DAVID LEVINTHAL’S FAMED PHOTOGRAPH SERIES CELEBRATES AN AMERICAN DOLL THAT IS ONE PART TOY AND ONE PART CULTURAL ICON

By Christina Rees

The work of American artist David Levinthal has for decades exposed the longing, pleasure, regret and anxiety that we strange human animals pack into small things that are stand-ins for our biggest moves and mythologies. In Levinthal’s world, our toy cowboys and soldiers, our Barbie dolls, our tiny sentimental figurines of athletes and astronauts take star turns in his photos of heroic spectacle that look like stills from John Ford epics, Stanley Kubrick odysseys and Michael Mann thrillers.

Levinthal’s photographed scenes of these playthings and miniatures, which he calls to action in color-saturated tableaux, vibrate off his picture planes like grand old cinema or giant billboard ads that channel our own sex- and violence-addled brains. The fashion for illuminating the grown-up psychological complexity imbued in objects made for children’s play (or other innocent endeavors) isn’t new, but on the art photography end, Levinthal pretty much started it back in the early 1970s with his seminal series Hitler Moves East, which sets tiny model soldiers into blurry and blighted hellscapes of a war front that could pass for stills from Ric Burns’ bleakest World War II documentary.

Ever since that early series caught traction in the art world, Levinthal’s visual presence and influence in our pop culture has been quietly ubiquitous; not only are his bodies of work some of the most widely exhibited and distributed of our contemporary American artists, but the very trope of seeing our childhood toys (and memories) reintroduced as provocative social commentary is pure Levinthal.

“Toys have often been a casual way to not think about ‘the horrors,’” Levinthal says. “But they’re a powerful form of socialization, and we’re more cognizant of that now.”

