WILLIAM HENRY’S MATT CONABLE FINDS INSPIRATION IN HOBBY’S MOST FASCINATING TREASURES

By Stacy Suaya

Of all the things he does at William Henry – a luxury brand that makes some of the world’s most exquisite pocketknives – founder and chief designer Matt Conable speaks with a certain delight about checking the mail. Why? “Looking for goodies,” he says, like a kid with two quarters and a close proximity to a gumball machine.

Packages arriving at his Oregon studio contain finished knives, often from far-flung places like New Zealand, Italy or Hungary, and when he opens them, he is often completely surprised. That’s because after he and his 40-person team craft the knives in their studio, they are shipped as “blank canvases” to master engravers all over the world, who return them transformed into one-of-a-kind masterpieces.

There is no design approval process.

Enlarge

“We say, ‘Here’s a knife we made. We believe in you. Do what you want. And when you’re done with it, we’ll write you a check and present it to the world.’ We end up with extraordinary work,” Conable says, “and they get a chance to play.”

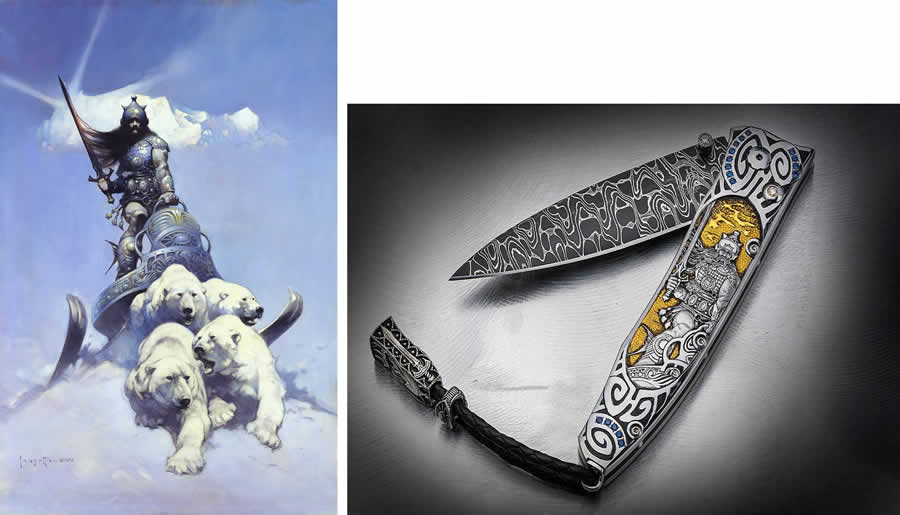

The engravings can take several months, and scenes that have played out on the “canvases” have included American Indian chiefs, dragons and, in the case of a recent creation, an etching of Frank Frazetta’s 1972 painting, The Silver Warrior. That knife runs $75,000. Frazetta, of course, is well known to comic and illustration fans. His paintings in the 1960s created a new look for fantasy and science-fiction novels. His original paintings often sell at auction for six figures, with some pieces surpassing $1 million.

WITH A PROVEN ABILITY to fetch high figures, you might think Conable set out to be a knife-maker, but he didn’t. On a summer night in Santa Cruz, Calif., when he was on break from studying industrial and labor relations at Cornell, an old hippie approached him at a party and liked the way he played piano. The hippie owned a knife shop nearby, and he wanted Conable to apprentice for him at $6 an hour.

Conable, disenchanted with school at the time, packed up and took the job – then quickly noticed how much he loved to see, touch and feel his work. The apprenticeship lasted two years, and afterward he moved to Prescott, Ariz. with his then-girlfriend to start their own artisan knife-making business out of a funky little house and horse barn on 62 acres.

Even though the knives Conable made during that time were recognized in juried shows like that of the Smithsonian, Conable returned to the Bay Area in 1997, broke and convinced that he needed to get an MBA. Fate cut in again, when a mysterious investor (and owner of one of Conable’s knives) came across his résumé. He called Conable and asked if they could start a business together. That business is now William Henry, a name that combines the two men’s middle names.

