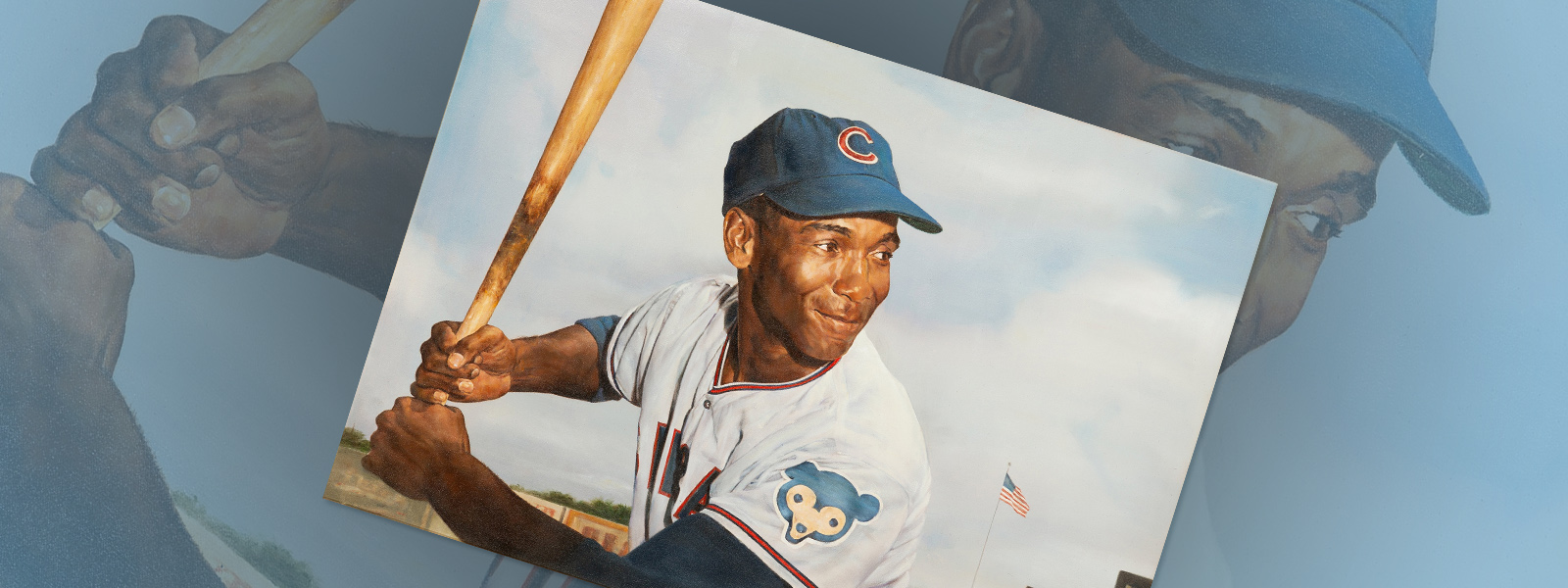

ERNIE BANKS’ FIRST PRO CONTRACT AND BASEBALL HALL OF FAME RING BOOKEND HISTORIC AUCTION OF MEMENTOS FROM EVERYONE’S FAVORITE CHICAGO CUB

By Robert Wilonsky

Ernie Banks’ name first appeared in his hometown paper on May 1, 1949 – as “Ernest Banks,” the name given to him by parents Eddie and Essie Banks upon his birth on January 31, 1931. The Dallas Morning News mentioned him as the second baseman of the hometown Dallas Black Giants, who squared off that afternoon against the Amarillo Colts at the late Burnett Field. Banks, a Dallas native not yet a Chicago legend, was all of 18 at the time and still a student at Booker T. Washington High School, where he lettered in basketball (he averaged 15 points a game), football (he scored 22 touchdowns his junior and senior years) and track – only because Booker T. didn’t have a baseball team. This is why Banks suited up that spring as a Black Giant, a team whose return to the Negro leagues in 1949 was short-lived. Formed in 1908, the Black Giants disbanded the year Banks made his professional debut.

