FROM SACRIFICE TO TRIUMPH, THESE PERSONAL LETTERS AND ONE REMARKABLE BROADSIDE CAPTURE THE MOMENTS AND EMOTIONS SURROUNDING A REVOLUTION

By Sandra Palomino | July 1, 2025

As the Fourth of July approaches, commemorating the birth of American independence, a selection of Revolutionary War-era manuscripts offered in Heritage’s August 8 Historical Manuscripts Signature® Auction narrate the arc of a nation’s founding struggle. From the days leading up to the war’s first shots to the moment that brought an end to the yearslong conflict, the four remarkable manuscripts featured below span uncertainty, resilience and ultimate triumph.

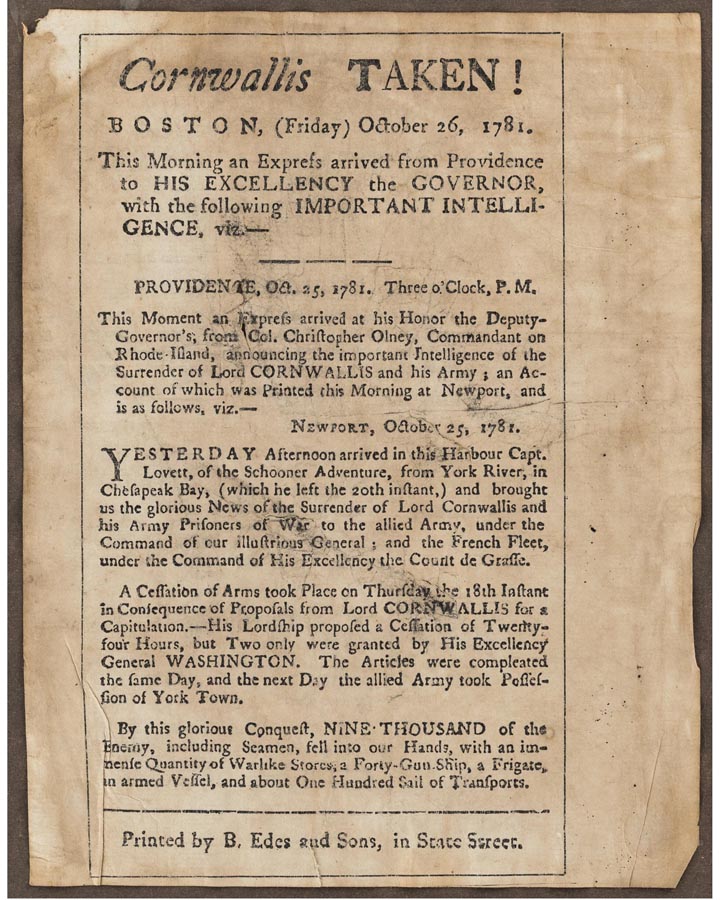

A newly discovered broadside announcing General Charles Cornwallis’ surrender at Yorktown, Virigina, in October 1781 proclaims the climactic victory that effectively ended the war. Printed in Boston by Benjamin Edes and Sons on October 26, just two days after the arrival of the emissary bringing the news, it celebrated the capture of over 9,000 British troops and vessels by the combined American and French forces under General George Washington and Admiral François Joseph Paul de Grasse. This pivotal moment confirmed the success of the colonies’ fight for freedom – news met with public jubilation and immortalized as a victory for self-government.

