ARTIST KNOWN AS ‘THE ENGLISH MURILLO’ DEVOTED HER BRUSH TO IMAGES OF HARD-WORKING PEASANTS, TRADESPEOPLE AND STREET URCHINS

By Marianne Berardi, Ph.D., and Janell Snape

EVENT

EUROPEAN ART SIGNATURE® AUCTION 8047

June 4, 2021

Online: HA.com/8047a

INQUIRIES

Marianne Berardi

214.409.1506

MarianneB@HA.com

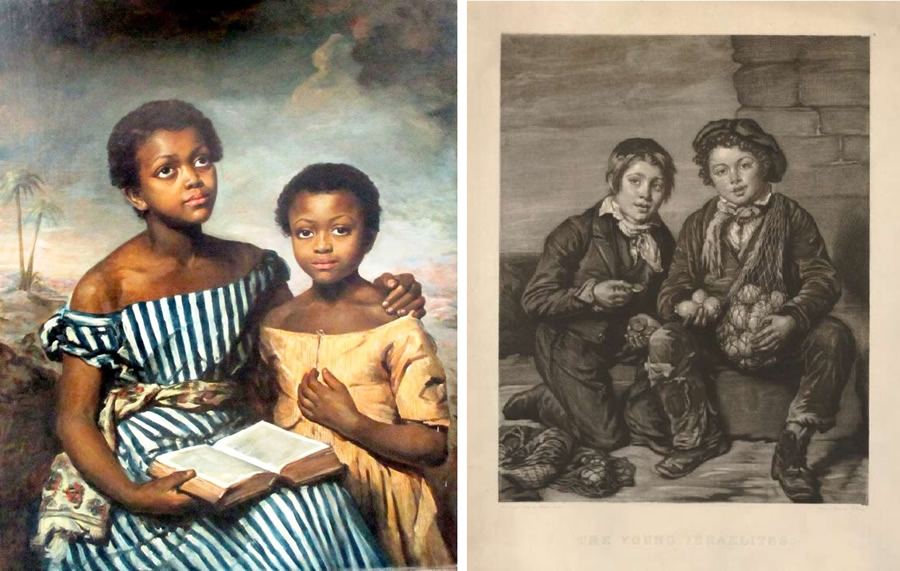

The author of this lush painting of two children selling flowers (1836) was the British child prodigy Elizabeth Emma Soyer (née Jones), who flourished during the late Georgian and early Victorian period. During her short but eventful life (she died of complications during childbirth at age 29), she was celebrated both in England and on the continent with the moniker “the English Murillo,” owing to the remarkable characterizations she was able to achieve in her portraits and genre scenes. Like the 18th-century Spaniard to whom she was compared, and whose work was especially prized in Britain during her lifetime, Emma Jones Soyer (1813-1842) produced some traditional portraits but devoted her brush primarily to images of hard-working peasants, tradespeople and street urchins painted with a candor and sensitivity that resonated with quiet dignity. Her palette is deep and rich like Murillo’s, and the forms beautifully drawn and modeled – all of which give the work a level of gravitas more akin to Old Master painting than Victorian imagery. Perhaps she even outdid Murillo in one regard: Her work, while empathetic, tended to stay this side of sentimental. In the present work, for example, the young flower sellers engage the viewer directly with expressions that are open but not saccharine.

Although she died young, the artist left behind a prolific output, a total of 403 paintings as recorded in her obituaries. To date, however, few of her paintings have been traced either in collections within the United Kingdom or in Europe where she also exhibited. That so many works seem to have nearly entirely vanished is a mystery that fans of her few extant efforts find baffling. Fortunately, some of her compositions are known through engravings and mezzotints made after them, both during her lifetime and afterwards, which served to popularize her work. (See prints after her paintings The English Ceres and The Young Israelites in the British Museum, inv. nos. 2010,7081.5723 and 2010,7081.6440). These prints provide valuable visual clues to the nature of her achievement. Judging from them, and the few canvases, such as the present painting, which have surfaced on the art market, the artist’s celebrity was certainly richly deserved.

