TWO RARE WORKS FROM THE COLLECTION OF BILL WATTERSON’S LONGTIME EDITOR COME OUT TO PLAY IN FALL COMIC ART AUCTION

By Robert Wilonsky

Anita Salem remembers well the night her husband brought the young cartoonist to dinner at their Kansas City home – this “kid” with close-cropped dark hair, big round glasses, a thick mustache, a wide grin. This was their regular custom whenever Lee Salem, for 40 years the editor or president at Universal Press Syndicate, was considering someone new to help fill the funny pages of daily newspapers around the country.

COMICS & COMIC ART SIGNATURE® AUCTION 7283

Nov. 17-18, 2022

Online: HA.com/7283a

INQUIRIES

Todd Hignite

214.409.1790

ToddH@HA.com

This was in 1985, when Salem was vice president and editorial director at Universal. By then, he already counted among his finds For Better or For Worse’s Lynn Johnston and Cathy’s namesake Cathy Guisewite; Salem, who also worked with Garry Trudeau and Gary Larson, was fast accruing a reputation as the “Champion of Quirky Cartoonists,” as The New York Times would later call him. So when this 27-year-old editorial cartoonist from Chagrin Falls, Ohio, showed up for dinner, it was business as usual. Except there was nothing typical about Lee Salem’s latest discovery. That night at dinner, he quickly drew two sketches for the Salem children, one of whom, 10-year-old Matt, had declared that this young cartoonist had created the “Doonesbury for kids.”

That strip was Calvin and Hobbes by the Salems’ dinner guest Bill Watterson, whose creations – a 6-year-old boy and his talking (stuffed) tiger – once appeared in more than 2,400 newspapers. The strip ran for a startlingly (and, for its fans, crushingly) brief period: from November 18, 1985, until December 31, 1995. Yet despite that short run, it ranks among the greatest comic strips of all time – No. 2 on a recent Comic Book Resources list, behind only Charles Schulz’s Peanuts.

“Bill is a real artist,” Anita says. “But more importantly, he remembers and captures those childhood moments that remind us of our own youthful experiences. He has that rare combination of imagination and artistic talent that makes him one of the truly great cartoonists.”

Heritage Auctions is proud to offer two of Watterson’s original Calvin and Hobbes pieces in its November 17-18 Comics & Comic Art Signature® Auction. Each comes from Lee Salem’s collection.