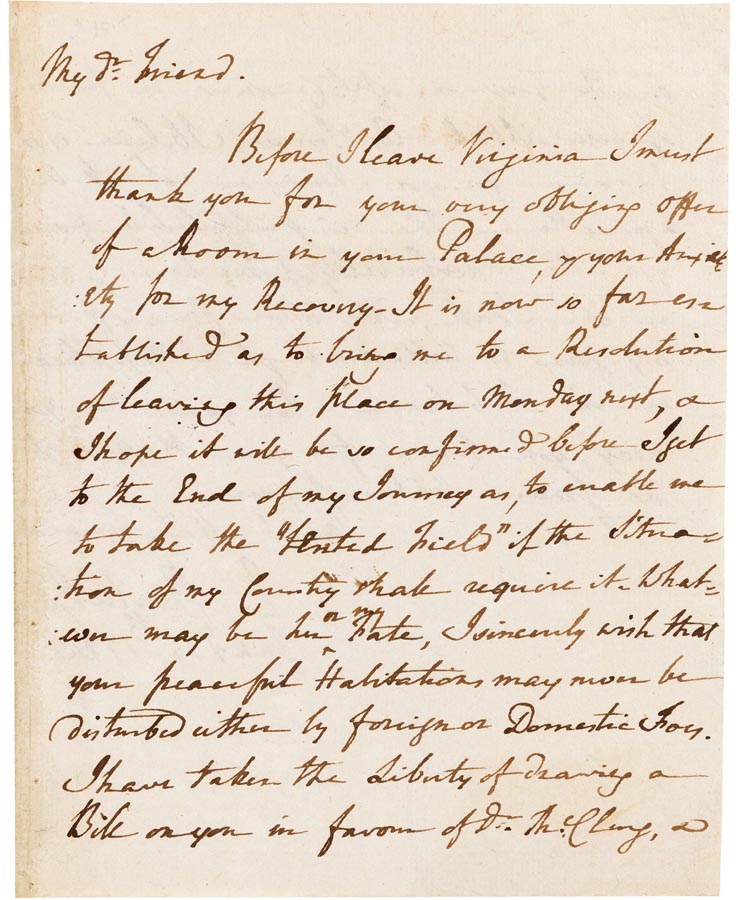

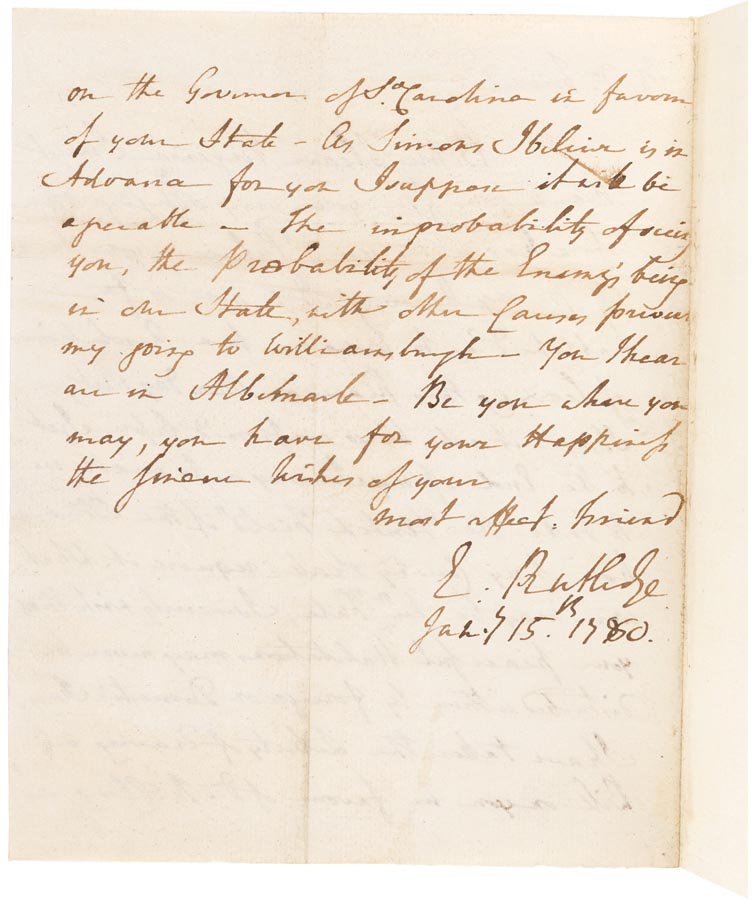

But behind the triumph lay hardship and upheaval. Writing from Virginia on January 15, 1780, founding father and Declaration of Independence signer Edward Rutledge of South Carolina notifies the recipient (possibly Thomas Jefferson, who was then serving as governor of Virginia) that he is ready to “take the tented field” if his country required it and of his impending return to Charleston. Rutledge had fought at the Battle of Port Royal in February 1779, and although there is no record of his having been wounded, he was offered the Governor’s Palace in Virginia for his recovery and was cared for by noted doctor James McClurg. Rutledge returned to Charleston and was imprisoned four months later during the British capture of the city. His letter, penned with civility and duty, reflects both the personal cost of war and the courage of those who held the republic’s fate in trust.

