FROM MOONS AND METEORS TO THE SUN AND STARS, THE WONDERS OF THE COSMOS HAVE INSPIRED ARTISTS THROUGHOUT THE AGES

By Andrew Nodell | August 19, 2025

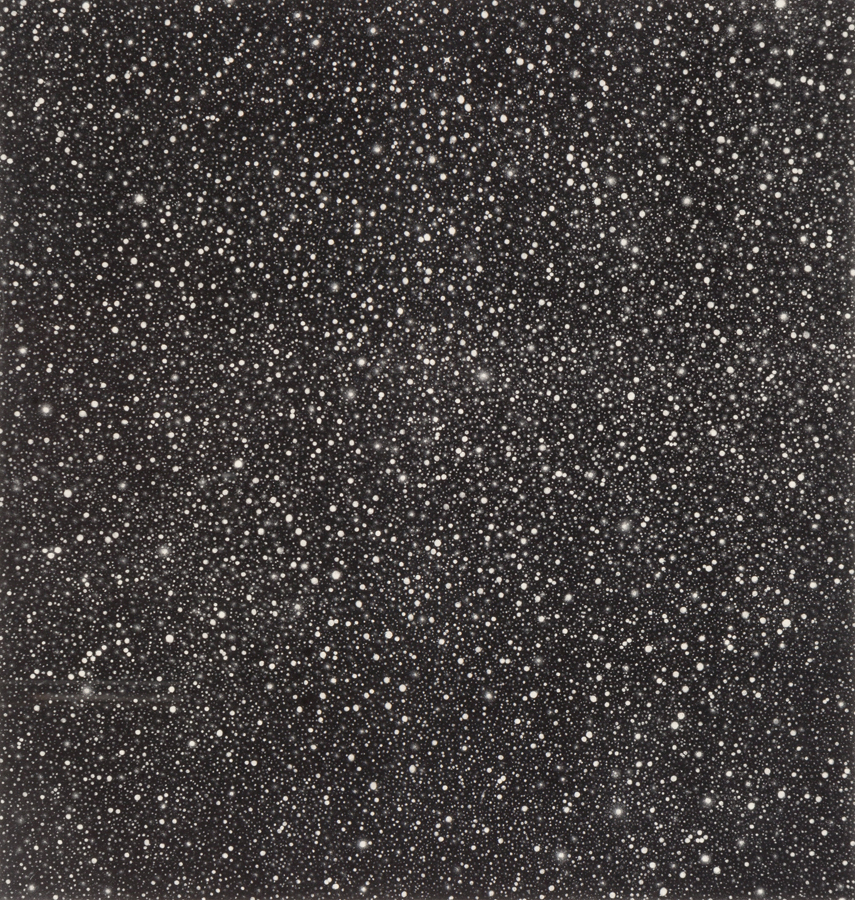

Since the dawn of time, humans of all cultures and civilizations have been fascinated by the wonders of space. And still today, the solar system’s celestial bodies can leave even the most jaded terrestrial awestruck. Likewise, for millennia, artists of all forms have found inspiration in the universe. From the prehistoric Nebra Sky Disc – the oldest known depiction of the cosmos – to Chesley Bonestell’s fantastical midcentury lunar landscapes and Vija Celmins’ contemporary night sky drawings, here are 13 ways humans have interpreted the majesty of the heavens.

This 12-inch bronze artifact known as the Nebra Sky Disc is our earliest known map of the stars. Photo: Public domain.

Nebra Sky Disc (c. 1600 B.C.E.)

