COMIC ART EXPERT JOE MANNARINO EXPLAINS HOW COLORFUL BROOKLYN NATIVE PAINTED ON HIS OWN TERMS

Interview by Greg Smith

SPECIAL REPORT

- MAIN STORY

- CHRIS CLAREMONT

- FRANK FRAZETTA

- VIDEO GAMES

- PULPS

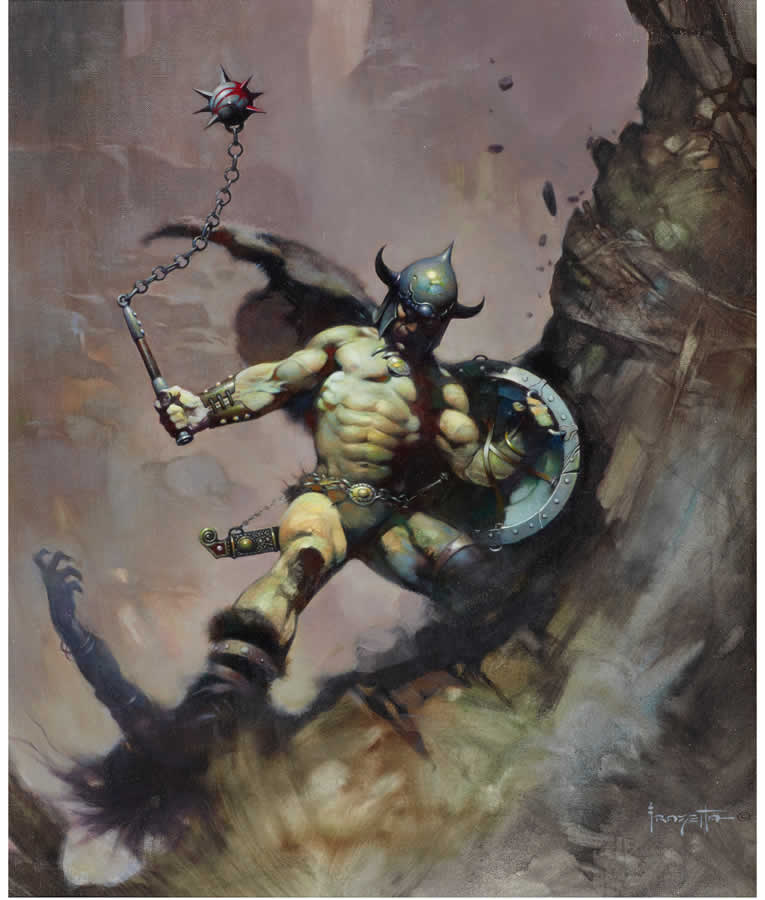

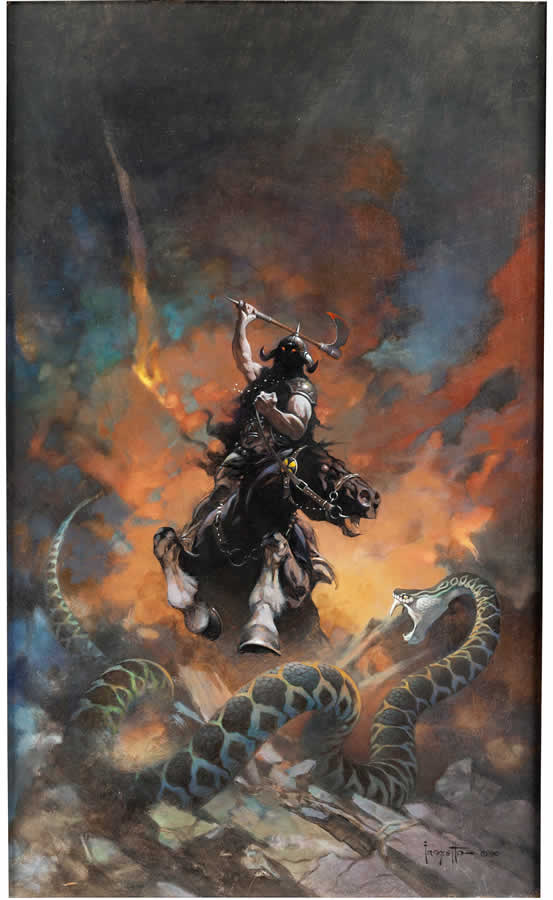

In the realm of science fiction, there is no artist that flies higher than Frank Frazetta.

