JERSEYS, BASEBALLS, AWARDS AND MORE FROM ‘MR. TIGER’ HIMSELF

By Robert Wilonsky

EVENT

FALL SPORTS COLLECTIBLES CATALOG AUCTION 50049

Nov. 18-20, 2021

Online: HA.com/50049

INQUIRIES

Chris Ivy

214.409.1319

CIvy@HA.com

The Detroit Tigers’ Al Kaline “led by the way he played,” George Cantor wrote in his book The Tigers of ’68: Baseball’s Last Real Champions. To put it simply, the Hall of Fame outfielder with the strong arm and the big stick was better than most who played the game, before or since. A man whose “skill level is unattainable to most others,” wrote Cantor, who covered the Detroit Tigers for the Detroit Free Press during its mythical ascension to World Champions during that tumultuous year marked by the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. and the riots that followed.

“You hear about him, sure, but you can’t really understand until you see him,” pitcher Johnny Podres told Cantor about Kaline, who played all 22 of his pro-ball seasons in Detroit and remained with the club as broadcaster and front-office special assistant. Kaline, Podres said, “just never makes mistakes.”

Hence his 10 Gold Glove Awards. His 18 trips to Major League Baseball’s All-Star Game. His American League batting title in 1955. His Roberto Clemente Award in 1973 (he was that award’s very first recipient). That World Series ring in ’68.

And that first-ballot induction into Baseball’s Hall of Fame in 1980. And that retired number, 6. And that nickname, “Mr. Tiger.”

“All those awards were about one thing: the work ethic,” says Mark Kaline, one of Al’s two sons. “It was about commitment to hard work. I can remember Dad saying, ‘Whatever you do, be the best at it.’ In his case that meant: Be the first guy in to take batting practice or shag balls. Become an expert at your craft, whatever that may be. Those are the life lessons.

“The awards were emblematic of the hard work and dedication he had to being his best. He never professed to being the best. He was very flattered by a lot of the awards. But he would tell you many times he was a far better defensive player than offensive one, even though he had 3,007 hits and 399 home runs. He said that even when you’re 0-4 at the plate you can contribute to the team by keeping a guy from going to second on a ball hit into ‘Kaline’s Corner.’ It was that attention to detail he put into his craft.”

In November, Heritage Auctions celebrates that extraordinary craft behind that Hall of Fame career by offering more than 400 items from The Al Kaline Collection, ranging from the World Series Championship Trophy presented to members of the ’68 team in 2018 to his Gold Glove awards to his home-run and career-hit balls and game-used jerseys and bats to the golf bags and clubs that were his constant companions at the famed Oakland Hills Country Club.

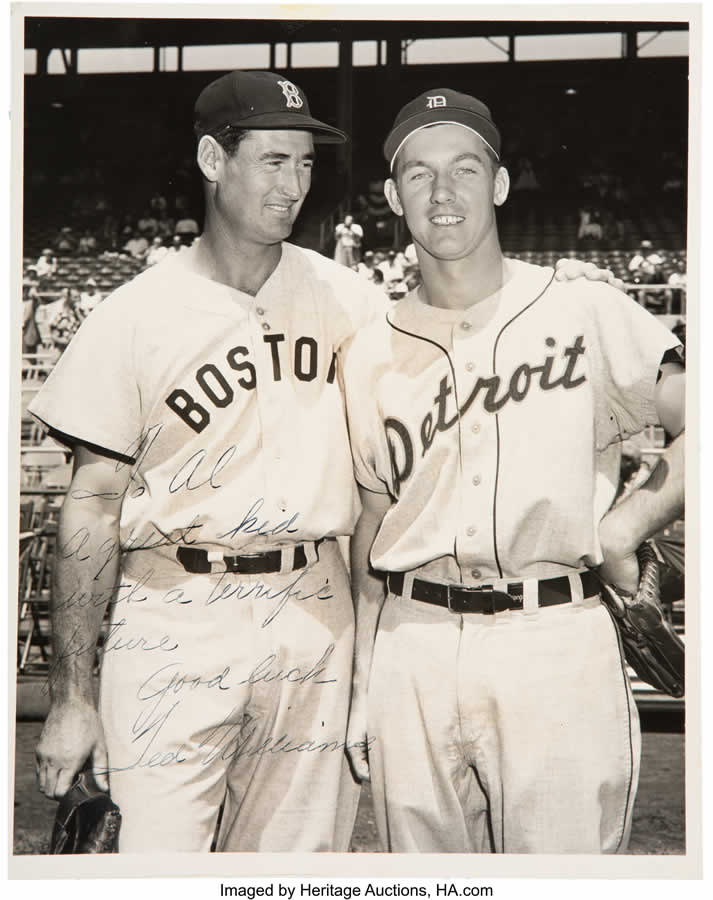

Here, too, are baseballs signed by the Tigers teams on which Kaline played, as well as ones signed by the fellow All-Stars with whom he shared the field throughout his Hall of Fame career. It’s clear Kaline treasured these balls, among them ones signed by Babe Ruth and Ty Cobb, Hank Greenberg, Ted Williams, Stan Musial, Bob Gibson and other fellow legends. Each is in superb condition, an object of attention and affection.

