THE ETERNAL WISDOM OF BEAVIS AND BUTT-HEAD

By Christina Rees

As much as we’d like to think we can take measure of the present and predict the future, very few have a gift for it. When I was in my early 20s, I caught the debut of Beavis and Butt-Head on MTV and then stuck with it for years, but I couldn’t have guessed its creator, Mike Judge, would turn out to be the guy who over the next three decades would show us who we really are and where we’re headed. Along with Beavis and Butt-Head, Judge’s Office Space, King of the Hill, Idiocracy and Silicon Valley have offered up the most incisive depictions of humanity in modern-day storytelling.

Judge’s assessment of our direction is bleak, pointed, often compassionate, and funny as hell. He gets that as individuals we’re pretty hapless and well-meaning, but as a species we’re taking ourselves down some dark pathways. There’s a good reason Judge’s movie Idiocracy, woefully overlooked upon its release in 2006, is now considered the most prophetic and accurate portrait of our late-stage democracy to come out of Hollywood. Its cult status transcends any cult. It turned out to be frighteningly on-the-nose and is mentioned as often as Orwell’s 1984 and Huxley’s Brave New World as keys to our current moment. Idiocracy is a sci-fi horror show parading as absurdist comedy (and it kicked its progenitor, Terry Gilliam’s satire Brazil, out of the top slot of this uncomfortable and brilliant category). Judge is, in other words, the kind of prophet who crops up once in a lifetime. It’s a massive bonus that he also happens to make us laugh.

Beavis and Butt-Head rolled out to an unsuspecting national audience via MTV’s experimental after-hours adult show Liquid Television in 1992 and returned as a series in 1993. At the time, Judge was a disillusioned office worker living in Richardson, Texas. Animation was his Hail Mary play. The show’s setting reflected Judge’s assessment of directionless kids growing up in a generic suburb. The series’ crudity and profanity were always telling: We just didn’t yet fully understand the profundity of its portrayal of two 15-year-old delinquents (as parentless as Charlie Brown) who walk around their neighborhood in a daze of directionless chaos.

