FAMED KIOWA WARRIOR’S 1876 DRAWINGS OF CAPTIVITY REPRESENT HIS EARLIEST-KNOWN WORK

By Mike Cowdrey

The so-called Red River War raged across North Texas and the Indian Territory during 1874-75, when the Comanche, Kiowa and Southern Cheyenne tried to drive out hordes of white buffalo hunters who had invaded their homeland in violation of treaties, and were destroying the livelihood of the Southern Plains tribes.

EVENT

ETHNOGRAPHIC ART SIGNATURE® AUCTION 5361

June 26, 2018

Live: Dallas

Online: HA.com/5361a

INQUIRIES

Delia E. Sullivan

214.409.1343

DeliaS@HA.com

U.S. Army units sent to protect the invading hunters fought a series of battles, eventually trapping the tribes at their winter encampments in Palo Duro Canyon in the Texas Panhandle, destroying several villages and most of their winter supplies of food. This forced the starving survivors to walk to Fort Sill in the Indian Territory and surrender.

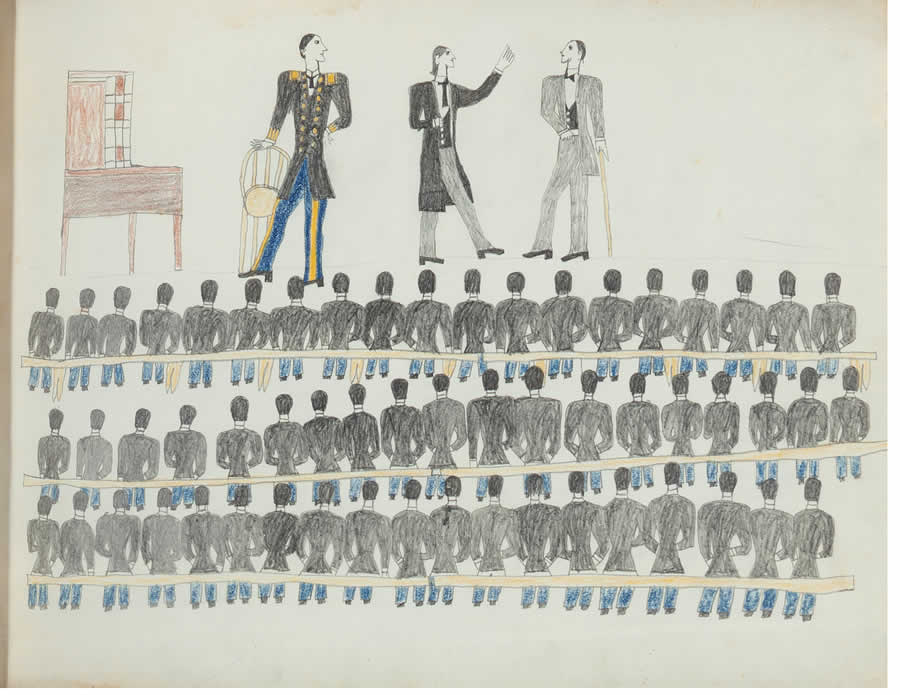

Fearing a quick renewal of hostilities, the Army adopted a strategy of taking hostages to guarantee the “good behavior” of the tribes. In spring 1875, 71 Southern Plains Indian men in manacles and chains, and two women and one child were transported from Indian Territory more than 1,000 miles east to a three-year imprisonment at Fort Marion in the Atlantic town of St. Augustine, Fla. The long journey was made by wagon, steamboat and train. Among these prisoners were 27 Kiowa men, according to Capt. Richard H. Pratt’s memoir, Battlefield and Classroom. One of the youngest, only 19, was named Hunting Boy (Etahdleuh Doanmoe).

Shortly after arrival in Florida, Pratt, who was in command at Fort Marion, discovered that many of the men were avid artists long used to recording experiences of their lives on the pages of account ledgers, an extension of traditional paintings done on buffalo robes. Scrambling among the businesses of St. Augustine, and later with the assistance of supporters throughout the eastern United States, Pratt was able to locate sufficient sources of paper, pencils, ink, crayons and watercolors to keep many of his charges occupied.

St. Augustine had long been a tourist town, where wealthy Americans from New England and the Midwest could escape the northern winters. On weekends, civilians were allowed to visit the prison. Very quickly it developed that not only were many of these men accomplished artists, but many of the visitors admired their work and were willing to pay good money for it. Pratt saw a source of income and hope for men who had little of either. He presented collections of Indian drawings to prominent visitors who thereafter became supporters and contributors to his program of rehabilitation for men who had been indicted – many felt unfairly so – as war criminals.

