A NEW BOOK EXPLORES THE ARTIST’S PERSONAL AND PROFESSIONAL FASCINATION WITH THE SUBJECT HE CALLED ‘A SCULPTURE OF MANY PARTS’

By Andrew Nodell | October 7, 2025

For more than half a century, Man Ray (1890-1976) explored the theme of chess in his works of art, encompassing photography, painting, abstraction, and – most prolifically – in his design and production of playable chess sets. For the past two decades, Larry List has drawn on his experience as an author, artist, curator, and researcher to explore Man Ray’s career-long obsession with this centuries-old game of strategy, culminating in the recently released Permanent Attraction: Man Ray & Chess, a 265-page book featuring more than 300 illustrations.

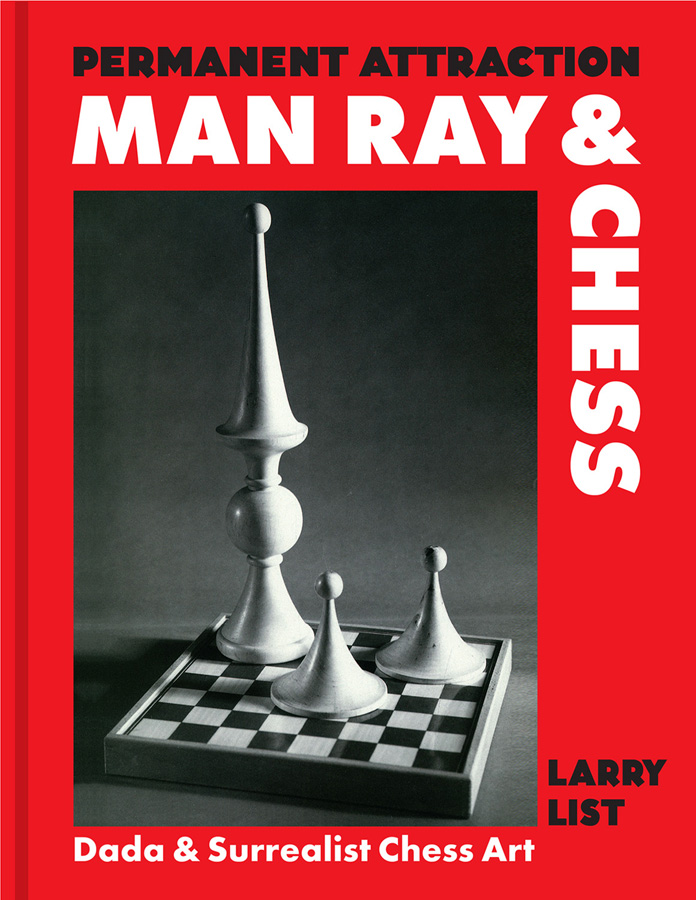

‘Permanent Attraction: Man Ray & Chess.’ 2025. 10 x 8 in. 265 pages. 350 images. Published by Hirmer/Verlag. Distributed by Thames & Hudson and University of Chicago Press.

Man Ray’s chess-related art was a “telling form of cultural portraiture of the artist and his era,” List says, and included the Modernist influence of Art Deco and Nouveau, peppered by the “contrarian nature of Dada and the fevered dreams of Surrealism.” The artist relied on his masterful draftsmanship skills to create innovative and often eccentric designs, which were produced by a diverse range of talented artisans and craftsmen, including cabinetmakers, wartime machinists, and luxury jewelers. While Man Ray’s interest in photography, portraiture, and painting waxed and waned over the course of his career, List contends that chess stands as a lifelong theme in his work, which is also being explored in the exhibition Man Ray: When Objects Dream, on view at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art through February 1, 2026.

We recently sat down with List to discuss Man Ray, chess, and Permanent Attraction. Keep reading for highlights from our conversation.

MAN RAY. 1920 Wood Chess Pieces. Clear hardwood. Natural and painted opaque black finishes. Tallest piece 3¼ in. (8.3 cm). Referred to by the Metropolitan as Chessmen 1920–24. Gustavus Pheiffer Fund, 1971. #1971.18 1a–p, aa–pp. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. LL. © 2025 Man Ray 2015 Trust/Artists Rights Society/ARS, New York/ADAGP Paris.

INTELLIGENT COLLECTOR: In your research, what did you discover about Man Ray’s early practice?

