NO MATTER YOUR WISHES FOR YOUR COLLECTIBLES, BE CLEAR ABOUT YOUR INTENTIONS AND INVOLVE YOUR HEIRS

By James Halperin and Greg Rohan

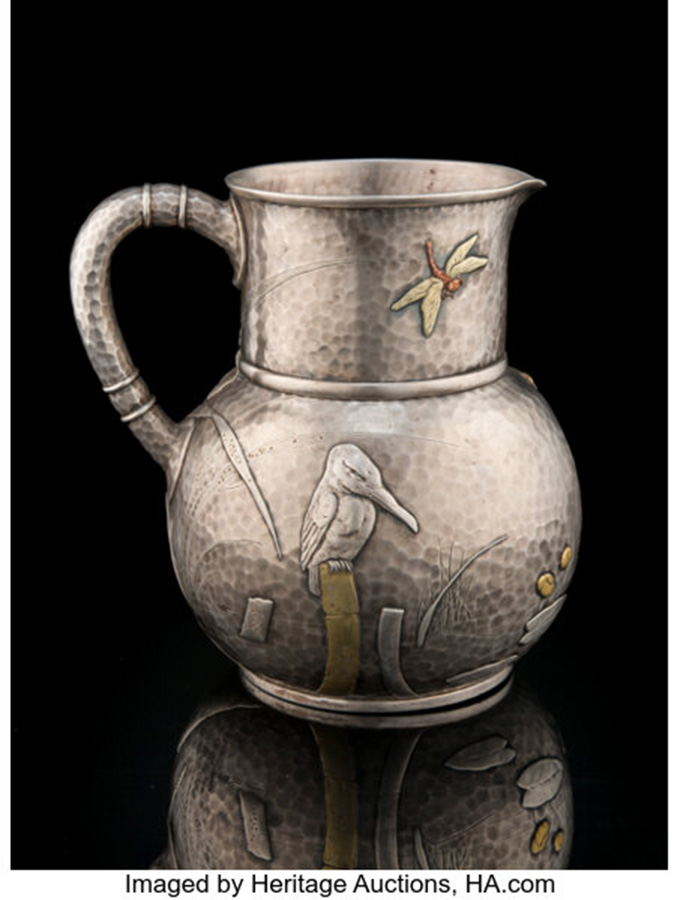

Every day, there is a story on some website, magazine or cable news network that illustrates the importance of having a current estate plan. Jimi Hendrix died in 1970, and his estate was subsequently the subject of 30 years of litigation – a very un-rock ’n’ roll epilogue to an incredible career. Picasso was revered as a business genius during his lifetime, but when he died in 1973 without a proper will, his many heirs were thrust into chaos. It took six years and a reported $30 million in expenses to divide up his estate. And when the musician Prince passed away in 2016 without a will, a sizable estate was left hanging in limbo.