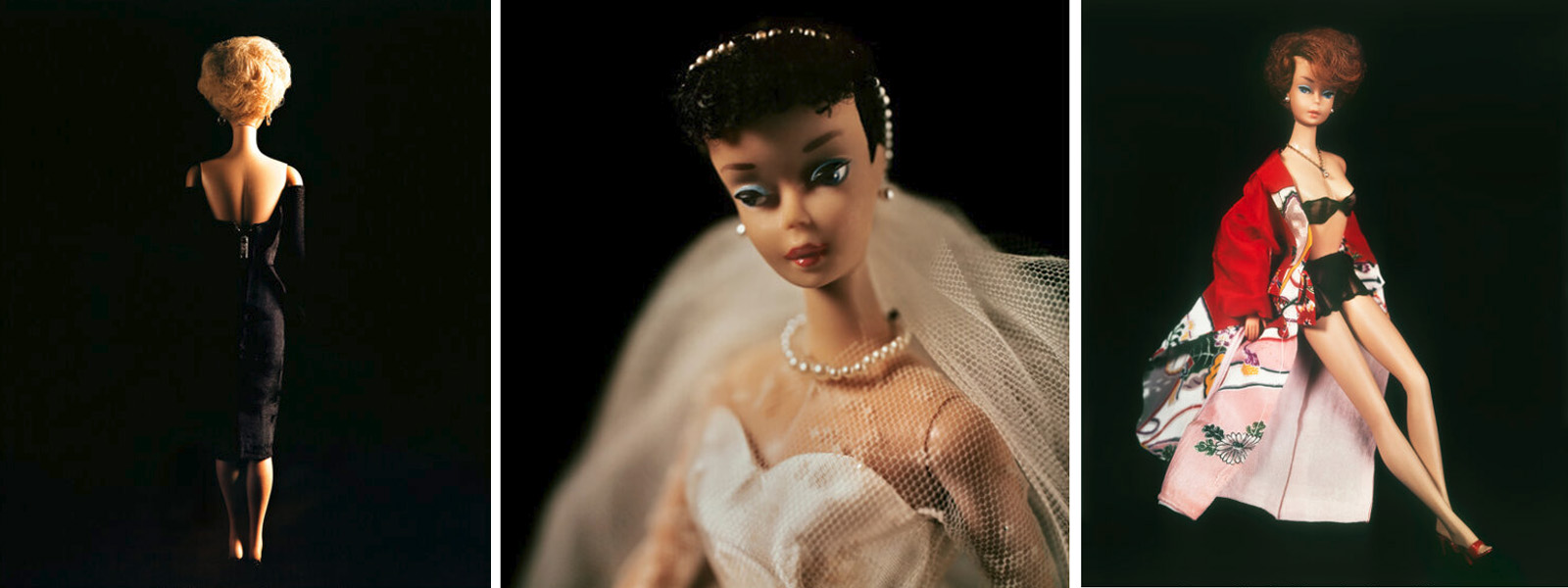

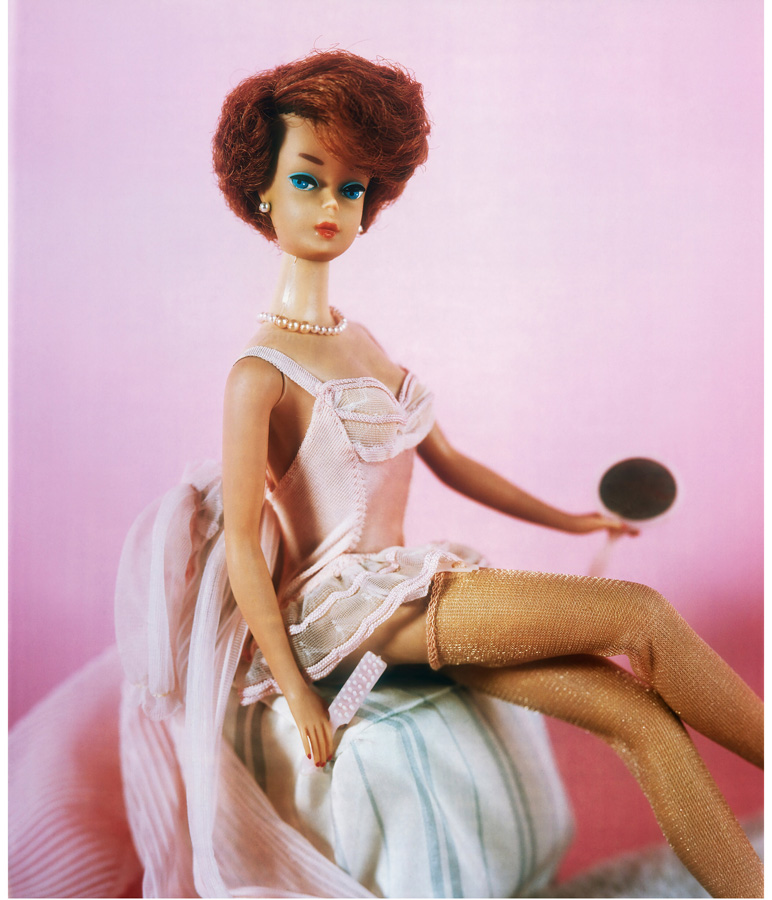

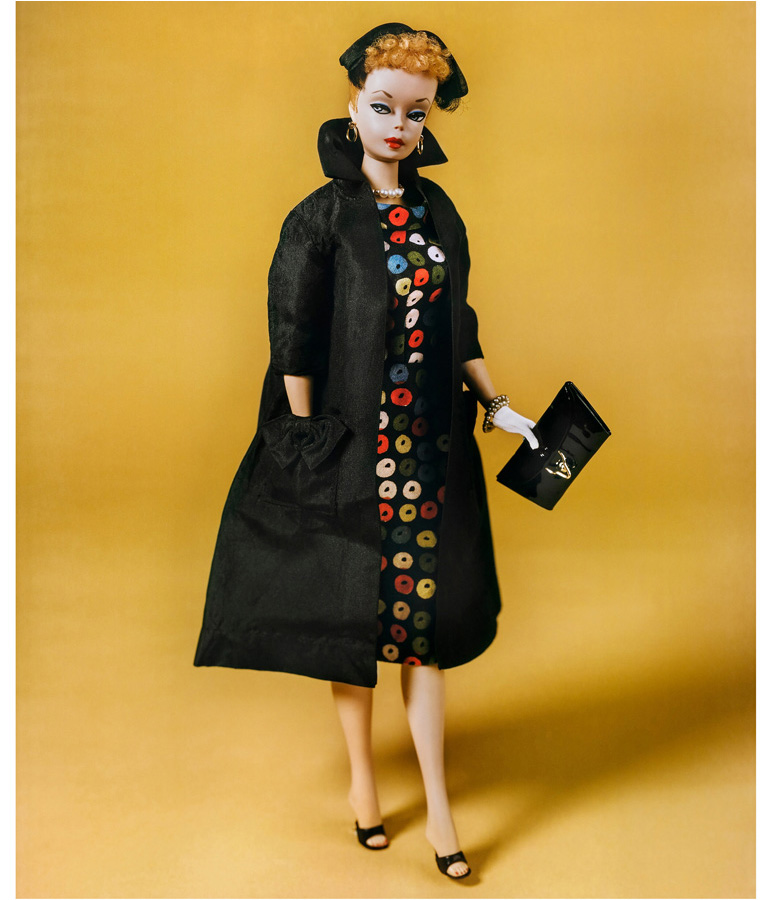

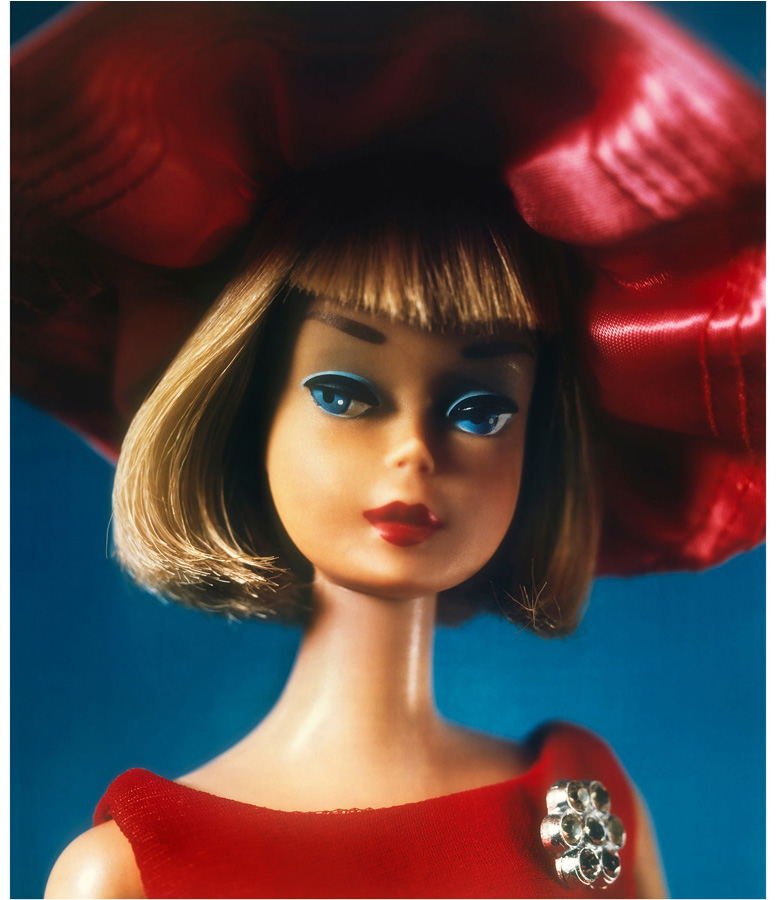

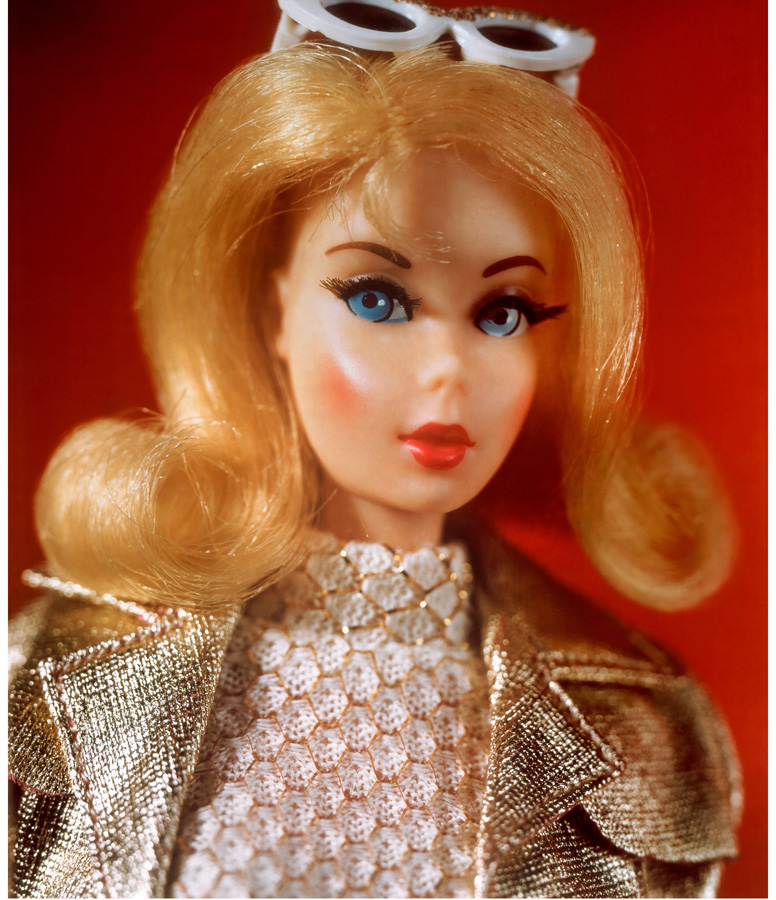

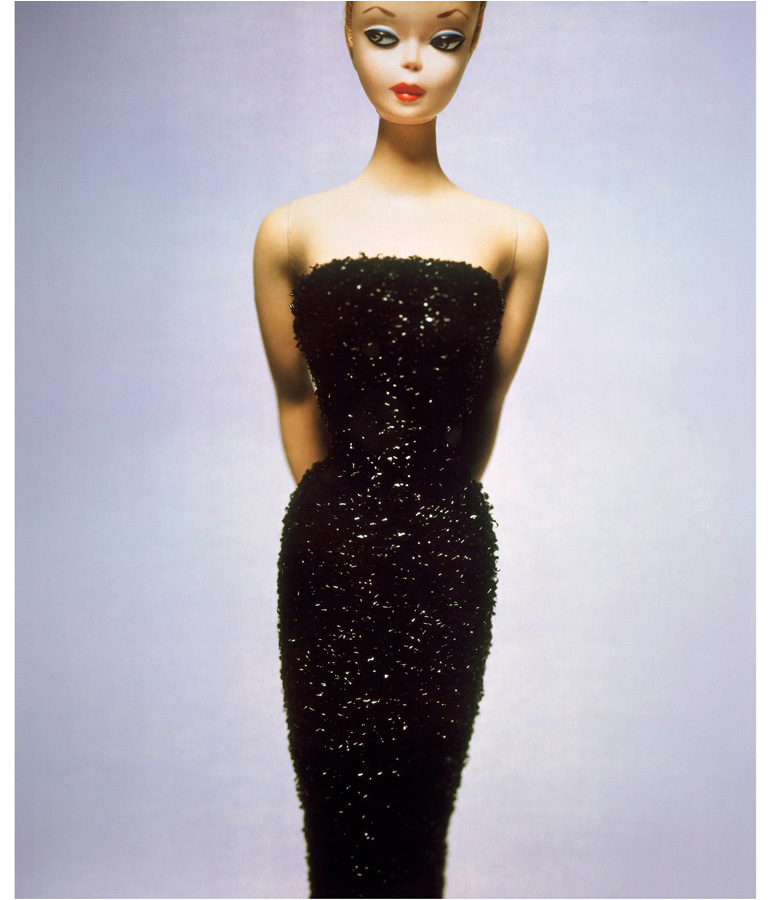

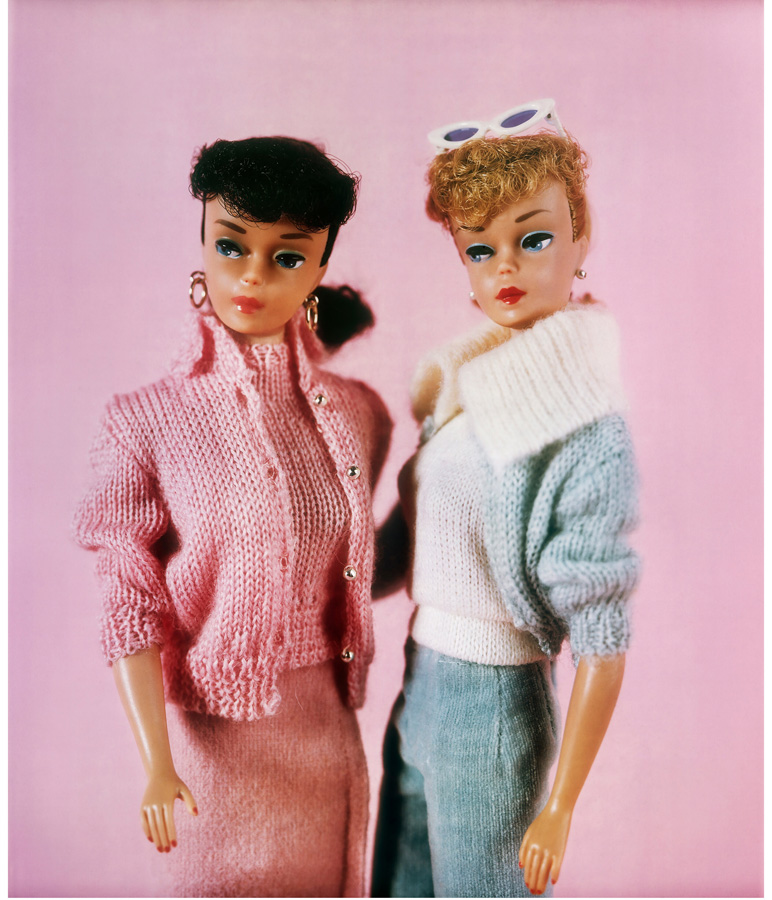

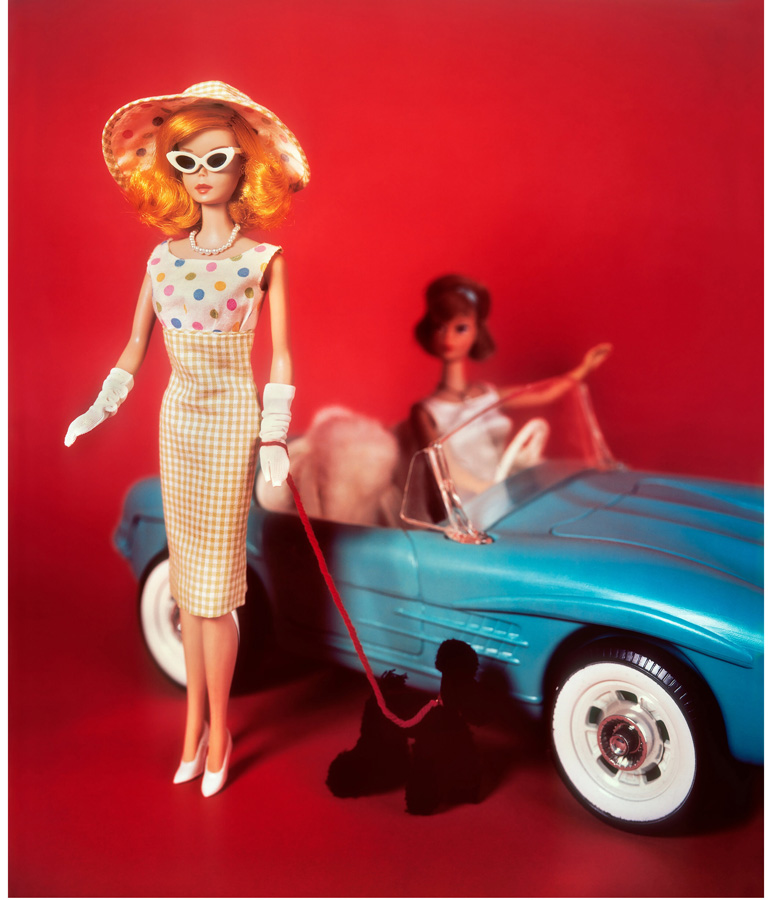

Levinthal’s second outing with Mattel’s doll Barbie, for his 1997-98 series titled simply Barbie, took place for the doll’s 40th birthday and called upon the artist to reimagine his usual action-heavy scenarios instead as a studio shoot for a magazine editorial, a la Irving Penn or Richard Avedon. In Levinthal’s rendition, Barbie is centered, staged, lighted and costumed as though posing in a Dior number for a spread in Diana Vreeland’s Vogue. The large-format portraits are searingly detailed and confrontational – Levinthal’s extreme focus on Barbie’s delicately painted face (blue eye shadow, glossy mouth) and the cuts and textures of her old-Hollywood wardrobe (the strapless LBD; the pink nubby twin set) produces a push-pull of familiarity, wonder and a hint of apprehension, and it’s a sense Levinthal shares, though in a way he appreciates.

“I was going for that early ’60s feel – for the way she had been projected in TV ads,” Levinthal says. “And what I realized in the process is that you can’t abstract Barbie.”