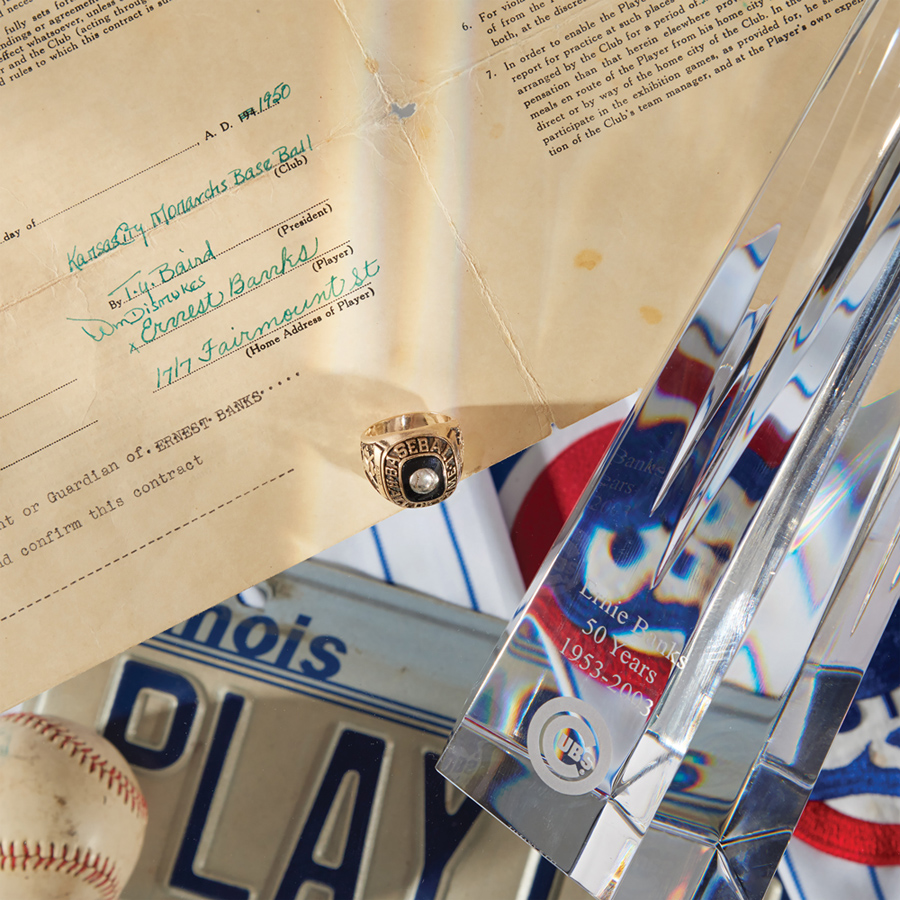

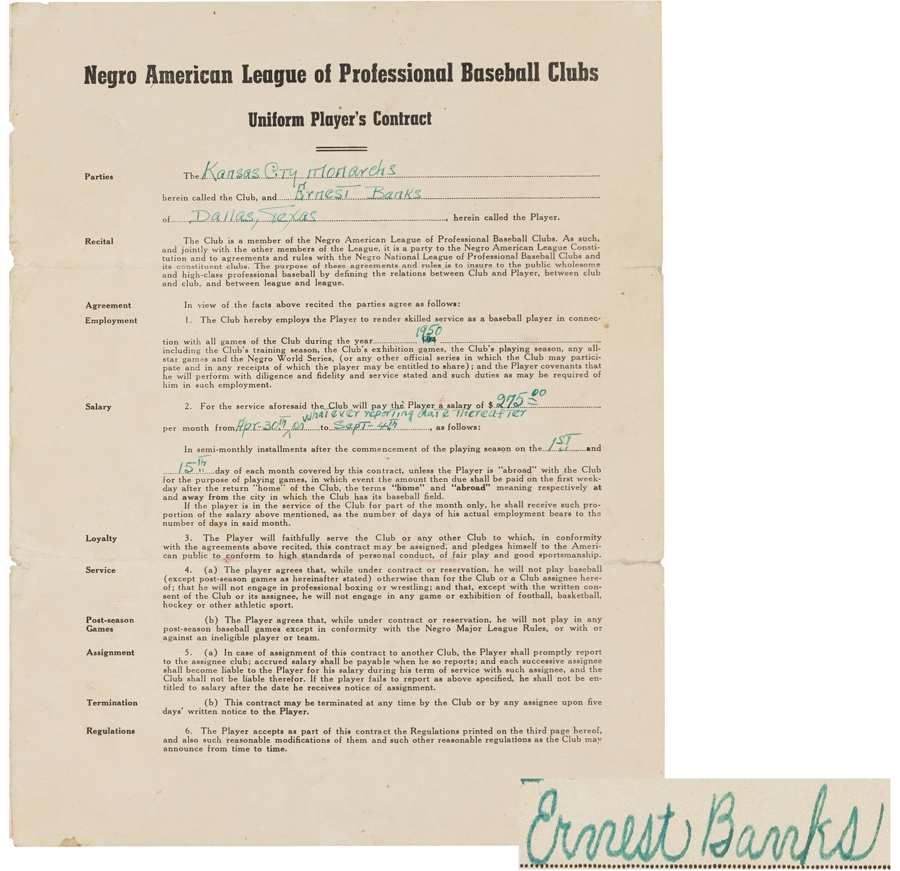

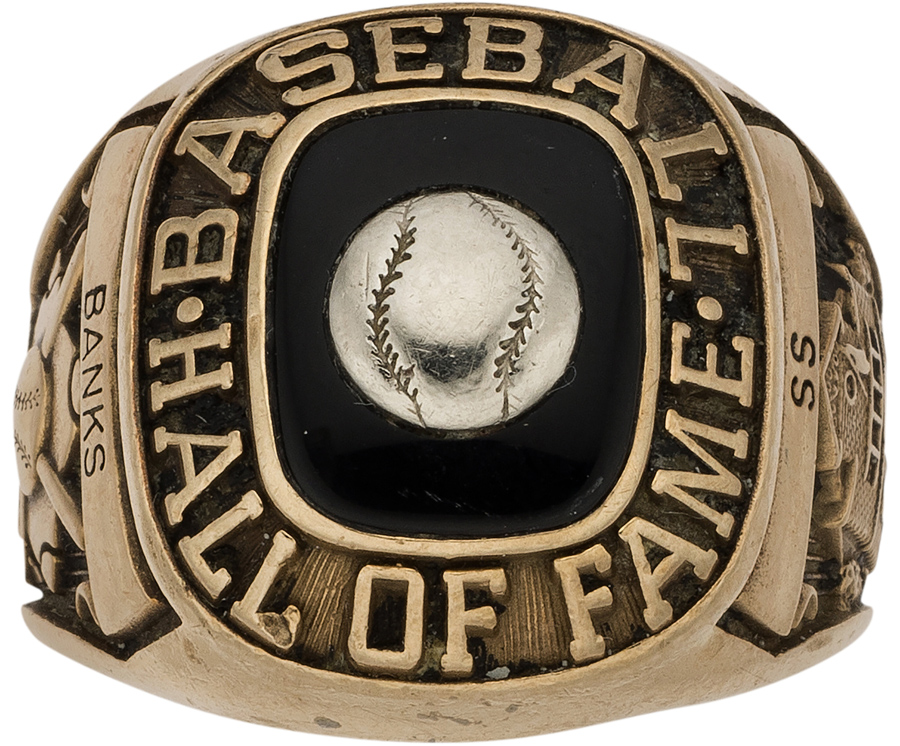

Just a few of the three dozen items from The Ernie Banks Collection available in Heritage’s August 19-20 Summer Platinum Night Sports Auction, including Banks’ first professional contract and his Baseball Hall of Fame ring

During summers between semesters, Banks traveled with those Colts of Amarillo at the urging of Negro leagues player-manager William Blair, the pitcher-turned-newspaper publisher for whom there’s a park named in Dallas. Banks, the most beloved and revered Chicago Cub of all time, wrote in his 1970 autobiography Mr. Cub that during those road trips, he ran into James Thomas Bell – the future National Baseball Hall of Famer better known as “Cool Papa,” whom history recalls as perhaps “the fastest man ever to play the game of baseball.” Banks would later recount that Blair and Bell informed the Kansas City Monarchs – “at the time the Yankees of black baseball,” Banks wrote – there was a kid from Dallas worth a look.

