SINCE 1978, HOLLYWOOD PRODUCER TOM TATARANOWICZ HAS CHAMPIONED HAL FOSTER’S NORDIC PRINCE

Interview by Hector Cantú ● Portrait by Axel Koester

AS A RESIDENT OF SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA, Tom Tataranowicz keeps his eye on the wildfires that every now and then rage through the hills. One of the last came within a quarter mile of his home.

“It’s pretty easy,” Tataranowicz says with a smile when asked which parts of his collection he would save. “All of it. It takes about 15 minutes to load everything up.”

Tataranowicz, an animation producer/director who’s worked on animated shows such as Iron Man, Fantastic Four, The Incredible Hulk, and Biker Mice From Mars, began collecting original comic art in the late 1970s. On his walls you’ll see original pieces by legends such as Frank Frazetta, Bernie Wrightson, James Bama, Walt Kelly, Neal Adams, Walt Simonson and Russ Manning. Among his most prized is a collection of original Prince Valiant strips that ranks among the best in private hands.

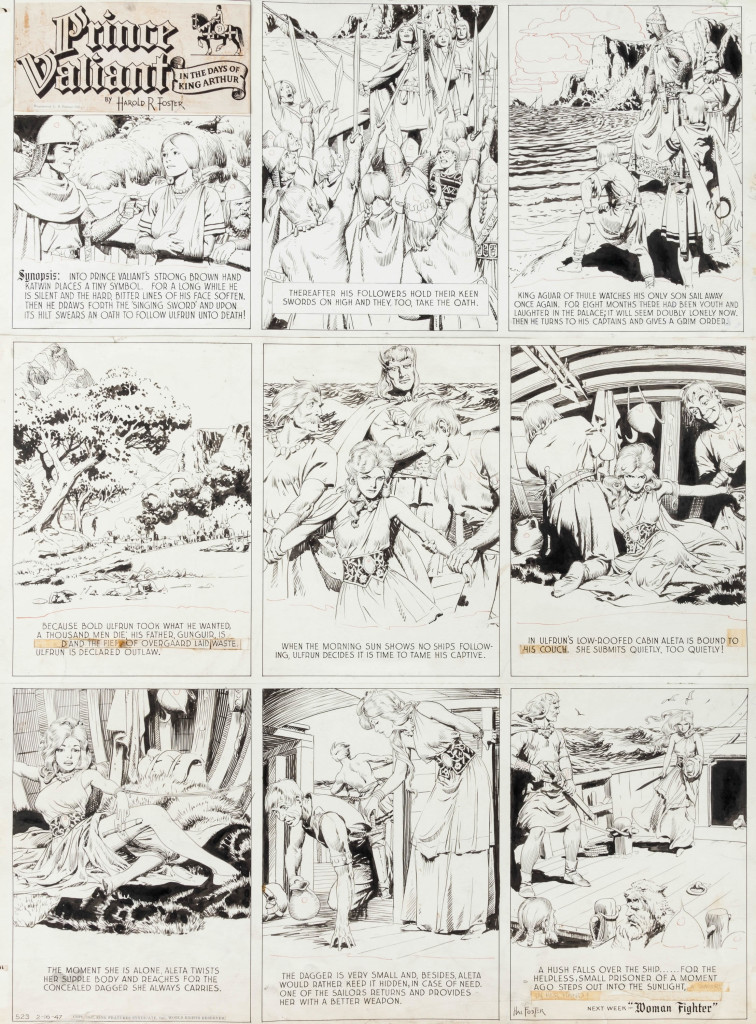

Hal Foster (1892-1982) created the epic adventure strip in 1936. He wrote and drew the Sunday-only saga until May 1971. The strip continues today by other artists.

“Foster drew about 1,760 Prince Valiant episodes, each a magnificent example of comic strip art,” says Joe Mannarino, director of comics and comic art at Heritage Auctions in New York. “He inspired artists like Wally Wood, Jack Kirby, Frank Frazetta, Al Williamson, Joe Kubert and Russ Manning. He was a legend who himself inspired legends.”

It’s widely acknowledged that Foster is among the “four pillars” of comic art, adds Nadia Mannarino, Heritage Auctions’ senior comics and comic art consignment director. “We’re talking Winsor McCay [Little Nemo], Alex Raymond [Flash Gordon], Milton Caniff [Terry and the Pirates] and Hal Foster,” Mannarino says. “Hal is regarded as the father of action-adventure cartooning, and his Sunday panels are considered the most beautiful illustrations ever done for the comics.”

The Intelligent Collector visited Tataranowicz (called “Tom T” by friends) to learn more about his Val collection.

How far does your collecting go back?