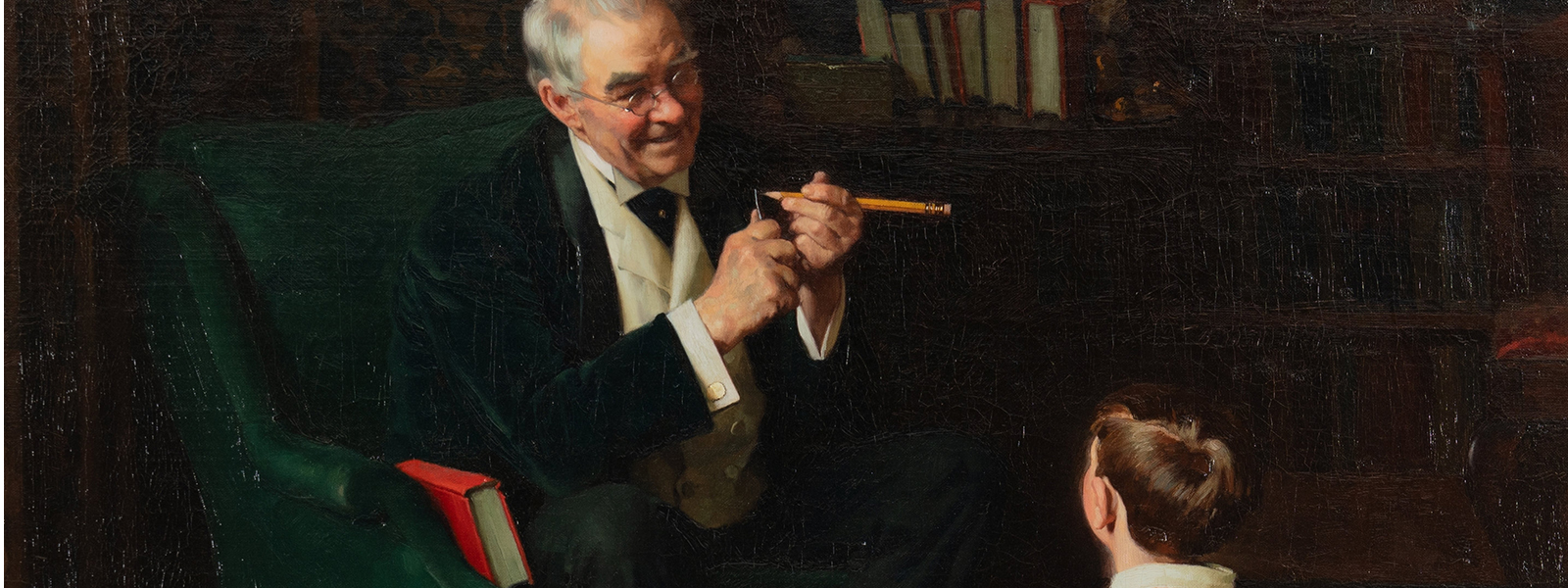

One recent survey found that half of Americans with children do not have a current estate plan. Most people try to avoid contemplating their own demise, and many collectors are equally reluctant to consider the sale of their treasures. As Woody Allen once told his physician, “Doctor, I’m not afraid of dying. I just don’t want to be there when it happens.”

Whether you intend to collect until the end of your life or sell next month, much of the same advice applies. Heritage Auctions has assisted thousands of people in disposing of their collections, and more than 20 percent were heirs who possessed little knowledge of art and collectibles. Sadly, uninformed heirs – who are grappling with grief and an enormous number of administrative challenges – are easy prey for unscrupulous opportunists. Our goal at Heritage always has been to ensure that the fruits of a collector’s pursuits accrue to his or her rightful heirs.

Involve Your Family

Many collectors keep their families in the dark regarding the scale and nature of their collecting; there are many reasons for this, but consider taking a longer view. Have you thought about the effect that your sudden death or incapacitation might have on your collection? What would you expect from your heirs? What should be done with your collection? Should it be sold? Distributed among family members? Some combination? What will remain after taxes?

One call from a widow took us to a house where we found a dining room table covered with boxed world coins that were stacked three feet high. From a distance, it was one of the most impressive collections that we ever had inspected: all matching coin boxes, each neatly labeled with its country of origin. The widow told us that her husband had been a serious collector for more than three decades, visiting his local coin shop nearly every Saturday. He then came home and meticulously prepared his purchases, spending hour upon happy hour at the table in his little study.

We opened the first box and couldn’t help but notice the neat, orderly presentation: cardboard 2×2 coin holders, neatly stapled, with crisp printing of country name, year of issue, Yeoman number, date of purchase and amount paid. We also couldn’t help notice that 90 percent of the coins had been purchased for less than 50 cents and the balance for less than $1 each. The collection contained box after box of post-1940 minors – all impeccably presented and all essentially worthless.

We asked the widow if she had any idea of the value of the collection. She replied that she knew rare coins were valuable, and since her late husband had worked so diligently on his collection for so many years, she assumed that the proceeds would enable her to afford a nice retirement in Florida.

We had to carefully explain that we couldn’t help her with the sale of the coins. Her husband had enjoyed himself thoroughly for all those years, but he had never told her that he was spending more on holders, staples and boxes than he was on the coins. With her dreams of a luxurious retirement diminished, we advised her to contact two dealers who routinely purchase such coins. The fault was not in his collecting, but in his failure to inform his wife of the nature of the collection.

We more typically encounter widows and heirs at the other end of the spectrum. When your spouse spends $50,000 or $100,000 on rare coins or other collectibles, you generally have some knowledge of those purchases, but not always – and often, the most prodigious collectors are coy with their family about just how much they’re investing. This leads to the more enjoyable surprises – those made-for-TV moments when we inform unsuspecting heirs of the vast fortune they’ve inherited.