LARRY LIST: Over the years, I had examined many of Man Ray’s works, and I had always wondered about his first chess set, from 1920, because the forms were so perfectly executed. Man Ray was a trained draftsman, a talented painter and photographer, but the one skill set he didn’t have was woodworking. Nor did he have access to a wood shop. He didn’t know how to operate a lathe, a milling machine, or a table saw. And those first forms were so perfect, I thought he had to have gotten them from some other source. And in 1920, when he made that set, he was poor, so he wouldn’t have had the money to go to a professional woodworker and have them custom-made.

He was trained at Boys’ High School [in Brooklyn] to do mechanical drawing, but there were no drawings for that early set. He drew perfectly accurate drawings for his chess sets both before and after that. The ones he produced in the 1940s, 1950s, 1960s, and beyond were created from perfectly accurate, squeaky-clean mechanical drawings. I discovered that in the early 20th century, the public schools and art schools all used education kits of little wooden geometric forms to help teach drawing and geometry. They were sold by companies that produced educational books and supplies, and like wooden mannequins that are still available in art stores today, they were cheap and widely available. Man Ray and Marcel Duchamp were exploring the art of the Readymade and found object assemblage, so it made sense that Man Ray simply bought enough of these cheap kits to get all the cones, cubes, spheres, etc., to create a complete chess set. It took me years to track down examples of these kits, but that’s how I finally figured out that’s what he did to create his first chess set.

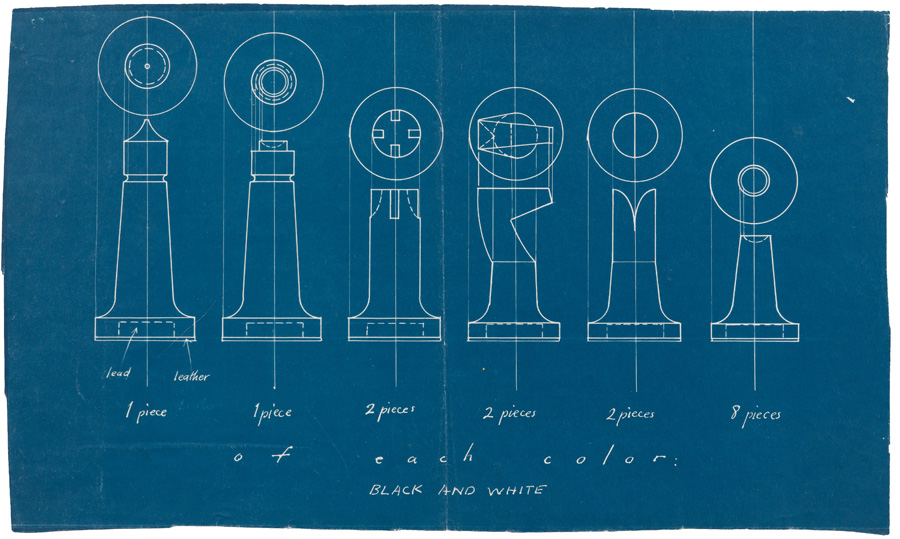

MAN RAY. ‘Blueprint for Chess Pieces.’ Blueprint/cyanotype on commercial Blueprint paper. 9¼ x 15½ in. (23.5 x 39.37 cm). MRT#21713.17. Maruani Mercier, Brussels. © 2025 Man Ray Trust/Artists Rights Society/ARS, New York/ADAGP Paris.

IC: What struck you about Man Ray’s mechanical drawings as they relate to his chess sets?

LL: I am seriously in love with his mechanical drawings. They’re like the 20th-century version of Leonardo da Vinci’s sketchbook drawings of fantastic machines and devices. And with that ability, which none of the other Surrealists or practically none of the other artists of his era possessed, he was able to eventually create these mechanical drawings, which reflected the machine age on the one hand, but were also used to produce perfectly accurate editions or custom, unique commission pieces. It was something that he was able to interject into the fine art world before anybody else. He replaced academic drawing with mechanical drawing, and he replaced classical academic art-making techniques with commercial processes and methods.

IC: In what ways was Man Ray’s artistic practice shaped by the times in which he lived?

