MANHATTAN GALLERY OWNER NICHOLAS BRAWER’S CHANCE MEETING WITH A BRITISH OFFICER SPARKED A FASCINATION WITH MAN’S MORE ADVENTUROUS PURSUITS

By Suzanne Gannon

MANY COLLECTORS FIND a mentor in an old masters scholar. But few have been schooled by a decorated officer in the Indian Army’s Skinner’s Horse Regiment, formed in 1803 as one of the many British Empire cavalries that patrolled the farthest reaches of the Indian subcontinent well into the 20th century.

Count Nicholas Brawer among that unique group.

The rare mentor/student relationship kicked off a career that today spans decades of expertise Brawer has filed away in a mind filled with drawers of dense detail. His command of this compendium has resulted in an array of pursuits – authorship of a definitive illustrated history of British campaign furniture, traveling the British countryside amassing collections of furniture and colonialist weaponry, stints at prestigious museums, and the opening of an immaculate gallery on New York’s East 72nd Street, in the shadow of the Ralph Lauren townhouses.

His gallery is a narrow space stocked with what he calls “sporting antiques,” gleaming objects suitable for men with deep pockets and a taste for shiny things such as the complete series of chrome-plated “Flying Goddess” hood ornaments designed by pin-up artist George Petty. They were commissioned by George Romney of American Motors for use on Nash automobiles from 1951 to 1955. The ornaments go for $3,500 each.

Visitors to the Nicholas Brawer Gallery will also find a cocktail shaker in the form of a shrapnel shell with four hand-blown glasses ($8,000), and a unique cut-glass and sterling silver cocktail shaker in the shape of a World War II-era British hand grenade ($12,000). Brawer adds that it is “to be filled with marginally less deadly contents.” There are model cars, sailplanes and boats — and a 1962 Martin Baker Mark II pilot’s ejection seat with an 80-feet-per-second ejection gun that was removed from a Royal Air Force Strategic Nuclear Bomber. Adding this item to your collection will set you back $28,000.

Featured in Elite Traveler, Super Yacht World, Departures, Forbes and Town & Country, Brawer’s merchandise has been browsed by some of Architectural Digest’s Top 50 interior designers and architects, including David Easton and the late Charles Gwathmey, as well as various rappers and music moguls, yacht-owners and titans of real estate, finance and technology.

“Nick Brawer is truly a gentleman and a scholar, and comfortable in any of the last three centuries,” says Nicholas Dawes, vice president-special collections at Heritage Auctions. “His eye for quality pierces the darkest corners of our collecting world. Who else could find such beauty and elegance in a Victorian lance?”

‘I’M AN OBJECT GUY’