Enlarge

Probably best known for his depictions of Conan, Tarzan and John Carter of Mars, Frazetta’s genesis and lifelong love affair in the industry was found in comics, as he lent his pen and brush to titles like Famous Funnies, Li’l Abner, Johnny Comet and assisting on the Flash Gordon daily strip. But Frazetta (1928-2010) was unlike many other illustrators of his time. He knew and believed he was the best, and this magnitude of confidence drove his career through sometimes bumpy roads that ultimately led to the promised land of fame and notoriety.

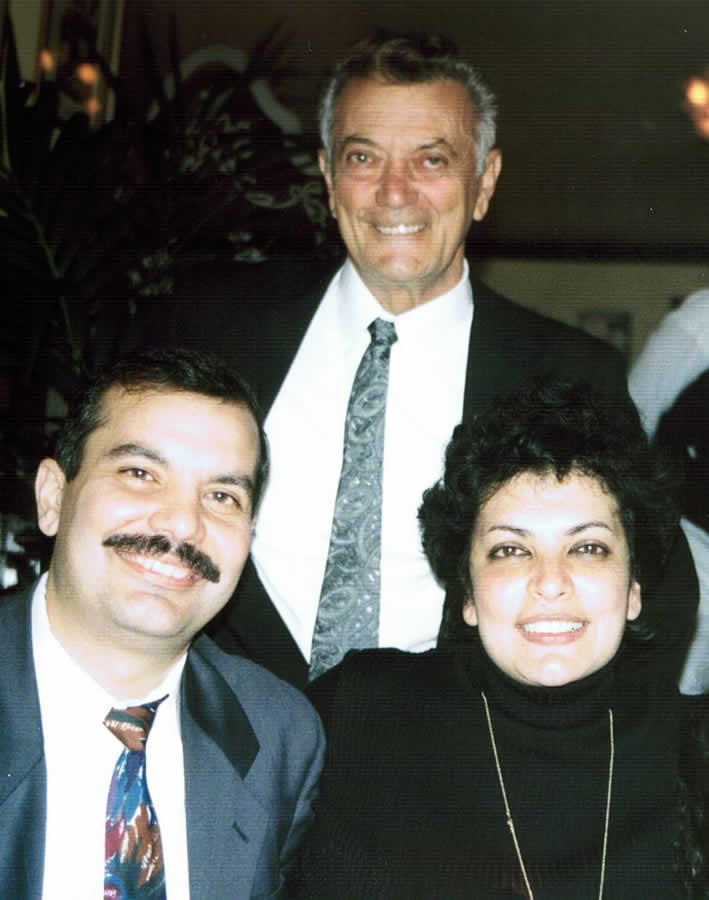

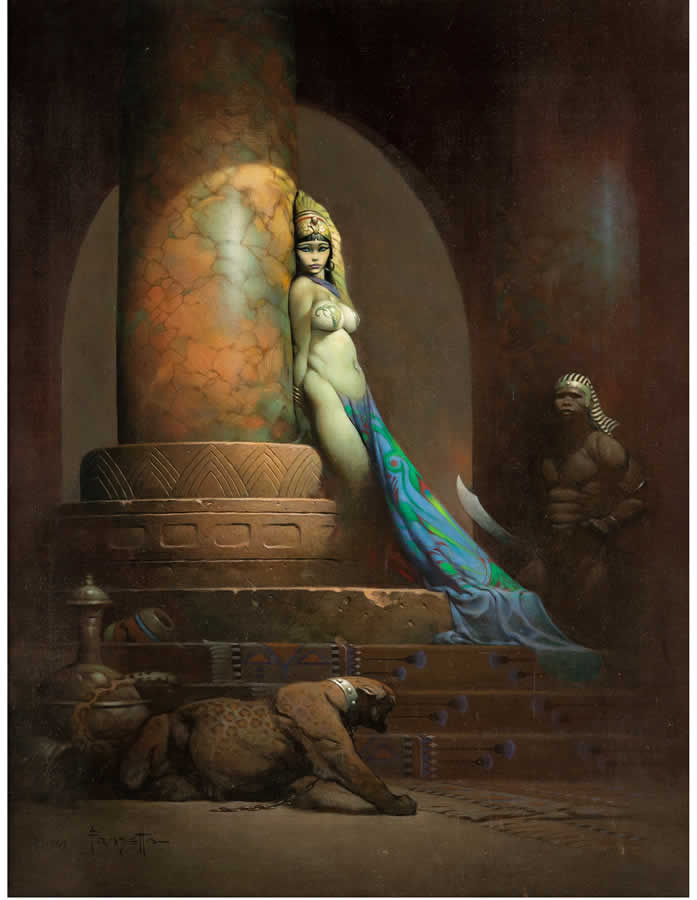

When Frazetta’s oil on canvas painting Egyptian Queen, originally produced as the cover for Eerie magazine #23 in mid-1969, sold for $5.4 million at Heritage Auctions in May 2019, it set records as the most expensive piece of original comic book art ever auctioned, as well as the top price for any painting ever sold at that auction house. If you’ve taken a good look at the Frazetta original art market, you would find the names Joe and Nadia Mannarino unavoidable. For when the Frazettas were ready to sell the originals, that is who they called.

We sat down with Joe, director of comics and comic art at Heritage Auctions in New York, to talk about this enigmatic figure and how the market finally came to meet his expectations.

Tell me about the first time you met Frank Frazetta.

I met Frank Frazetta under different circumstances several times beginning in the late ’70s. However, it was not until the late ’80s that Frank and [wife] Ellie contacted me, along with my wife, Nadia, and asked us to represent them for the sale of their original art.

Enlarge

When we went out to East Stroudsburg for this “official business meeting,” I walked into Frank’s studio and he immediately extended his hand and asked if I was “going to melt like a typical fanboy.” A bit taken back, I replied, “No, actually I am not that big a fan of your work.” He looked stunned. I went on to explain that