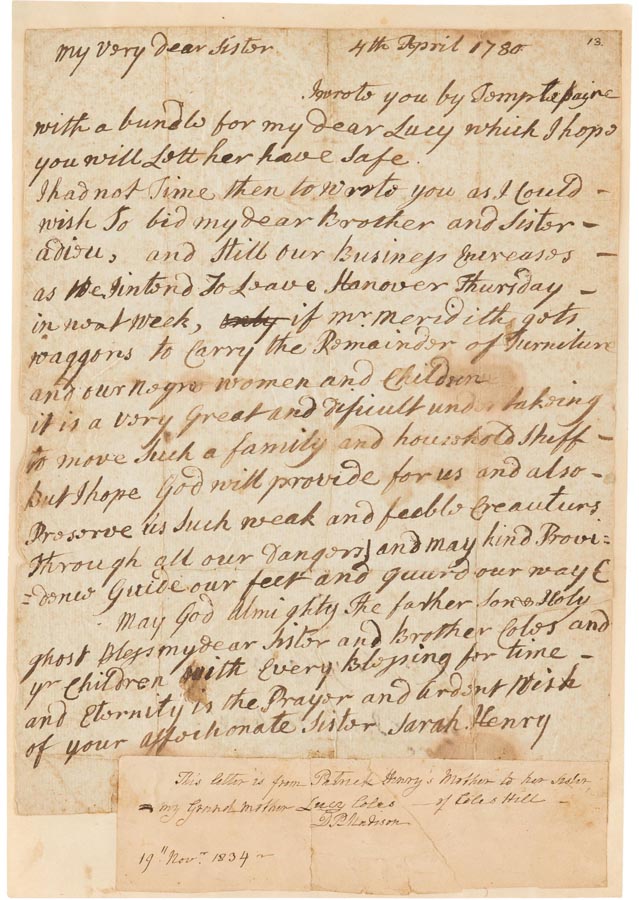

Meanwhile, on April 4, 1780, Sarah Henry, mother of patriot Patrick Henry, wrote to her sister (Dolley Madison’s grandmother, Lucy Coles) about the family’s frantic effort to flee Hanover County, Virginia. With wagons needed for “negro women and children” and “household stuff,” her words capture the war’s toll on civilian life and the enormous burden carried by Southern families – especially enslaved people – amid the disarray of advancing British forces.

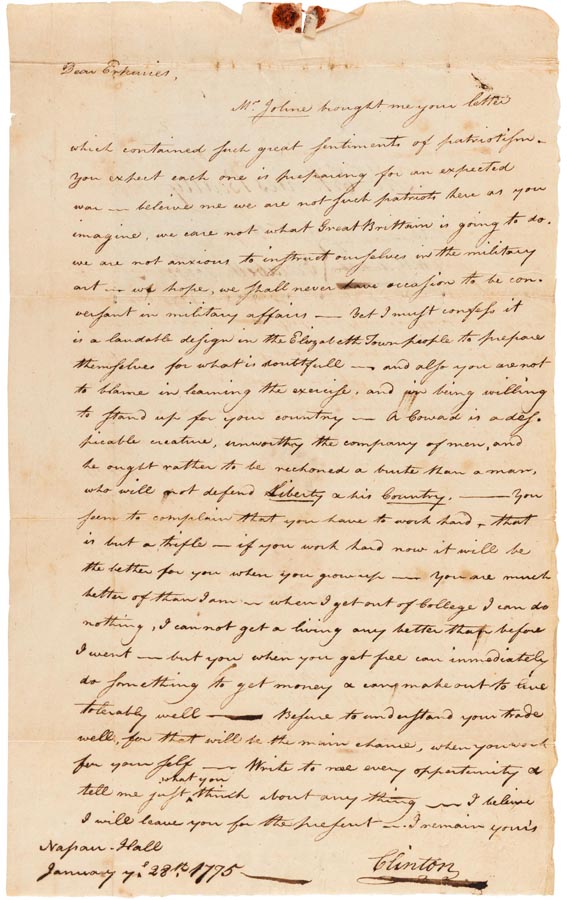

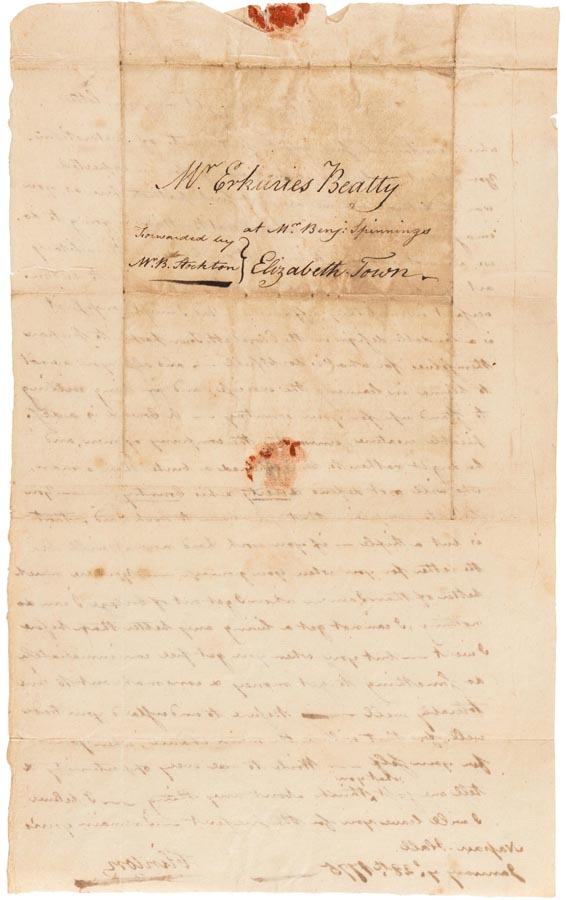

Finally, a brother’s warning from New Jersey in January 1775, just months before the first shots of the war were fired at Lexington, reveals a divided yet awakening populace. “We care not what Great Britain is going to do,” writes Charles Clinton Beatty, a senior at the College of New Jersey (now Princeton University). He acknowledges the “laudable design” of those preparing for war and adds: “A coward is a despicable creature, unworthy the company of men, and he ought rather to be reckoned a brute than a man, who will not defend liberty & his Country.” Beatty enlisted into the Fourth Pennsylvania Battalion as a second lieutenant in January 1776 but was killed a few months later when a fellow soldier accidentally discharged his firearm.

Together, these four voices echo the American Revolution’s essence – sacrifice, conviction and the unyielding pursuit of independence, ideals that endure each Fourth of July.