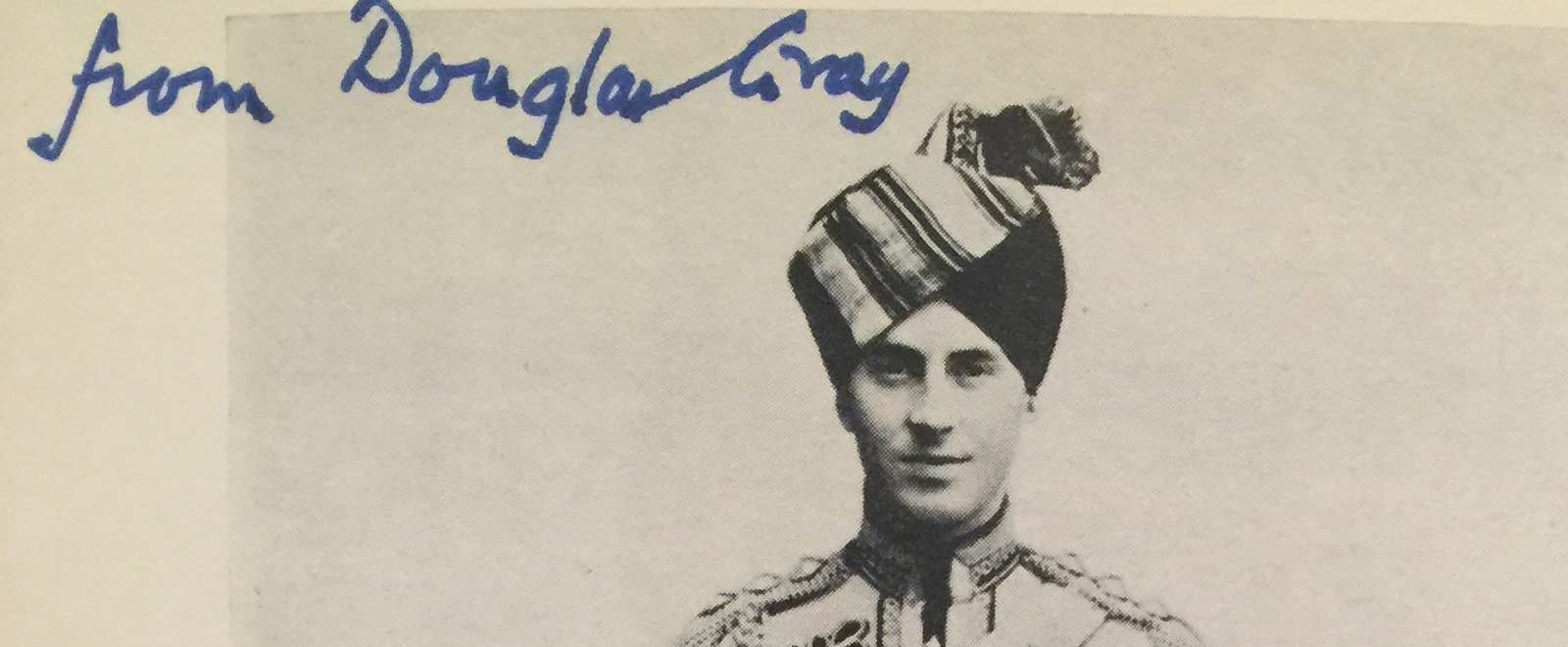

In the late 1990s while Brawer was in London researching a book, he met the man who would have a profound influence on him: Lieutenant-Colonel Douglas “Duggie” Gray, who in 1932 was posted to the prestigious Skinner’s Horse regiment, alternately known as both the 1st Duke of York’s Own Cavalry and the 1st Bengal Lancers.

On a weekday morning at his gallery, the dealer and collector passionately elaborates on his mentor’s milieu. Consisting largely of British officers and their local recruits, regiments like Gray’s reflected the belief that a multi-ethnic army could find solidarity in warfare against common enemies during colonial exploits through modern-day India, Pakistan, Burma and elsewhere.

“I spent four years with Duggie and it changed my life,” Brawer says. “He brought history alive for me. He was a man of personal charm and warmth, a linguist who had a commanding presence and great confidence. My time with him sparked an interest that has not waned.”

Over the course of many visits to the officer’s home in Hampshire, over pots of tea at the House of Lords, perusals of family photo albums featuring elephant rides, polo matches at Tidworth, and marching in the Old Comrades Day parade in a bowler, Brawer says Gray played a role in many of his career moves — to the British Empire and Commonwealth Museum in Bristol; to the Victoria and Albert Museum; to the Katonah Museum of Art; and in his becoming a safari outfitter.

Gray, who died in 2004 at 94, was a Victorian to the core, one of many in the battalions of festooned prancers who were at times more keen to indulge in extracurriculars like pig-sticking and polo, claret and cricket, than participate in military maneuvers.

The uniforms the cavalrymen wore varied in color and style but not in complexity. Highly polished black riding boots were topped with kurtas cinched with ornate cummerbunds and belts, and embellished with gold lace and buttons, gilt pouches and military braids. Mustard-yellow and black were the colors for Gray’s regiment, and handlebar mustaches and turbans were common.

But the accessory that captured Brawer’s attention was their weapon: a nine-foot bamboo shaft with a leather or rope grip that was sharpened to a deadly point – the “business end” – of armor-piercing steel. Beneath it flew the regiment’s pennants. (Gray skewered a boar with a spear like this in 1934 and won the Kadir Cup; he later had the tusks made into a hood ornament.)

“I’m an object guy,” says Gray’s mentee, waving a hand at his Manhattan inventory.

Eventually, Brawer’s interest in the Bengal Lancers landed him an invitation to a luncheon near Hyde Park. “They asked me to leave the room,” he says. “When I was called back in, I was given an honorary membership in the Indian Cavalry Officers Association.” He was the only American to get the nod.

Because they are hard to find, regimentally stamped lances from the Victorian and early Edwardian periods are the most coveted, Brawer says. “Original condition is preferred. Dried blood is quite rare indeed. Usually, surviving pennons are a century or more old.”