his subject matter and the consistent bragging about completing paintings in an hour or two, while never really finishing them, seemed to be demeaning to other artists, who took their work more seriously. He asked me where I was from. I told him New York. “Where in New York?” I replied Queens. He then stated that no one in Queens can play stickball! I told him I felt I was a pretty good stickball player.

He marched me out to his backyard where he had a standard stickball/handball court setup. To my surprise, he asked if I wanted to bat or pitch first. We played two innings and we both held our own. From this point forward, he made it a goal to prove how great he really was. Of course, he quickly won me over.

How serious of a baseball player was he?

From all accounts – and I know several of his childhood friends well – he was exceptional and was actually offered a contract to play for the New York Giants. Apparently, he was unimpressed with the money and turned it down, but the sport remained a passion his entire life.

Should Frazetta’s work be considered “fine art”?

In my mind, absolutely. By any definition, he was pursuing something he loved and was uniquely gifted. He had something to say, with an unbelievably creative mind, that was inimitable. His work stirred and moved anyone that was exposed to it. He defined a genre and inspired hundreds, if not thousands, of imitators. He was considered a primary influence on two generations of upcoming artists. His images were translated into numerous mediums. Books, films and numerous licensed products were spawned from his images.

What did he want to be called? An artist or an illustrator?

A creator.

How confident was he in himself?

Supremely.

Enlarge

Was he an easy client to work with?

Never on a business level. Wonderful as friends. However, their attitude was that if anyone was willing to pay the price for a work of art, it must have been priced too low.

How was Frazetta’s creative process different than other artists you have worked with?

