EPIC TWO-DAY EVENT INCLUDES A DECEMBER 1862 LETTER TO THE ARMY OF THE POTOMAC, AN AUTOGRAPHED CARTE DE VISITE, AN ICONIC PORTRAIT BUST AND MUCH MORE

By Robert Wilonsky

EVENT

LINCOLN AND HIS TIMES AMERICANA & POLITICAL SIGNATURE® AUCTION 6251

Feb. 12-13, 2022

Online: HA.com/6251a

INQUIRIES

Curtis Lindner

214.409.1352

CurtisL@HA.com

Beginning Feb. 12, the 213th anniversary of President Abraham Lincoln’s birth, Heritage Auctions will offer 530 documents and artifacts associated with The Great Emancipator, among them one of the most cited and significant letters of his presidency, written in the aftermath of the Battle of Fredericksburg. It has been decades since such a vaunted and valuable assemblage of Lincolnalia has been offered at auction, perhaps not since Oliver Barrett’s celebrated collection was sold in 1952.

“When my colleagues and I began discussing this auction last year,” says Curtis Lindner, Heritage Auctions’ Director of Americana, “we never realized the breadth and depth of the material that would be offered. We have held Lincoln-related auctions in the past, but this is far and above the best to date – an extraordinary event filled with historic achievements, none more so than the amendment abolishing slavery. Its offerings encompass the great man’s triumphs and tragedies.”

The two-day event, “Lincoln and His Times,” spans the course of Lincoln’s life and career, from his days of practicing law in Springfield, Ill., through his wartime presidency.

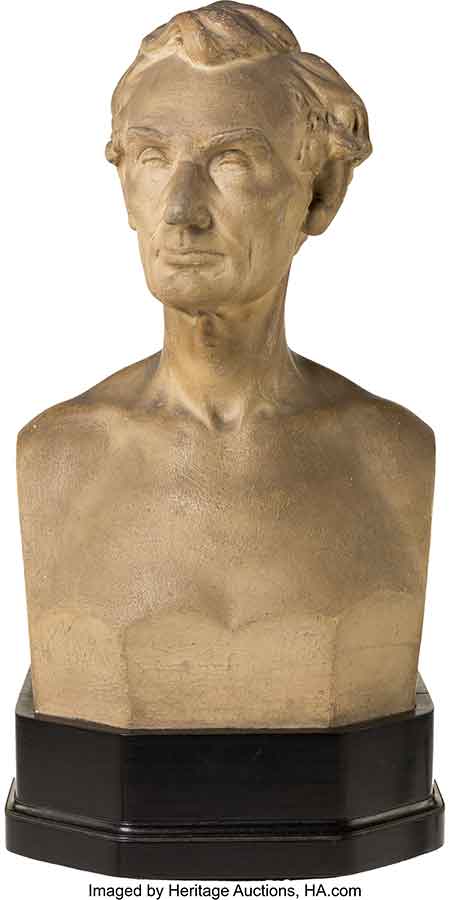

It includes an item likely to be considered among the most extraordinary – and historically significant – Lincoln artifacts ever to appear at auction: Lincoln’s personal copy of his portrait bust by Chicago artist Leonard Volk, made before Lincoln’s nomination as the Republican presidential candidate and presented to the Lincolns by Volk in May 1860. Upon their departure for Washington, D.C., the following year, the Lincolns gifted the portrait bust to the Rev. Noyes Miner, a Baptist minister who lived across the street from the Lincolns in Springfield and was “a friend very much beloved by my husband,” per a letter written by Mary Todd Lincoln in 1873.

With much fanfare, in 2019 the Miner family donated the 16th president’s Bible to the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum. But until now this bust has remained in the family’s possession; this is the first time it has appeared at auction.

“It has impeccable provenance,” Lindner says, “and is one of my favorite pieces in the auction.”

To eliminate the need for multiple sittings, Volk made a life mask of Lincoln – an early plaster copy of which, authenticated by the artist’s son, is also available in this auction. As The Metropolitan Museum of Art notes, “Volk’s portrait bust depicts Lincoln deep in thought and finds its greatest strength in the simple naturalism representing a vigorous man.” According to Volk himself, in the December 1881 issue of Century, Lincoln said that “in two or three days after Mr. Volk commenced my bust, there was the animal himself!”

