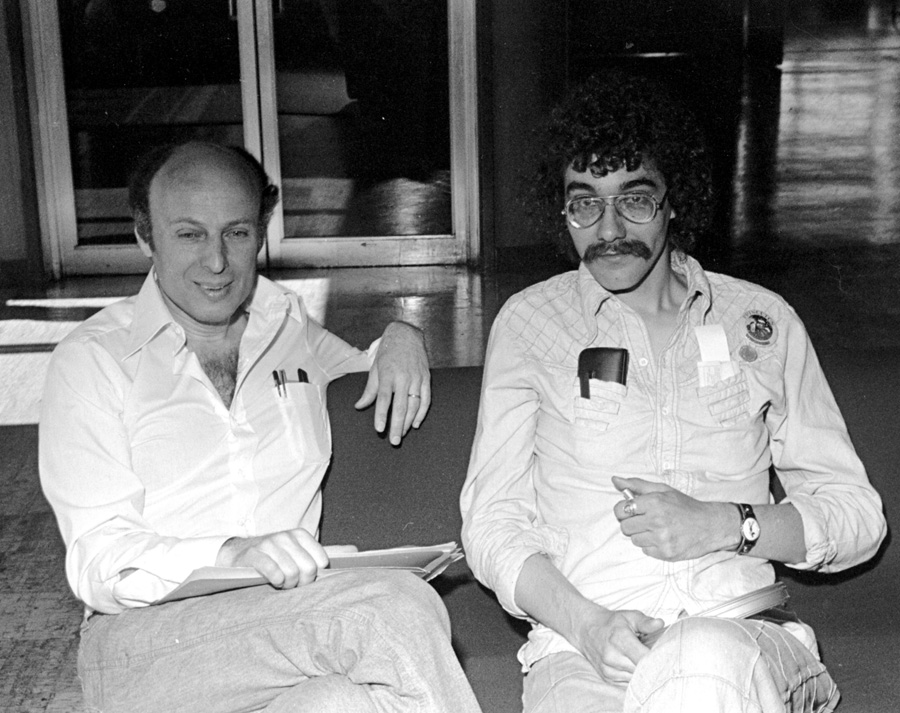

Cartoonist Harvey Kurtzman with Kitchen

Harvey Kurtzman was another comics giant I had the honor of publishing and becoming a friend of. In the early 1980s I purchased the amazing “Goodman Meets S*perm*n” spread from Will Elder and Harvey for $600, a substantial sum at the time. Later, for significantly higher amounts, I was able to acquire some other favorites, like the earliest Humbug covers in this auction. Sometimes admired art can boomerang in an unexpected fashion: I had seen and long admired Harvey’s magnificent 1954 Marley’s Ghost pages but could not afford them. When Harvey later asked me to agent some of his art, I placed those pages at Sotheby’s, where they sold. Years later, in 2007, when the original buyer placed four of the key Marley’s Ghost pages with Heritage, I was the successful auction bidder. And now they will boomerang to a lucky new collector.

While I clearly love the art of earlier generations, a disproportionate portion of my art collection, not surprisingly, consists of underground cartoonists’ art. I had the distinct advantage of being a publisher and fellow artist from the movement’s emergence in the late 1960s, with regular and direct contact with nearly all colleagues. Original comic art was priced pretty low in the early to mid-1970s, but it was lower still if drawn by grungy hippies. Often, I simply swapped my own art or merchandise for art by fellow cartoonists. Howard Cruse, for example, was a big Capp fan, so a subscription to a complete set of Li’l Abner hardcover books (27 volumes) translated to a short stack of Cruse originals. Likewise, I’d swap with Jay Lynch, Peter Poplaski, Steve Stiles, Justin Green, “Grass” Green, Richard Corben and others. No one at the time thought of future values as a factor – we simply liked each other and their respective work.