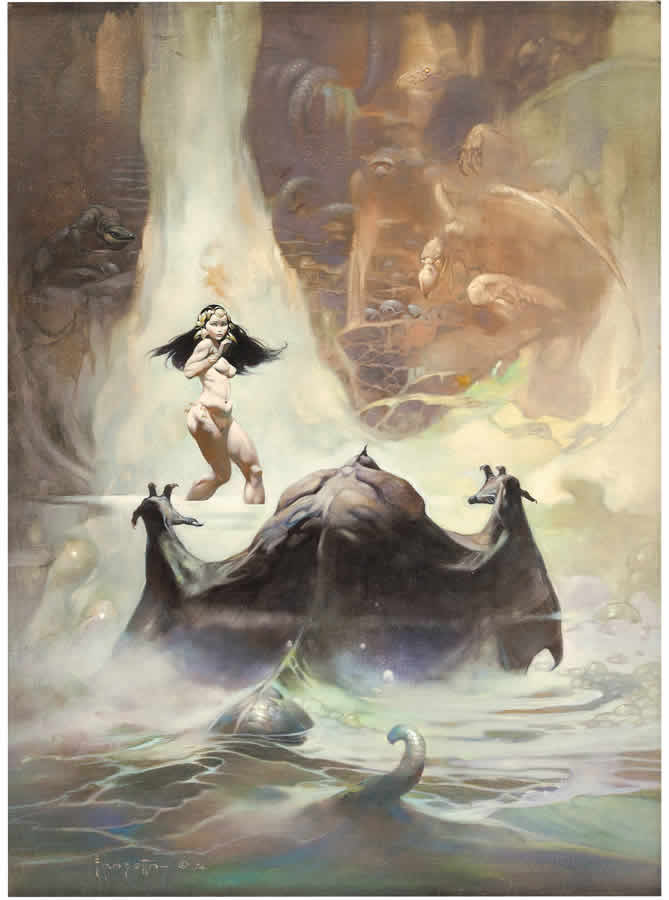

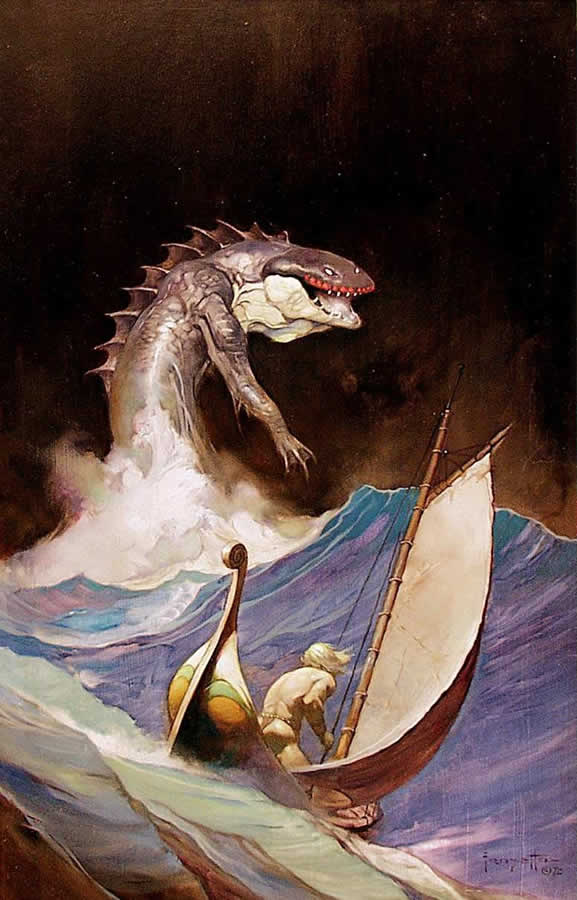

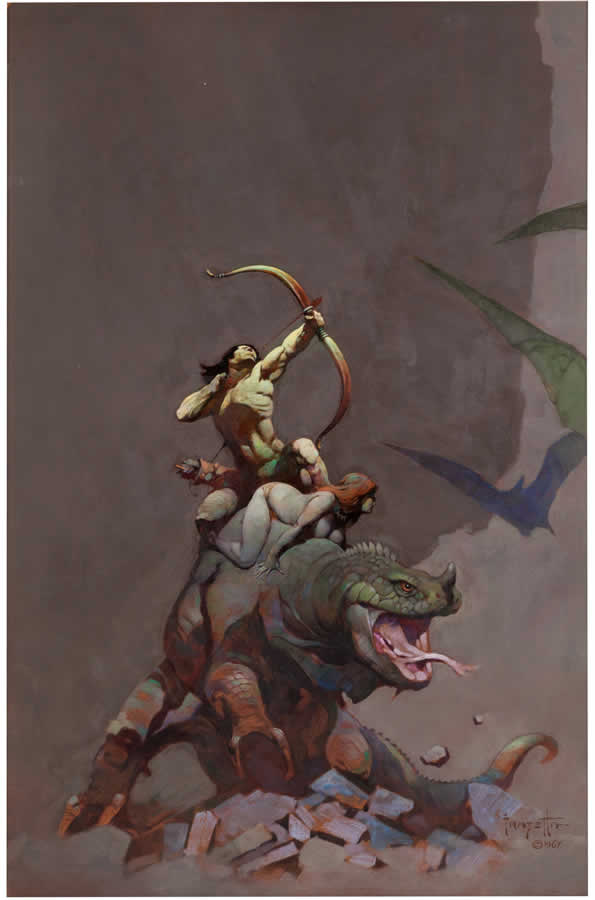

He rarely used reference material. He would develop an idea in his mind and draw a small, rough preliminary drawing usually no more than 4 by 6 or 5 by 7 inches. He would dab a few colors on the drawing, usually to determine whether to go cool or warm. As opposed to most artists, he would not create a full drawing. He would attack a canvas. Using burnt umber, he would begin from any point on the canvas and block in color. Using his fingers, he would remove paint to create highlights and expressiveness. I came to realize he painted as a sculptor, seeing in three dimensions, removing material to create a final figure or shape.