Enlarge

The William Henry process takes 12 to 15 months from pencil sketch to finished product, and the knives exist in a space all their own. The studio uses metal-forging techniques that samurai sword craftsmen originated 500 years ago, and incorporates exotic materials like fossilized mammoth teeth, dinosaur bones, and meteorites – alongside gemstones or Blacklip mother-of-pearl.

The uniqueness of William Henry pieces, Conable says, includes the hundreds of steps completed in the shop to the global dance that occurs afterward. The company works with at least four U.S. states and three countries on different parts of the process, which could mean a knife changes hands with a golden inlay artist in India or the blade is forged by a fifth-generation descendant of original samurai sword-makers in Sakai City, Japan.

FOR SELECT PROJECTS, ARTWORK on the knives has been rendered in a literal fashion. Most recently, the idea for the Silver Warrior knife was born when the Frazetta family approached Conable, hoping to bring the famous painting to 3-D life. Conable was a Frazetta fan, regarding him as a legend just behind Stan Lee. He ended up basing an entire collection on the single painting – the knife, plus 12 pieces of jewelry, including pendants, bracelets, necklaces and a ring. The folding pocketknife is hand-engraved with a warrior depicted on one side and polar bears on the other.

“Frank Frazetta was a bold, imaginative artist who set the standard for others who followed,” Conable says. “The Silver Warrior painting is a world unto itself, and each of these pieces has been designed to capture that spirit and tell the story.”

Enlarge

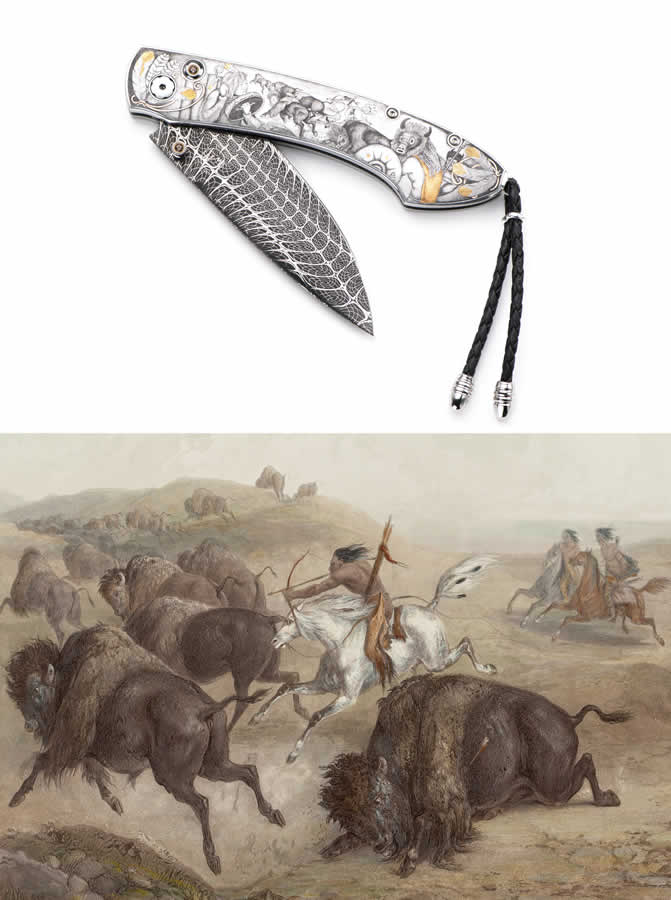

Before the Frazetta line, there was the B12 Bodmer knife, resultant of a conversation between Rick Thronburg, William Henry’s lead of engraved offerings, and master engraver Sam Welch. The two men both loved the American frontier era, and Welch mentioned his appreciation for the 1839 Karl Bodmer (1809-1893) painting called Indians Hunting the Bison. Welch eventually completed an engraving based on it that took more than 140 hours to produce.

When Conable designs the knives, there’s only one constant. He thinks of himself and what he likes, and how to make the best product possible. He never thinks of the “William Henry customer,” because they are all so different in background. Their only common trait is that they see beauty and craftsmanship through the same lens as Conable. “There is an unnamable soul to what we do that matters,” he says. “We turn a task into an experience, and a chore into a ritual.”

He leans back and says, “Those who get that will love carrying a William Henry.”

STACY SUAYA is a California writer who has written for the Los Angeles Times.