Born in London, Emma Jones lost her father when she was just 4, but was raised by an extraordinarily attentive mother who spotted her daughter’s precocity early, and lost no time providing her with an enriching education. As a young girl, through tutors, she gained fluency in French and Italian, and when she showed musical inclinations, Mrs. Jones engaged no random music teacher but rather the French-born violin-virtuoso, pianist and composer, Jean Ancot (1779-1848), who was in England serving as pianist to the Duke of Sussex. Emma was such a gifted pianist that it seemed a foregone conclusion that she would choose a musical career. But once she began drawing, it became clear that the polymath had found her métier. Her mother engaged a Belgian portrait painter, François Simonau (1783-1859), himself a student of Baron Gros, who had opened a drawing and painting academy in London. Under Simonau’s instruction, her talents blossomed to such a degree that he dedicated himself completely to her education. In 1820, he also became her step-father when he and her mother married. Emma became one of the youngest artists ever to exhibit at the Royal Academy when, in 1823, at the age of 10, her Watercress Woman was accepted for inclusion. By the age of 12, she had drawn more than 100 portraits from life with surprising fidelity.

Enlarge

Two Young Children with a Basket of Flowers, 1836

Oil on canvas laid on canvas

28 3/8 x 36 in.

Estimate: $20,000-$30,000

Once her career was launched in England, Emma exhibited her work regularly: She showed a total of 14 works at the Royal Academy between 1823 and 1843; 26 at the British Institution (between 1831 and 1837); and 14 at the Royal Society of British Artists, Suffolk Street. The present work may have been the canvas entitled Two Children with Flowers, which she exhibited at the 1837 British Institution exhibition (a year after it was painted), and which was listed as number 206 in their records for that year. She signed her work simply – either E. Jones or E. Soyer – for after her marriage (unlike many women artists) she continued to paint. Her reputation soon spread to Europe, and beginning in 1840, she exhibited at the Paris Salon for three years straight. Judging from numerous contemporary accounts (notably sterling critical reviews in French papers), her reputation in France seems to have stood even higher than in her native country. The French seemed to have been especially taken with the fact that she had been a prodigy.

In London on April 12, 1837, Emma Jones married Alexis Bénoit Soyer (1809-1858), an extremely handsome and charismatic French chef, who went on to become the most celebrated cook of the Victorian period. According to Soyer’s entertaining Memoirs, the painter and cook first met at her home in London Street in 1835 when Soyer came to have his portrait done by François Simonau. The two seem to have formed an attachment almost immediately.

Soyer was a man who lived large, with tremendous gusto, and embraced projects that would have daunted most people. Escaping from French mobs on the eve of Charles X’s resignation in 1830, the 20-year-old Soyer fled to England and secured employment with the Duke of Cambridge’s household, where his brother was head chef. Then, from 1837 to 1850, he served as chef of the newly-built Reform Club in London – the post which made his reputation and also allowed full-rein to his creative powers. He designed the innovative kitchens there with Charles Barry, which became so famous that they were open for conducted tours by the public. On the occasion of Queen Victoria’s coronation, he managed the Herculean task of feeding 2,000 members and their guests. At the Club, he instituted many innovations, including cooking with gas, refrigerators cooled by cold water, and ovens with adjustable temperatures. His princely salary was more than £1,000 a year and “Soyer’s Sultana’s Sauce” was marketed for him through Crosse and Blackwell in an exotic bottle with a label featuring Soyer himself, unmistakable in his trademark cocked hat that was based upon a portrait by his wife. Even though by many accounts he was quasi-illiterate, he managed to publish several best-selling books about cooking, which he apparently dictated to secretaries. He designed a portable field stove for use by the British army during the Crimean War, and also, distraught by the Irish famine, went to Ireland himself where, through his efforts, government-supported food kitchens were set up in Dublin to feed the starving. And despite his own mountain of personal projects, he was an enthusiastic supporter of his talented wife’s artistic career.

