THE GODFATHER OF FANTASY ART HAS IGNITED GENERATIONS OF IMAGINATIONS WITH HIS SAVAGE AND SENSUAL WORKS

By Christina Rees

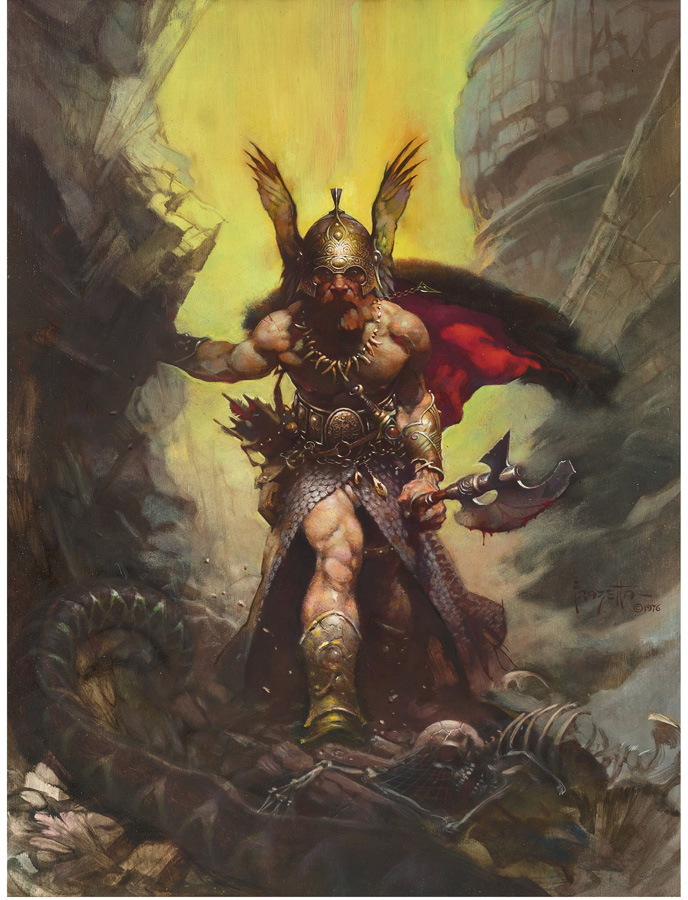

Frank Frazetta’s 1976 painting ‘Dark Kingdom’ is available in Heritage’s June 22-25 Comics & Comic Art Signature® Auction.