If they can be proven to have been used in a significant battle or a cavalry charge such as Balaclava in the Crimean War or Omdurman in the campaign in Sudan, lances from these periods can sell for between $8,000 and $10,000. Proper display consists of a crossed pair mounted on a wall, flags unfurled, or in an arrangement like an unfolded fan. Brawer owns 12 lances made in 1915 for the Government of India. He found them 20 years ago in the English countryside, and they now hang as decorations above each of his 12 dining chairs.

“I’m the guy deciding which lance has historic value,” he says. “It’s the quality and handling, the feeling of the weight. The flags must conform to the pattern book.”

THE MAGIC OF HISTORY

At the time he met Gray, Brawer was in the middle of a seven-year journey through the United Kingdom on a mission to publish British Campaign Furniture: Elegance Under Canvas, 1740-1914, which chronicles the origins, apex and decline of the portable furniture British officers brought into battle to set up camp. More often, the furniture was carried by the servants who catered to the officer, as many as 100 pieces for a single military family. Brawer published the book in 2001.

“I don’t follow trends,” Brawer says. “Trends come and go. But knockdown furniture is timeless. It’s much more beautiful than Georgian, Regency or Edwardian furniture and it’s the only English furniture that tells a story.”

Brawer marvels at the wizardry of the traveling cabinet constituted by parts like 12 mahogany dining chairs with inlaid brass that fold into a box. “It’s the original Ikea,” he says.

Though signed English furniture is not as easy to find as signed Scandinavian pieces, he says, provenance can originate out of the English officer who used it.

“A piece comes alive and it’s fascinating. It’s the hook that tells the best stories. For generations, the sun never set on the British Empire. They ruled a quarter of the earth and maintained their lifestyle while doing so. These pieces set the old military social hierarchy.”

But after the Boer War, the collector says, much of the “domestic” equipment of the Victorians’ portable empire became impractical. Artillery was eclipsing the cavalry.

Collectors should look for pieces, usually made of mahogany, teak or oak, signed by a maker and that include the name of an officer who used it, he advises. By far, the most extraordinary maker was the Irishman Gregory Kane, who reached his apogee between 1829 and 1865 and displayed his works at several Royal Dublin Society Exhibitions, inspiring awe with portable houses that contained sofas, sideboards, loungers, chairs, card tables, pier glasses, toilets, beds, wardrobes, curtains, cooking ranges and zinc roofs that rolled up. One such model accommodated a family of six, fit into eight boxes, and when assembled, had the appearance of a brick cottage with stained-glass windows.

“If you owned his ‘Travelling Cabinet’ and his ‘Portable House,’ you probably didn’t need anything else in life,” says Brawer, who, with his wife, uses their portable furniture every day. “We live with it – we have chairs and a bookcase and a chest of drawers as part of our house. It’s usable today because it was meant to withstand warfare.”

Brawer is tipped off to a fake (or what he calls an “innocently doctored but misperceived” chest of drawers) when its feet are something other than the original, screw-on “buns” that would have been placed in oil (while in camp) to deter ants. “The feet must be flush,” he says, “so that they could be packed flat and folded into the ship. Post World War II, some of these chests were cut in half and affixed with brass fittings out of nostalgia.”

INSATIABLE CURIOSITY

His third interest these days marks a departure from the British Empire and its colonial ambitions but concerns another nation’s history of warfare. Adding a new sheen to his shop are high-powered binoculars manufactured by Toshiba, Nikon, Minolta and Olympus and mounted on Japanese battleships in World War II.

“I’ve sold about 40 for penthouses just in this neighborhood,” he says, tracing a circle in the air with his index finger. Once painted in drab military colors, the binoculars have been restored to their metallic gleam and then treated with a proprietary coating Brawer says is neither powder coat, paint nor lacquer and that must be meticulously applied by hand over the course of a minimum of six months. “I feel like a free man now that I no longer have to polish.”

He says the binoculars range in price from about $15,000 to “many multiples of that.”

Brawer possesses an insatiable curiosity and a zealous, comprehensive knowledge of his subjects. But he also owns an imagination intoxicated with romance that, through fact and fantasy, transports him back to an earlier time. Whether peering through binoculars to find a ship awash in the splash of a torpedo or examining an entire drawing room housed in a pine box only one foot deep and three feet wide, he pays homage to those he’s brought to life in his mind.

He’s more than just an object guy. Thanks to his mentor, Brawer today is master of an era – or two.

SUZANNE GANNON is a New York writer whose work has appeared in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, Town & Country and Art + Auction.