BEFORE SELLING, AUCTIONING OR DONATING YOUR FINE ART, FOLLOW THESE ESSENTIAL STEPS

By Christina Rees

There are a few reasons you may find yourself in possession of some artworks you don’t want to keep: You inherited the art from a family member or friend, you collected art in the past that you’ve since moved away from taste-wise, or you’ve decided to downsize and no longer have room for your complete collection. But disposing of fine art can feel awkward. A sculpture, a painting, a lithograph, a photograph: An artist worked hard on the piece, and at one point, some art collector (maybe even you) loved it, but that doesn’t mean you have to hang on to it forever. Here are some steps you can take when you’re staring at a stack of paintings you know you won’t be hanging in your living room anytime soon.

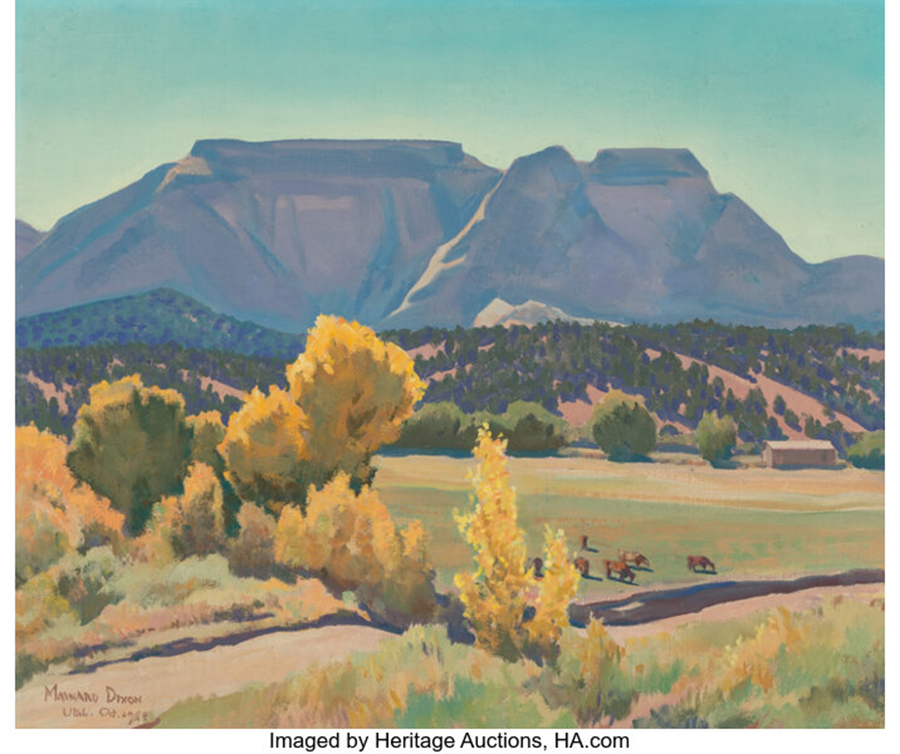

Maynard Dixon’s ‘Bright Morning, Utah,’ October 1944. Sold for $175,000 in a November 2022 Heritage auction.

Know Your Market

First, some basics about the two art markets: A fine artwork that trades hands for the first time is on the primary market; the seller sets the price or negotiates it with the buyer. “There may or may not be an established market price for that work, often based on the history and strength of the artist’s career and/or whether the artist’s work is currently trending regionally or more widely,” says Frank Hettig, Vice President of Modern & Contemporary Art at Heritage Auctions.

After the first sale, if that artwork trades hands again, it is considered a secondary market work. This is resale. This is your market. Primary market prices can be higher than secondary market prices (this is common, especially for contemporary art when the artist is not widely known), but if the artist’s work has an established market history, the secondary market price can be higher than the primary market value. Generally, an artwork doesn’t retain market value unless the artist or the work is quite established. Market value comes from a wide consensus established among dealers, collectors, collecting and exhibiting institutions like museums and nonprofit spaces, auction houses and their results, media coverage, and journalistic and academic analysis and criticism.

Many art dealers who deal privately or who run commercial art spaces (gallerists) deal in both primary and secondary markets and may well be your first point of contact in determining if the art you’d like to part with has a value that would make a business deal worthwhile. Initial conversations with art dealers and auction houses don’t cost anything but your time. If you think the artwork is something someone else would pay good money for, be prepared to make some phone calls and send some emails.