LL: He was certainly shaped by his times and his upbringing. He was blessed in that he wasn’t old enough to serve in World War I and that he was too old to serve in World War II. Because he was too poor to afford to hire someone to photograph his artwork, he had taught himself photography. Once he was in Paris, he became the artwork photographer of everybody from Picasso on down. They then recommended him to the fashion houses. He also took photo portraits of his artist friends, which Sylvia Beach displayed in her fashionable bookstore, Shakespeare and Company. This led the wealthy leisure class in Paris to seek having their portraits done by Man Ray. His lucrative fashion and portrait photography supported his experimental work as a Dada and Surrealist artist. He was so successful with his commercial work that he had to rent a separate private studio just for doing his painting.

When he was driven out of Paris and back to America in 1940 to escape the Nazis, he had to leave behind the career he’d built over almost 20 years. He had a beautiful girlfriend, Ady Fidelin; he had a lucrative commercial photo career; and he had a reputation as an avant-garde artist. At age 50, he had to leave all of that behind. He arrived back in New York, which had become a hotbed of other expatriate artists competing with young, ambitious New York artists. And so, being such a contrarian, he hitched a ride cross-country with a necktie salesman and ended up staying in Los Angeles for a decade. He initially liked Los Angeles because it reminded him of the south of France, with its sunny days, palm trees, and beautiful people with suntans. Many of those beautiful celebrities bought his chess sets, but practically nobody bought his photographs, and practically nobody bought his paintings.

MAN RAY. ‘The Knight’s Tour.’ Inspired by a challenging classic chess problem of the same name. Oil on board. 1946. 13½ x 13½ in. (35.5 x 35.5 cm). Framed: 19½ x 19½ in. (49.5 x 49.5 cm). Bought by his former photo assistant and paramour Lee Miller after she became the wife of British painter and art historian Sir Roland Penrose. The Penrose Collection. East Sussex, England. © 2025 Man Ray 2015 Trust/Artists Rights Society/ARS, New York/ADAGP Paris.

IC: Was Man Ray commercially successful with his chess sets during his lifetime?

LL: He tried to identify himself solely as a painter in Los Angeles [from 1940 and beyond]. He turned down commercial photo projects and didn’t do much experimental photography. He ran through all the money he’d saved from his commercial photo career, so to start earning again, he began selling chess sets. It provided him with a little money, but not enough.

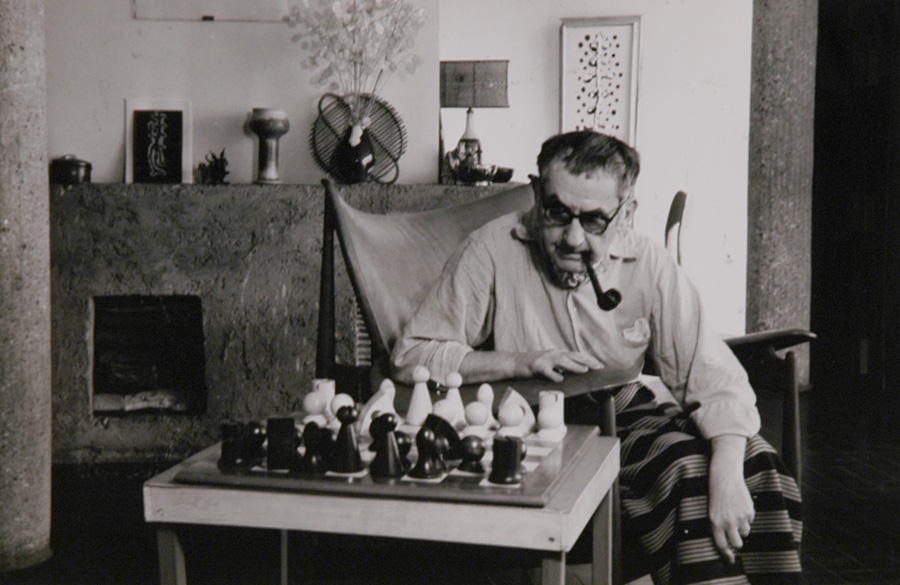

IC: How did the design of Man Ray’s chess sets evolve throughout his career?