Enlarge

Following her marriage and with her artistic star on the rise, Emma Soyer found that she could barely keep up with requests for portraits in oil from the aristocracy throughout England. She made the decision to travel, accompanied by Simonau, to fulfill commissions for clients in their own residences rather than require they come to her London studio for their sittings. Additionally, owing to his access to the glitterati whom he met through the Reform Club, Alexis Soyer was able to steer commissions towards his wife. Her portrait of him, as a chef, which still hangs at the Club, was an important piece of visual promotion.

In 1842, one such group of VIPs visited the Reform Club, eager to meet Soyer and see his revolutionary kitchens. Among them was the Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, the father of Queen Victoria’s husband, Prince Albert. Upon seeing Emma’s paintings, he was so taken with her talent that he asked Alexis if he would kindly accompany him to Belgium to meet with his younger brother, King Leopold of Belgium, who as a great art collector would relish seeing some examples of Emma’s painting firsthand. Alexis was apparently hesitant to make the trip, since his wife was pregnant and unable to travel, but she encouraged him to do so. Sadly, during his absence, Emma went into premature labor and died the night of Aug. 29-30, 1842 owing to severe fright, which various contemporary accounts say had been caused by a ferocious thunderstorm. Utterly distraught, Soyer erected a massive funerary monument to her at Kensal Green Cemetery in London, which featured a portrait bust in high relief of the artist based upon her final self-portrait. The monument was the work of King Leopold’s own royal sculptor, Pierre Puyenbroeck – a testament to the fact that Soyer spared no expense. Soyer also devoted himself to numerous charitable causes in his wife’s memory. One of the most notable was the exhibition of 140 of Emma’s works displayed as “Soyer’s Philanthropic Gallery” at the Prince of Wales’s Bazaar in 1848, with an accompanying exhibition catalog which he published. The proceeds from this endeavor were donated to a number of soup kitchens located in several different districts of London.

At the time of his death in 1858, Alexis Soyer was not in the best financial situation. He had overextended himself, and following Emma’s death had experienced a rather spectacular failure of a costly restaurant venture. Once his debts were paid, his two brothers, both living in France, inherited his large collection of Emma’s paintings, which seems to have been the bulk of her oeuvre. Since that time, apart from her portrait of Alexis which remains in the Reform Club, London, only a smattering of works by her hand have been indicated by location. The biographical dictionary Bénézit (1966) listed two works, one in Gotha (a Portrait of a Celebrity and doubtless a purchase by the Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha), and one in Cahors described as a Vendor of Plaster Figurines. A work from her hand described as a Female Merchant and Her Son sold at a Paris sale on March 18, 1929. More recently, her 1835 Grandmother at Her Spinning Wheel, which she exhibited in 1836 at the British Institution, appeared at Hampel Auctions in Germany on March 27, 2009; and her 1839 portrait of an older peasant woman in a cap appeared at auction in Madrid (Dec. 19, 2017).

In 2018, one of the most remarkable paintings by Emma Soyer to emerge features two black girls in a tropical landscape, which she painted in 1831 for the abolitionist cause in England, although it was never publicly exhibited in her lifetime. The painting was featured in the BBC television program Fake or Fortune, having emerged from a French collection, suggesting perhaps that more of her works remain in French hands, unrecognized perhaps as “School of Murillo.”

Two Young Children with a Basket of Flowers by Emma Jones Soyer being offered by Heritage Auctions comes from a private collection in Lewisville, Texas. Two years ago, the present owner astutely spotted it in a small midwestern auction, where it was under-described. Its history prior to the 2019 sale remains as much a mystery as the bulk of this talented artist’s production, which we can hope, through our new imaging tools and the power of the internet, will eventually come to light.

MARIANNE BERARDI, Ph.D., is a Senior Specialist in the Fine & Decorative Arts department at Heritage Auctions.

JANELL SNAPE is an Associate Specialist and Cataloger in the Fine & Decorative Arts department at Heritage Auctions.

This article appears in the Spring 2021 edition of The Intelligent Collector magazine.