Two reps from the Monarchs came to the Banks’ Dallas home before Ernie’s senior year started. They told Ernie and his parents that once he graduated high school in the spring of 1950, there would be a roster spot waiting for him with the Monarchs for which he would receive $275 a month – “big, big money to two people who had worked hard all their lives and never even come close to earning” that much in a month, Banks wrote.

SUMMER PLATINUM NIGHT SPORTS AUCTION 50063

August 19-20, 2023

Online: HA.com/50063

INQUIRIES

Chris Ivy

214.409.1319

CIvy@HA.com

That contract is one of the centerpiece offerings of Heritage’s August 19-20 Summer Platinum Night Sports Auction – and one of three dozen items in this event from The Ernie Banks Collection, including the ring given to Banks upon his induction into baseball’s Hall of Fame in 1977. Here, too, is his watch, his golf clubs, a U.S. Open flag signed by Tiger Woods, his trademark “PLAYTWO” license plates and other mementos.

But the significance of these four sheets of paper cannot be overstated.

“He once told me he did not want to go play for a professional league,” says Regina Rice, Banks’ longtime friend and the executor and trustee of his estate. “He didn’t want to leave Dallas. But from then on, his life was simply amazing. And he remained humble throughout it all.”

Long hidden in California, these four pieces of paper launched the career of the man who entered Cooperstown’s hallowed halls in 1977. This contract served as his invitation to the world of giant ballparks filled with loud crowds and “huge dugouts” stocked with legends in the making, including his manager and former Monarchs first baseman Buck O’Neil, who later became a Cubs scout. And it helped secure him a spot on Jackie Robinson’s barnstorming All-Stars team, alongside big-league greats Roy Campanella, Don Newcombe and Larry Doby.

“Playing for the Kansas City Monarchs was like my school, my learning, my world,” Banks would later say. “It was my whole life.”

That contract also features the Banks family’s home address: 1717 Fairmount Street, which contradicts numerous biographies and newspaper stories that had the family living next door at 1723 Fairmount. It’s a minor detail, to be sure; that house and the entire neighborhood were long ago razed to become part of Dallas’ Arts District, which includes the Booker T. Washington High School for the Performing and Visual Arts. But history is still being written by documents like this one, which Rice once thought had vanished forever.

“When Ernie died in 2015, one of his friends in California went through the storage unit,” Rice says. “I knew it was there. We got there and went through everything but couldn’t find it. But I had a picture of it. So I went to one of the managers and said, ‘Hey, the contract is missing.’ The guy says he remembered seeing it – and that the president of the storage company put it on display in his office. Sure enough, that’s where it was.”

Cubs representatives met Rice at the storage unit to retrieve the contract and Banks’ honorable discharge certificate from the Army. The Cubs brought both documents back to Wrigley Field, where they were unveiled and turned over to Rice.

Banks’ Monarchs career was sidetracked in 1950 by what he called “a letter with greetings from the President of the United States” – a draft notice. As his April 1957 honorable discharge certificate notes, Private First Class Ernest Banks was transferred to the Army reserves in March 1953. His spot on the Monarchs was waiting for him. But so, too, were the Chicago Cubs.

On September 8, 1953, the Cubs bought Banks’ Monarchs contract for $10,000.

A week later, The Dallas Morning News ran the headline “Dallas Negro Set to Become First in Cubs’ Line-Up.”

On September 17, Banks played his first game in a Cubs uniform and went hitless in three at-bats. He also committed an error at shortstop.