There is much paper here, as well, among the plaster – “quiet paper that whispers its tender message,” as Carl Sandberg once wrote of Barrett’s assemblage, “or groaning, roaring paper that for those of imagination carries its own grief or elation of a vanished hour and day. Paper, if you please, sir or madam, as soundless as hushed footfalls on silent snow.”

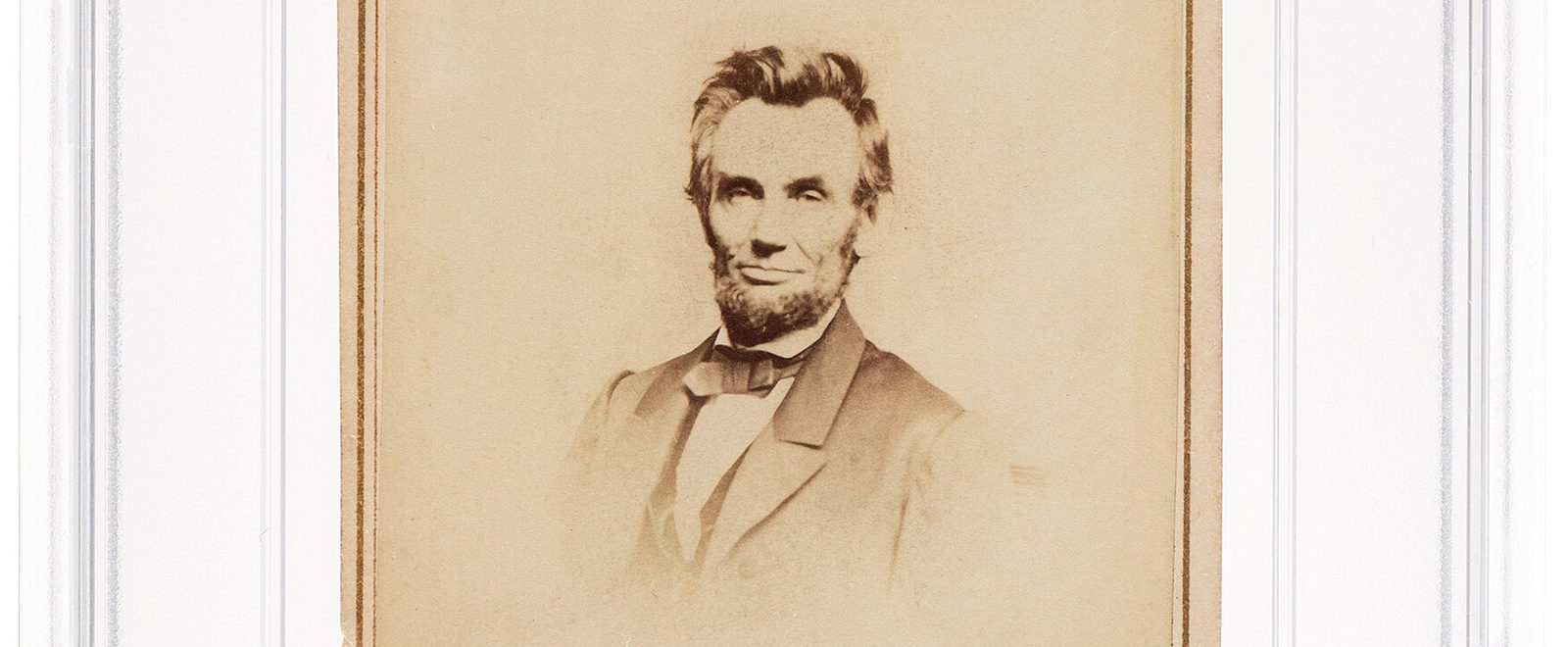

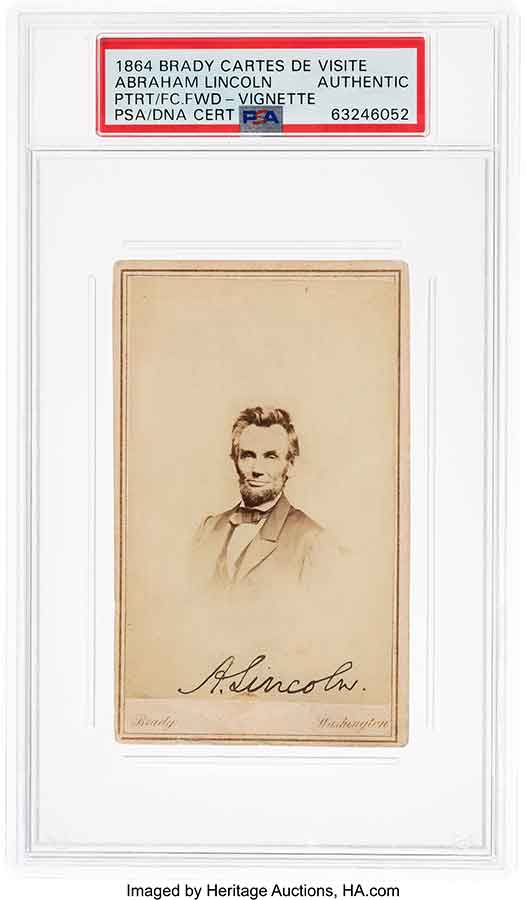

This auction counts among its offerings numerous rare and coveted items signed by Lincoln, among them a carte de visite taken by Mathew B. Brady in Washington, D.C., on Jan. 8, 1864, signed