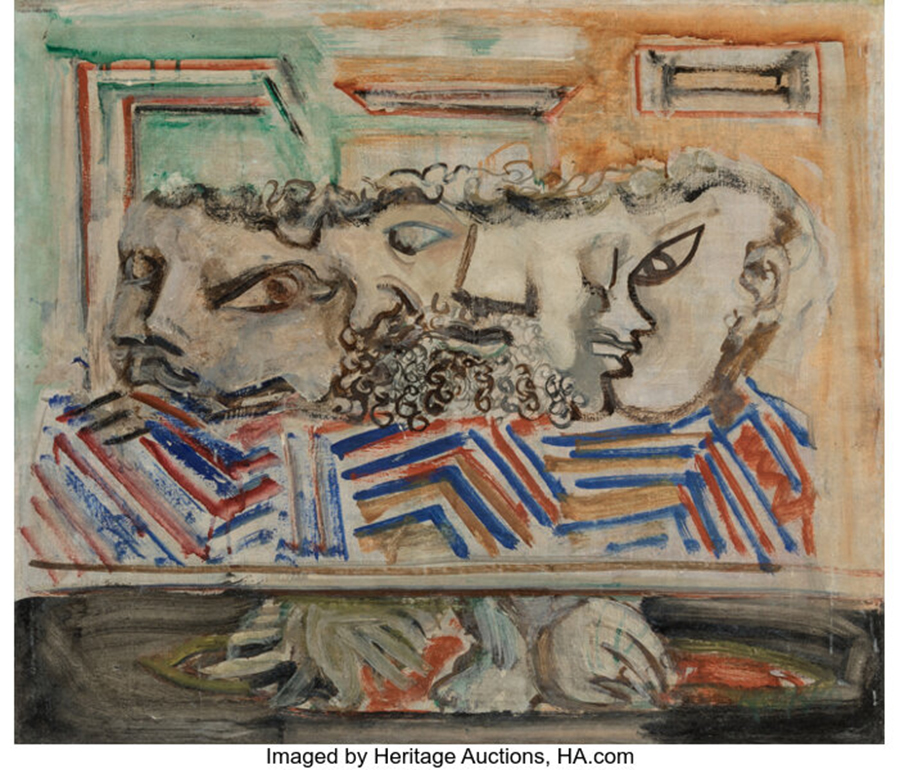

Mark Rothko’s ‘A Last Supper,’ 1941. Sold for $1,455,000 in a November 2022 Heritage auction.

Reach Out to the Original Seller

If you know where the artwork was purchased (there may be a label affixed to the work with this info) or have a purchase invoice for the work, your first step is to contact the gallerist or dealer who originally sold the work. The original dealer may be willing to simply buy back the artwork at what they deem a fair price, though this isn’t terribly common. A dealer may also offer to try to find a buyer for the work and take the work from you on consignment, which includes a written agreement: They attempt to sell the work for an agreed-upon period of time and will take a commission from the sale, often somewhere between 10 and 50 percent, depending on the value of the work and how difficult it is to sell.

You can also contact a gallerist or dealer who works with similar artworks in period and style. It may take some effort before you get traction; older artworks can feel untethered to any market if the original seller has evaporated. If the work has value, however, an art dealer with any familiarity with the genre, region and period should be able to steer you in a helpful direction: to another interested dealer or an art appraiser who assesses the kind of work you’re sitting on.

If the artist is alive, you can try contacting him or her, but be prepared for lack of engagement. Living artists rarely have the resources to buy back work from a collector, let alone the space to store more work. It’s also important to note that artworks purchased directly from living artists may not retain much or any market value unless that artist is also represented by a dealer or gallery that commands consistent prices for that artist’s work or if there is an auction record for that artist’s work. And it’s common for a collector – perhaps your great-uncle whose collection you inherited – to be an enthusiast for the work of an artist whose prices never climbed or held. This is the artwork you give away to other family members or sell yourself in the tradition of a garage sale. The chance that what you give away or sell through Facebook Marketplace turns out to be incredibly valuable and will end up a sleeper on an episode of Antiques Roadshow is a fantasy we harbor, but it’s almost never the case. The work may have some sentimental value, but that’s about it.

Professional art appraisers enter the picture when a collector needs to know the current value of artworks for tax and insurance purposes, but an appraiser can also help you determine the current value of the work for selling purposes. Again, an art dealer who sells it on may be the natural appraiser of an artwork, but they may also put you in contact with an appraiser who specializes in the type of work you want to unload. Appraisers can charge by item or hour; rates can run between $50 and $500 an hour, and the minimum cost of a single-item appraisal report can start at $250. The appraisal of a large collection or entire estate costs thousands of dollars. An independent appraiser will leave you with helpful information, but you will still have to find a buyer.