Produced in the Early Bronze Age, some 3,600 years ago, the Nebra Sky Disc was discovered buried in a hillside in Central Germany in 1999 by two trespassing treasure hunters and has since been shrouded in mystery and controversy. The disc’s existence became public in 2002 following a sting operation that led the German State Archaeologist of Saxony-Anhalt to the looters, whose haphazard pillaging damaged the disc. Now held in the collection of Germany’s State Museum of Prehistory in Halle, the artifact’s initial intent is unknown. Still, archeologists have concluded it was constructed in parts over several generations and could have had ceremonial significance. Its blue-green patina is embossed with gold shapes that represent either a full moon or the sun, stars, and a crescent moon. Two golden arcs on the side offer an impressively accurate representation of the angle of the sunrise and night sky between the summer and winter solstices. However, some scholars have speculated these to be a comet, a rainbow, or even a sickle. The cluster of seven stars is commonly interpreted as Pleiades, or Seven Sisters. Regardless of its original purpose, the Nebra Sky Disc is tangible evidence of our collective wonder of the cosmos since time immemorial.

A plate from Andreas Cellarius’ 1660 star atlas ‘Harmonia Macrocosmica.’ Photo: Public domain.

Harmonia Macrocosmica (1660)

Andreas Cellarius

Harmonia Macrocosmica, an atlas of the stars from Dutch-German cartographer and cosmographer Andreas Cellarius, maps the structure of the heavens in 29 richly illustrated double-folio spreads. Here we see various interpretations of our solar system, including Ptolemy’s Earth-centered model, Copernicus’ sun-centered one, and Tycho Brahe’s hybrid geocentric and heliocentric model. One of the most beautifully illustrated atlases from the Dutch Golden Age of cartography (c.1570s-1670s), Cellarius’ atlas stands as an artistic masterpiece and offers a glimpse into the 17th-century understanding of the solar system.

In ‘The Astronomer’ by Johannes Vermeer, a scientist consults a version of Dutch cartographer Jodocus Hondius’ celestial globe. Photo: Public domain.

The Astronomer (1668)

Johannes Vermeer

Contemporaneous with the Cellarius atlas, Vermeer’s 1668 work The Astronomer provides another window into the intellectual spirit of the Dutch Golden Age. The canvas, which is held by the Louvre in Paris, reflects the 17th century’s fascination with the cosmos and humanity’s place within it. The painting shows a scholar, believed by some to be the scientist Antonie van Leeuwenhoek, leaning toward a celestial globe as light streams through a window – a hallmark of Vermeer’s mastery of illumination. While this masterwork does not actually show the sky, the artist’s subtle details, like an open book on astronomy and a globe set upon the tapestry-draped table, illustrate the era’s thirst for knowledge both within and beyond Earth’s atmosphere.

J.M.W. Turner painted ‘Moonlight, a Study at Millbank’ in 1797, the year after he exhibited his first oil painting at the Royal Academy. Photo: Public domain.

Moonlight, a Study at Millbank (1797)

J.M.W. Turner

Painted when Turner was in his early 20s, this work captures a tranquil, moonlit view along the Thames near Millbank in London, where the young artist lived and studied. A romantic departure from the more scholarly 17th-century depictions of the night sky, Moonlight shows a full moon floating gracefully over a city not yet polluted by incandescent light. Now in the collection of the Tate Gallery, this oil on mahogany board painting demonstrates Turner’s fascination with natural illumination and shifting tones of the night sky – motifs that would later become central to his more dramatic explorations of light and color.

Landscape master Frederic Edwin Church’s ‘The Meteor of 1860’ was recently acquired by the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art in Connecticut. Photo: Public domain.

The Meteor of 1860 (1860)

Frederic Edwin Church

Church’s The Meteor of 1860 captures a rare celestial occurrence that captivated observers across the United States on the night of July 20, 1860. This extraordinary event – a brilliant procession of fireballs streaking across the sky – was widely documented in newspapers and personal accounts of the time, inspiring awe at a time when science and wonder often intertwined. Church, a leading figure of the Hudson River School, translated the phenomenon into a luminous, atmospheric study at a time when photographic technology couldn’t have adequately captured its splendor. The painting not only reflects the 19th-century fascination with nature but also stands as one of the earliest known artistic records of a specific meteor event, forever preserving a fleeting moment when heaven and earth seemed briefly connected.