I was always kind of a collector. Kid stuff. Fossils, baseball cards and comic books. It was just plain fun back then, if even then already a bit obsessive. I would take a bus to downtown Detroit and could get a used comic for less than the original newsstand price, so it was easy. It was cheap. When I got into college and attending art school at Wayne State University – comic book inker Terry Austin was a classmate of mine – I started going to the early comic conventions. The Triple Fan Fair in Detroit was one of the first ones and had as guests Mike Kaluta, Barry Smith, Neal Adams, Jim Steranko, Jack Kirby, Russ Heath, Vaughn Bode, Jeff Jones – they were all there.

It was cool because it was small and you could go right up to the artist and they would do a sketch for you, and original artwork was for sale there. I looked around and said, “Wow, I can buy an original Deadman page from Strange Adventures No. 214 by Neal Adams for five to ten bucks or so.” Sadly, to this day, I harbor a deep regret of missing out on an original Barry Smith Conan cover featuring Elric of Melniboné because it was a whopping 50 bucks!

So I bought a whole bunch of original pages and as a college kid, I was thinking I was crazy because it was a lot of beer money to be spending at the time. [Laughs.]

And that led to Prince Valiant?

A few years later I moved to California and I’m really getting into Prince Valiant. I’d always liked it as a kid, and original pages were available. I had way more than enough of the comic book art, so I started turning those over into Prince Valiant pages. It was probably about 1978 while I was working on Ralph Bakshi’s Lord of the Rings. Ralph was also a big strip art collector. Looking at his collection and discussing it with him kicked me into collecting overdrive.

Where would you find this original Valiant art?

It wasn’t the heavy-duty competition for collectibles like it is now. Back then, collecting was a whole different thing. Somebody, maybe one of the handful of dealers around at the time such as Stu Reisbord or Jerry Mueller, would call you up and say, “Hey, I have a Prince Valiant from 1938. Do you want it?” You could take your time and think about it. At San Diego Comic Cons, [dealer] Russ Cochran would often be at a table with a beautiful Val sitting there. Day one of the convention, it would be there. Day four of the convention, it would still be there, and I would finally say, “OK, I’ll take it.” I might pick up a couple like that. At one point, I was – I’m sure it’s overstating it – but I think I was almost literally the only person seriously collecting Valiants in the world … [laughs] … because people just weren’t focused on it back then. Popular culture had not yet erupted like it did in the late 1980s.

Do you know where these pages were coming from?

There are all kinds of stories. When I started collecting, Hal Foster was still alive. It’s well known that if you donated money to some cartoonists’ fund, he would send you a page. And then at some point, he started cutting up panels and sending out individual panels if you wrote him a fan letter. There really wasn’t any after-market for this material. A lot of the Prince Valiants are personally dedicated by Foster. I have one that’s from 1941 that is dedicated to some guy he played golf with. So obviously he would just basically give them away. Of course, many comic artists also collected this strip. Al Williamson was obviously a tremendous collector. In the last few years, comic strip art has burst out into the mainstream and really has a much higher profile and a truly deserved appreciation for what it is.

What is it about Hal Foster’s art that makes it important?

One of the ongoing controversies about Prince Valiant and Hal Foster is whether it’s comic book art or illustration. In my opinion, it perfectly straddles the line in between. I think the strongest element about Foster was his unsurpassed skill at storytelling. If we had five days, I could give you a five-day lecture about the intricacies of his storytelling, how you could actually look at a Prince Valiant page, not read a single word and know exactly what the story was, what the people were thinking, their emotions and precisely what they were up to. The very best comic artists, in my view, create a real world that genuinely exists. Only several others come to mind, such as George Herriman, who did Krazy Kat. He created a world that, as odd as it is, made you feel it genuinely existed. You knew this world. Walt Kelly, with Pogo, created a world that really existed. And Hal Foster accomplished the same thing. Prince Valiant was a real world with real characters. It was the chronicle of a real – even if fictional – life, with action, romance, family and humor and wasn’t simply just an adventure story of superficial heroic posturing.

A second facet of Foster’s art that appealed to me was his obvious dedication. He had the perfect job in the whole world for a comic strip artist. He created the strip, he drew it, he wrote it, he handled the coloring, he did only a Sunday a week, was totally focused on that and he became famous for it. A lot of other artists also did advertising work. They did this, they did that, they did dailies, they did a whole bunch of other work. As a result, much of their strip work didn’t have the same in-depth integrity and total realization of content that Foster put into his work. And that’s probably why Foster’s work endures. People look at it and in a visceral and even subconscious manner, they can pick up on that aspect after all this time – even though it’s from a different time period entirely.