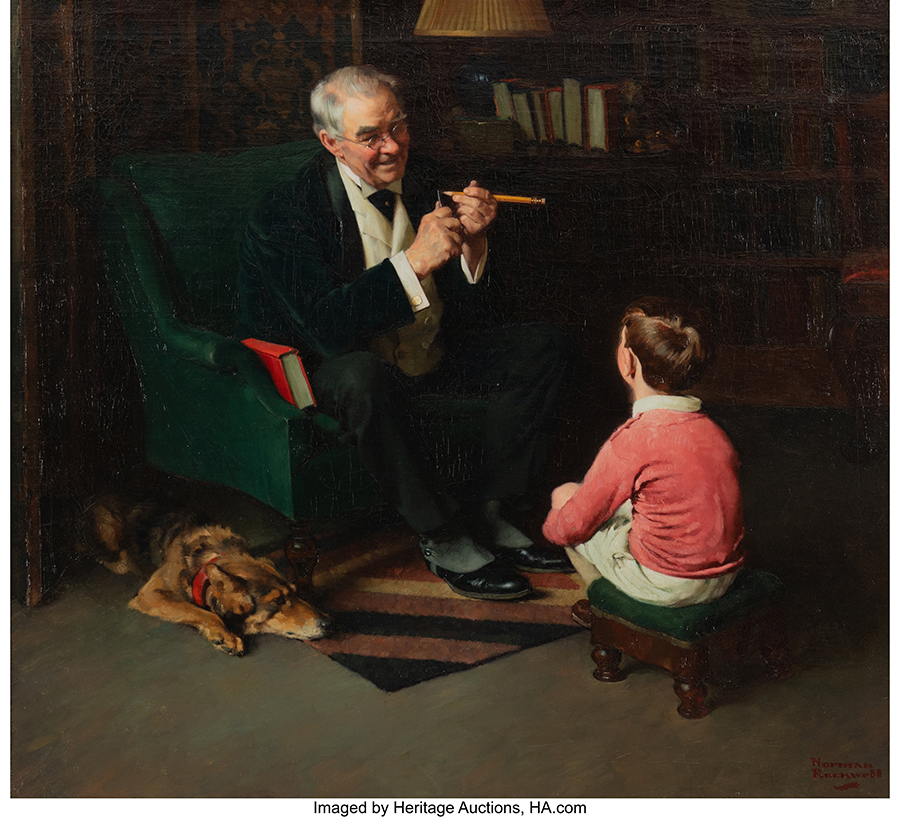

Years ago, we encountered the younger of two sisters who were dividing their father’s estate. He had left Germany in the early 1930s and brought to America two collections: antique silver service pieces and his rare coins. The coins were sold mostly to establish his business in Iowa. Despite the hard times, he prospered and was able to devote the next 30 years to rebuilding his collection of German coins. At the same time, he continued to expand his collection of 17th– and 18th-century German silverware. We knew every aspect of his collecting history because he left a meticulous record on index cards. Every coin and every piece of silver were detailed with his cataloging and purchase history. His daughter was in awe of his passion for maintaining such detailed records.

After his death, his daughters decided to split his collections between themselves. They added up the purchase values of each of his collections, which were just about equal. The older sister/executor had acquired some small knowledge of antique silver, and since she wished to keep all of the elegant heirloom tea service for herself, she decided to keep the silver and give her younger sister the coins – she definitely was not interested in splitting. After selling the nonfamily silver pieces through a regional auction house, she boasted of realizing more than $200,000 from her father’s $27,000 investment.

The younger sister came to us with only one box of his coins. Her father’s records for that box indicated a cost of less than $2,000, but knowing the years he had collected, we were anticipating at least a few nice coins. However, we were totally unprepared for what came next: pristine coins of the greatest rarity. His $2,000 box was worth more than $150,000, surpassing all our wildest expectations.

She then produced the record cards for the rest of the collection, and we offered to travel back to Iowa with her the same day. When we finished auctioning the coins, she had realized more than $1.2 million.

In another situation, the wife of a deceased coin dealer called us to consign $1 million in rare coins from his estate. This asset represented a significant portion of her retirement assets. We eagerly picked up the coins and already had started cataloging and photographing when we received an urgent phone call from her attorney. The coins had to be returned immediately. It appeared that her husband had been holding the extensive coin purchases of his main customer in his vaults, and he had neither informed his wife nor adequately marked the boxes. Most of her $1 million retirement asset belonged to her husband’s client and not to her husband.

A final example that really distressed us demonstrates that partial planning, no matter how well intentioned, cannot always guarantee the desired outcome. A collector with sizable holdings divided his coins equally (by value) between his adult son and daughter, with instructions that they should seek expert advice before selling. After the daughter came to us, she was pleased to learn that her coins were worth in excess of $85,000.

Once she signed the consignment agreement, she told us the rest of the story. Her brother had “sold” his share eight months earlier to a local pawnbroker for less than $7,500. Her father hadn’t shared his knowledge of the asset’s value with his children for fear that his son would spend the money foolishly. Instead, her brother basically gave it away.

So, what should you do to prevent such problems?

If transferring your collection to the next generation is desirable, you will want to provide for an orderly transition. If they aren’t interested in sharing your love of the collectibles, you will have to decide whether to dispose of the collection in your lifetime or leave that decision to your heirs. If the latter, your family should – at a minimum – have a basic understanding of your collection, its approximate value and how you want it distributed.

Important Questions To Be Discussed

- Are there heirs who will want the collection from a collector’s standpoint?

- Where are the objects kept?

- Where is the inventory of the collectibles kept?

- What is the approximate value of the collection?

- Has the collection been appraised or insured? If so, where is that appraisal, and does it need to be updated?

- Do any of the articles in your possession belong to someone else?

- Are there certain dealers or other experts you trust to provide guidance to your heirs?

- Is there a firm that you and your heirs wish to use in the collection’s disposition after your death?

The horror stories that begin this article are all true, none are isolated cases, and they won’t be the last. For whatever reason, if you cannot allow yourself to share this information with your whole family, choose one trusted individual – perhaps the person you are considering to be the executor or trustee of your estate. If that doesn’t satisfy you, please take the time to write detailed instructions and leave them in your safe deposit box or wherever you keep your valuables.

This article is excerpted from The Collector’s Handbook: Tax Planning, Strategy and Estate Advice for Collectors and Their Heirs.

JAMES HALPERIN is Co-Chairman and Co-Founder of Heritage Auctions.

JAMES HALPERIN is Co-Chairman and Co-Founder of Heritage Auctions. GREG ROHAN is President of Heritage Auctions.

GREG ROHAN is President of Heritage Auctions.