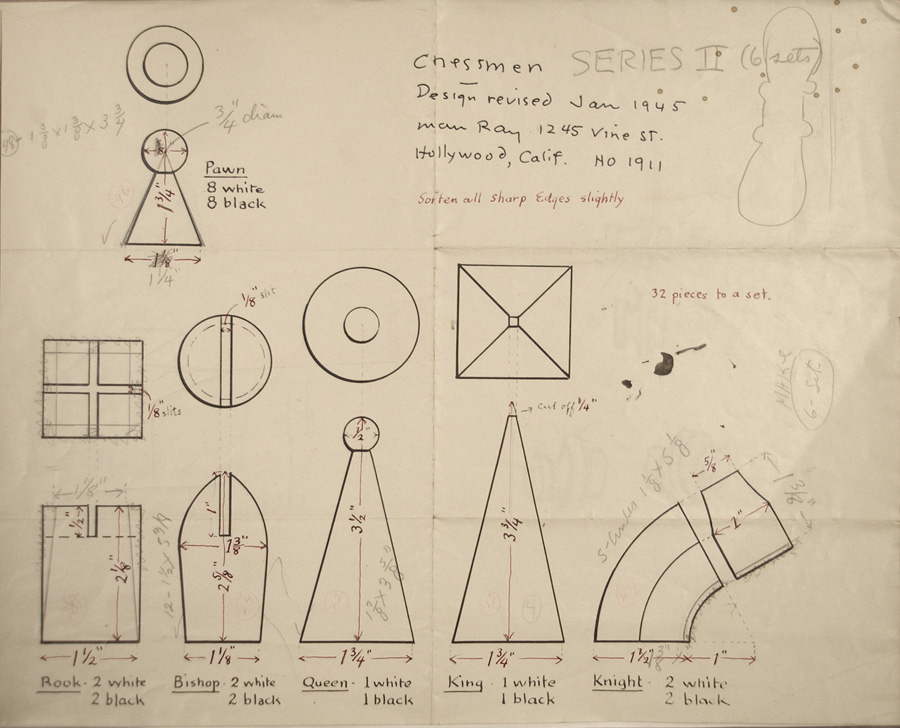

LL: If you examine the shapes he created, you’ll realize, for instance, that the reason he added a small knob at the top [of the king or queen] was to make it easier to grip. Over time, he continued to develop the pieces, finding ways to make them more pleasurable and secure to hold with your fingers. He was very aware of that. He had an original geometric vocabulary to start with, but he constantly redesigned and refined the pieces throughout his lifetime. I know he redesigned the knight pieces at least nine times.

MAN RAY. ‘Man Ray with 1964 Ivory Chess Set.’ Gelatin silver print. c. 1964. Silver gelatin print. 5 x 7 in. (12.7 x 17.8 cm). Man Ray Trust. © 2025 Man Ray 2015 Trust/Artists Rights Society/ARS, New York/ADAGP Paris.

IC: In what ways did Man Ray’s move to Los Angeles directly influence the design of these war-era chess sets?

LL: Wartime proved to be an opportune time for Man Ray to make chess sets in Southern California because there were major ship and aircraft fabricators for the Navy and Army Air Corps who attracted many highly skilled machinists. All of the best-quality materials, including fine hardwoods, aluminum, and steel, were strategic materials, and therefore, they were scarce. But Man Ray realized that the cutoffs and mill ends of these materials might be too small to be usable for airplane or boat parts yet big enough to make a few chess pieces from. As we’d mentioned, he’d been trained to make precise mechanical drawings from which these machinists could easily make accurate editions.

His first wooden chess sets were fine, large sets produced in small editions. However, they didn’t sell as well in California as he had imagined they would have in Europe, where people traditionally played chess sitting quietly in their homes or at chess clubs. But in LA, people were more mobile. They’d throw stuff in a picnic basket, get in the car, and roll on out to spend the day at the beach. It was a loose and lively “Let’s play chess on the patio, daddy-o” attitude.

Building boats and planes consumed huge amounts of aluminum, so Man Ray began using cutoff pieces of aluminum to make light, bright, and portable, smaller-scale sets. Traditionally, chess sets had always been black and natural wood, or black and ivory or very muted colors. However, the most permanent way to color aluminum was to anodize it, which opened up a whole broad new Technicolor world of color combinations that hadn’t been seen before. Of course, there had been chess sets available in a limited variety of colors, but you certainly didn’t see fluorescent orange and yellow ones. He made these sets small, so they were portable, but because they were solid metal, they had weight that communicated “Oh, I’m handling something of value.”

IC: Why were Man Ray’s chess sets so popular in Los Angeles?

