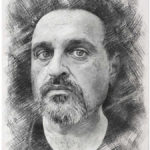

FILM PRODUCER MIKE GLAD HAS AMASSED ORIGINAL ART BY SOME OF THE FIELD’S GREATEST CREATORS. NOW IT’S HEADING TO AUCTION.

By Steffan Chirazi • Portrait by Scott McCue

When he was a kid, Mike Glad collected stamps, but he never had enough money to specialize. “I had a world collection,” the collector, photographer and Oscar-nominated film producer says with a laugh from his Modesto, Calif., home.

EVENT

THE ART OF ANIME SIGNATURE® AUCTION 7254

Featuring the Mike Glad Anime Museum Collection

June 25 -27, 2021

Online: HA.com/7254a

INQUIRIES

Jim Lentz

214.409.1991

JimL@HA.com

“You could buy 500 different worldwide stamps for two dollars. You’d then go home, spread them out on a table and start looking through your stamp album. When you found a picture of one of these stamps in your album, you got excited. It was a very, very wonderful moment.” Mike is remembering his earliest forays into the world of collecting, one which has seen him ascend from a youthful enthusiast to a collector recognized as having the most comprehensive collection of animation art in the world.

It’s his Japanese animation collection that will receive the plaudits at Heritage Auctions’ animation art auction scheduled for June 25-27, 2021, and thus it is the focus of our discussion.

“The Glad Anime Museum Collection, which has traveled from museum to museum globally, is one of the single most important anime animation art collections ever brought to market” says Jim Lentz, animation art specialist at Heritage Auctions. “I have never seen so many A-plus titles/properties with so many A-plus images ever assembled in one collection. We expect some genuine global excitement once these images are shown to the world.”

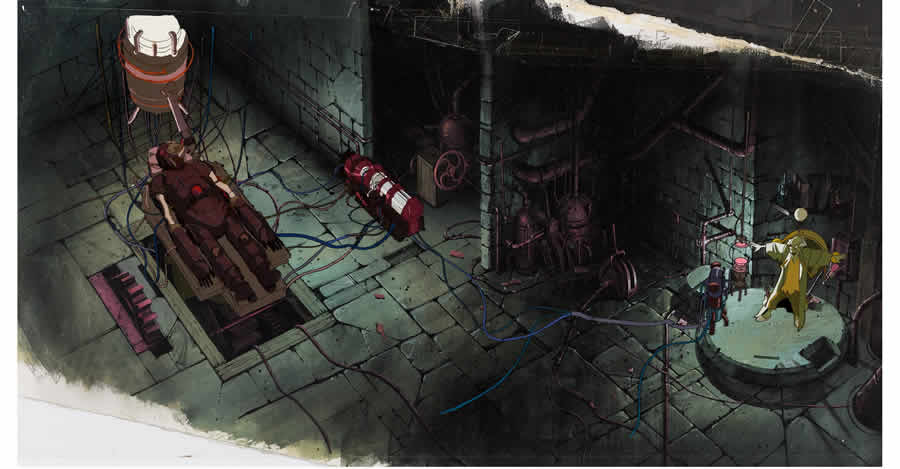

Enlarge

Kaneda Motorcycle Production Cel sequence on Key Master Background

Estimate: $10,000-$15,000

The Mike Glad anime collection first began back in 1988. Hungarian animator and studio owner John Halas had organized a traveling art show called “Masters of Animation,” based around his book of the same name. Glad and his wife Jeanne had dinner with Halas. Glad asked Halas whether he would share the addresses for all the principal animators in his book, and Halas remarkably agreed. Glad then wrote to all the animators asking for definitive samples of their work. One of those who replied was Osamu Tezuka (1928-1989), the celebrated artist, cartoonist and animator today known as “the Father of Manga.”