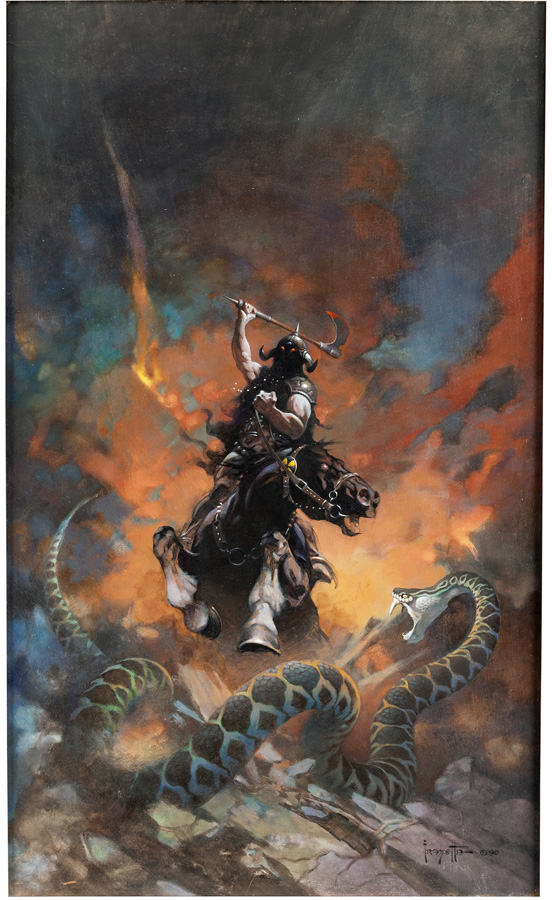

Time is a great equalizer. Just a couple of years ago on social media I posted a picture of Frank Frazetta’s Death Dealer – the most classic one, from 1973, featuring a scythe-wielding warrior on horseback. The enthusiasm for seeing such a beloved Frazetta image was immediate, and the likes poured in from artists, collectors, art critics, curators, architects, lawyers, musicians, graphic designers. But mostly artists – and some of the best I’ve personally known. Our Death Dealer lives large in the hearts of many, it seems, and we’ve certainly reached a point in time when we embrace him without question. He is family.

Nostalgia has ruled pop culture for more than 20 years now, but Frazetta is extra special. When I told one of my favorite artists, an extraordinary draftsman, that I would write about Frazetta and asked him what he thought of him, he shot back immediately: What’s not to like? He’d been admiring Frazetta’s work for years. I would guess that, spanning at least three generations, Frazetta’s creations hit a certain kind of adolescent mind like a ton of bricks, and that was that. We were imprinted. The drama! The urgency! The sex! The fantasy!

Given that Frazetta’s heyday and highest point of commercial exposure was in the mid-’60s through the early ’80s – when the world was still analog and people were still frequenting bookstores – anyone born from about 1945 to 1980 must have first encountered his book cover illustrations (though the comics readers would have seen his work far earlier) and gravitated to them whether one was into pulpy sci-fi and fantasy or not. That’s how much his work stood out. His compositions are amazing; there’s plenty of studied Rubens in there. Frazetta’s Conan and Tarzan and John Carter pictures were his most famous, and then the ubiquitous Ballantine books of his plates started rolling out in 1975. He has influenced so many artists and illustrators and comic book creators and filmmakers that if he were to be reanimated now (because that’s how it would have to be; he died in 2010) and taken to Comic-Con, the Rapture itself would break out.

I was about 7 when I guilted my dad (getting a divorce from my mom) into buying me the first Ballantine book of Frazetta’s illustrations. This was R-rated stuff for a little kid, and I certainly didn’t understand the idea of taste, or that at that time conceptual art, with its post-abstract and pop-art pedigree, made Frazetta’s images seem decidedly low and kitsch in the eyes of the art world. It is kitsch. Frazetta’s images bring to mind a scenario in which Charles M. Russell and Tom of Finland fly to Mars, form a throuple with a young Bo Derek and somehow have a kid: The Death Dealer. Or, more likely, the wide-eyed Viking holding a bloody ax while stalking a massive serpent in Frazetta’s Dark Kingdom. This image, from 1976, is as much a classic as Death Dealer, and it’s from the artist’s absolute prime canon. When I spotted the original painting at Heritage recently, I was flabbergasted.