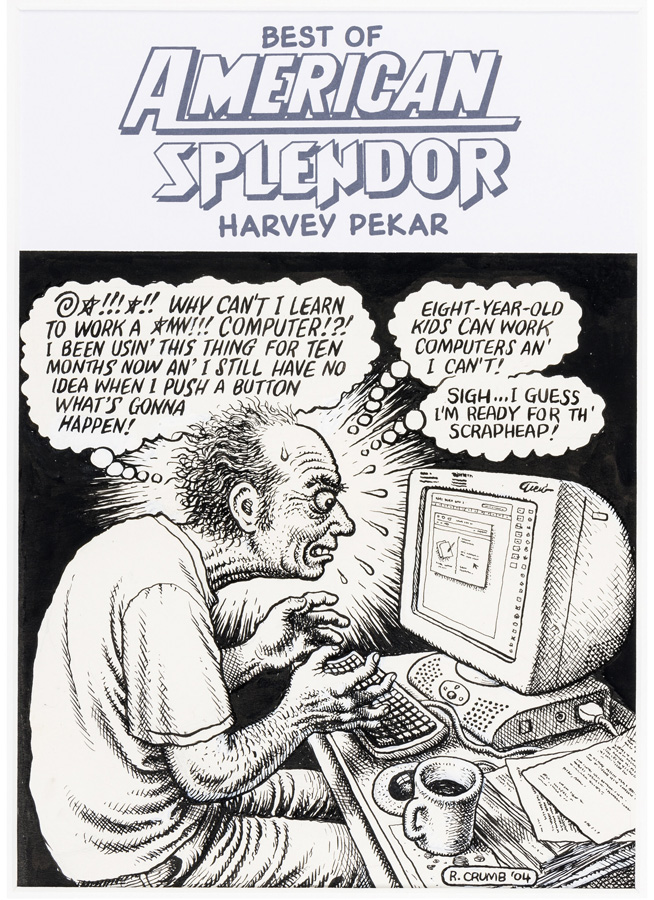

Robert Crumb completed this ‘Best of American Splendor’ cover art in 2004, the year before its publication.

Kitchen and cartoonist Robert Crumb

Robert Crumb first visited my Milwaukee apartment/office in 1970 or ’71. Swapping art for art with him was not an option – he didn’t collect art. But when he saw my 1940s Wurlitzer jukebox and the numerous 78 rpm records that supplied it, we bonded on a separate musical level. We began trading from the start: A short stack of blues records for an original by him seemed perfectly fair to both of us, even if the platters might have cost me only a few bucks, because finding scarce labels and tunes with minimal scratches can consume considerable time and energy. Nor was it always 78s that tempted Robert: In exchange for designing Kitchen Sink’s “barn” letterhead in 1985, for example, he asked for a 1929 Montgomery Ward catalog he saw on my table.

In the mid-1980s I published the then-unknown Mark Schultz, and we became good friends. When computers were still fairly new and quite expensive – around six grand in current dollars – I bought an Apple IIe. When I was ready to upgrade a while later, Mark, a frugal Dutchman, wanted his first computer and he suggested swapping some of his art for my used Apple. I agreed, thinking Mark was getting a pretty good deal at the time. As it turns out, those early Xenozoic Tales covers and drawings I received are worth a little more than that powerful 48 KB computer. Retrospection is always easy.

More often than not, I was also in a position to purchase art from colleagues. As the owner of a publishing and distribution company, with a stake in a retail head shop and mail order business, and with a 10-acre farm, I was often undercapitalized but still had more resources than most underground cartoonists. Thus, when I admired a story or a cover, I was sometimes able to provide ready cash when an artist’s landlord was knocking. At other times I would buy desirable pieces via Russ Cochran’s auctions or Illustration House or comic art dealers such as Tom Horvitz, Tony Dispoto and Rob Stolzer. And so the collection steadily grew.

Art Spiegelman’s 1974 ‘Self Portrait with Cartoon Characters’ illustration original art

Sometimes neither swapping nor cash was involved; artists would sometimes just gift art to a colleague they liked. And, on occasion, they could forget they did so. In 2009 I co-curated a major exhibition of Underground Comix art. The art publisher Harry N. Abrams produced the accompanying hardcover book, Underground Classics. The exhibit included a favorite from my collection: an Art Spiegelman parody of a 1930s Ernie Bushmiller self-portrait in which Ernie asks his characters Nancy, Sluggo and Fritzi Ritz if they have strip ideas for him. Spiegelman’s 1974 version depicted himself asking the same question of an abstract Picasso-inspired woman from his Ace Hole, Midget Detective; Ace Hole himself; a concentration camp mouse from Maus; and Nancy (to underscore that the piece was an homage).

When Spiegelman, who very rarely sells his own art, saw this image in his comp of the Abrams book he called me, somewhat indignant. “I’ve been looking for that art for years,” he said. “Where did you get it?!” “It’s very simple,” I said. “You gave it to me many years ago!” “I don’t remember that,” he responded. “I don’t remember that at all.” I detected more than a hint of suspicion in his voice. Did he think there was something unsavory in the backstory? So, I calmly explained to Artie that, in preparation for the exhibit, I had to reframe the drawing. In removing it from the cheap frame it had been in for 35 years, I was myself suddenly reminded of the unusual nature of its provenance.

In those pre-digital days, correspondence was the primary form of communication. Artie mailed a handwritten letter to me on August 1, 1974. Perhaps he couldn’t find a piece of blank paper at that moment in time. More likely, he knew how much his friend in Wisconsin loved Nancy. And so he wrote that letter on the back of the art in question. Artie absorbed the explanation. He then apologized for his tone and jokingly added, “I believe you. I can barely remember anything from the ’70s!”