LL: Through his friend, the film producer Albert Lewin, Man Ray met the Hollywood Chess Club, which was formed by chess master Herman Steiner and comprised of professional actors, including Jose Ferrer, Vincent Price, Charles Boyer, Lauren Bacall, Spencer Tracy, and others who played chess between takes during the filming of the movies. Humphrey Bogart even served as the chairman of the National Chess Federation for the state of California, all while being the highest-paid male actor in the world at the time. So, the interest was intense and very broad.

IC: Have there been any significant sales of Man Ray chess sets in recent years?

LL: When David Bowie’s estate came up for auction in 2016, I was contacted by an art consultant who acquired art for a family with a child interested in chess. The consultant noticed a Man Ray chess set in this sale. This particular set was part of a 1945 edition of six, with the only other known copy belonging to the Philadelphia Museum of Art. I traced the edition number and found that the set being offered was originally a gift from Man Ray to his gallerist, Julien Levy, who had introduced Surrealism to America. David Bowie purchased the set from the Levy estate auction.

MAN RAY. ‘Chessmen (Series II).’ January 1945. (The design drawing for the David Bowie Chess Set.) Red and black ink and pencil on Photostat paper. 11 x 14 in. (28 x 35.5 cm). #21713.38. Man Ray Trust. LL. © 2025 Man Ray 2015 Trust/Artists Rights Society/ARS, New York/ADAGP Paris.

MAN RAY. ‘1945 Wood Chess Pieces (Series II).’ Natural and ebonized birch hardwood. Tallest piece: 3 1/2 in. Signed in ink, dated and numbered on bottom of white King ‘The King—Series II Set No. 3.’ From edition of six. Gift from John F. Harbeson. 1964. Accession #1964-91-36(1-32) Philadelphia Museum of Art. LL. © 2025 Man Ray 2015 Trust/Artists Rights Society/ARS, New York/ADAGP Paris.

It was a beautiful design, in very fine condition, and had a provenance that was singular in terms of art history and popular culture, which possibly set it apart from other examples. At that time, a nice 1940s wooden Man Ray chess set was maybe $40,000, tops. However, on the day of the auction, there were two people in the room who both wanted it. I got a phone call later from my friend, who excitedly declared, “We got it! We got it!” for over $130,000 plus fees.

IC: What do you hope readers take away from your exploration of Man Ray’s relationship to chess?

LL: Well, that chess wasn’t tangential, but was a lifelong theme in Man Ray’s work. It is a longer “through line” than any other one that I’ve found in terms of tracking Man Ray’s development as an artist from the time he was in high school to the time he died. However, the takeaway for me is that through his chess-related work, Man Ray pioneered the introduction of many commercial processes and materials into the fine arts. Interestingly, Andy Warhol later adopted Man Ray’s practice of supporting his experimental art and film projects by doing lucrative portrait work and fashion photography. Warhol, too, then introduced commercial photo silk screening as a fine art painting process.

Author Larry List with pieces of the replica set of the ‘Man Ray 1920 Wood Chess Set’ by AMEICO. Photo: Kathy Grove.

IC: What advice would you offer to those considering collecting Man Ray’s chess sets?

LL: I would encourage potential collectors to re-examine Man Ray’s chess sets as the artist regarded them – as “a sculpture of many parts.” They are exquisite tabletop sculptural ensembles. They are the only artworks made to be handled and enjoyed. For example, a set belonging to [jazz musician] Artie Shaw has what is called “honest wear” because it was actually played with and traveled with the musician. Others were kept in their little cases and are pristine. In a few cases, it is still possible to acquire the design drawing for a set, the wood prototype for that set, and a copy of the finished edition so that you can follow the artist’s creative process the entire way from inception to prototype to completed final work.

It is my hope that the book will serve as an interesting introduction to this new body of Man Ray’s work and a guide for collectors, curators, and chess aficionados who wish to investigate this vast array of chess-related material by the artist.

All works by Man Ray © 2025 Man Ray 2015 Trust/Artists Rights Society/ARS, New York/ADAGP Paris. Header image: MAN RAY. 1946 Aluminum Chess Set. Yellow and orange anodized lathe-turned aluminum with black felt bottoms. Tallest Piece: 2 x 1 x 1 in. (5.1 x 2.5 x 2.5 cm). Edition # 11/12 Incised on Orange King ‘Man Ray, 1926–1946, The King, 11/12.’ Heritage Auctions, Dallas and New York. © 2025 Man Ray 2015 Trust/Artists Rights Society/ARS, New York/ADAGP Paris.