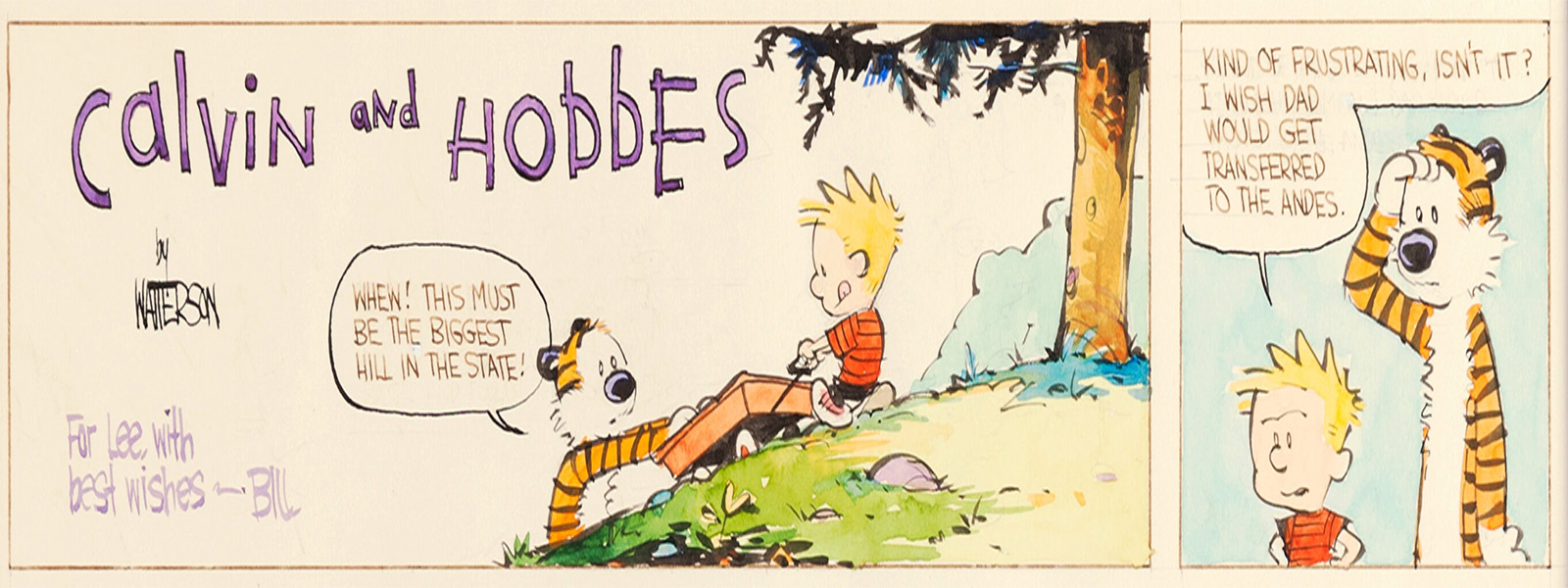

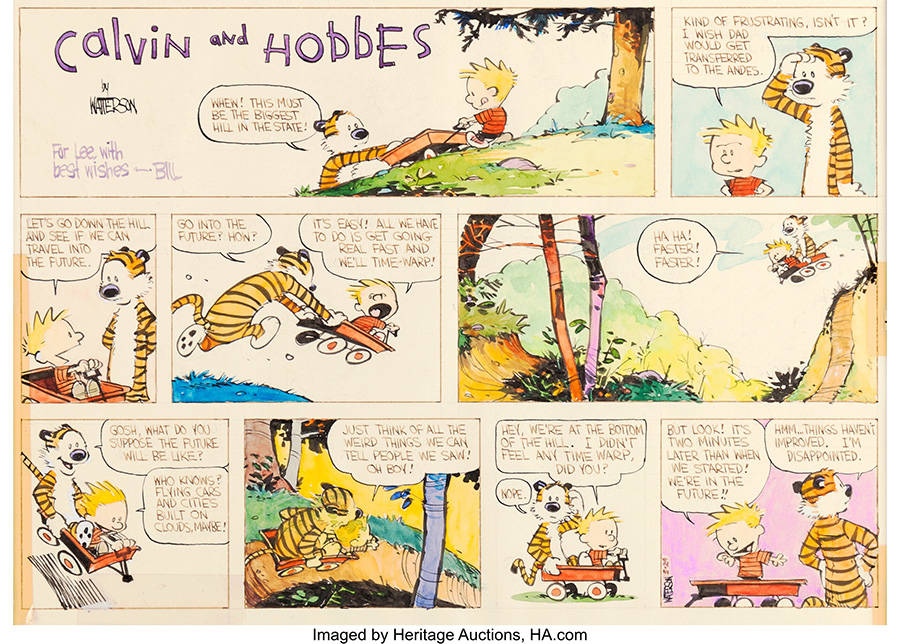

One is a stunning hand-colored Sunday strip from May 24, 1987 – only the second such piece by Watterson to ever appear at auction. It’s quintessential Calvin and Hobbes, beginning with the boy and his best friend perched atop a hill, hoping their red wagon will hurtle them into a time warp and a future filled with “flying cars and cities built on clouds, maybe!” Calvin, forever the only child looking for a way to escape into a different time or a better, more exciting place, instead finds himself at the bottom of the hill – two minutes into the future, better than nothing. “Things haven’t improved,” says Hobbes. “I’m disappointed.”

Watterson left a note in the title panel for his editor: “For Lee with best wishes – Bill.”