by the president. There are also numerous documents penned and signed by the president, including an oft-cited 1848 letter in which he supports then-Gen. Zachary Taylor’s candidacy for the presidency and another written two years later in which he explains a complex case to a client, reproduced in 1953’s The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln.

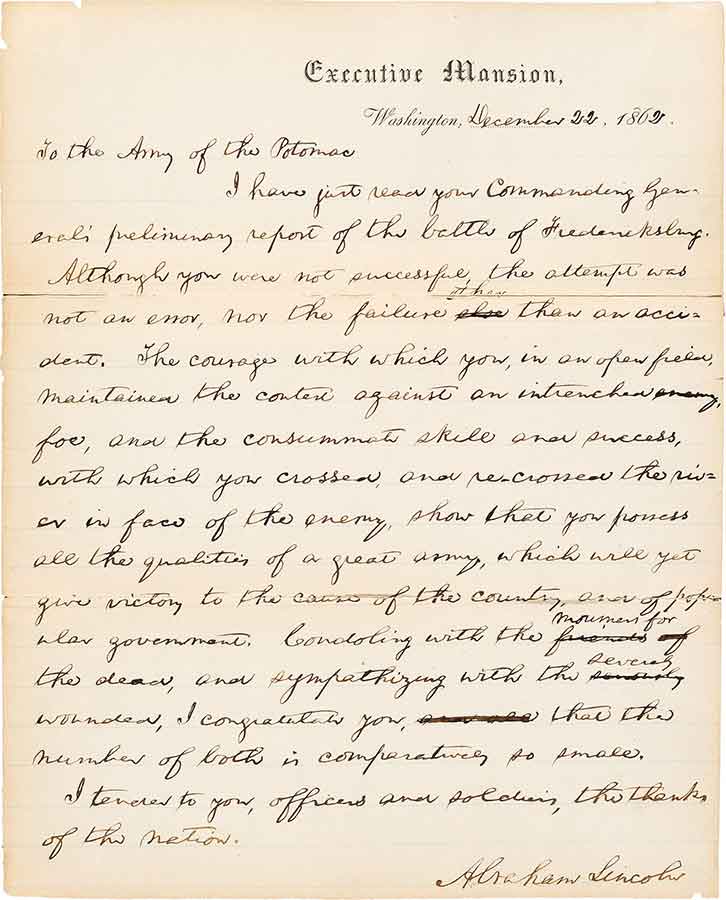

One such document featured in “Lincoln and His Times” is the oft-quoted Dec. 22, 1862, letter the president wrote to the Army of the Potomac following its demoralizing defeat at the Battle of Fredericksburg nine days earlier.