He had a unique gift where, with a few strokes, he could suggest something and it was absolutely clear what he intended.

Tell me how he approached his career of making a living by selling his art.

Frank resented being termed an “illustrator” when applied as a derogatory term, meaning one who worked on something that was directed by another. Rather, Frank felt that he could bring his sensibility to anything he worked on, making it his own. Understanding the history of art, he always resented the fact that artists needed to sell their works immediately to live. He felt that being paid for creating work allowed him to live and keep his originals.

Why didn’t he ever look for a patron?

No need. He did not want to sell his work upon completion knowing it would eventually be valued highly. He also never wanted to be beholden to anyone.

Enlarge

Was there one period when Frank’s work took off?

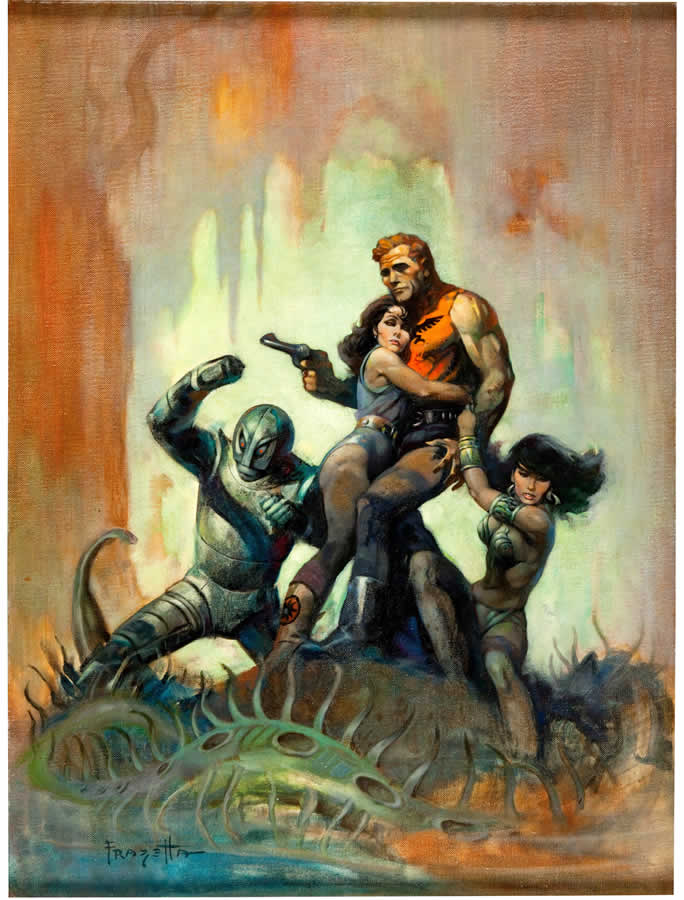

While appreciated by fans and select publishers, it was when Frank was asked to help with the covers of the Edgar Rice Burroughs novels. This was the early 1960s. This quickly led to Conan, and numerous magazine and other book covers.

Tell me about the Edgar Rice Burroughs saga.

To summarize, Edgar Rice Burroughs began writing enormously successful fiction beginning in 1912. His imaginative tales combined science fiction with adventure and captured the imagination of the country. John Carter of Mars and Tarzan engendered a franchise, appearing in virtually every known medium for the next 40 years. After a period of dormancy, the stories began to appear in paperback with covers by Roy Krenkel and Frank Frazetta. Fueled by the combination of wondrous cover art and imaginative stories, Burroughs paperbacks became a national obsession. Articles appeared in Life magazine, Time and other prominent publications. President Kennedy admitted that he was an avid Burroughs reader.

Ironically, it was Frazetta’s friend Roy Krenkel who was selected to be the chief artist of the covers for Ace Books. However, unable to make the deadlines, he turned to Frazetta, who quickly rose to dominate readers’ preferences.

Who were Frazetta’s heroes?

Frazetta appreciated a myriad of art but loved the great adventure and horror films of Hollywood’s golden age. This led to his appreciation of Hal Foster’s Tarzan. While a fan of other art, he did not like to mimic or be mimicked.

