HOLLYWOOD PRODUCER MIKE KAPLAN HAS ALWAYS HAD AN EYE FOR THE ELEMENTS THAT MAKE A MOVIE POSTER GREAT

EVENT

MOVIE POSTERS SIGNATURE® AUCTION 7228

Nov. 21-22, 2020

Live: Dallas

Online: HA.com/7228a

INQUIRIES

Grey Smith

214.409.1367

GreySm@HA.com

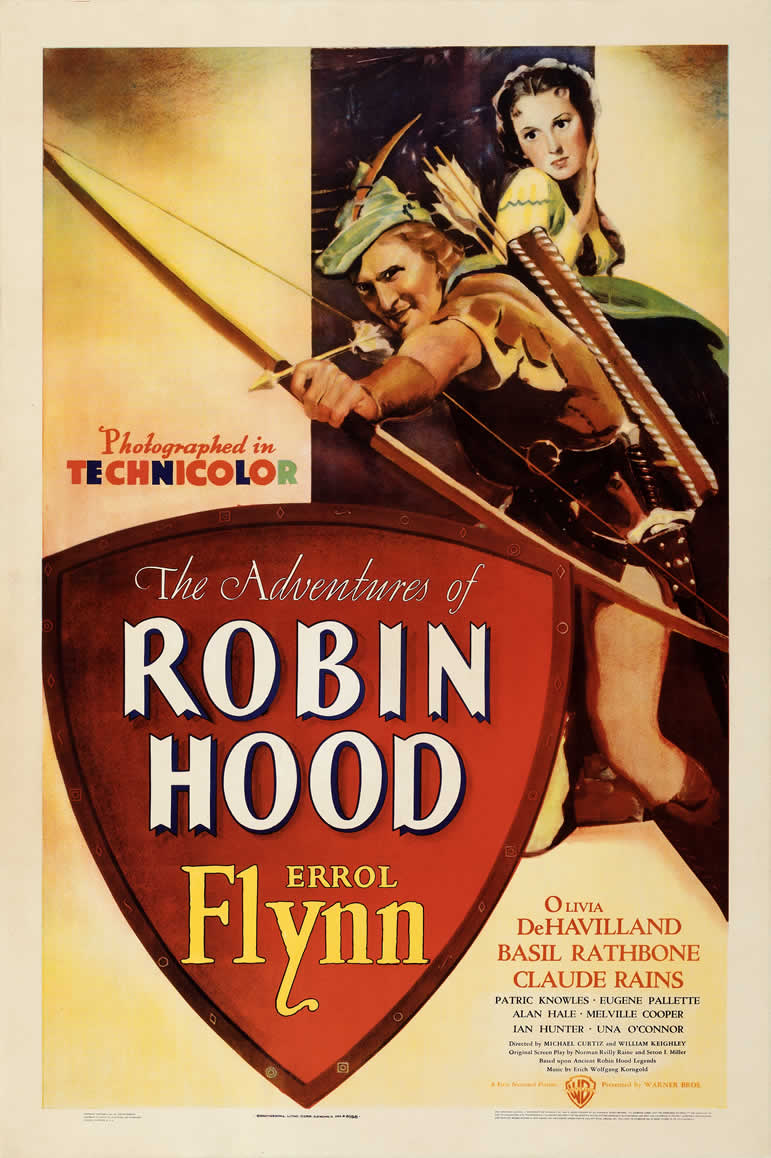

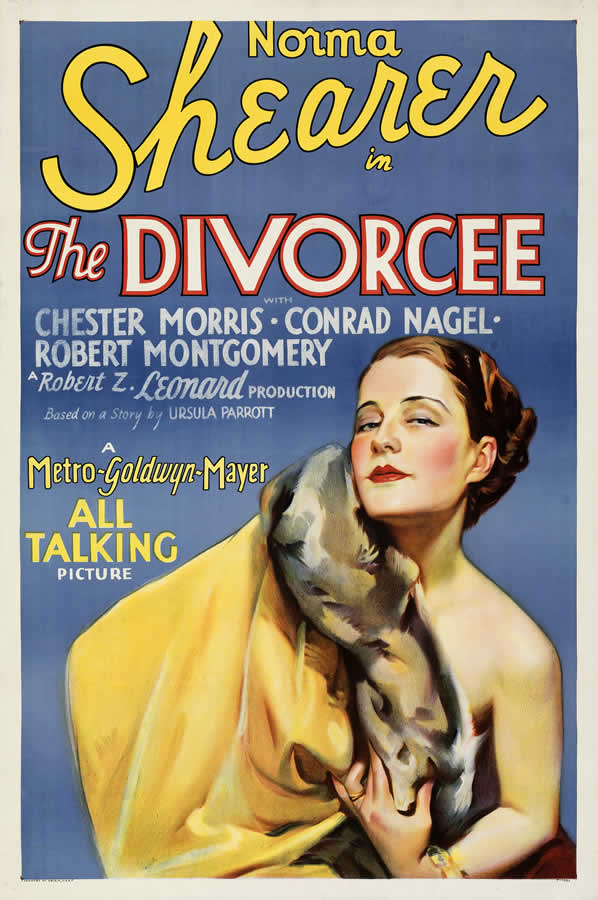

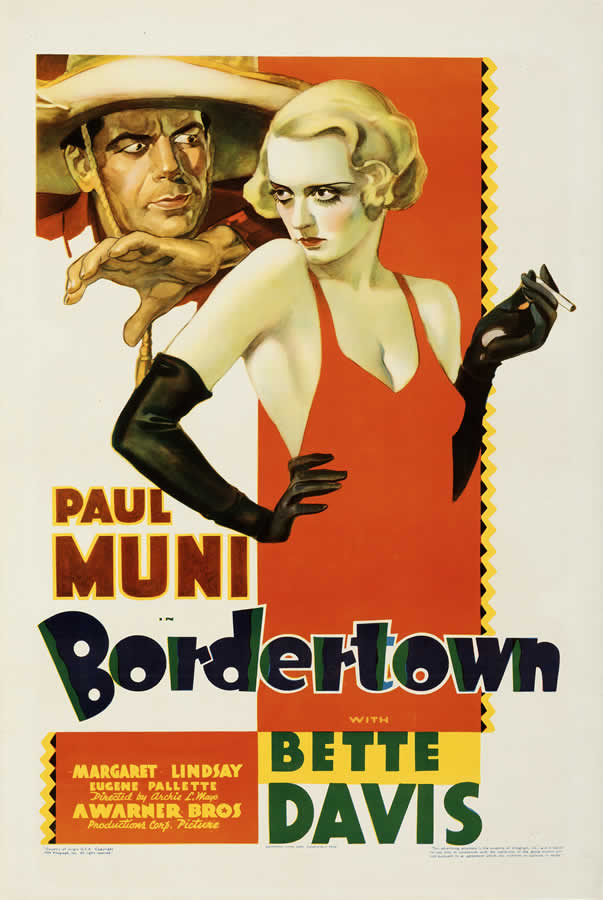

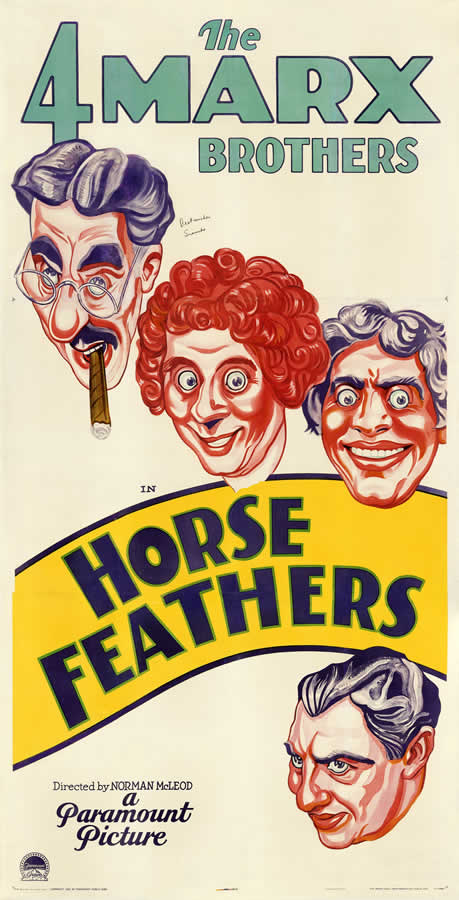

TOP OF THE TOPS

Great movies with great posters are rare. Here are some that make Mike Kaplan’s list:

- Stagecoach, Dawn Patrol, Sunny Side Up, Orphans of the Storm, Night at the Opera and What Price Hollywood? (U.S. releases)

- Tarzan the Ape Man and Death Takes a Holiday (Austrian releases)

- 42nd Street (Belgian release)

- Red Shoes (British release)

- Carefree and The Grapes of Wrath (French releases)

- Singin’ in the Rain, The Philadelphia Story and The Quiet Man (Italian releases)

- I Know Where I’m Going! (British and Danish releases)

- The Thin Man and Easy Living (large French double panels)

- Tabu, Sunset Boulevard, Midnight Cowboy and The Entertainer (Polish releases)

By Hector Cantú

Mike Kaplan has always appreciated the visuals of entertainment.

As a child growing up in Rhode Island, he would search for full-page Broadway ads in The New York Times and clip them out. “I would color them in,” he says, “and when I went to New York, I would compare the colors on the real ads to what I had done.”

Kaplan would later work as a marketing strategist in Hollywood, working with Stanley Kubrick on 2001: A Space Odyssey and helping to create the now-legendary movie poster for 1971’s A Clockwork Orange. Along the way, he put together one of the most important collections of movie posters – more than 3,000 pieces – from Hollywood’s Golden Era. The Los Angeles County Museum of Art and the National Museum of Dance are among the institutions that have exhibited his collection.

“Mike has an incredible eye for the best of poster art, as he comes from that film marketing background,” says Grey Smith, Heritage Auctions’ director of vintage posters. “His posters are an example of a connoisseur who has put together a great collection of the best artwork of classic films.”

Enlarge

Kaplan, who occasionally auctions pieces from his collection through Heritage Auctions, talked to The Intelligent Collector about his early days in the hobby, his collecting goals and why auctions make him happy.

You’ve said you were born with a “poster gene.” You began noticing ads in The New York Times as a child, correct?

My parents got The New York Times, and I immediately responded to posters in the paper. The first 10 pages or so of the arts section back in those days had full page ads of Broadway shows that were opening up.

So you had an early appreciation for the graphics of show marketing.

Exactly. And I also became an immediate fan of Al Hirschfeld, who was a great artist. He invariably would have, two or maybe three times a month in the Sunday paper, the front cover drawing of what was opening on Broadway, or what was about to open. I tended to like paintings and illustrations better than photography because I thought it was more artful.

When did you get into the entertainment business?

My first job out of college was in the trade press, as a journalist and critic, in 1964. Within a year, I was in the publicity department, first at AIP [American International Pictures] for about five months, and then I went to MGM in 1965. The posters from that period, beginning in the ’60s, late ’50s, were easiest for me to get. However, for the most part, the artwork on most posters of that time, from my point of view, were on an aesthetic decline. The best artwork at that point was being done with rock ’n’ roll covers. They were really dynamic. I always felt movie posters should be their equivalent.

Enlarge

When did you get your hands on your first movie poster?

When I was working at MGM, someone told me that I could get old movie posters. There were these funky memorabilia shops that sold old movie posters. I had no idea they were available. Even at that point, getting a movie poster was difficult because they were not sold commercially. They just went from one theater to another. I remember I was trying to find a poster for Gilda [1946], and even at that point, Gilda was a difficult poster to find. It was rare even then. I got into it a little bit and at one point I said, “I better not do this because I can see myself getting addicted to this.” This was in the ’60s. I had a few posters. One was The Postman Always Rings Twice [1946]. There was a famous ad line that MGM had when Clark Gable came back from World War Two … “Gable’s Back and [Greer] Garson’s Got Him.” It was a movie called Adventure [1945]. I remember I had that poster.

What have been some of the unconventional sources of posters in your collection?

MGM transferred me to Los Angeles. I was looking for a present for a friend of mine in a memorabilia shop called Chic-A-Boom on Melrose. I went in there and they had rows of movie posters in sleeves and the first one I saw was a poster for Irish Eyes Are Smiling [1944], a Fox musical with June Haver, stone lithography. It was very well designed for that genre. And I’d had a crush on June Haver when I was a kid. So I bought that, and that got me back into it. I still love that poster. It’s very well-designed.