Under the command of Gen. Ambrose E. Burnside – and against the president’s own advice, as Doris Kearns Goodwin notes in Team of Rivals – Union forces numbering 122,000 marched across the Rappahannock to Fredericksburg. There, Confederate troops under the command of Gen. Robert E. Lee awaited on what the historian called the fortified high ground at Marye’s Heights.

“Caught in a trap,” Goodwin wrote, “the Union forces suffered 13,000 casualties, more than twice the Confederate losses, and were forced into humiliating defeat.”

So devastated was the president by the Union’s defeat at Fredericksburg, he is reported to have said, “If there is a worse place than hell, I am in it.” As Michael Burlingame wrote in his 1997 book The Inner World of Abraham Lincoln, a War Department secretary to whom he dictated several messages following the slaughter said later that “the calamity seemed to crush Lincoln. He looked pale, wan and haggard. He did not get over it for a long time and, that winter of 1863, he was downcast and depressed. He felt that the loss was his fault.”

Yet he summoned strength enough to issue a public letter of commendation to the troops, in the hopes of mitigating its impact and boosting morale. That letter, later turned into a broadside for mass distribution, has not appeared at auction for decades and is a centerpiece of this extraordinary event, as it spends precious few sentences speaking volumes about the man who wrote and signed the document.

“I have just read your Commanding General’s preliminary report of the battle of Fredericksburg,” Lincoln wrote. “Although you were not successful, the attempt was not an error, nor the failure other than an accident. The courage with which you, in an open field, maintained the contest against an entrenched foe, and the consummate skill and success with which you crossed and re-crossed the river, in face of the enemy, show that you possess all the qualities of a great army, which will yet give victory to the cause of the country and of popular government. Condoling with the mourners for the dead, and sympathizing with the severely wounded, I congratulate you that the number of both is comparatively so small.

“I tender to you, officers and soldiers, the thanks of the nation.”

In this auction, perhaps no piece of paper roared louder in the moment than this offering: an original draft manuscript petition of the Thirteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which abolished slavery in this country. This draft – signed by Schuyler Colfax, Speaker of the House of Representatives; Hannibal Hamlin, Vice President of the United States and President of the Senate; and 107 members of the 38th Congress – is likewise among the most significant documents Heritage Auctions has ever had the honor of offering.

“Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction,” reads this document’s text – the first time slavery had been explicitly mentioned in the Constitution, as Congress, directed by Lincoln, worked to eradicate it.

Offered here is one of the few surviving original duplicates of the joint resolution outlawing slavery. It has not been publicly available for more than a decade.

“Lincoln and His Times” also features myriad pieces that have never before been to auction, among them George Armstrong Custer’s gold-braided 7th Cavalry shoulder knots. According to a 1990 letter of provenance that accompanies the shoulder knots, from noted arms-and-armor authority Greg Martin, they came directly from Craig Custer, great-grandson of Neven Custer, George’s farm-tending brother. Wrote Martin, these shoulder knots are “one of the greatest pieces of historic Americana I have handled.”

In this auction, many pieces also come from Dr. Blaine Houmes, a collector of many categories of Lincolnalia with a focus on the president’s assassination.

Says Lindner, “My favorite pieces from his assemblage are tracings of Abraham Lincoln’s feet for a pair of his boots, and a rocking chair owned by Mary Todd Lincoln and used during her four-month stay at Bellevue Place Sanitarium in Batavia, Ill., in 1875. These two pieces should receive quite a bit of attention.”