None of that mattered. The Cubs, a founding member of the National League in 1876, had their first Black player.

Banks would play in 2,528 games wearing that uniform until his retirement in 1971. No Cub, before or since, has played more games. And he holds myriad more records for the Cubs, including at-bats (9,421), total plate appearances (10,395), total bases (4,706) and extra-base hits (1,009). He also finished with 512 career home runs, putting him at No. 23 on the all-time leaders list along with Eddie Mathews.

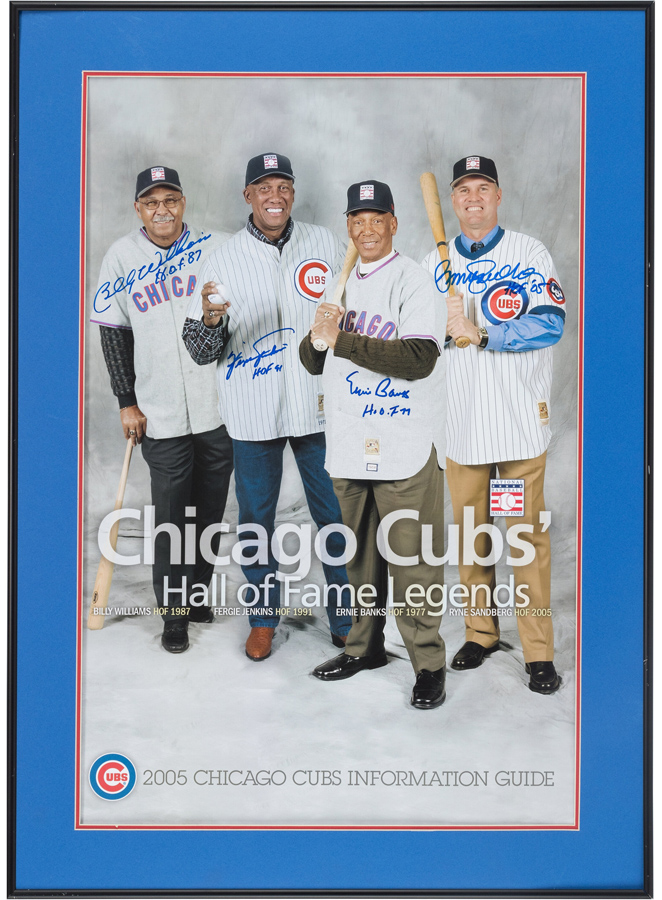

Banks started every game at shortstop for the Cubs in 1954, when he finished second in the NL Rookie of the Year voting. Banks went on to win Most Valuable Player Awards in 1958 and ’59. He accrued numerous Gold Glove Awards. He was named to 14 All-Star teams. And he was just one of three shortstops, alongside Honus Wagner and Cal Ripken Jr., named to Major League Baseball’s All-Century Team in 1999.

“The most popular Cub ever in a franchise dating to the 1870s,” The New York Times once noted, “Banks became as much an institution in Chicago as the first Mayor Daley, Studs Terkel, Michael Jordan and George Halas.”

Upon his induction into the Hall of Fame in 1977, Banks reminded fans why he was so beloved – and why he loved the game he played since he was a kid in Dallas.

“We’ve got the setting: sunshine, fresh air, and we’ve got the team behind us,” Banks said. “So let’s play two.” The crowd, filled with Cubs fans, roared with delight. “This will always be the happiest day of my life.”

If that Monarchs contract is the beginning of Banks’ pro career, the Cooperstown ring represents its end; they’re the most significant bookends of one of baseball’s most remarkable careers. Rice says Banks would want Cubs fans to have them both.

“He loved, loved, loved, loved the Cubs – I mean loved,” Rice says. “He didn’t need anything else. He didn’t make a big deal out of any of it. Ernie said you have to learn to be content. He said, ‘I don’t need much. I don’t need these things. I will never forget anything.’”

ROBERT WILONSKY is a staff writer at Intelligent Collector.

ROBERT WILONSKY is a staff writer at Intelligent Collector.