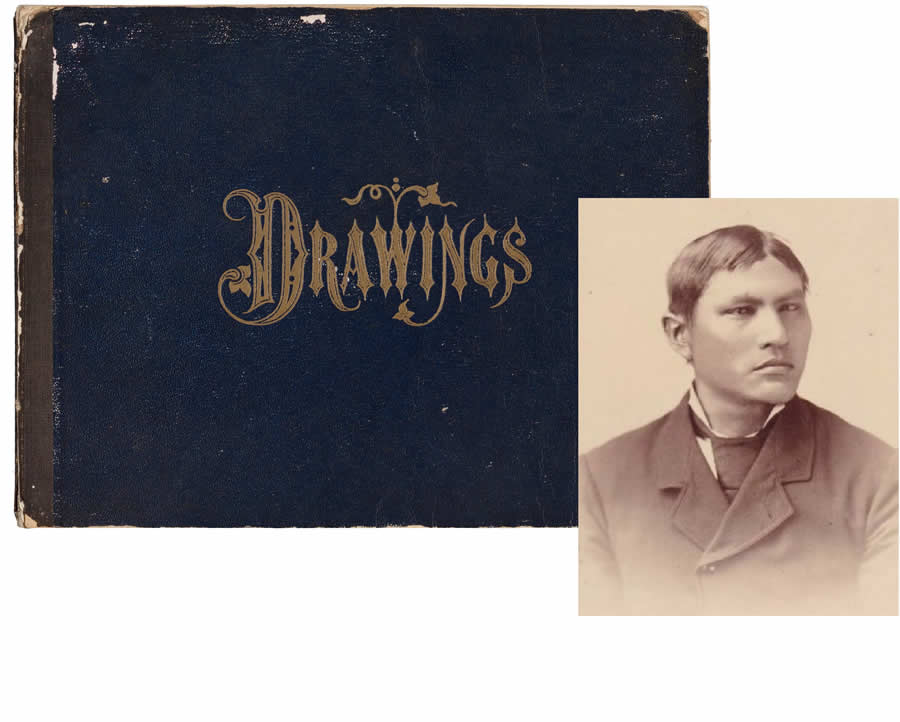

One of these wealthy supporters was Sophia Negley, a pillar of the Presbyterian community at Pittsburgh, Pa. During a visit the following year, she acquired a collection of 33 stunning compositions, inscribed “Book of drawings by Etahdleuh Kiowa prisoner Fort Marion St. Augustine, Fla Aug 1876.” The date is significant. Front-page news across the United States the previous month, while the 20-year-old Kiowa artist was creating this record, reported the “Custer Massacre” in far-off Montana Territory.