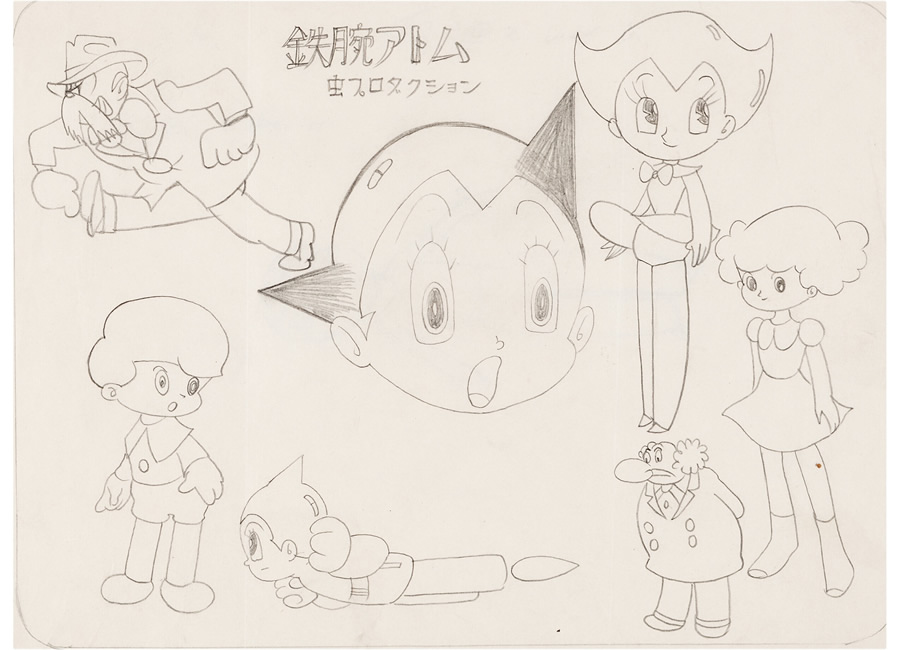

Enlarge

Original Astro Boy Model sheet attributed to Osamu Tezuka

Estimate: $7,500-$10,000

“Ultimately, he sent me two Astro Boy pieces and a Phoenix piece. His artwork made me curious about the ignored anime,” explains Glad. “In the late 1980s, the major production houses in the United States had no interest in distributing or dubbing anime films, period. The late Carl Macek, producer of the animated TV series Robotech, considered a real touchstone for anime’s fandom in North America, and Jerry Beck, a prominent American animation historian, formed the company Streamline Pictures and signed a domestic deal to produce Akira, the smash hit in Japan.”

During this process, Beck thought it would be interesting to have an Akira cell on their office wall, and reached out to the original Japanese production company. “They told him they had all of the Akira production materials and it was about to be destroyed,” Glad recalls. “Due to his initiative, Streamline received all the cels, backgrounds and production notes on Akira for the cost of shipping. Later, Beck complained about his effort moving heavy boxes upstairs from the street to their office. What? When he opened the boxes, he discovered some of the amazing pan backgrounds were packing materials! Incredible.”

Glad is clear as to what anime art adds to a collector’s arsenal.

“There’s the whole rich history of manga art, and the aesthetics of a Japanese cartoons are distinct,” he says. “When you see a Japanese anime character, you know that it’s anime. There’s no wondering whether Speed Racer came from Japan. You’re not going to see Snow White running around like Sailor Moon. This work broadens your collecting to a world far different than U.S. animation. Bright colors that pop envelope the young, yet the target audience is often adults. Life doesn’t always have a happy ending.”

Glad feels there is an indelible connection between the darker elements of modern Japanese history and the whole anime aesthetic.

“Often, there’s a correlation between the work and World War II, with Hiroshima and Nagasaki,” he sighs. “Many of the writers and artists of anime were adults when the bombs dropped. This destructive power had a tremendous influence leading to another common anime theme, which is World War III. In the story, this conflict has often just ended and left a post-apocalyptic environment that is wholly engaging and visually unique. Anime is also concerned with technology and its interaction with humans. Thus, a film like Robot Carnival, an anime Fantasia, gets made.

Enlarge

Production Cel on Key Master Background

Estimate: $5,000-$7,500

Enlarge

Production Cel on Pan Key Master Background

Estimate: $2,500-$5,000

“But when it comes to the biggest cultural influence on anime,” Glad adds, “that has to be manga. Since the 12th century, the Japanese have been absorbing multiple images telling a story. Historically, many Japanese adults have read manga on the subway going to work.”

Anime’s incredible success as an artform explains why Glad’s pieces have been exhibited in museums worldwide – including the German Film Museum in Frankfurt, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences in Beverly Hills, the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art in Denmark, the Museum of Fine Arts in Belgium, and Bonn Museum of Modern Art in Germany.

Asking Glad to call out the definitive characters and pieces in his collection verges on a fool’s errand given its vast scope. However, there are some key pieces to know about.

Enlarge

Miyazaki Production Cel on Key Master Background

Estimate: $5,000-$7,500

Enlarge

Gohan Production Cel on Master background

Estimate: $2,500-$5,000

“If you’re collecting Astro Boy, there are a number of things that you might consider. Perhaps you want him flying or a black-and-white setup. You establish your criteria and then find artwork that will meet your needs. Personally, I love anything with Astro Boy.

“Another favorite of mine is Dragon Ball Z. I like one image particularly because of the exploding background, which illustrates the explosive nature of the character. There’s also Pokémon. Pikachu is riding in front. I don’t think the image can be topped.”

It is obviously going to be hard for Glad to give up the entire collection for auction, yet he has agreed to do exactly that.

Enlarge

Production Cel on Master Background

Estimate: $2,500-$5,000

“I wish I’d said I’m keeping five or six pieces, but I overlooked that scenario and made a commitment. I believe there are nearly 200 pieces, and I’ve told you about a couple of my favorites. Here’s another one I think is just fantastic. It’s a cel and background from a film called The Castle of Cagliostro, which was directed by [Hayao] Miyazaki before he had Studio Ghibli. You won’t find another image as dramatic with Lupin the principal character. You just cannot find anything like it. Did I mention the Catbus cel from My Neighbor Totoro or the [Katsuhiro] Otomo pencil drawing from the Robot Carnival end credits. Do I have to stop?”

Glad smiles warmly, a man filled with equal measures of pride and affection for his collection, knowing that there are going to be some collectors out there feeling the same joy he has felt in acquiring these works.

STEFFAN CHIRAZI is a Bay Area author whose work has appeared in a variety of international publications, including the Metallica Club’s So What! magazine, the San Francisco Chronicle and Kerrang!

STEFFAN CHIRAZI is a Bay Area author whose work has appeared in a variety of international publications, including the Metallica Club’s So What! magazine, the San Francisco Chronicle and Kerrang!

This article appears in the Spring 2021 edition of The Intelligent Collector magazine.