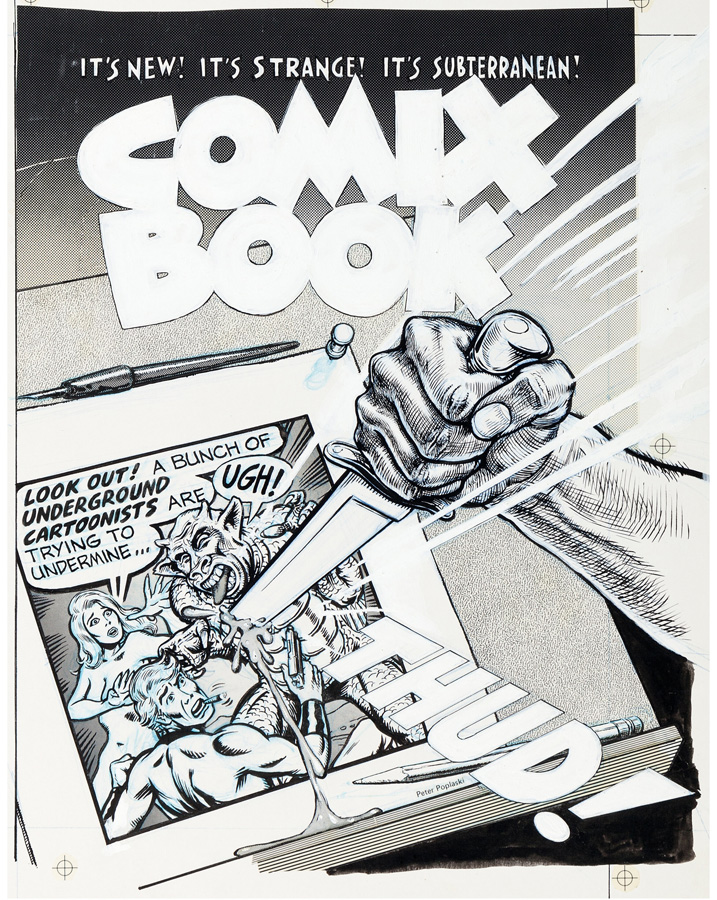

Peter Poplaski’s ‘Comix Book’ No. 1 cover original art (Marvel, 1974). The short-lived title was an attempt by Kitchen and Marvel Comics’ Stan Lee to tap into the burgeoning popularity of the Underground Comix movement.

Almost every piece in this auction has its own backstory, some more interesting than others, but time limits what can be shared here, so I’ll leave collectors and prospective bidders with these final thoughts. Over nearly six decades of collecting comic art, I never thought seriously of art as an investment: I bought or swapped for pieces and artists I admired. When I acquired work of creators I respected, even when somewhat out of fashion or derided by critics, I would derive endless pleasure from viewing the originals. Only a fraction of any collection can be hung on walls and shared easily with visitors, but even when I’d open flat files with multiple examples, I’d get continual pleasure recalling story sequences, observing the evolution of styles, or studying the often-meticulous linework or the confident snap of a sable brush. It never got old, even when I did.

Some Heritage customers skimming the auction listings might think, “This guy was once a big Marvel fan. Where are some classic pages and covers?” They aren’t here. Even as my collection grew to exceed 1,500 pieces, there was not a single Marvel or DC example. When scouring dealer tables back in the day for artists I sought, I’d continually see Marvel and DC covers at prices so cheap they’d stun contemporary collectors. While I could respect the craftsmanship of many of them, they didn’t speak to me, so I always passed. No disparagement of others’ tastes is intended; I simply grew bored with superhero comics. I personally think the market for superhero art is wildly overblown, but that’s just one man’s opinion. As this still rather esoteric collectible market matures, I predict it will be artists like Kurtzman, Eisner, Raymond, Crumb and such who will be recognized as the future Rembrandts.

From a purely transactional hindsight, of course, I could kick myself for ignoring those bargain-priced Hulk covers and Ditko Spider-Man pages. But do I regret those decisions? No. Aesthetics aside, collecting, for most with “the bug,” is an emotional process at its core. I selected affordable artwork that I truly loved, and I know most collectors understand, even if their tastes differ. Some of the pieces I acquired did accrue rapidly in value and are the highlights of this auction, while more obscure artists will appeal to fewer eyes, but both ends of that wide value spectrum gave me pleasure. Anyone who selects art primarily for its investment value is merely a speculator, not a true collector, but I repeat the truism because some collectors come to this realization slower than others.

I hope that the wide variety of items being offered here, items that I admired so dearly for so long, will find new homes and owners who share my deep passion for comics history and who can appreciate the unique aesthetic appeal each original distinctively possesses.

DENIS KITCHEN is an author, editor, literary and art agent, and curator of comic art exhibitions. He is also the founder of the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund.

DENIS KITCHEN is an author, editor, literary and art agent, and curator of comic art exhibitions. He is also the founder of the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund.