MUSEUM-QUALITY WORKS BY FABERGÉ AMONG THE MANY IMPERIAL GEMS IN HERITAGE’S INAUGURAL SALE DEDICATED TO RUSSIAN ART

By Christina Rees

The Russian Revolution of 1917 is one of the most studied and remarkable periods of change, as the Bolsheviks sought to erase nearly 300 years of Russian imperial culture steeped in rich traditions and geopolitical influence, and to overthrow Tsarist rule that stretched back yet another two centuries. Pre-Soviet Russia was awash in extraordinary art and culture, and the fateful revolution of 1917 resonates to this day; the years between then and now have provided us with the kind of perspective that only comes via subsequent unfolding histories and the slow march of time. What has the world lost and gained in those years, and what legacies, aesthetics and traditions from Russia’s profound and fascinating past have endured through careful preservation – if not grown even more valuable?

May 17, 2024

Online: HA.com/8150

INQUIRIES

Nick Nicholson

212.486.3570

NickN@HA.com

On May 17, Heritage presents Imperial Fabergé & Russian Works of Art – its first auction dedicated to the country’s stunning cultural and material history. One focus of the auction centers on objects, archives and collections that are connected to the last imperial family of Russia, the house of Romanoff, and members of the extended family. The auction is built from private collections, with highlights including museum-quality works by Fabergé made for the Romanoffs, as well as Russian paintings, icons, porcelain, furniture and Romanoff archival materials from the Estate of Princess Maria Romanoff.

“It is rare for any auction house to have more than one or two pieces with Imperial provenances that are new to the market in a sale,” says Nick Nicholson, Heritage’s Senior Specialist in Russian Works of Art. “But to have 25 such pieces is an embarrassment of riches, especially when many of them are masterpieces of the 18th, 19th and early 20th centuries. Heritage is honored to have been chosen by the Romanoff and other prominent estates to offer these works, many not seen in public for decades, and pleased to have been selected by major collectors in the field to assemble this extraordinary sale.”

A group of more than 300 images from circa 1870-1940 of various members of the Russian Imperial family, including Emperor Nicholas II and Empress Alexandra, the Dowager Empress Maria Feodorovna, and the Grand Duchesses Olga and Xenia.

The Romanoff objects that come to Heritage have traveled over oceans and time. In 1917, members of the extended family, including the Grand Duchess Xenia Alexandrovna and her children, left Petrograd for the south, taking some of the family’s treasured pieces. They arrived at Ai-Todor where they joined the Grand Duchess’ mother, the Dowager Empress, and her sister Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna, who had been expelled from Kiev by the provisional government and sent to Crimea. This branch of the Romanoff family and other members of the family, who had also fled south with their valuables, were placed under house arrest and were unable to leave until 1919, when England’s King George V sent the British ship the HMS Marlborough to bring them and their belongings to Great Britain. Many of the objects Heritage will offer took this journey with the family.

Other treasures in the auction came via Romanoff family members who were already abroad at the onset of World War I and couldn’t return to Russia. Some pieces in the auction were presented by the Romanoff family to foreign officials before and after the Great War and the Russian Revolution, and still others were seized by the Soviet Government after the Revolution and sold abroad. Some other works were collected by the Romanoffs in exile, as they sought to reacquire objects that had belonged to the family before the Revolution in an effort to restore their family legacy.

What follows is a selection of Romanoff family treasures available in Heritage’s May 17 Imperial Fabergé & Russian Works of Art Signature® Auction.

In the 1940s, two women gave birth on the same day in the same California maternity ward; one of them was Princess Vasili Romanoff, the wife of a nephew of Russia’s last Tsar, Nicholas II. The women and their families became fast friends, and within a few years Prince Vasili revealed a trove of Russian objects inherited from his grandmother, the Dowager Empress Maria Feodorovna, which were brought out of Russia with the family during their escape from the Bolsheviks. The young prince Vasili; his mother, Grand Duchess Ksenia; the Dowager Empress and many Fabergé treasures had traveled from Crimea to safety abroad. These objects, last seen publicly in 1996 as part of the bicoastal landmark museum exhibition Fabergé in America, are offered at auction for the first time on behalf of a family that has preserved them for more than 75 years.

Highlights from this private California collection include an egg-shaped, gold-mounted frame belonging to an extremely small group of egg-form frames produced by Fabergé in the workshop of Mikhail Perkhin before 1899. The frame’s Imperial provenance and the presence of its original presentation case set it apart from the few other extant models that are in institutions and private collections. This piece was likely a commission, and in a photograph featuring Queen Alexandra and her sister the Dowager Empress, it can be spotted on a desk.

This clock epitomizes Fabergé’s Louis XVI revival style at the turn of the century. It entered Fabergé’s stock in 1894 and may have been purchased by or gifted to the Grand Duchess on the event of her marriage in August of that year. The clock and other Romanoff family treasures that traveled from Russia were given to Prince Vasili for safekeeping before 1947.

Fabergé’s animals have been collector favorites for more than a century, and with good reason. This beauty is one of a surviving number of composite carved hardstone Fabergé objets de fantaisie animal forms that took off with the arrival of the stone carvers Kremlev and Derbyshev from the Urals. Examples such as this, mounted with detailed gold feet, came from the workshops of Henrik Wigström.

This piece belongs as much to the genre of Fabergé flower and plant studies as it does to the firm’s objets de luxe. It was purchased on February 7, 1901, by the Dowager Empress for her own collection. Gum pots were an Edwardian desk necessity, used for both stamps and envelopes, and this one appears to have remained with the Dowager Empress at Hvidore, her Danish estate. As a result, it was still in her possession after the Russian Revolution. The objects belonging to the Dowager Empress were divided between her daughters, Grand Duchess Xenia and Olga Alexandrovna, and the offered lot was likely sold by one of them to someone in the trade after 1924. The spectacular gum pot ended up in a private collection and was sold at auction in 2018 as “possibly attributed” to Fabergé.

Tsesarevich and Grand Duke Alexander Nikolaevich commissioned this lamp to commemorate the much longed-for recovery of the Tsesarevna and her son the Grand Duke in a period of family ill health and grieving. It was to be placed before the tomb of the young Grand Duke’s patron, Saint Metropolitan Alexis of Moscow, whose relics had been venerated within the Church of Saint Alexius built within the Chudov Monastery of the Kremlin since 1485. Confiscated by the Soviets and sold abroad, the lamp has not been seen in public since 1980.

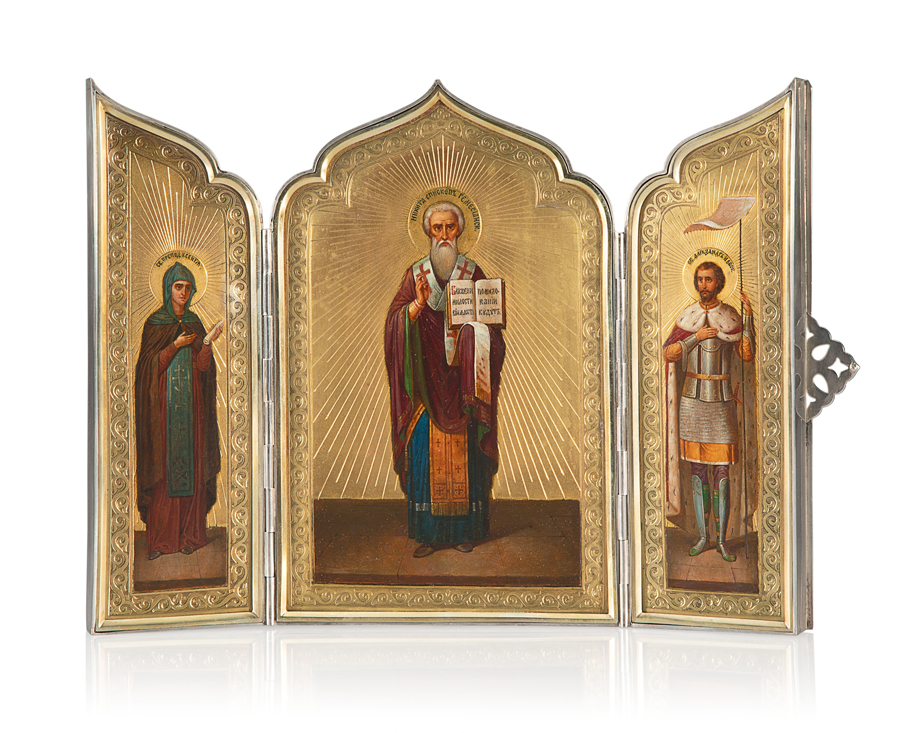

This icon is one of seven ordered by the Grand Duchess Xenia Alexandrovna and her husband, the Grand Duke Alexander Mikhailovich, to commemorate the births of their children. These skladen, or icons of the patron saints of each of their children, were ordered in advance of the births and the side panels prepared ahead, with the central panel left blank in anticipation of the birth and the announcement of the sex and name of the child. Prince Nikita was born January 4, 1900, at the family palace on the Moika Canal in St. Petersburg. After 1917, he traveled with this icon and kept it throughout his life. On Prince Nikita’s death the icon was inherited by his son Prince Alexander. Prince Alexander kept his father’s icon with him until his death in London in 2002.

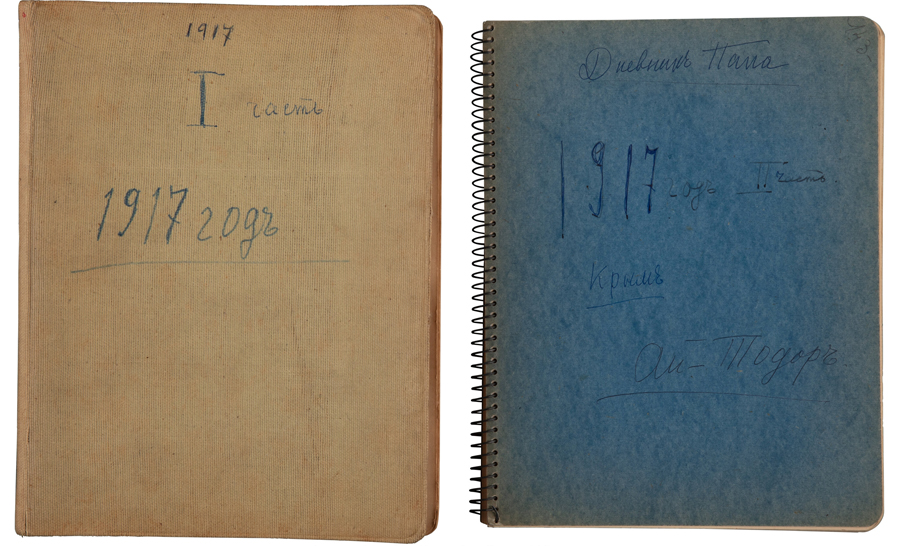

These unpublished diaries offer a day-by-day account of the last year of the Empire, including the sudden upheavals of the February Revolution. Young Prince Nikita and his mother were forced to leave Petrograd and head to Crimea for safety, where they lived in relative calm until the October Revolution, also detailed in these pages. The family ended up under house arrest with other members of the Imperial family. The pages are filled with observations of the last days of Imperial Russia, and the prince notes many events that were not yet known to the public, including details of the circumstances of their departure from Petrograd: “… we are taking very few things, the rest we are hiding around in pantries and wardrobes. Probably will go to Crimea tomorrow, but everything will be decided tomorrow…”

Born Princess Maria Immacolata Valguarnera di Niscemi, Princess Maria – or “Mimi,” as she was known – launched a successful jewelry design business in the United States and in 1971 married Prince Alexander Nikitich Romanoff, the son of HH Prince Nikita Alexandrovich of Russia and the former Countess Maria Illarionovna Woronzoff-Dashkoff. The couple became socially prominent in New York and were well known as serious collectors to auction houses and dealers around the world. According to Prince and Princess Romanoff, this portrait of Catherine the Great was a wedding gift from their friend Margaretta “Happy” Rockefeller, wife of Vice President Nelson Rockefeller. Though attributed to Christinek, the painting is taken from Russian artist Feodor Rokotov’s three-quarter-length portrait of the Empress painted in 1763, which is in the collection of the State Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow. Property from the Estate of Princess Maria Romanoff will be offered across several Heritage auctions in the coming year.

Go here for the full list of lots in Heritage’s May 17 Imperial Fabergé & Russian Works of Art Signature® Auction.

CHRISTINA REES is a staff writer at Intelligent Collector.

CHRISTINA REES is a staff writer at Intelligent Collector.