Indeed, we have asked too much of this doll, and she has more than delivered. Now, as we celebrate Barbara Millicent Roberts’ 65th birthday with a blockbuster feature film about her and oceans of press ink spilled about what it all means, Heritage offers Levinthal’s iconic Barbie series to a new generation of collectors. Bidding on Heritage’s March 23 Barbie by David Levinthal Photographs Auction begins March 9 at the Motion Picture & Television Fund’s “Night Before” the Oscars event in Los Angeles. The evening also marks Barbie’s official birthday. Proceeds will benefit MPTF, a charitable organization that offers financial assistance, case management and residential living to those in the industry with limited resources.

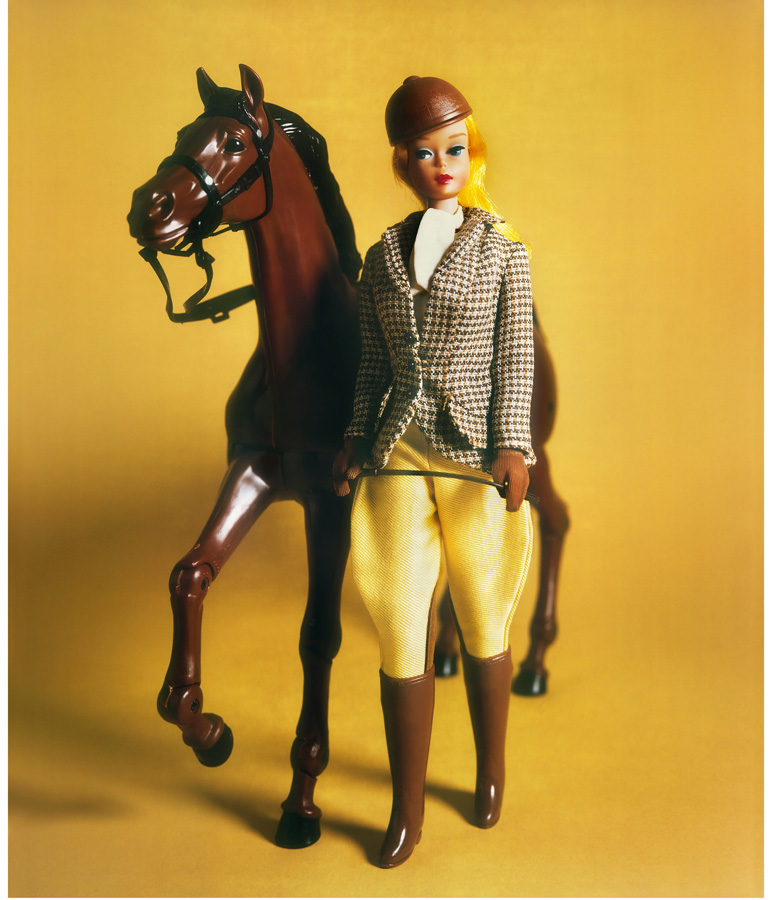

The edition of this set of photographs is exclusive to Heritage, and the 28 Barbie portraits from the iconic series include the winsome protagonist in her various guises: as an equestrian, a bride, a shopper, an all-around glamour puss. Barbie wears lingerie and bathing suits, dons a fur stole, walks her poodle. The highlight of the auction is a lot of the complete portfolio – a set of all 80 photographs – for which Levinthal has created a one-off pink box that makes it a true collector’s item.

The narrowness of Barbie’s purpose is rivaled only by the completeness of her femininity. Like Levinthal’s toy soldiers and cowboys, unable to escape the epic brutality of their appointed roles, Barbie occupies her lane with weary authority. We realize, as we attempt to catch the doll’s darting eyes – which Levinthal has so cleverly blown up and put at our own eye level – that we are too invested in her image to permit anything less.

“Ruth Handler was a genius,” Levinthal says of Barbie’s beloved creator. “She realized at the time that girls were limited to baby dolls and things that only helped them prepare for one kind of life. She wanted them to know there was so much more – and Barbie could be a way for future roles to be projected.”

A useful tool to prepare for adult life, yes. But to complicate things, Levinthal’s work also reflects back at us those projections and preoccupations we force onto our symbols and motifs (and toys) and thus shows us both how ambitious and brittle our sense of self can be and how our role in the world is so often decided for us. The rich emotional scenes set up by Levinthal, with their weight of historic moments that force us into action, are imbued with a timelessness we recognize to be a hallmark of not just great art, but also our favorite art. Much like Barbie, Levinthal is an American treasure.

CHRISTINA REES is a staff writer at Intelligent Collector.

CHRISTINA REES is a staff writer at Intelligent Collector.