And he was an exceptional artist …

Hal Foster was undeniably a superb draftsman with an impeccable sense of perspective and anatomy. Subtle and sensitive drawing. Spot-on staging with a stunning sense of locale. Incredible rendering of texture and detail. A classical line with a loose, agitated line used when needed for high emotion or action, all with a sure aesthetic knowledge and instinct of what details to draw and what to leave out. Some other artists, such as Alex Raymond, may have in some ways been more natural and certainly slicker artists. Raymond, for one, was capable of doing almost painfully beautiful drawings, but as the complete package, Foster cannot be beaten, in my opinion. In this medium, it is ultimately all about telling the story. As comic book legend Gil Kane once said – and I paraphrase – “For every road you are going down as an artist, Hal Foster has already been there.”

Did you have goals with your collection?

I focused on collecting premier pages from each time period, beginning with 1937, the first year of the strip. As Foster’s style continuously and perceptively evolved in subtle ways not only from decade to decade, but from year to year, my goal was to have one solid example from every year. That goal of mine was easier said than done. The problem is not so much the logistics of getting strips, but that some just don’t exist for the getting. My understanding is Syracuse University has practically one entire year, 1952, so they’re really not many of those available. And then there are the possibly apocryphal stories of so much of the strip art being trashed by the syndicates. Cut up and destroyed. Luckily, there are also stories of the “dumpster diving” exploits of early collectors.

So what was your collecting focus?

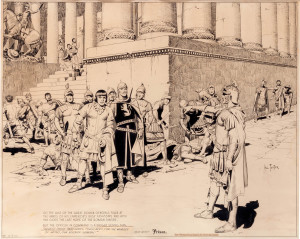

It was far from a numbers game for me. Other than my “completist bug,” I’ve tried to focus on a number of the varied aspects that exemplified the strip. I wanted examples of key periods in Val’s life, and also elements that [reflect] Foster’s various strengths. For example, I wanted a really good horse page, because he really excelled at drawing horses. I wanted a really great Aleta [Valiant’s wife] page, so I have a number of those because there are just a whole lot of good ones, and one example just never cut it. And then I wanted representations of Val in different manifestations of himself. For example, we all know what Prince Valiant looked like. He had that page-boy haircut, but sometimes he cut his hair short. Once, his hair got burnt off. Sometimes he grew a beard. One time, he went to Rome so he cut his hair in a curly Roman style and dressed like a Roman senator, and I wanted an example from that. Then, of course, there were collecting examples of key characters: Gawain, Tristam, Arthur, Merlin, Lancelot, Arn, the Val twins … it goes on and on. Collecting can be something of a sickness. An enjoyable and hopefully controllable one, but a sickness nonetheless. You’ve just got to kind of roll with it.

I see Foster’s art on your walls. His pieces are huge!

Another element Foster was famous for, oh, maybe twice a year on average, he did a page that had a big panel. I mean huge. Sometimes half of the entire Sunday page. Genuine artistic tour de forces. When people first see any original Valiant pages, they’re blown away by how big they are, approximately 2 by 3 feet. Really big! And then imagine two thirds of that being one panel. And so these pages are always the crème de la crème for collectors. It looks big and it looks great. I was able to focus on getting some of those.

You acquired your first Prince Valiant in …

About 1978. It was a page from 1966 and featured Arn in the New World. No Val or Aleta, but a nice page with an actual panel cut from a 1947 “Val in the New World” page that Foster re-used as the last panel in 1966. It wasn’t my “perfect” page, but it was a start. At least I had an original and went from there.

Are you still collecting Prince Valiants?

I’m still looking. What’s sadder than a completed collection, right? Remember the whole sickness thing?

A few months back, Heritage Auctions had an outstanding Valiant, a big panel from 1946. It was the wedding of Aleta and Val. Well, 10 years ago, I would have been all over that. I don’t think anybody would have gotten that but me. But now, I’m at the point where my thinking is, “Well, I have something from that year.” My loss maybe, but lucky for other collectors now entering the field. I have a decent-size house, but I still can’t begin to hang up my entire collection. I don’t want to have them just stacked in the closet somewhere. So I’m thinking, “OK, I should start getting them out there.” But also, I really, truly believe I’m not really the owner, but a steward of these pieces, and they should be enjoyed by as many people as possible.

In fact, people are starting to put them in museums, and maybe that’s where many of them ultimately belong. It is well known that Europe has been far ahead in their appreciation of comic strip art as a legitimate art form. However, I’m sensing that the U.S. is now catching up in this regard. I believe this is happening more rapidly as serious collectors are realizing the true aesthetic value of seminal comic strip art of such high quality. It seems a lot of collectors are beginning to seek out the classic Prince Valiants, Flash Gordons and Krazy Kats. They are truly beautiful and historic works, and belong in any serious comic art collection.