Feb. 16, 2023

Online: HA.com/40218a

INQUIRIES

Jim Lentz

214.409.1991

JimL@HA.com

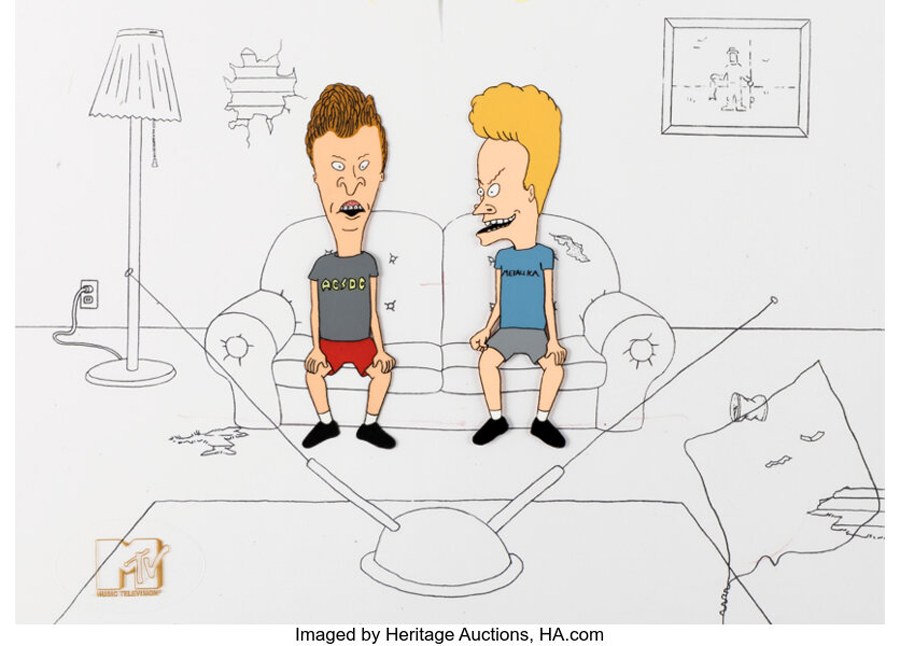

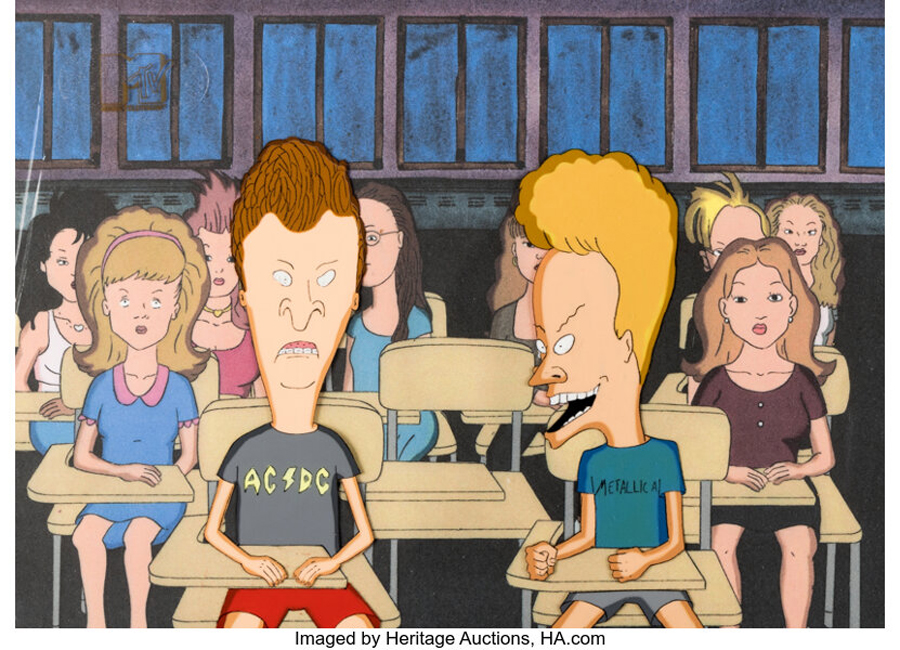

They turn live frogs into baseballs, set things on fire and chase sugar highs. They’re innocent and depraved. In between misadventures around their streets and high school, they sit on a beat-up sofa in a beat-up living room and watch MTV music videos, which they critique with the oddball, incoherent wisdom of noble savages. Like the show itself, Beavis and Butt-Head are so dumb, they’re weirdly astute.

The series was an instant hit; it, along with The Simpsons, launched a whole era of grown-up animated comedy and set the stage for another smart-dumb masterpiece, Trey Parker and Matt Stone’s South Park, which debuted in 1997. Last summer, Parker told the Los Angeles Times: “For us, it was Beavis and Butt-Head. That was the time where we were like, ‘We could do that.’ We never watched The Simpsons and said, ‘We can do that.’ Beavis and Butt-Head had this really handmade feel. We really bonded over that.” And as Parker and Stone have said to their friend Judge: “Beavis and Butt-Head is like the blues. It’s the same thing over and over, but it’s good.” And however consistently funny it was, it also served (albeit unconsciously) as a bit of a warning from Judge: We’re not taking much responsibility for the next generation, and we’re all gonna end up paying the price.

