MOVIE PRODUCER SEAN SORENSEN AMONG THE GROUNDBREAKERS IN EMERGING ‘URBAN ART’ MARKET

By Stacy Suaya

Portrait by Axel Koester

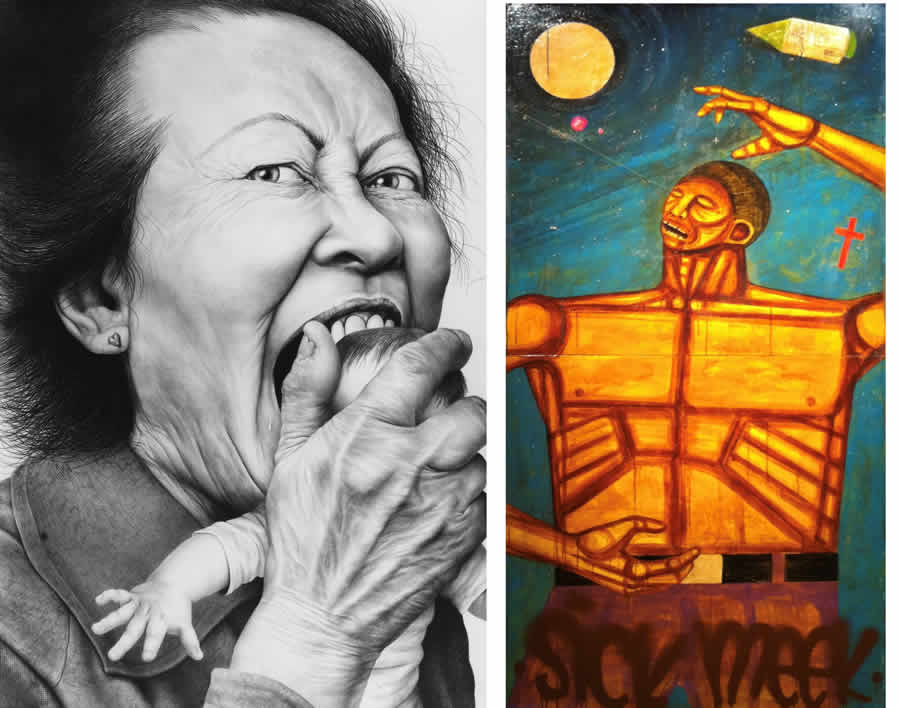

If you happen to be an Airbnb guest at Sean Sorensen’s home in the Inglewood neighborhood of Los Angeles, you may find yourself waking up to a large, original drawing that depicts a woman about to bite into what could be a big, juicy apple.

INQUIRIES

URBAN ART & COLLECTIBLES FINE ART AUCTIONS

Leon Benrimon

214.409.1799

LeonB@HA.com

But look closer.

It’s actually the head of a baby.

The disturbing piece is Love Bite by L.A.-based artist Laurie Lipton, whose work has been described as a mesmerizing blend of scale and detail, horror and humor, fantasy and reality.

In the art-filled home of Sorensen, a screenwriter, producer and founder of Royal Viking Entertainment, you will also find paintings by John Wayne Gacy – yes, the serial killer – and a human-size sculpture of street artist Shepard Fairey by Ryan McCann of Fairey being crucified. “I think the common denominator,” Sorensen says of his collection, “is you don’t have to love it and you don’t have to hate it, but you can’t ignore it.”

Enlarge

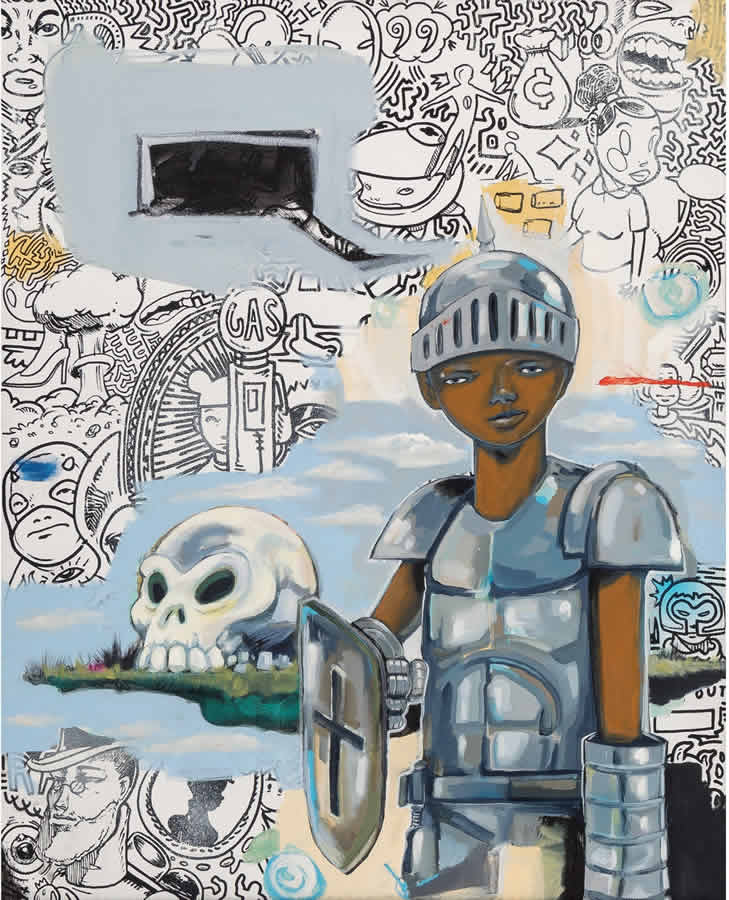

Sorensen is among a growing number of collectors who’ve expanded from being “street” or “urban” art collectors to the world of contemporary art. Urban Art is a category gaining popularity in the auction world and among collectors, but which is still being defined by people like Sorensen.