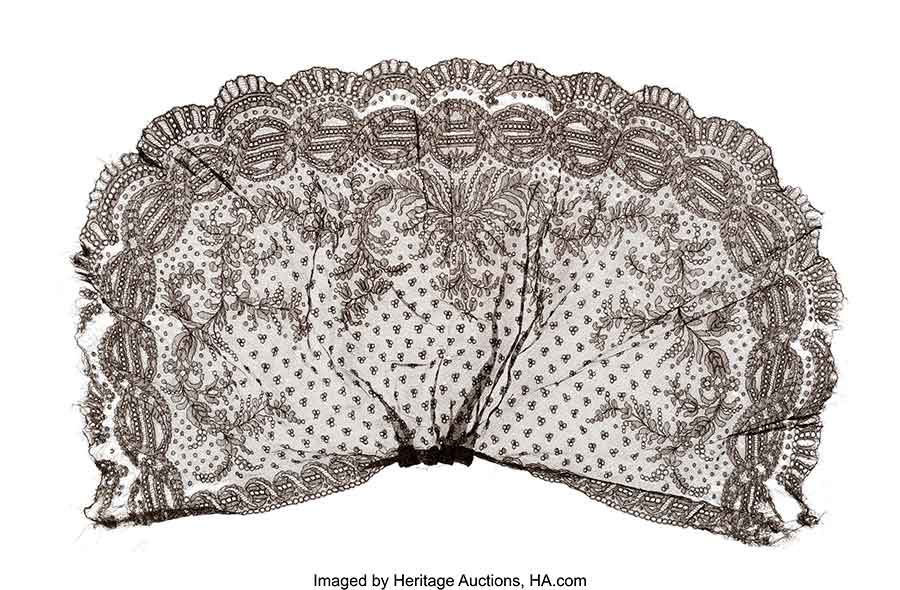

From Barrett’s historic sale comes another astonishing piece: Mary Lincoln’s black lace veil worn on the night John Wilkes Booth assassinated the president at Ford’s Theatre on April 14, 1865. Lincoln’s widow gifted the bonnet, among other items, to former slave Elizabeth Keckley, whose book Behind the Scenes: Or, Thirty Years a Slave, and Four Years in the White House has for decades provided Lincoln scholars invaluable insight into her relationship with Mary, first as seamstress, then as confidante and caretaker.

Upon her departure from D.C. in May 1865, Mary disbursed personal mementos belonging to her and her husband to friends and favorite staff members; to Keckley she gave the earrings, cloak and bonnet she had worn to Ford’s Theatre. Keckley kept them until 1890, when she sold them to Charles Gunther. The veil, which is remarkably well preserved considering its delicate nature and age, is accompanied by a simple signed note authenticating the heartbreaking keepsake.

Just as this auction documents Lincoln’s life, so, too, does it contain several significant items related to his death, including Booth’s riding crop from the assemblage of the late Dr. John Lattimer, the esteemed Columbia University urologist who was also a renowned collector of relics related to, among other subjects, Lincoln’s death. The black “swagger stick” with the gold-plated handle, which the assassin can be seen posing with in numerous photos featured in Richard and Kellie Gutman’s 1979 book John Wilkes Booth Himself, was gifted to Booth by Neal Bryant, who, along with his two brothers, ran a minstrel show on Broadway from 1857 to 1867. The men were good friends with Booth, as evidenced by the engraving: “Neal Bryant to J. W. Booth.”

But perhaps no item linked to the assassination is more sought-after than the $100,000 reward broadside issued by the U.S. War Department on April 20, 1865, for information concerning the whereabouts of “THE MURDERER” Booth and confederates John H. Surratt (misspelled “Surrat”) and David C. Herold (misspelled “Harold”). This poster from what has been deemed the most important manhunt in American history is but one of a handful of known to exist. So coveted and significant is this item that another sold at Heritage Auctions in September for a record $275,000, breaking the previous auction record for a Booth broadside set earlier in 2021.