Enlarge

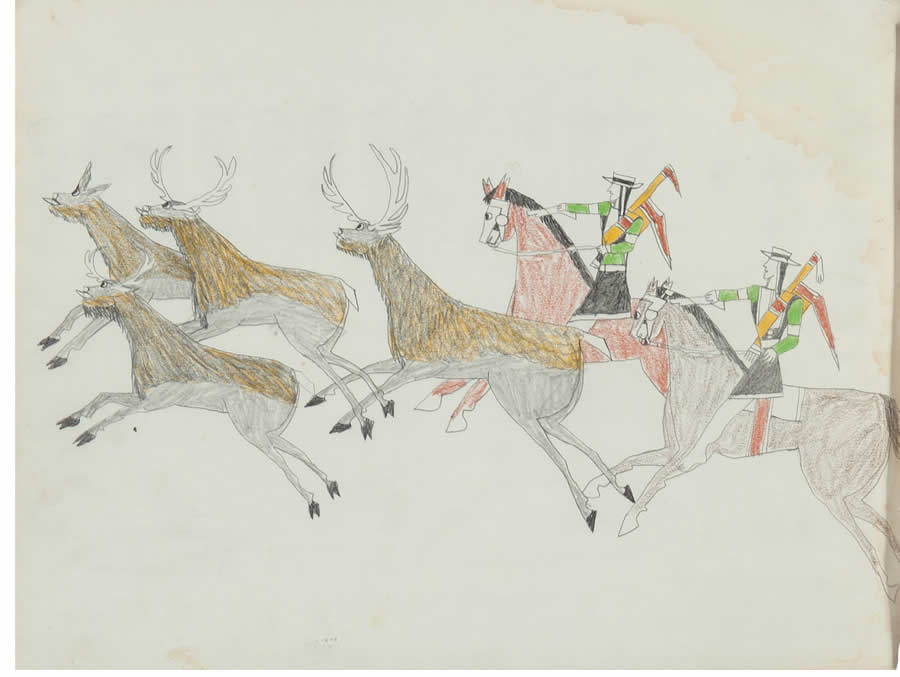

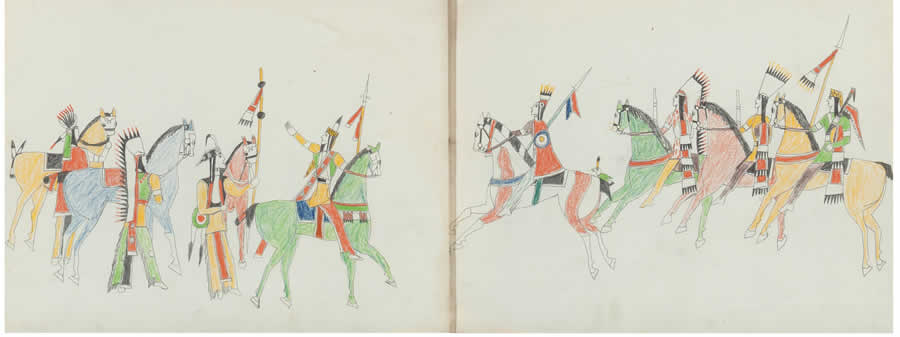

Other drawings by Etahdleuh grace the collections of the National Anthropological Archives, the Beinecke Library, Yale University and elsewhere, but this book collected in 1876 is his earliest-known work, hidden from all but the Negley family for the past 142 years. Compositions include hunting scenes for buffalo, elk, white-tailed deer, turkeys and golden eagles; his honorable service as a hunter locating buffalo to feed his people, and as a scout for war parties; or parading in his “best dress” to show off for the girls. A two-page, large-scale battle scene against Sac & Fox hunters must depict a deed by Etahdleuh’s father, since this famous conflict occurred in July 1854, shortly before the artist was born. A bird’s-eye view of Fort Sill, with surrounding streams and nearby Medicine Bluff, documents the spot from which he was launched, in chains, into a different world. Four drawings show the prisoners’ life at Fort Marion.

After three years, when war on the Southern Plains was over, most of the prisoners were allowed to return to Indian Territory. Etahdleuh volunteered to remain in the east. He spent 1878 attending the Hampton Institute in Virginia, polishing his knowledge of English. In 1879, he was among the first class of students at the new Indian Industrial School in Carlisle, Pa. In 1882, Etahdleuh’s married another Kiowa student, Laura Tone-adle-mah (Broken Leg), sister of the last Kiowa head chief. The couple would have two children.

Enlarge

The Presbyterian congregation at Carlisle had long supported and encouraged Etahdleuh’s and Laura. In gratitude, Etahdleuh’s studied for and was ordained as a minister of that faith. In autumn 1887, the couple returned to Indian Territory, at Anadarko, as teachers. Etahdleuh’s wrote to Pratt in February 1888: “I will do all I can for the good of my people.” What he did not communicate was that he was wasting away from tuberculosis. Three months later, the school’s newspaper, The Indian Helper, reported:

“Sadness came to the hearts of all our students and employees who gathered in the chapel Saturday evening, and an impressive silence spread over the whole company when the news was given by Capt. Pratt that Etahdleuh’s Doanmoe was dead. A braver, more simple, more true, more faithful Indian did not live.”

Enlarge

Etahdleuh’s 1876 ledger drawings are being offered in Heritage Auctions’ Ethnographic Art auction scheduled for June 26, 2018. In these brilliant, early depictions of his life before 1875, re-discovered after the passage of nearly a century and a half, Etahdleuh Doanmoe, Hunting Boy of the Kiowa, lives again.

“This book of ledger drawings is one of the most exciting lots to come up for auction in a very long time,” says Delia E. Sullivan, director of American Indian Art at Heritage Auctions. “The fact that it is intact – not cut up into individual pages like so many others – makes it an important historical document, and one with beautiful artwork. I expect both scholars and collectors to bid vigorously for this prize lot.”

MIKE COWDREY is the author of several books on American Indian art history.

This story appears in the Spring/Summer 2018 edition of The Intelligent Collector magazine. Click here to subscribe to the print edition.