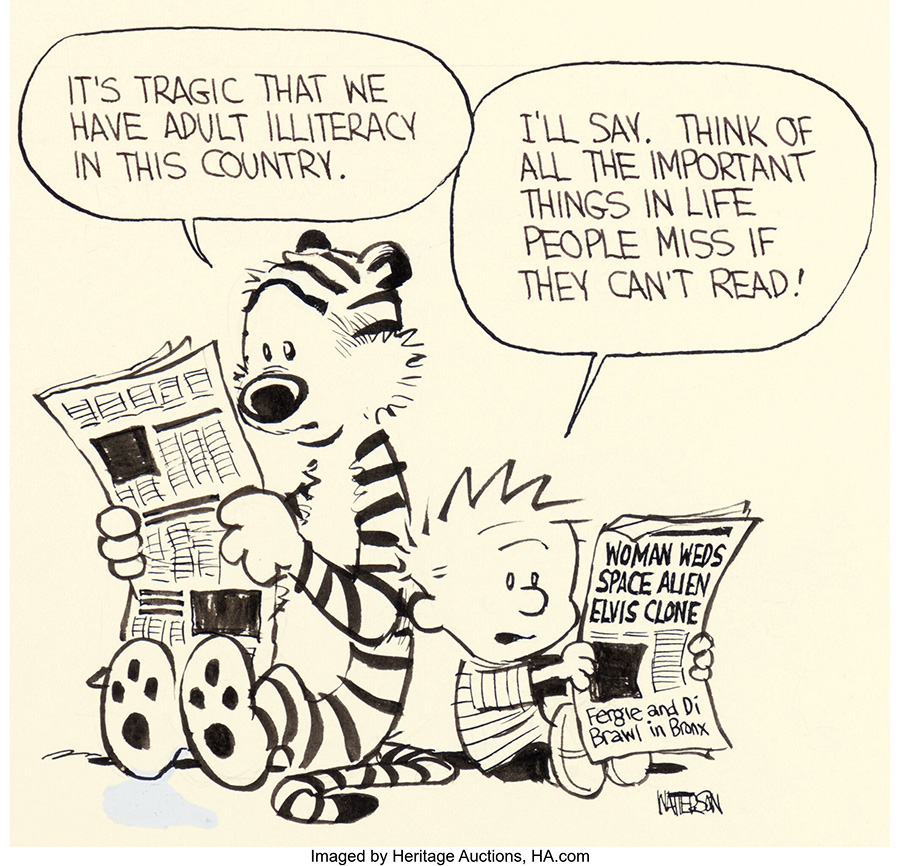

The second work is an unpublished one-panel specialty piece in which Calvin and Hobbes sit back-to-back reading newspapers – an image that now seems a throwback to a faraway moment. Hobbes laments, “It’s tragic that we have adult illiteracy in this country,” to which Calvin responds, “I’ll say. Think of all the important things in life people miss if they can’t read!” The boy holds a paper bearing such headlines as “Woman Weds Space Alien Elvis Clone” and “Fergie and Di Brawl in Bronx.”

Watterson drew this in 1988. It remains as timely as tomorrow.

“We get asked about original Calvin and Hobbes artwork more than any other comic art in the history of the medium,” says Heritage Auctions Vice President Todd Hignite. “Watterson’s work is virtually impossible to find, and this particular Sunday strip is absolutely perfect in every way – without question the best example to ever come to auction, as well as being one of the greatest to exist in private hands. This is one of those very rare, special opportunities, not least because of the unbeatable provenance, and we couldn’t be more honored to be working with Lee Salem’s family.”

If one needs proof that Watterson’s creations remain as beloved as ever, look no further than September, when a hand-painted daily strip from 1992 sold at Heritage for $216,000 – a record for any Calvin and Hobbes original. His work is more valuable than ever.

Yet it has always remained viable, cherished, essential.

Watterson always claimed he never got why the strip was so popular. “Really, I don’t understand it, since I never set out to make Calvin and Hobbes a popular strip,” he told his friend and fellow cartoonist Richard West in 1989. “I just draw it for myself. I guess I have a gift for expressing pedestrian tastes. In a way, it’s kind of depressing.”

He could be as modest as he was perceptive. Long after he canceled the strip, Watterson shrugged off those who would ascribe deep meaning to his work: “If you draw anything more subtle than a pie in the face [in comics], you’re considered a philosopher.” (Which bears a striking similarity to something Calvin once said in a famous strip: “As my artist’s statement explains, my work is utterly incomprehensible and is therefore full of deep significance.”)

But there has been no shortage of adoring essays in recent years exploring Watterson’s work and its resonance into the 21st century, to both children who seek solace and wonder in a Land of Make-Believe and the parents who can only roll their eyes. Look no further than Star Wars novelist and bestseller Chuck Wendig’s 2020 essay on how Watterson and his strip prepared the world for the isolation wrought by a global pandemic. What at first seemed like a stretch dug deep into the appeal of Watterson’s creations:

“Calvin was trapped with his parents, with teachers, with the limitations of childhood,” Wendig wrote. “A day he wanted to spend with Hobbes was spent seated in a classroom. Then there’s bathtime. Or swimming lessons. Or buckled up in the car as his mother runs errands. In lockdown, we’re all in the house on a rainy day. Caught in endless Zoom meetings for work or, if we have kids, in school. (We’re all in the classroom now.) We all are in our own heads, and we all just wanna go out and play.”

Salem himself spoke about the appeal of Watterson’s work for a 30th-anniversary interview. He was asked what first caught his eye about Watterson’s work – what, perhaps, did he see in that man and his strip that garnered a dinner invite.

“It was so breathtakingly simple, fresh and professional that I had to set it aside with the thought, ‘This can’t be as good as I think it is,’” Salem said. “On a second look and subsequent looks, it was. It still is, to my mind. Bill had taken a near-universal situation – a child with an imaginary friend – and turned it into something archetypal.”

Salem said that all those initial submission strips made it into print.

Anita says she now parts with these pieces only because it’s time someone else can enjoy them as much as she and her family have these last few decades. But more importantly, she says, she doesn’t want these valuable works stashed in a vault.

“It doesn’t seem right to me that they would be sitting alone in the dark,” she says. Because Calvin and Hobbes will always want to go exploring.

ROBERT WILONSKY is a staff writer at Intelligent Collector.

ROBERT WILONSKY is a staff writer at Intelligent Collector.