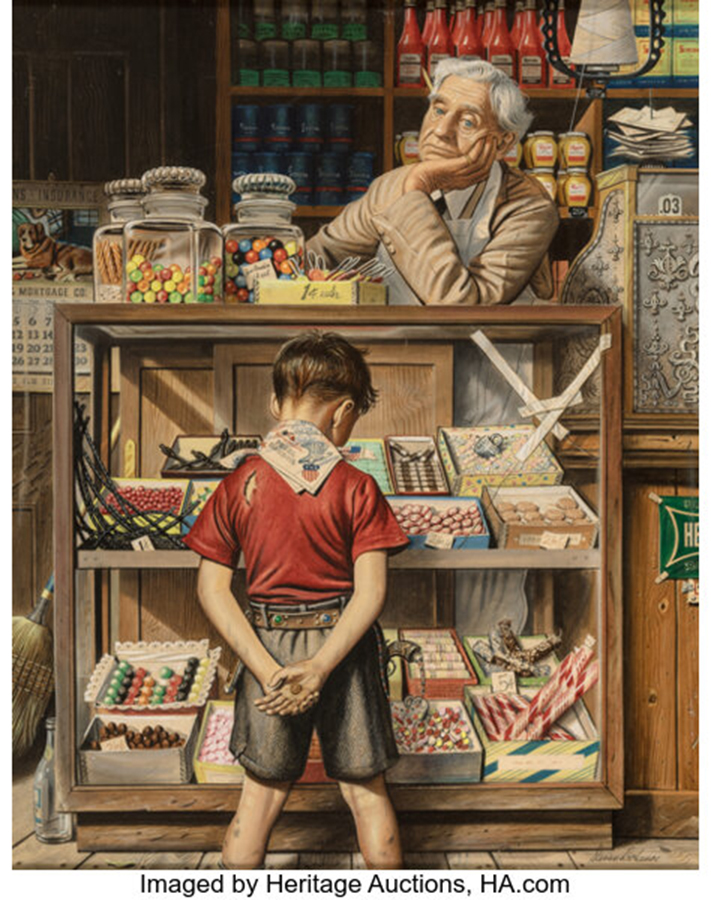

Stevan Dohanos’ ‘Penny Candy, The Saturday Evening Post Cover,’ September 23, 1944. Sold for $375,000 in a November 2022 Heritage auction.

Consider Donating to a Museum or Institution – But Only Under Certain Circumstances

The only reason to approach a museum or collecting institution (such as a university archive) is if you already know and understand the importance of the work and what holes that institution may want to fill in its collection. While collecting museums will take collections, parts of collections or individual works from established collectors or buy works directly (or indirectly, via patrons) from gallerists, artists and auction houses, these institutions rarely have the energy or resources to field inquiries from individuals with an undetermined inventory.

Thomas Moran’s ‘Entrance to the Grand Canal, Venice,’ 1906. Sold for $125,000 in a November 2022 Heritage auction.

Contact an Auction House

Works in high demand and in good condition are likely to realize higher prices at auction than on the private market. If you have evidence that the artwork carries secondary market value or you know the work has been sold at auction before, or if you have an entire collection of works of varying values, you can contact an auction house that works with art. “It may be helpful to think of an auction house as the full-service provider that it is: a gathering under one roof of appraisers, dealers, researchers and catalogers, marketers and a wider collecting audience than any one gallery,” Hettig says. “If an auction house is interested in helping you sell your collection, it can boost the collection’s profile by contextualizing and packaging it for the appropriate audience.”

Generally, auction houses charge consignors a seller’s fee of between 10 and 25 percent of an artwork’s hammer price. The auction house may choose to take some of your collection but not all of it. It also may auction your collection in stages. Given that everyone in the process wants to realize the highest price possible, be assured that a legit auction house with a solid history of working with art will approach your collection and its sale with careful consideration and a realistic understanding of its market value.

What’s hard to beat is an auction house’s outreach to the widest possible collecting audience, especially in our digital age when research and buying are at the tip of any collector’s finger and houses like Heritage maintain robust online resources and information on lots, sales, collections and collecting trends. They make it easy for any collector anywhere in the world to make a secure purchase. Serious collectors are a determined and connected cohort. If they want what you’re selling, the auction house is often their favorite venue for finding their next prize – and it may well be that very same artwork you won’t hang in your own living room.

For inquiries, contact Frank Hettig at FrankH@HA.com or 214.409.1157.

CHRISTINA REES is a staff writer at Intelligent Collector.

CHRISTINA REES is a staff writer at Intelligent Collector.