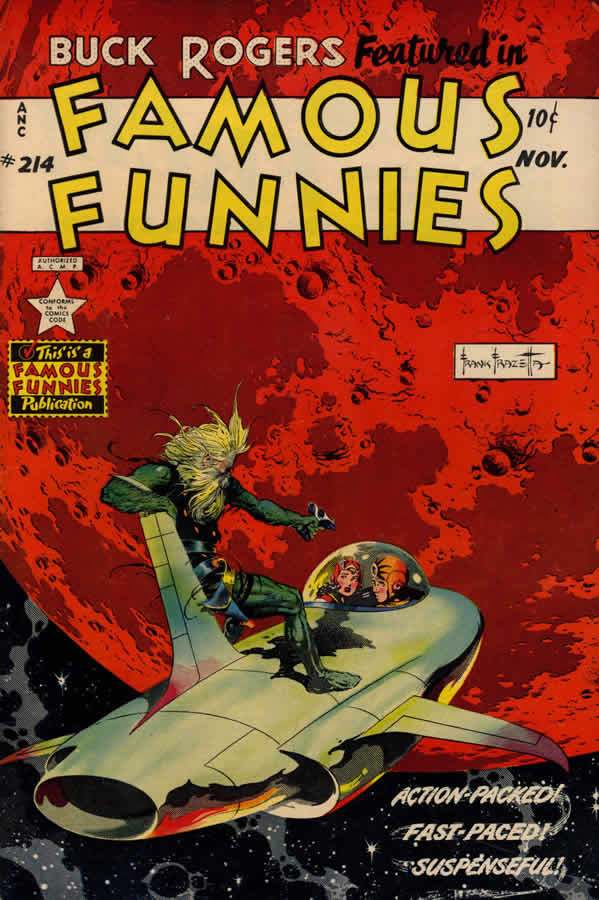

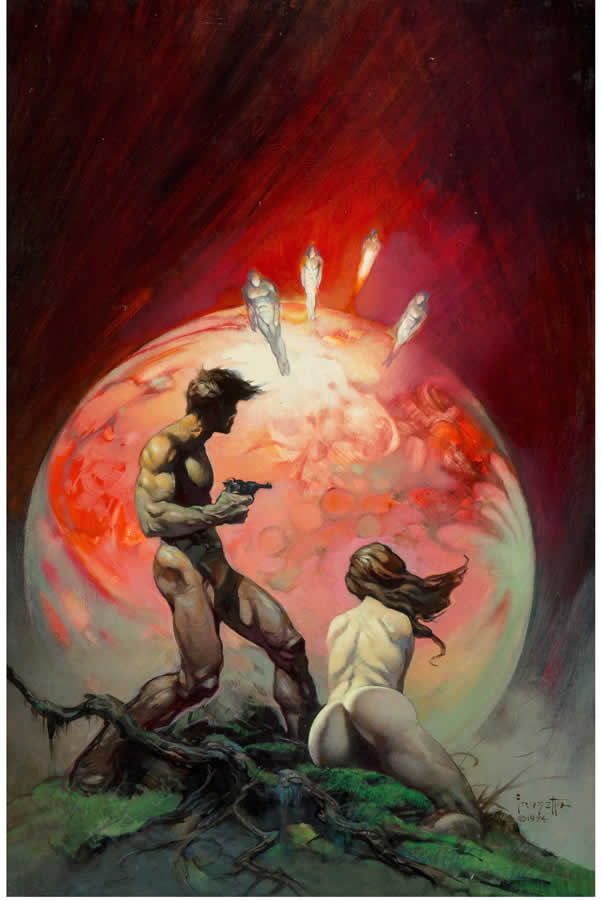

Now that the last Star Wars movie is out, is it true George Lucas’ inspiration for the Death Star came from something Frazetta painted?

Frank always told the story of a visit by George Lucas, who told him that the Buck Rogers cover of Famous Funnies #214 was an inspiration for the Death Star.

Oftentimes, illustrators create art to visualize a story, but Frazetta’s art was so good that it inspired the written word. Is that right?

Correct. Frank’s images were so compelling that magazine and book publishers would ask him to create anything he wanted and they would bring in a writer to compose a story around it. His art was ideally suited, as no one that looks at a Frazetta is not moved in some way. While we have no way of knowing total numbers, Frazetta and his family made a living selling the ubiquitous prints and limited editions that graced walls for over 50 years.

GREG SMITH is editor at Antiques and The Arts Weekly.

GREG SMITH is editor at Antiques and The Arts Weekly.

Sampling of Prices Realized

Enlarge

Enlarge

Enlarge

Enlarge

Enlarge

Enlarge

Enlarge

This article appears in the Spring/Summer 2020 edition of The Intelligent Collector magazine. Click here to subscribe to the print edition.