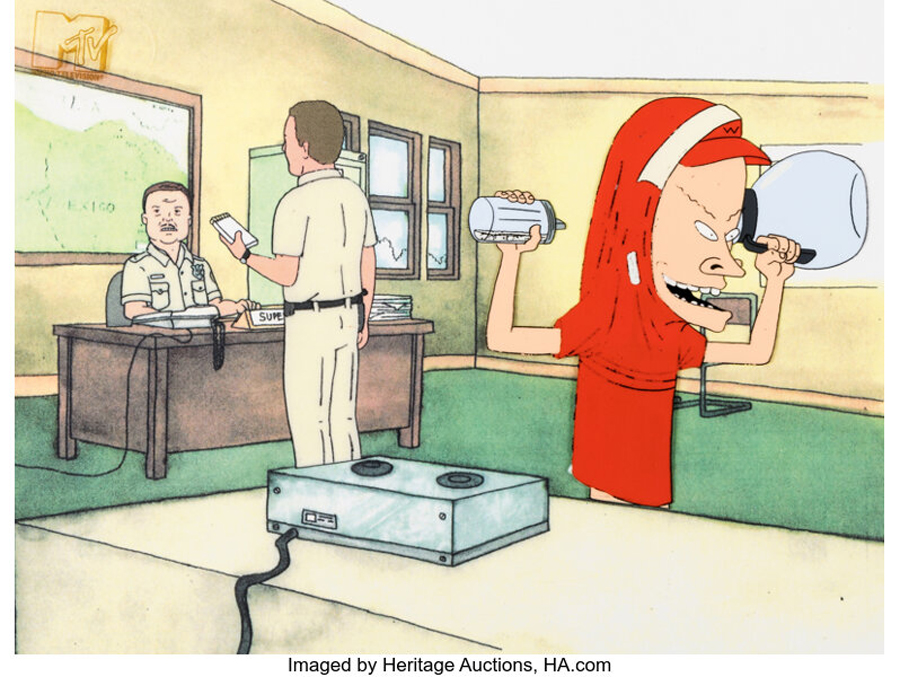

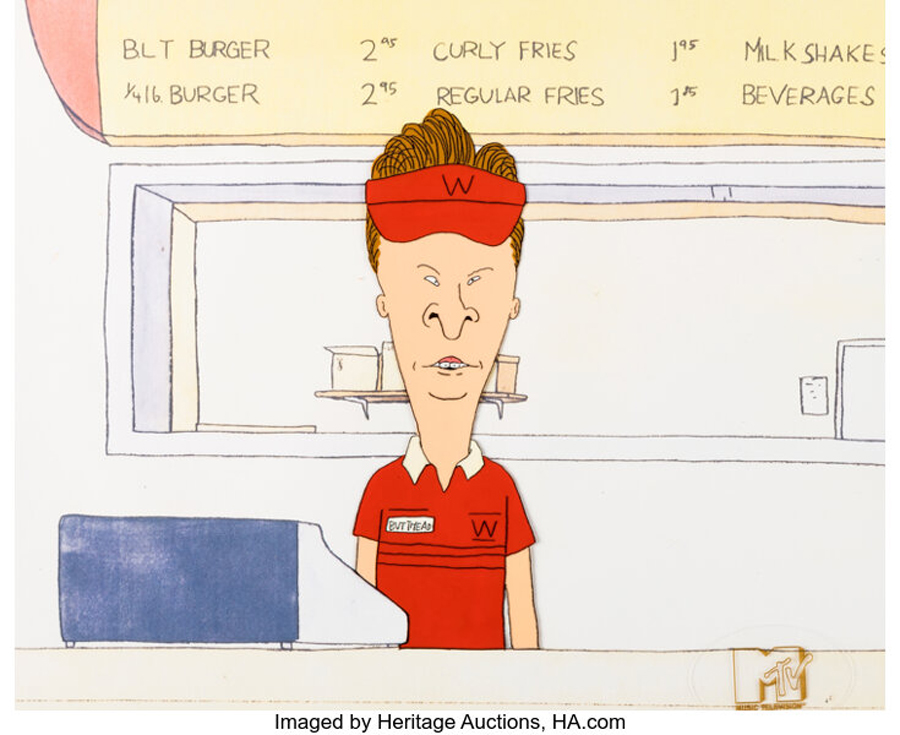

In the early ’90s, studio animation was still created by hand, including the original run of Beavis and Butt-Head. The raw, jumpy aesthetics of the show reflect the stunted and jittery brainwaves of its two antiheroes. I was thrilled to see original cels from the show arrive at Heritage as part of its sweeping auction of MTV and Nickelodeon production art (also featured in the February 16 event are cels and artwork from other key series, including SpongeBob SquarePants, The Ren & Stimpy Show, Rugrats and Æon Flux). It’s the first targeted auction of animation art from these studios, and it features some of the last hand-painted production cels before the industry went digital. It’s odd to characterize a cel from Beavis and Butt-Head as luxurious, but hand-painted cels carry the charm and impulse of a human animator, and the Beavis and Butt-Head team, working under Judge, was tight and productive.

Among the 33 Beavis and Butt-Head production cels in the auction you’ll find some of the most iconic imagery from the show’s original run, produced from 1993 to 1997: Butt-Head standing open-mouthed behind the cash register at Burger World; Beavis with his shirt hiked over his head as he shouts, “I am the great Cornholio!”; the boys creating havoc at school, in empty lots, in front of the television. These are from the classic scenes, from the episodes we most associate with the show (and Judge’s early twisted and juvenile imagination), including “Tainted Meat,” “Citizen Butt-Head,” “Just for Girls,” “Bungholio” and more. A cel featuring the two standing on the street outside Beavis’ house, taking turns pressing a 9-volt battery against their tongues took me right back to my 20s, in limbo after college as I watched the show from my own beat-up couch and cry-laughed into a microwave dinner after a double shift at my restaurant job. I wondered if I’d ever figure out how to grow up and if it would be worth it if I did.

Even the most straightforward compositions of the two sitting on that fraying couch, lobbing insults at a Winger video (and each other) evokes the very heart of the show, and through it you can hear Butt-Head’s baritone, mouth-breather drawl and Beavis’ manic giggle. These two never stopped laughing at anything, no matter how grim or corrosive the situation. Their blunted, slow-brained pleasure in all things made us laugh right along with them.

There’s a lesson in there somewhere. Mike Judge, prophet and seer, is very good at letting us forget that, but it’s there.

CHRISTINA REES is a staff writer at Intelligent Collector.

CHRISTINA REES is a staff writer at Intelligent Collector.