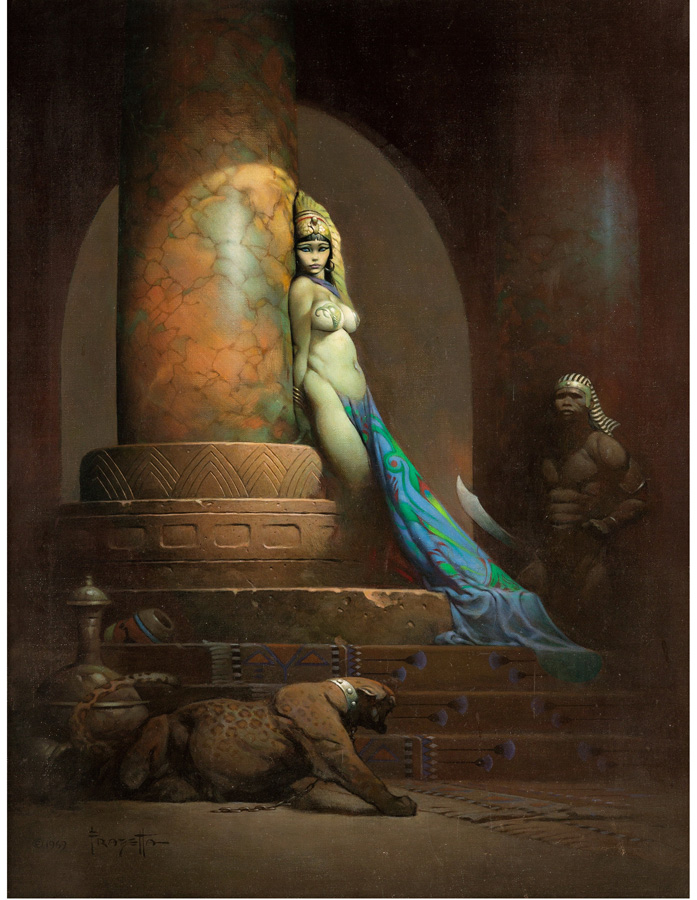

Frazetta’s ‘Egyptian Queen’ from 1969 sold for a record-setting $5,400,000 in a May 2019 Heritage auction.

Frazetta holds the auction record for original comic art, and it’s entirely possible Dark Kingdom could shatter the $5.4 million mark set by his Egyptian Queen in a 2019 Heritage auction. (The previous record was the $1.79 million paid for Frazetta’s Death Dealer 6, which was set by Heritage in May 2018.) Dark Kingdom is among his most potent works. Its image was first used as the cover of Karl Edward Wagner’s 1976 novel Dark Crusade, one in a series of tales about the immortal pre-medieval warrior Kane. But it’s far better known for its second appearance, as the album cover for Molly Hatchet’s 1979 Flirtin’ With Disaster, the Jacksonville, Florida, boogie rockers’ second record. Dark Kingdom is among Frazetta’s most reproduced works, but there is just one original, and it’s with Heritage and available to the public for the first time.

So, really: What’s not to like? The painting, which Heritage is offering in its June 22-25 Comics & Comic Art Signature® Auction, is a great reminder that Frazetta’s originals are oil on canvas, but he designed that imagery for mass reproduction. And one of the reasons fine artists can love Frazetta unconditionally is because he never attempted to cross over; he was always a commercial illustrator and never claimed to be otherwise. He understood his calling. In the 1990s, when I was in my 20s and starting to write art criticism, I don’t know what my admitted relationship to Frazetta’s work was. I had his books and knew every line and shadow of countless of his illustrations. And I assume, back then, that I never talked about it.

The artist’s 1990 ‘Death Dealer 6’ realized $1,792,500 in a May 2018 Heritage auction.

My point is that Frazetta has been a generous and lively ongoing foundation for artists for all these years, as well as for our own wider understanding of what makes for great illustration. And this is whether or not an artist’s work is in the least bit narrative or figurative, or whether or not we art lovers grow up to love conceptual art. Something has to happen to a young mind to convince it that a static image can be a massively powerful and inspiring thing – and worth trying to make. It’s no wonder art critics and curators and dealers love Frazetta, because at least a part of art appreciation springs from the idea that a creative mind can, totally from thin air, make a picture that freaks you out in the best possible way. You see it and your world has changed; your imagination has been expanded.

We grow up looking at art, and at some point we realize it doesn’t always take a ton of bricks (i.e., roiling Viking muscle, spurting blood, perfect teardrop tits) to have this effect. We move, in our education, from broad to finer to fine. We grow up and are impacted by a painting, a photograph, a drawing, a digital image whose subtlety certainly escapes the appreciation of a 7-year-old. I’m not implying that Frazetta functions only as a setup for high art appreciation. His work still has the power to make one feel (immediately, without reflection) tense, aroused, dazed, amused, grief-stricken.

Time is the great equalizer, but with Frazetta’s work, time didn’t have to stretch far to convince us of his greatness. We loved him once upon a time and find it all too easy to love him all over again.

A version of this article originally appeared in Glasstire.

CHRISTINA REES is a staff writer at Intelligent Collector.

CHRISTINA REES is a staff writer at Intelligent Collector.