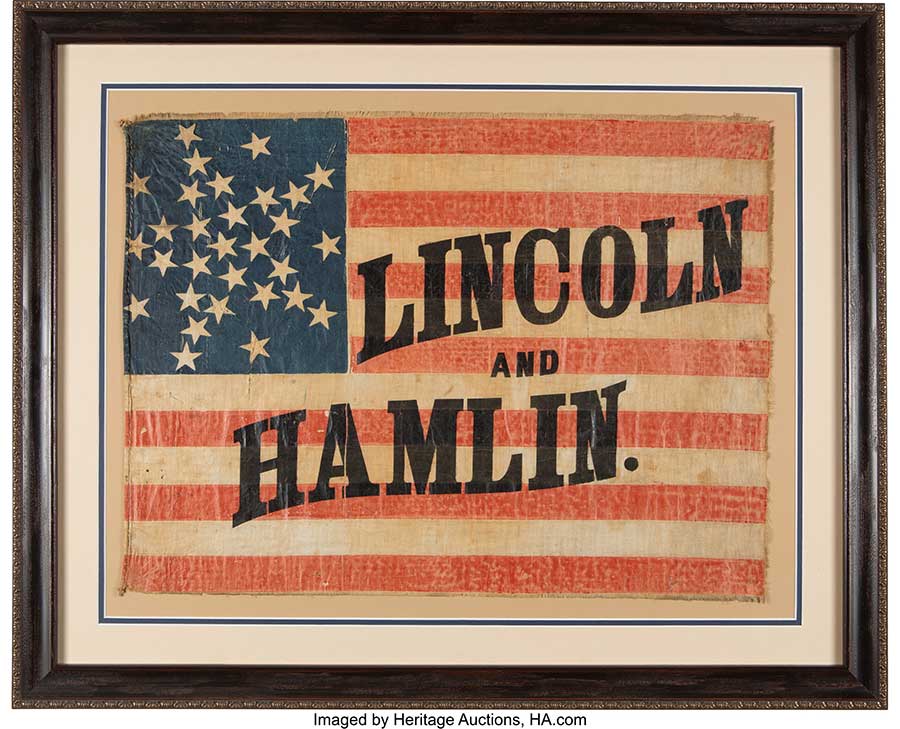

Of course this auction is filled with far happier moments and memories, too, including coveted platters and plates from the Lincoln White House, as well as two flags from his 1860 presidential campaign, among them this offering that misspells his name as “Abram.” But this oversized flag is a centerpiece of the auction, as it comes directly from the family of its original owner, Samuel Park, who carried it during an 1860 Ohio torchlight parade supporting Lincoln and running mate Hannibal Hamlin.

And here is something as profound as it is pretty: a custom pocket knife, in its original presentation box, gifted to Lincoln for attending the Great Central Sanitary Fair in Philadelphia on June 16, 1864 – his final appearance at the event during which money was raised to aid wounded Union soldiers. Alone, the knife and box constitute a breathtaking keepsake.

The elegant blades (one engraved “Liberty, July 4th 1776. Abraham Lincoln, Jany. 1st, EQUALITY. 1864”), scissors and file are encased in white mother-of-pearl with a small inlaid gold plaque engraved “ABRAHAM LINCOLN.” It has been kept in its custom-fitted hinged oak box with a plush-lined, satin lid interior that reads: “THIS BOX Is made from the Wood and Iron, formerly Supporting the ‘OLD LIBERTY BELL,’ Now in Independence Hall, Philadelphia, And Presented to the Great Central Fair, in aid of the U.S. Sanitary Commission, June, 1864, by A. B. Justice.”

But these two items are accompanied by something just as remarkable: a thank-you note from the Executive Mansion, which, like many of the documents in this event, was later published in The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln.

In the letter, Lincoln wrote that he “received at the hands of Wm. D. Kelley, a very beautiful and ingeniously constructed Pocket Knife, accompanied by your kind letter of presentation. The gift is gratefully accepted and will be highly valued, not only as an extremely creditable specimen of American workmanship, but as a manifestation of your regard and esteem which I most cordially appreciate.”

And he signed it, “Your Ob’t serv’t, A. Lincoln.”

“What I love most about this piece is actually being able to hold something President Lincoln himself once had in his hands,” Lindner says. “That gets to the very thrill of this entire event: the ability to possess something seen only in photographs or read about in the numerous rich histories of Abraham Lincoln. This is why we’re so honored to present ‘Lincoln and His Times.’ It brings so many historic yesterdays into the present and lets collectors share them for countless tomorrows.”

ROBERT WILONSKY is a staff writer at Intelligent Collector.

ROBERT WILONSKY is a staff writer at Intelligent Collector.