Those items, along with his 1980 Babe Ruth Crown Award and several American League, All-Star Game and World Series championship rings given Mr. Tiger over the years, serve as a centerpiece of Heritage Auctions’ Nov. 18-20 Fall Sports Collectibles Catalog Auction.

“Heritage Auctions has long been where baseball legends and their families have come to share their collections with the fans, including Stan Musial, Brooks Robinson, Willie McCovey and, in this upcoming auction, St. Louis Cardinals great Lou Brock,” says Chris Ivy, founder and president of Heritage Sports. “It’s an honor to add Mr. Tiger to that estimable list with an auction that offers a veritable history of the game he loved so much that he remained a part of it for his entire life.”

That history includes a photo of Ted Williams and Babe Ruth, signed by Williams to Kaline. The inscription says all one needs to know about Mr. Tiger: “To Al Kaline, who can be as good as anyone.”

Upon Kaline’s death last year, at the age of 85, he was endlessly called “a titan” and “a legend,” befitting his stature in the sport he began playing professionally at 18 — right out of high school in Baltimore, without a second spent in the minors. As longtime Detroit Free Press beat writer John Lowe wrote upon Kaline’s death, he “embodied the beauty of the game and became a living monument of how gracefully it could be played.”

Lowe reminds that Kaline was shocked when he was elected to baseball’s Hall of Fame in 1980. Only nine players before him had been put in Cooperstown on the first ballot, among them men named Mays, Mantle, Musial and Jackie Robinson. He was No. 10. He honestly did not believe he belonged among such giants, just as he didn’t believe he belonged in the Tigers’ starting lineup for the 1968 World Series, as he’d sat out some of that season with an injury.

“He always felt blessed to make a living playing the game he loved,” Mark Kaline says. “He looked at his parents and how they worked so hard so he could play baseball. He played on three sandlot teams in the summer when he was a kid. He would change uniforms in the car on the way from game to game. And he never lost sight of that.”

Kaline felt so fortunate to play the game he never demanded it pay him a penny more than he felt he deserved. In fact, shortly after the end of the 1970 season, Kaline rejected the Tigers’ offer of a $100,000 contract — the first in team history — to remain with his $95,000 annual salary. He told club management he felt he hadn’t played well enough to merit the raise, and rejected the offer, much to ownership’s astonishment. That contract appears in this auction, as well as the one for the 1972 season, when he finally agreed to the $100,000 salary only because “Mr. Fetzer [John, the owner of the Tigers] wanted me to have it,” as Kaline told The New York Times in December 1971.

“It’s part of his legend, if you will,” Mark says of his father’s decision to turn down the initial six-figure contract. “It’s part of who he was. … We didn’t live a lavish lifestyle, but baseball and the Tigers had provided him and his family with a comfortable life, and he was quite happy with how the Tigers were treating him. So I’m guessing that out of respect for all that the team had done for him, he turned down the deal.”

Mark was born in 1957, after his father was already a batting champion, a star, a city’s hero. He knew only that his father had “an unusual day job,” since back then most games were played in the sun. But he only had to look at the shelves stocked with awards to know that Dad was something special. He says with a laugh that “you could pick up a lot just by looking in the basement of our home.”

By the end of Al Kaline’s life, there were too many awards and photos and keepsakes to count; Mark says it was his father’s idea to auction much of his collection so it wouldn’t become a burden to his wife and their two sons. “His idea was to share it with the fans,” Mark says, with some of the auction’s proceeds going to Al’s favorite charities.

“He always believed that he was blessed to have a good life and a healthy family, so he gave a lot of his time to charities in and around Detroit, as well as the state of Michigan. He took me to a few of his many speaking engagements when I was a child, to give me the experience of seeing the other side of what he did. It was his way of reminding me what he always knew: You have to know how lucky you are.”

ROBERT WILONSKY is a staff writer at Intelligent Collector.

ROBERT WILONSKY is a staff writer at Intelligent Collector.