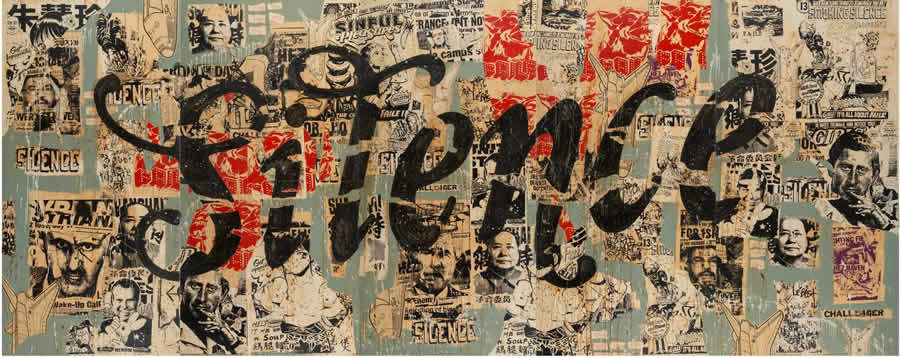

Generally, Graffiti Art refers to graffiti artists, sometimes called “writers,” who use city environments to get their message out (as opposed to a traditional art gallery), and pieces that reference ideas or subject matter that represent the culture-at-large at the moment. “The category traces back to New York City in the 1970s, with artists like Keith Haring,” says Leon Benrimon at Heritage Auctions. “Three popular examples today would be Banksy, Shepard Fairey and Brian Donnelly, known professionally as KAWS.” Works by these artists often sell in the high six figures.

The category can also include collectible multiples popular in big-city youth culture, such as toys, footwear, skateboard decks and even surfboards by brands such as Supreme, Be@rbrick, BAPE and Kidrobot. A pair of Nike Air Mag (Back to the Future) sneakers, in their original box with a numbered plate signed by designer Tinker Hatfield, sold for $44,000 at a June 2017 auction, and a pair of Pharrell’s Adidas “Human Race” sneakers, designed especially for friends and family, sold at a charity auction for nearly $7,200. A set of three, signed 7-inch KAWS figures from a 1999 edition of 500 produced by Bounty Hunter, Japan, sold for $36,648.

Enlarge

“The collector base for Urban Art is generally millennials, who are excited because it’s one of the few collecting categories that has been able to captivate them,” Benrimon says. Collectors like Sorensen represent a “changing of the guard,” Benrimon adds. “We’re seeing a wave of millennials that have enough financial success to drive the market.”

Heritage Auctions launched its Urban Art category in 2017 and now holds two Signature® Urban Art auctions a year, and nearly a dozen online-only auctions.

Enlarge

Sorensen’s interest in untraditional or politically charged art stems from his own years as an artist.

In Chicago in the early 2000s, he once staged a public street parade of volunteers in burqas – not just any burqas though, but ones printed with logos like Starbucks and Shell Oil. “I embrace polemic ideas,” he says. Back then, he was a writer for the satirical fashion and culture magazine Flaunt, and sold his first movie idea and signed on to write and executive produce it with Warner Bros. He had plans to be a Renaissance man – until he realized he didn’t have the bandwidth for it all. The things he couldn’t live without were movies and television, so he decided to focus full-time on making the two (“The kind you can’t ignore,” he says, naturally).

He replaced making art with collecting it.

Among his first art purchases were an early Jeff Gillette piece, depicting an impoverished shantytown with a McDonald’s in it, and another Gillette, of the Disneyland sign amidst a horizon of total devastation; some letters have fallen off, leaving “Died.” Around that time, Sorensen ran the film division at Motion Theory Films, housed in an airplane hangar in Marina Del Rey, Calif. He was there for seven years, filling the hangar with art. “I collected to the size of the building, basically,” he says.

Enlarge

Just as Sorensen connected with Love Bite – after a difficult childhood, he says he knows what it feels like – another favorite, sentimental piece of his is Star Gazer, an 8-by-5-foot acrylic and mixed media piece by a collaboration of artists known as the Date Farmers. As a boy, he and his grandfather would look at the planets through a telescope, and when he sees this piece, he feels it’s a way to connect with his grandfather.

Another beloved work is a birthday card made just for him by British visual artist David Shrigley. A former girlfriend – knowing of Sorensen’s respect for Shrigley – reached out to the artist and asked if he would do it. When Shrigley agreed, Sorensen was so impressed that he got back together with her.

“Rule number one is buy what you love,” Sorensen says. He loves the reactions he gets from the pieces he buys, particularly from Love Bite, which measures 72 by 59 inches. It used to hang in his Motion Theory office, Sorensen says, and 10 percent of the people who saw it thought it was the most amazing thing they had ever seen. For another 10 percent, it was the most horrific.

Sorensen admits he’s not interested in the other 80 percent. He’ll just continue gravitating toward non-traditional art that stops him in his tracks. Meanwhile, he says his Airbnb guests go out of their way to say how much they love his art. “Now, if I could only get Laurie Lipton to make a cookbook.”

Enlarge

Enlarge

STACY SUAYA is a Los Angeles writer who has written for T: The New York Times Style Magazine and the Los Angeles Times. This story appears in the Fall 2018 edition of The Intelligent Collector magazine. Click here to subscribe.

STACY SUAYA is a Los Angeles writer who has written for T: The New York Times Style Magazine and the Los Angeles Times. This story appears in the Fall 2018 edition of The Intelligent Collector magazine. Click here to subscribe.