Enlarge

When I went to New York there was a store on the lower east side, the Memory Shop. I would always spend a day or two down there. … At one point, I found in the Errol Flynn piles the top two-thirds of a three-sheet for The Dawn Patrol [1938]. I’d never seen it before. It was great artwork. Even though it wasn’t the complete poster, I wanted it anyway. I figured the bottom was probably just type anyway. And so I bought it. I went back to Los Angeles and by that point, restoration was coming into popularity. We all went to a restorer, his name was Igor, a painter from Russia. He would put a poster on linen, repair it, restore it and paint elements. I had an image of what the complete Dawn Patrol three-sheet looked like from a press book and so I was going to bring him my top of the three-sheet and the other image to put it together.

Well, I was selling a few things by that point in Movie Collector’s World, which was the main trade publication for collectors. So I put in an ad, and I asked if anyone had the bottom third of the three-sheet for The Dawn Patrol. By luck, within a week, I got a call or a note from someone in New Jersey who had it! And he was willing to sell it. I said, “Where did you get it?” And he said, “At the Memory Shop.”

Incredible…

What a fluke that was!

So the lesson is there’s no such thing as a silly question?

It was a last-minute thing because I was going to take it to Igor. I thought I’ll just try it. You never know what’s going to happen.

What has been the final element when you decide to acquire a poster for your collection? What is it that makes you scream “I need that!”?

It’s a variety of things, but when you get that buzz, that feeling in the pit of your stomach that you want it, you have to have it, it’s usually the image and how it’s constructed. I progressed from wanting certain people and certain styles and concocted in my head various exhibits that could be done with various themes that I saw in movie posters. I’ve done maybe 15 exhibits now, and that’s evolved from where I might not love the poster but I liked it and I saw something in it that would make it interesting for an exhibit. For example, how circles are used in film design. How actors smoke. People dancing in musicals, and non-musicals.

Enlarge

Dancing seems to be one important theme.

It was one, from the beginning, because I loved dancing and I loved Fred Astaire and Gene Kelly … all those people who were great dancers.

What do you know about movie poster collecting that you believe most collectors don’t know?

The foundation of my collection is based on design. For instance, Citizen Kane [1941] is undoubtedly one of the great movies, but the American posters for the movie, to me, are weak and don’t represent the film. One style, which is the most desirable, shows [Orson Welles] with two of the actresses, which makes it seem like a romantic triangle. The other one has an image of him standing that doesn’t even look like him, with bits and pieces of other characters in the background. It was a troubled film because of the whole [William Randolph] Hearst situation.

So just because it’s a great movie doesn’t mean it’s a great poster.

No. And it’s very, very rare that you find a great poster for a great film. Stagecoach [1939] is one. Al Hirschfeld’s A Night at the Opera [1935] poster. The Dawn Patrol poster I described earlier is a great poster. I can’t think of too many that are great posters for great movies. The Quiet Man [1952], the Italian poster, is a great poster.

Enlarge

Most collectors dream of displaying their collection in a museum. What’s the best advice you have for achieving that goal?

The main thing is that the object of the collection, I’ve always intended for it to go to a museum. With the Los Angeles County Museum of Art exhibit, I had been dealing with them for three years. The people there, the curator, the director of the museum, they got it. They knew the level of my collection and my eye, so to speak. They recognized a consistency in the visual totality of what I collected. Each piece had visual value. The LACMA is a world-class museum. So it’s difficult. It’s not easy. There’s always competition from other art forms. It comes down to persistence and struggle.

What’s the best thing about seeing your pieces in an auction?

The surprises. Maybe a poster you think is worth $800 goes for $4,000. Or people are thankful for the chance to add something to their collection. That means as much to me as whether or not it’s a record-breaking auction result.

You’re still collecting, right?

Yes, but not to the same degree. There’s always something that strikes my eyes. Why do I need to stop?

HECTOR CANTÚ is editor of The Intelligent Collector magazine.

This article appears in the Fall 2020 edition of The Intelligent Collector magazine. Click here to subscribe to the print edition.